[Herbert] Hoover wants to be president. It fits his self-image as a benevolent engineer-king destined to save the populace from the vagaries of politics. The people want Hoover to be president; he’s a super-double-war-hero during a time when most other leaders have embarrassed themselves. Even politicians are up for Hoover being president; Woodrow Wilson has just died, leaving both Democrats and Republicans leaderless. The situation seems perfect.

Hoover bungles it. He plays hard-to-get by pretending he doesn’t want the Presidency, but potential supporters interpret this as him just literally not wanting the Presidency. He refuses to identify as either a Democrat or Republican, intending to make a gesture of above-the-fray non-partisanship, but this prevents either party from rallying around him. Also, he might be the worst public speaker in the history of politics.

Warren D. Harding, a nondescript Senator from Ohio, wins the Republican nomination and the Presidency. Hoover follows his usual strategy of playing hard-to-get by proclaiming he doesn’t want any Cabinet positions. This time it works, but not well: Harding offers him Secretary of Commerce, widely considered a powerless “dud” position. Hoover accepts.

Harding is famous for promising “return to normalcy”, in particular a winding down of the massive expansion of government that marked WWI and the Wilson Administration. Hoover had a better idea – use the newly-muscular government to centralize and rationalize American In his first few years in Commerce – hitherto a meaningless portfolio for people who wanted to say vaguely pro-prosperity things and then go off and play golf – Hoover instituted/invented housing standards, traffic safety standards, industrial standards, zoning standards, standardized electrical sockets, standardized screws, standardized bricks, standardized boards, and standardized hundreds of other things. He founded the FAA to standardize air traffic, and the FCC to standardize communications. In order to learn how his standards were affecting the economy, he founded the NBER to standardize government statistics.

But that isn’t enough! He mediates a conflict between states over water rights to the Colorado River, even though that would normally be a Department of the Interior job. He solves railroad strikes, over the protests of the Department of Labor. “Much to the annoyance of the State Department, Hoover fielded his own foreign service.” He proposes to transfer 16 agencies from other Cabinet departments to the Department of Commerce, and when other Secretaries shot him down, he does all their jobs anyway. The press dub him “Secretary of Commerce and Undersecretary Of Everything Else”.

Hoover’s greatest political test comes when the market crashes in the Panic of 1921. The federal government has previously ignored these financial panics. Pre-Wilson, it was small and limited to its constitutional duties – plus nobody knows how to solve a financial panic anyway. Hoover jumps into action, calling a conference of top economists and moving forward large spending projects. More important, he is one of the first government officials to realize that financial panics have a psychological aspect, so he immediately puts out lots of press releases saying that economists agree everything is fine and the panic is definitely over. He takes the opportunity to write letters saying that Herbert Hoover has solved the financial panic and is a great guy, then sign President Harding’s name to them. Whether or not Hoover deserves credit, the panic is short and mild, and his reputation grows.

While everyone else obsesses over his recession-busting, Hoover’s own pet project is saving the Soviet Union. Several years of civil war, communism, and crop failure have produced mass famine. Most of the world refuses to help, angry that the USSR is refusing to pay Czarist Russia’s debts and also pretty peeved over the whole Communism thing. Hoover finds $20 million to spend on food aid for Russia, over everyone else’s objection […]

So passed the early 1920s. Warren Harding died of a stroke, and was succeeded by Vice-President “Silent Cal” Coolidge, a man famous for having no opinions and never talking. Coolidge won re-election easily in 1924. Hoover continued shepherding the economy (average incomes will rise 30% over his eight years in Commerce), but also works on promoting Hooverism, his political philosophy. It has grown from just “benevolent engineers oversee everything” to something kind of like a precursor modern neoliberalism:

Hoover’s plan amounted to a complete refit of America’s single gigantic plant, and a radical shift in Washington’s economic priorities. Newsmen were fascinated by is talk of a “third alternative” between “the unrestrained capitalism of Adam Smith” and the new strain of socialism rooting in Europe. Laissez-faire was finished, Hoover declared, pointing to antitrust laws and the growth of public utilities as evidence. Socialism, on the other hand, was a dead end, providing no stimulus to individual initiative, the engine of progress. The new Commerce Department was seeking what one reporter summarized as a balance between fairly intelligent business and intelligently fair government. If that were achieved, said Hoover, “we should have given a priceless gift to the twentieth century.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

December 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover in the Harding and Coolidge years

December 5, 2024

Ontario’s housing market squeezed by the 35.6% combined tax rate on new builds

The housing situation in Toronto and the rest of the province has been very tight for years. Lots of would-be buyers chasing the proportionally smaller number of new houses being built. This drives prices higher, but no matter how much of the final price is the builder’s profit margin, the government gets nearly four times as much on every new house sale:

The National Post previously reported that at least a third of a new home’s sticker price in Ontario was comprised of taxes, but an updated report, courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis (CANCEA), now puts the figure at 35.6 per cent.

(It gets even better when it comes to affordable housing — but more on that later.)

The Increasing Tax Burden on New Ontario Homes: 2024, which was commissioned by the Residential Construction Council of Ontario and released by CANCEA on Tuesday, is eye-opening for reasons beyond the fact that a compendium of largely superfluous taxes and production levies has reached 35.1 per cent of the final purchase price of a new home in the city of Toronto. It’s 35.5 per cent in the outlying 905 region, and 34.5 per cent in Ottawa.

The report needed only 16 pages to elucidate how bureaucratic machinations aren’t just gouging prospective homebuyers, but homeowners, too — especially the estimated 1.2 million whose mortgages, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, are due for renewal in 2025.

Read closely enough, CANCEA’s report makes a strong argument that, effectively, Canadians work for the government rather the other way around.

For example, CANCEA’s report demonstrates that 70 per cent of aforesaid taxes on new homes “consist of direct fees on the home, such as DC (development charges) and other fees”.

“For homes priced at $450,000,” which aligns with median income, “… the tax burden rises sharply to 45.2 per cent,” says the report, which also notes that economics often force developers to build smaller units that are insufficient for families.

November 29, 2024

QotD: Why nothing gets done in the Current Year

… we do gain a lovely illustration of why nothing ever really gets done in this modern world. Sure, the politicians have demanded more [advanced logic] chips in a country that doesn’t have any spare chip technicians — TSMC has had to import their own from Taiwan — and so on and so on. But there’s also this:

Having pumped billions of dollars into building the next generation of computer chip factories in the US, the Biden administration is facing new pressure over the health and safety risks those facilities could pose. Environmental reviews for the new projects need to be more thorough, advocates say. They lack transparency around what kinds of toxic substances factory workers might handle, and plans to keep hazardous waste like forever chemicals from leaching into the environment have been vague.

A coalition of influential labor unions and environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, have since submitted comments to the Department of Commerce on draft environmental assessments, saying that the assessments fall short. The coalition’s comments flag lists of potential issues at several projects in Arizona and Idaho, including how opaque the safety measures that manufacturers will take to protect both workers and nearby residents are.

This is not a serious complaint. This is actually the national association of environmental studies writers spotting a gravy train passing by and desiring to dip their ladle in. And that’s all it is too. But it’s also that excellent example of why fuck all ever gets built. We’ve an entire — and politically powerful — class that makes their living producing the hundred tonne reports that accompany building anything. And they’re not going to allow anything to be built unless they get paid for writing hundred tonne reports. And, to complete the circle, if every activity requires a hundred tonne report then fuck all will ever get done.

There was, back a time, a law passed about blood minerals. The law said anyone who might use them must write to all suppliers to ask if they do. Then those said anyones must tell consumers whether they do. This cost $4 billion just in the first year. From what I’ve heard — and might take the trouble to prove one day — the bloke who led the campaign for the law requiring the letters now runs a very profitable consultancy advising large corporates on how to write the letters. $4 billion spent by society so that one bloke can gain a minor summer place in the Hamptons. This doesn’t make us richer as a whole, it’s pissing the wealth of the nation up the wall.

Carthage, it’s the only solution. The biggest problem who is who the hell would buy our nice new stock of enslaved environmental bureaucrats? Razing, salt, ploughs, these are easy but who’s mad enough to offer a positive price for the last part of the process?

Tim Worstall, “Why Fuck All Ever Gets Done In This Modern World”, It’s all obvious or trivial except …, 2024-08-28.

November 24, 2024

QotD: Wood

If someone today invented wood, it would never be approved as a building material. It burns, it rots, it has different strength properties depending on its orientation, no two pieces are alike, and most cruelly of all, it expands and contracts based on the relative humidity around it. However, despite all of these problems, wood is the material of choice when building houses. In fact, we can use wood better than we can use steel, masonry and concrete.

Joseph Lstiburek, Builder’s Guide to Cold Climates, 2000.

November 8, 2024

“The Science™, that thing we’re supposed to believe in and obey – is distinctly and increasingly political”

President-elect Donald Trump has a vast array of options to tackle in the traditional first hundred days of his administration. Chris Bray says that one of the very first of these should be the depoliticization of the federal science agencies:

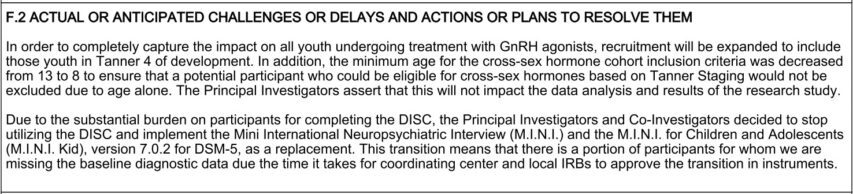

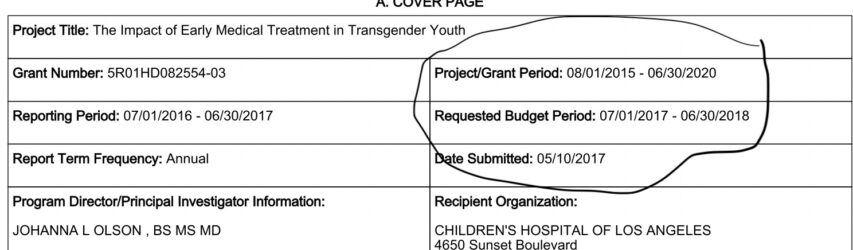

Donald Trump has spoken very clearly about his day-one determination to end the mutilation of children in the service of gender ideology, but let’s look for the roots of that poison tree. Via Billboard Chris, here’s a sample descriptive section from a National Institutes of Health grant given to a pediatric gender physician in Los Angeles, and read this carefully to find the most important sentence:

Dr. Johanna Olson-Kennedy has worked to push gender hormone treatment down to eight year-olds, with research funding from the federal government. Now, big finish: the dates on the NIH grant that Billboard Chris highlighted:

This is a project — gender hormones for eight year-olds — that operated with federal funding during the first Trump administration. Policy expressed in words meets policy expressed in cash. This is what matters, year after year, through Republican and Democratic administrations alike (click to enlarge):

The money, the money, and the money. What you fund is what you’re doing. It may not seem like a big target, but the politicization of federal science funding is a root cause of institutional decay and pathological narrative-making, and cutting the money pipeline to politicized science is the policy action that will matter for decades. Remaking the funding pipeline for federal science grants is a day one priority, because the money will shape policy far more than any declaration of intent.

The problem is everywhere: the NIH, the NSF, NASA, NOAA, and so on. SpaceX is catching rockets; NASA is funding this: “21-EEJ21-0020 ASSESSMENT OF THE GULF COAST ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE LANDSCAPE FOR EQUITY.”

And this: “EXPLORING SYNERGISTIC OPPORTUNITIES BETWEEN CHARLOTTE-AREA ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE INITIATIVES AND NASA EARTH SCIENCE INFORMATION.”

Pick a federal science grant website and spend some time exploring it. Here’s the National Science Foundation’s funding opportunities page. Sample grant program: “Growing Research Compliance Support and Service Infrastructure for Nationally Transformative Equity and Diversity”.

Today’s funded program for transformative science equity and environmental justice is tomorrow’s new policy measures. This is the pipeline to programs. What you fund today is what you’re going to do in five years.

The McDonald’s ice cream machines are always broken because of bad IP laws

Even if you never to to a McDonald’s yourself, you’ve undoubtedly heard that the ice cream machines are always broken. I hadn’t really given it any thought — it’s been years since I visited one of the restaurants and I don’t eat much ice cream — but Peter Jacobsen explains the weird and infuriating reason for the phenomenon:

How could it be that the ice cream machines at McDonald’s are so consistently broken? It turns out that, until just recently, it was illegal to hire most people to fix them. To understand why, we’re going to have to take a detour into the world of intellectual property.

DMCA Woes

So why has it been illegal for McDonald’s to hire people to fix their ice cream machines? Well, that’s where the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) comes in. If you’re familiar with the DMCA, this is probably confusing to you.

Generally the DMCA is a big concern on content creation platforms like YouTube. If someone uses copyrighted music, he or she gets DMCAed. This is slang for when a video gets its monetization redirected to the owner of whatever copyrighted content was used.

DMCA takedowns draw a lot of ire, because the law is clumsily applied and often even legitimate uses of copyrighted content (e.g., fair use) are punished.

But the DMCA extends beyond content creation, as chronicled by Elizabeth Chamberlain of iFixit, an organization dedicated to ensuring that product owners have the right and ability to fix their property. Many machines ranging from phones to ice cream machines utilize copyrighted software to function. Sometimes, this software limits product users more than they’d like.

For example, iPhone software locks users into particular user interfaces. If a user wants to customize past some point, he’s going to have to modify the software more than the company intends. This process, called jailbreaking, involves breaking through “digital locks”. The DMCA often interprets breaking these locks as a violation of the intellectual property of the copyright holder.

The problem gets even worse when you recognize that fixing things — say, McDonald’s ice cream machines — means breaking past those digital locks. This means anyone hired to repair the machine would need an official blessing from the manufacturer.

However, things have changed. As of October 18th, the opening of digital locks for “retail-level commercial food preparation equipment” is now exempt from this DMCA rule. McDonald’s will now be able to hire from a larger group of people to fix their ice cream machines.

DMCA has allowed a lot of intellectual property owners to collect unearned rents while neglecting the needs of the customers who’ve bought, leased, or rented things that incorporate their IP.

Note, this is only an exemption to the rule. The rule itself has not changed. Second, other regulations still hamper McDonald’s franchise owners from fixing their own machines. As Chamberlain points out:

While it’s now legal to circumvent the digital locks on these machines, the ruling does not allow us to share or distribute the tools necessary to do so. This is a major limitation … few will be able to walk through it without significant difficulty.

It is still a crime for iFixit to sell a tool to fix ice cream machines, and that’s a real shame … Without these tools, this exemption is largely theoretical for many small businesses that don’t have in-house repair experts.

So your chance of getting a McFlurry has improved, but you can’t quite celebrate a total win yet.

The battle against these DMCA laws isn’t limited to ice cream machines. The “right to repair” movement spearheaded by organizations including iFixit has already battled for exemptions for medical devices, consumer devices like phones and tablets, vehicles, and assistive technologies for people with disabilities.

November 5, 2024

October 24, 2024

It’s called “piercing the corporate veil” and it’s a terrible idea

Tim Worstall explains why the EU’s latest brain fart is not just a bad idea in its own right, but a truly horrific precedent for the future:

… But now, this, now this is even more important than that. We can deal with free speech by the judicious use of lampposts. This is worse:

The European Union has warned X that it may calculate fines against the social-media platform by including revenue from Elon Musk’s other businesses, including Space Exploration Technologies Corp. and Neuralink Corp., an approach that would significantly increase the potential penalties for violating content moderation rules.

Under the EU’s Digital Services Act, the bloc can slap online platforms with fines of as much as 6% of their yearly global revenue for failing to tackle illegal content and disinformation or follow transparency rules.

In English law that’s known as “piercing the corporate veil”. It’s also something we don’t do. Because that corporate veil is the very thing, the only thing, that makes large scale economic activity possible.

It has actually been said — and not just by me — that the invention of the limited company is the third grand invention of all time. Agriculture, the scientific method, the limited company.

Before the limited co everything was done through partnerships. Every individual involved in the ownership of something was liable for all of the debts of that thing. Which, when you’ve got 5 or 10 blokes trading isn’t that bad an incentive upon them to be honest.

Now think of large scale activity. We want a blast furnace — plenty of folk say Britain should have one after all. £3 to £5 billion these days. OK. No one’s got that much. So, we need to mobilise the savings of many thousands of people to go build it. But without limited liability that means all of those thousands are liable for all the debts — off into the future — of that blast furnace.

“Invest £500 in the new, new British Steel. And if we fuck up then in 10 years’ time they’ll come and take your house.”

Err, yes.

Large scale economic activity depends upon being able to separate the debts of one specific activity from the general economic life of all its backers. If this is not true then no one will invest in large scale economic activity. Therefore we won’t have large scale economic activity. Which would, you know, be bad.

September 29, 2024

Fleeced: Canadians Versus Their Banks by Andrew Spence

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte talks about one of Sutherland House’s most recent publications:

I could write about eight versions of this post based on the many revelations in Andrew Spence’s Fleeced: Canadians Versus Their Banks, the latest edition of Sutherland Quarterly, released this week. I’m going to run with the version most relevant to my fellow publishers and small business people in Canada.

Andrew lays out in aggravating detail how Canadian banks, although chartered by the federal government to facilitate economic activity in the broader economy, do all they can to avoid lending to small and medium businesses, never mind that small and medium businesses employ two-thirds of our private-sector labour force and account for half of Canada’s gross domestic product.

By OECD standards, small businesses in Canada are starved of bank credit, and when they are able to secure a loan, they pay through the nose. The spread between interest rates on loans to small businesses and large businesses in Canada is a whopping 2.48 percent, compared to .42 percent in the US—more than five times higher.

Why? Because Canada’s banks are a tight little oligopoly, impervious to meaningful competition. Their cozy situation allows them to be exceedingly greedy. Their profits and returns to shareholders are wildly beyond those of banks in the US and UK (and, as Andrew demonstrates, their returns from their Canadian operations are far in excess of those from the US market, meaning they screw the home market hardest.)

Our banks never miss an opportunity to impose a new fee, or off-load risk. From their perspective, small business involves too much risk — some of them will inevitably fail. The banks prefer that publishers and dry-cleaners and restaurateurs either finance themselves by pledging their homes, or use their credit cards to cover fluctuations in cash flow or make investments that will help them hire, expand, and grow. And that’s what entrepreneurs do. According to a survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, only one in five respondents accessed a bank loan or line of credit. Half of respondents financed themselves, tapped existing equity and personal lines of credit, and about 30 percent used their high-interest credit cards.

(The banks, incidentally, claim they need to keep credit card rates around 20 percent because their clients are high credit risks when their own data shows the risk is minimal. They simply prefer to gouge customers. To a banker, forcing hundreds of thousands of small businesses to use their credit cards to finance their businesses rather than giving them proper small business loans at reasonable rates is great business.)

By severely rationing credit and making it exceedingly expensive, Canada’s banks siphon off an ungodly share of entrepreneurial profit to themselves while leaving the entrepreneur with all the risk. Their insistence on putting their own profits above service to the Canadian economy is one of the main reasons Canada has such a slow-growing, unproductive economy and a stagnant standard of living.

There is much else in this slim volume to make your blood boil: exorbitant fees on chequing and savings accounts; mutual fund expenses that torpedo investments; ridiculous mortgage restrictions, infuriating customer service …

The “Foundations” essay could apply equally to Canada’s doldrums as it does to Britain

Earlier this week, I linked to the “Foundations” essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman and it struck me that so much of what they discuss about Britain’s stagnation applied at least as well to Canada. In the National Post, John Ivison concurs:

The “Foundations” essay pointed to moribund GDP per capita growth, among other data points, to make the argument that Britain is standing still economically. (Britain’s economy grew 0.7 per cent a year between 2002 and 2022, Canada’s increased 0.6 per cent a year in the same period, while U.S. output swelled 1.16 per cent a year.)

In relative terms, both countries are getting poorer: in 2002, Canada’s GDP per person was 81 per cent of the U.S.; in 2022, it was 72 per cent. The same figures for the U.K. against the U.S. are 78 per cent in 2002 and, 70 per cent in 2022.

The reason for Britain’s stagnation, the authors argue, is that it has effectively banned investment in transportation, energy and housing — “the foundations it needs to grow.”

Sound familiar?

“The most important economic fact about modern Britain is that it is difficult to build almost anything, anywhere. This prevents investment, increases energy costs and makes it harder for productive economic clusters to expand,” the authors write, saying the result is lower productivity, incomes and tax revenues.

They argued that Britain needs a program of reform with the scale and ambition of the liberalization of the 1980s that focused on cutting taxes, curbing union power and privatizing state-run industries.

“This time we must focus on making it easier to invest in homes, labs, railways, roads, bridges, interconnectors and nuclear reactors,” they write.

That’s a difficult proposition for politicians who are able to resist anything except the temptation to use resources for immediate electoral gratification, rather than investing for a time after they have left office.

Both Canada and Britain are laggards when it comes to investment in infrastructure. While China spent more than five per cent of its GDP on roads, bridges and other infrastructure in 2021, Canada invested just 0.5 per cent (down from 1.3 per cent in 2010) and the U.K. 0.9 per cent.

But the lack of dynamism is not simply political expediency. Rather, it is motivated by an indifference, even a hostility, toward building critical infrastructure.

The Foundations report noted that Britain has not built a reservoir for 30 years, yet faces chronic water shortages in the east of England. Its environmental agency has blocked new development on the basis that it could only be supplied with water by draining environmentally valuable chalk streams. The result is that England’s innovation hub, Cambridge, is barred from expanding, which threatens to strangle the country’s life-sciences industry.

Similar impulses are at work in Canada. Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said in February that Ottawa would stop investing in new road infrastructure — a position he later clarified to say meant the federal government would not fund large projects like a highway tunnel connecting Quebec City and Levis, Que.

That same sentiment is reflected in the federal Liberal government’s Impact Assessment Act, passed in 2019, which slowed the pace and increased the cost of major project approvals.

On the housing front, a generation of activists emerged who were intent on preventing urban sprawl yet were also opposed to building mid-rise buildings of the kind that eased housing pressures in continental Europe. Constraints on approval are a major contributor to the 3.5-million-unit housing gap because supply has not kept pace with demand.

The consequence of Canada’s regulatory sclerosis is what business veteran Paul Deegan and former clerk of the Privy Council Kevin Lynch in an FP Comment article earlier this year referred to as “an insidious stealth tax on Canadian jobs and growth“.

Taking each of the “foundations” in turn, the depth of the problem becomes clearer — but so do the solutions.

This Bridge Should Have Been Closed Years Before It Collapsed

Practical Engineering

Published Jun 18, 2024Why Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed.

This is a crazy case study of how common sense can fall through the cracks of strained budgets and rigid oversight from federal, state, and city staff. And the lessons that came out of it aren’t just relevant to people who work on bridges. It’s a story of how numerous small mistakes by individuals can collectively lead to a tragedy.

(more…)

September 26, 2024

Glimmers of hope for lower taxes on US taxpayers

J.D. Tuccille welcomes the discussion among the Presidential candidates about lowering the taxes Americans have to pay, and points out that the economic distortions of the current tax code (including “temporary” measures introduced during WW2) make everyone less well-off:

Three months after proposing to end federal taxing of tips — an idea promptly confiscated without compensation by Kamala Harris’s campaign — Donald Trump doubled down by saying “we will end all taxes on overtime” if he’s elected president. Without a doubt, millions of Americans who resent government’s ravenous bite out of their paychecks immediately began contemplating just how much of their income they could shield from the tax man that way.

Tips and Overtime for Everybody!

“Can someone get paid in primarily tips and overtime?” quipped the Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome. “Asking for a few million friends.”

On a more serious note, the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Sean Higgins thought exempting overtime pay “wouldn’t necessarily be a bad idea … but, overall, it is not likely to make that much of a difference to most workers because overtime isn’t that common”. He’d been more strongly supportive of exempting tips because that “would put more money directly in the pockets of working Americans without either costing employers more or raising prices for customers”. He also liked that freeing tips from taxation would “keep tipping out of the reach of the regulatory state”.

But what if overtime pay becomes more common precisely because it’s not taxed?

The people at the Tax Foundation expect that’s exactly what will happen, just as Lincicome joked. Thinking through the implications of exempting overtime pay from taxation, Garrett Watson and Erica York warned that “exempting overtime pay from income tax would significantly distort labor market decisions. Employees would be encouraged to take more overtime work, and hourly or salaried non-exempt jobs may become more attractive if the benefit is not extended to salaried employees who are exempt from Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) overtime rules.”

The Tax Foundation’s Alex Muresianu had a similar reaction to the proposals to exempt tips from taxes from both Trump and Harris. He thinks “the proposal would make more employees and businesses interested in moving from full wages to a tip-based payment approach”. He foresaw “substantial behavioral responses, such as previously untipped occupations introducing tipping”.

Of course, a world in which more Americans receive their pay beyond the reach of the tax man is a welcome prospect to many of us. If politicians want to phase out income taxes, even unintentionally, who are we to complain? Hang on a minute while I set up my virtual tip jar. In fact, there’s precedent for government policy around wages to cause major unintended consequences. Take, for example, employer-provided healthcare coverage.

Government Policy Has Distorted Compensation Before

“One of the most important spurs to growth of employment-based health benefits was — like many other innovations — an unintended outgrowth of actions taken for other reasons during World War II,” according to the 1993 book, Employment and Health Benefits: A Connection at Risk. “In 1943 the War Labor Board, which had one year earlier introduced wage and price controls, ruled that contributions to insurance and pension funds did not count as wages. In a war economy with labor shortages, employer contributions for employee health benefits became a means of maneuvering around wage controls. By the end of the war, health coverage had tripled.”

Given that health benefits became a substitute form of compensation to escape a wage freeze, it’s not difficult to imagine the United States moving toward a situation in which a lot more people receive the bulk of their pay from untaxed tips and overtime pay.

September 24, 2024

British stagnation – “at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”

Ed West reviews a new essay by Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes, and Sam Bowman which tries to identify the underlying reasons for British economic stagnation:

The theme running through the essay is that the British system makes it very hard to invest and extremely expensive and legally difficult to build, making housing and energy costs prohibitive.

While we all know we have fallen in status, “most popular explanations for this are misguided. The Labour manifesto blamed slow British growth on a lack of “strategy” from the Government, by which it means not enough targeted investment winner picking, and too much inequality. Some economists say that the UK’s economic model of private capital ownership is flawed, and that limits on state capital expenditure are the fundamental problem. They also point to more state spending as the solution, but ignore that this investment would face the same barriers and high costs that existing infrastructure projects face, and that deters private investment.”

The problem is that “all of these explanations take the biggest obstacles to growth for granted: at some point it becomes impossible to grow when investment is banned”.

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the industrial price of energy had tripled in under 20 years. Per capita electricity generation in Britain is only two-thirds that of France, and a third of the US, making us closer to developing countries like Brazil and South Africa than other G7 states. Transport projects are absurdly expensive, mired by planning rules, and all of this helps explain why annual real wages for the median full-time worker are 6.9 per cent lower than in 2008.

In one of the most notorious examples, the authors note that “the planning documentation for the Lower Thames Crossing, a proposed tunnel under the Thames connecting Kent and Essex, runs to 360,000 pages, and the application process alone has cost £297 million. That is more than twice as much as it cost in Norway to actually build the longest road tunnel in the world.”

Britain’s political elites have failed, they argue, because they do not understand the problems, so “they tinker ineffectually, mesmerised by the uncomprehended disaster rising up before them”.

Even “before the pandemic, Americans were 34 percent richer than us in terms of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, and 17 percent more productive per hour … The gap has only widened since then: productivity growth between 2019 and 2023 was 7.6 percent in the United States, and 1.5 percent in Britain … the French and Germans are 15 percent and 18 percent more productive than us respectively.” The gap continues to widen, and on current trends, Poland will be richer than the United Kingdom by the end of the decade.

Britain began to fall behind after the War, but after decades of relative stagnation, its GDP per capita had converged with the US, Germany and France in the 1980s, and our relative wealth peaked in the early Blair years. (Personally, I wonder if one reason for the great Oasis nostalgia is simply that we were rich back then.) If Britain had continued growing in line with its 1979-2008 trends, average income today would be £41,800 instead of £33,500 — a huge difference.

France is the most natural comparison point to Britain, a country “notoriously heavily regulated and dominated by labour unions”. This is sometimes comical to British sensibilities, so that “French workers have been known to strike by kidnapping their chief executives – a practice that the public there reportedly supports – and strikes are so common that French unions have designed special barbecues that fit in tram tracks so they can grill sausages while they march.” Only in France.

It is also heavily taxed, especially in the realm of employment, and yet despite this, French workers are significantly more productive. The reason is that France “does a good job building the things that Britain blocks: housing, infrastructure and energy supply”.

With a slightly smaller population, France has 37 million homes compared to our 30 million. “Those homes are newer, and are more concentrated in the places people want to live: its prosperous cities and holiday regions. The overall geographic extent of Paris’s metropolitan area roughly tripled between 1945 and today, whereas London’s has grown only a few percent.” One quality-of-life indicator is that “800,000 British families have second homes compared to 3.4 million French families“.

They also do transport far better, with 29 tram networks compared to seven in Britain, and six underground metro systems against our three. “Since 1980, France has opened 1,740 miles of high speed rail, compared to just 67 miles in Britain. France has nearly 12,000 kilometres of motorways versus around 4,000 kilometres here … In the last 25 years alone, the French built more miles of motorway than the entire UK motorway network. They are even allowed to drive around 10 miles per hour faster on them.”

September 2, 2024

There’s no limit to how progressive politicians want to control your life

In the National Post a couple of days ago, Carson Jerema provided many examples of how the Canadian federal government — despite failing and fumbling so many of its existing responsibilities — still wants to increase control over the daily lives of Canadians:

After a decade or so, progressives are on the defensive in Canada and elsewhere because regular people, as in those who are not activist weirdos, are tired of the agenda to control every aspect of our lives. Point this out to a progressive, and they will deny that anyone’s life is being interfered with and claim only some far-right monster would think otherwise. They can’t believe there are people out there who share a different view. They don’t understand how this could be.

But progressive governments are trying to control our lives in ways big and small, and in ways that range from subtle to a punch in the face.

In Canada, the federal government’s environmental policies are the most obvious example of this interference. The Liberals have banned plastic straws and plastic bags; even compostable bags are banned in grocery stores because they resemble plastic. Such bans are pointless irritants that make shopping more expensive, and life slightly less enjoyable as paper straws dissolve in one’s drink. People might dismiss these concerns as simply minor inconveniences, but this is how most people experience government policy, by being forced to replace their bag of plastic bags that they were already reusing, with more expensive, less useful options.

Next up, the Liberals are exploring options to bring in environmental regulations for clothing. The cost of clothes has actually gone down in recent years, so leave it to Ottawa to look for ways to bring the cost back up and to limit options.

There is also the plan to essentially force Canadians to purchase electric vehicles, that nobody would otherwise want, through government mandates to phase out the sale of gas-powered cars and trucks.

On a larger scale, the government is attempting to restrict the kind of work people do, specifically work in the oil and gas industry, through steep emissions targets, which will close off lucrative job opportunities in western oilfields. It will also limit the kinds of fuels people will be able to use to heat their homes.

There are also policies that the Canadian government hasn’t implemented, but which green activists have endorsed, such as the banning of gas stoves and the ludicrous suggestion from some academics that “climate lockdowns” be implemented to help cut emissions.

It is possible to be supportive of all these policies, despite their paternalistic and job-killing nature, but pretending that no one is trying to, or that no one wants to, interfere with our liberty is not a credible position to take.

August 19, 2024

If you’ve never worked in the private sector, you have no idea how regulations impact businesses

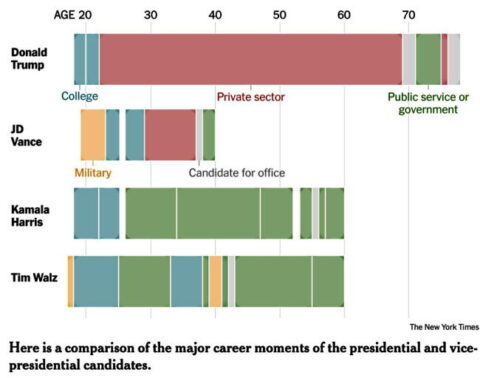

In the National Post, J.D. Tuccille explain why Democratic candidates like Kamala Harris and Tim Walz who have spent little or no time in the non-government world have such rosy views of the benefits of government control with no concept of the costs such control imposes:

The respective public versus private sector experiences of the 2024 Presidential/Vice Presidential candidates.

New York Times

In broad terms, Democrats have faith in government while the GOP is skeptical — though a lot of Republicans are willing to suspend disbelief when their party controls the executive branch.

The contrast between the two parties can be seen in stark terms in the resumes of the two presidential and vice-presidential tickets. The New York Times made it easier to compare them earlier this month when it ran charts of the career timelines of Trump, J.D. Vance, Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. Their roles at any given age were colour-coded for college, military, private sector, public service or politics, federal government and candidate for federal office.

Peach is the colour used by the Times to indicate employment in the private sector, which produces the opportunities and wealth that are mugged away (taxation is theft by another name, after all) to fund all other sectors. It appears under the headings of “businessman” and “television personality” for Trump and as “lawyer and venture capitalist” for Vance. But private-sector peach appears nowhere in the timelines for Harris and Walz. Besides, perhaps, some odd jobs when they were young, neither of the Democrats has worked in the private sector.

Now, not all private-sector jobs are created equal. Some of the Republican presidential candidate’s ventures, like Trump University, have been highly sketchy, as are some of his practices — he’s openly boasted about donating to politicians to gain favours (though try to do business in New York without greasing palms). I’m not sure I’d want The Apprentice on my resume. But there must be some value to working on the receiving end of the various regulations and taxes government officials foist on society rather than spending one’s career brainstorming more rules without ever suffering the consequences.

In 1992, former U.S. senator and 1972 Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern penned a column for the Wall Street Journal about the challenges he encountered investing in a hotel after many years in government.

“In retrospect, I … wish that during the years I was in public office, I had had this firsthand experience about the difficulties business people face every day,” he wrote. He bemoaned “federal, state and local rules” passed with seemingly good intentions but little thought to the burdens and costs they imposed.

The lack of private sector stints in the career timelines of Harris and Walz means that, like pre-hotel McGovern, they’ve never had to worry about what it’s like to suffer the policies of a large and intrusive government.

That said, it’s possible to overstate the lessons learned by Republicans and Democrats from their different experiences. Vance, despite having worked to fund and launch businesses, has, since being elected to the U.S. Senate, advocated capturing the regulatory state and repurposing it for political uses, including punishing enemies.

Not only does power corrupt, but it does so quickly.