I always laugh when I hear the phrase, “Dance like nobody’s watching.” It’s 2015. Everybody’s watching.

Jim Treacher, “Mac & Cheese Dude Is Sorry For Being An [Incredibly Unpleasant Person]”, The Daily Caller, 2015-10-13.

December 4, 2015

QotD: “Dance like nobody’s watching”

November 23, 2015

Do you have a smartphone? Do you watch TV? You might want to reconsider that combination

At The Register, Iain Thomson explains a new sneaky way for unscrupulous companies to snag your personal data without your knowledge or consent:

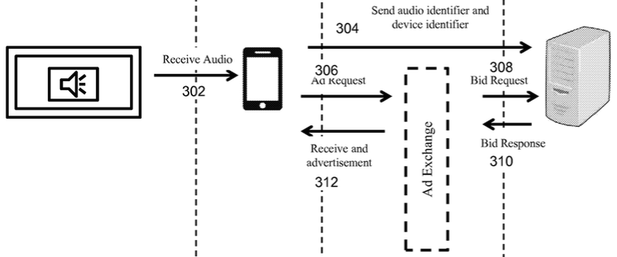

Earlier this week the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) warned that an Indian firm called SilverPush has technology that allows adverts to ping inaudible commands to smartphones and tablets.

Now someone has reverse-engineered the code and published it for everyone to check.

SilverPush’s software kit can be baked into apps, and is designed to pick up near-ultrasonic sounds embedded in, say, a TV, radio or web browser advert. These signals, in the range of 18kHz to 19.95kHz, are too high pitched for most humans to hear, but can be decoded by software.

An application that uses SilverPush’s code can pick up these messages from the phone or tablet’s builtin microphone, and be directed to send information such as the handheld’s IMEI number, location, operating system version, and potentially the identity of the owner, to the application’s backend servers.

Imagine sitting in front of the telly with your smartphone nearby. An advert comes on during the show you’re watching, and it has a SilverPush ultrasonic message embedded in it. This is picked up by an app on your mobile, which pings a media network with information about you, and could even display followup ads and links on your handheld.

“This kind of technology is fundamentally surreptitious in that it doesn’t require consent; if it did require it then the number of users would drop,” Joe Hall, chief technologist at CDT told The Register on Thursday. “It lacks the ability to have consumers say that they don’t want this and not be associated by the software.”

Hall pointed out that very few of the applications that include the SilverPush SDK tell users about it, so there was no informed consent. This makes such software technically illegal in Europe and possibly in the US.

October 17, 2015

Ken White of Popehat.com Talks Blogging, Anonymous Speech

Published on 13 Oct 2015

Ken White, founder of the influential group blog Popehat, tells FIRE how he got interested in the First Amendment and discusses anonymous speech on the Internet.

White, who writes for Popehat on a variety of issues, including the First Amendment, criminal justice, and the legal system, said a college project at Stanford University “during … one of the upsurges of controversy on campus about speech codes and speech issues,” opened his eyes to the nuances of the First Amendment.

“I wound up doing my senior honors thesis in college with a law school professor on the subject of legal restrictions on hate speech,” White said. “I thought it was very much emblematic of a very American problem, and that is: How do we express our disapproval — our moral disapproval — for bad things like bigotry, while not restricting liberties?”

Popehat seems to be a space created to do exactly that. The forum has evolved into a blog the contributors describe as a “group complaint” about “whatever its authors want.”

That freedom hasn’t always come so easily for White, who blogged anonymously for more than five years due to concerns his honest blogging might harm his career. He still thinks anonymous speech provides both benefits and drawbacks.

“I think the right to anonymous speech is very central in the First Amendment and in American life,” said White. “Throughout American history, people have said unpopular things, incendiary things, politically dangerous things behind the shield of anonymity. A lot of bad things come with that. There’s some really terrible, immoral, anonymous behavior on the Internet.”

White said there’s also a risk to writing anonymously, and that even while he benefitted from posting behind the security of an online persona, he supports the rights of others to try and discover his true identity. Eventually, White said he gave up the pretext and started blogging under his own name.

For more from White, including why free speech “catchphrases” harm First Amendment discourse, watch the above video.

September 30, 2015

Russia’s “bounty” on TOR

Strategy Page on the less-than-perfect result of Russia’s attempt to get hackers to crack The Onion Router for a medium-sized monetary prize:

Back in mid-2014 Russia offered a prize of $111,000 for whoever could deliver, by August 20th 2014, software that would allow Russian security services to identify people on the Internet using Tor (The Onion Router), a system that enables users to access the Internet anonymously. On August 22nd Russia announced that an unnamed Russian contractor, with a top security clearance, had received the $111,000 prize. No other details were provided at the time. A year later is was revealed that the winner of the Tor prize is now spending even more on lawyers to try and get out of the contract to crack Tor’s security. It seems the winners found that their theoretical solution was too difficult to implement effectively. In part this was because the worldwide community of programmers and software engineers that developed Tor is constantly upgrading it. Cracking Tor security is firing at a moving target and one that constantly changes shape and is quite resistant to damage. Tor is not perfect but it has proved very resistant to attack. A lot of people are trying to crack Tor, which is also used by criminals and Islamic terrorists was well as people trying to avoid government surveillance. This is a matter of life and death in many countries, including Russia.

Similar to anonymizer software, Tor was even more untraceable. Unlike anonymizer software, Tor relies on thousands of people running the Tor software, and acting as nodes for email (and attachments) to be sent through so many Tor nodes that it was believed virtually impossible to track down the identity of the sender. Tor was developed as part of an American government program to create software that people living in dictatorships could use to avoid arrest for saying things on the Internet that their government did not like. Tor also enabled Internet users in dictatorships to communicate safely with the outside world. Tor first appeared in 2002 and has since then defied most attempts to defeat it. The Tor developers were also quick to modify their software when a vulnerability was detected.

But by 2014 it was believed that NSA had cracked TOR and others may have done so as well but were keeping quiet about it so that the Tor support community did not fix whatever aspect of the software that made it vulnerable. At the same time there were alternatives to Tor, as well as supplemental software that were apparently uncracked by anyone.

September 10, 2015

Making it easy for governments to monitor texts, emails, and other messages

Megan McArdle explains that while it’s quite understandable why governments want to maintain their technological ability to read private, personal communications … but that’s not sufficient justification to just give in and allow them the full access they claim that they “need”:

Imagine, if you will, a law that said all doors had to be left unlocked so that the police could get in whenever they needed to. Or at the very least, a law mandating that the government have a master key.

That’s essentially what some in the government want for your technology. As companies like Apple and Google have embraced stronger encryption, they’re making it harder for the government to do the kind of easy instant collection that companies were forced into as the government chased terrorists after 9/11.

And how could you oppose that government access? After all, the government keeps us safe from criminals. Do you really want to make it easier for criminals to evade the law?

The analogy with your home doors suggests the flaw in this thinking: The U.S. government is not the only entity capable of using a master key. Criminals can use them too. If you create an easy way to bypass security, criminals — or other governments — are going to start looking for ways to reproduce the keys.

[…]

Law enforcement is going to pursue strategies that maximize the ability to catch criminals or terrorists. These are noble goals. But we have to take care that in the pursuit of these goals, the population they’re trying to protect is not forgotten. Every time we open more doors for our own government, we’re inviting other unwelcome guests to join them inside.

I don’t really blame law enforcement for pushing as hard as possible; rare is the organization in history that has said, “You know, the world would be a better place if I had less power to do my job.” But that makes it more imperative that the rest of us keep an eye on what they’re doing, and force the law to account for tradeoffs, rather than the single-minded pursuit of one goal.

August 28, 2015

Google and the (bullshit) European “right to be forgotten”

Techdirt‘s Mike Masnick points and laughs at a self-described consumerist organization’s attempt to force Google to apply EU law to the rest of the world, by way of an FTC complaint:

If you want an understanding of my general philosophy on business and economics, it’s that companies should focus on serving their customers better. That’s it. It’s a very customer-centric view of capitalism. I think companies that screw over their customers and users will have it come back to bite them, and thus it’s a better strategy for everyone if companies focus on providing good products and services to consumers, without screwing them over. And, I’m super supportive of organizations that focus on holding companies’ feet to the fire when they fail to live up to that promise. Consumerist (owned by Consumer Reports) is really fantastic at this kind of thing, for example. Consumer Watchdog, on the other hand, despite its name, appears to have very little to do with actually protecting consumers’ interests. Instead, it seems like some crazy people who absolutely hate Google, and pretend that they’re “protecting” consumers from Google by attacking the company at every opportunity. If Consumer Watchdog actually had relevant points, that might be useful, but nearly every attack on Google is so ridiculous that all it does is make Consumer Watchdog look like a complete joke and undermine whatever credibility the organization might have.

In the past, we’ve covered an anti-Google video that company put out that contained so many factual errors that it was a complete joke (and was later revealed as nothing more than a stunt to sell some books). Then there was the attempt to argue that Gmail was an illegal wiretap. It’s hard to take the organization seriously when it does that kind of thing.

Its latest, however, takes the crazy to new levels. John Simpson, Consumer Watchdog’s resident “old man yells at cloud” impersonator, recently filed a complaint with the FTC against Google. In it, he not only argues that Google should offer the “Right to be Forgotten” in the US, but says that the failure to do that is an “unfair and deceptive practice.” Really.

As you know by now, since an EU court ruling last year, Google has been forced to enable a right to be forgotten in the EU, in which it will “delink” certain results from the searches on certain names, if the people argue that the links are no longer “relevant.” Some in the EU have been pressing Google to make that “right to be forgotten” global — which Google refuses to do, noting that it would violate the First Amendment in the US and would allow the most restrictive, anti-free speech regime in the world to censor the global internet.

But, apparently John Simpson likes censorship and supporting free speech-destroying regimes. Because he argues Google must allow such censorship in the US. How could Google’s refusal to implement “right to be forgotten” possibly be “deceptive”? Well, in Simpson’s world, it’s because Google presents itself as “being deeply committed to privacy” but then doesn’t abide by a global right to be forgotten. Really.

August 2, 2015

Thinking about realistic security in the “internet of things”

The Economist looks at the apparently unstoppable rush to internet-connect everything and why we should worry about security now:

Unfortunately, computer security is about to get trickier. Computers have already spread from people’s desktops into their pockets. Now they are embedding themselves in all sorts of gadgets, from cars and televisions to children’s toys, refrigerators and industrial kit. Cisco, a maker of networking equipment, reckons that there are 15 billion connected devices out there today. By 2020, it thinks, that number could climb to 50 billion. Boosters promise that a world of networked computers and sensors will be a place of unparalleled convenience and efficiency. They call it the “internet of things”.

Computer-security people call it a disaster in the making. They worry that, in their rush to bring cyber-widgets to market, the companies that produce them have not learned the lessons of the early years of the internet. The big computing firms of the 1980s and 1990s treated security as an afterthought. Only once the threats—in the forms of viruses, hacking attacks and so on—became apparent, did Microsoft, Apple and the rest start trying to fix things. But bolting on security after the fact is much harder than building it in from the start.

Of course, governments are desperate to prevent us from hiding our activities from them by way of cryptography or even moderately secure connections, so there’s the risk that any pre-rolled security option offered by a major corporation has already been riddled with convenient holes for government spooks … which makes it even more likely that others can also find and exploit those security holes.

… companies in all industries must heed the lessons that computing firms learned long ago. Writing completely secure code is almost impossible. As a consequence, a culture of openness is the best defence, because it helps spread fixes. When academic researchers contacted a chipmaker working for Volkswagen to tell it that they had found a vulnerability in a remote-car-key system, Volkswagen’s response included a court injunction. Shooting the messenger does not work. Indeed, firms such as Google now offer monetary rewards, or “bug bounties”, to hackers who contact them with details of flaws they have unearthed.

Thirty years ago, computer-makers that failed to take security seriously could claim ignorance as a defence. No longer. The internet of things will bring many benefits. The time to plan for its inevitable flaws is now.

August 1, 2015

The Streisand Effect – Trying to Hide Things On The Internet I INTO CONTEXT

Published on 6 Jan 2015

One of the biggest news stories this Christmas was the (un-)cancelled release of Sony Pictures’ movie The Interview. In the movie, Seth Rogan and James Franco try to assassinate North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un. After terror threats against movie theatres showing the film, Sony cancelled the release of the movie. This ultimately increased the movies attention and made the later online release the most successful one this year. Actually, there is a name for this kind of phenomenon: the Streisand Effect. In this episode of INTO CONTEXT, Indy explains why it’s not always smart to try to hide things on the internet.

July 17, 2015

The case for encryption – “Encryption should be enabled for everything by default”

Bruce Schneier explains why you should care (a lot) about having your data encrypted:

Encryption protects our data. It protects our data when it’s sitting on our computers and in data centers, and it protects it when it’s being transmitted around the Internet. It protects our conversations, whether video, voice, or text. It protects our privacy. It protects our anonymity. And sometimes, it protects our lives.

This protection is important for everyone. It’s easy to see how encryption protects journalists, human rights defenders, and political activists in authoritarian countries. But encryption protects the rest of us as well. It protects our data from criminals. It protects it from competitors, neighbors, and family members. It protects it from malicious attackers, and it protects it from accidents.

Encryption works best if it’s ubiquitous and automatic. The two forms of encryption you use most often — https URLs on your browser, and the handset-to-tower link for your cell phone calls — work so well because you don’t even know they’re there.

Encryption should be enabled for everything by default, not a feature you turn on only if you’re doing something you consider worth protecting.

This is important. If we only use encryption when we’re working with important data, then encryption signals that data’s importance. If only dissidents use encryption in a country, that country’s authorities have an easy way of identifying them. But if everyone uses it all of the time, encryption ceases to be a signal. No one can distinguish simple chatting from deeply private conversation. The government can’t tell the dissidents from the rest of the population. Every time you use encryption, you’re protecting someone who needs to use it to stay alive.

July 16, 2015

QotD: The proper role of government

Good government is a constable — it keeps the peace and protects property. Parasitic government — which is, sad to say, practically the only form known in the modern world — is at its best a middleman that takes a cut of every transaction by positioning itself as a nuisance separating you from your goals. At its worst, it is functionally identical to a goon running a protection racket.

[…]

The desire to be left alone is a powerful one, and an American one. It is not, contrary to the rhetoric proffered by the off-brand Cherokee princess currently representing the masochistic masses of Massachusetts in the Senate, an anti-social sentiment. It is not that we necessarily desire to be left alone full stop — it is that we desire to be left alone by people who intend to forcibly seize our assets for their own use. You need not be a radical to desire to live in your own home, to drive your own car, and to perform your own work without having to beg the permission of a politician — and pay them 40 percent for the privilege.

Principles are dangerous things — whiskey is for drinking, water and principles are for fighting over. The anti-ideological current in conservative thinking appreciates this: If we all seek complete and comprehensive satisfaction of our principles, then there will never be peace. This is why scale matters and why priorities matter. In a world in which the public sector consumes 5 percent of my income and uses it for such legitimate public goods as law enforcement and border security, I do not much care whether the tax system is fair or just on a theoretical level; and while I may resent it as a matter of principle, the cost of my consent is relatively low, and I have other things to think about. But in a world in which the parasites take half, and use it mainly to buy political support from an increasingly ovine and dependent electorate, then I care intensely.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Property and Peace”, National Review, 2014-07-20.

July 13, 2015

Do photographers have any rights left?

I no longer do much in the way of “serious” photography (my digital SLR has been out of service for a couple of years now), but I still occasionally do a bit of cellphone photography when the occasion arises. On the byThom blog, Thom Hogan provides a long (yet not exhaustive) list of things, places, and people who are legally protected from being photographed in various jurisdictions … and it gets worse:

Funny thing is, smartphones are so ubiquitous and so small, many of those bans just aren’t enforceable against them in their natural state (e.g., without selfie stick), especially if they’re used discriminatingly.

I’m all for privacy, but privacy doesn’t exist in public spaces as far as I’m concerned. Indeed, I’d argue that even in private spaces (malls, for example), that if you’re open for and soliciting business to the public, you’re a public space. As for Copyright, placing artwork in open public spaces (e.g. Architecture) probably ought to convey some sort of Fair Use right to the public, though in Europe we’re seeing just the opposite start to happen. FWIW, I no longer visit and thus don’t photograph in two countries because of national laws regarding photography. Be careful what you wish for, Mr. Bureaucracy; laws often have unintended consequences. As in reducing my interest in visiting your country.

About half of this site’s readers actively practice some form of travel photography, either during vacations or while traveling for business. Note how many of the restrictions on photography start to apply against those that are traveling (locally or farther afield). It’s always easy to impose laws on people who don’t vote for you. it’s why rental car and hotel room taxes are so high, after all.

What prompted this article, though, wasn’t any of the latest photography ban talk, though. Here in Pennsylvania we have fairly restrictive regulations on “recording” another person (e.g. conversations, phone calls, meetings, etc.). In some states, it only takes one party to consent for a recording to be legal. Here in Pennsylvania it takes all parties to consent to being recorded.

H/T to Clive for the link.

June 29, 2015

Europe institutionalizes the “memory hole”

Brendan O’Neill on the European “right to be forgotten”:

“He stepped across the room. There was a memory hole in the opposite wall. O’Brien lifted the grating. Unseen, the frail slip of paper was whirling away on the current of warm air; it was vanishing in a flash of flame. O’Brien turned away from the wall. ‘Ashes,’ he said. ‘Not even identifiable ashes. Dust. It does not exist. It never existed.'”

This is the moment in Nineteen Eighty-Four when O’Brien, an agent of the Thought Police who tortures Winston Smith in Room 101, dumps into a memory hole an inconvenient news story. It’s an 11-year-old newspaper cutting which confirms that three Party members who were executed for treason could not have been guilty. “It does exist!” wails Winston. “It exists in memory. I remember it. You remember it.” O’Brien, mere seconds after plunging the item into the memory hole, replies: “I do not remember it.”

Of all the horrible things in Nineteen Eighty-Four that have come true in recent years — from rampant thought-policing to the spread of CCTV cameras — surely the memory hole, the institutionalisation of forgetting, will never make an appearance in our supposedly open, transparent young century? After all, ours is a “knowledge society,” where info is power and Googling is on pretty much every human’s list of favourite pastimes.

Think again. The memory hole is already here. In Europe, anyway. We might not have actual holes into which pesky facts are dropped so that they can be burnt in “enormous furnaces.” But the EU-enforced “right to be forgotten” does empower individual citizens in Europe, with the connivance of Google, to behave like little O’Briens, wiping from internet search engines any fact they would rather no longer existed.

June 23, 2015

June 19, 2015

The EFF’s Privacy Badger

Earlier this month, Noah Swartz exhorted the Mozilla folks to put some energy and effort behind the Firefox Tracking Protection technology. While we wait for that to come to fruition, he also recommends the Electronic Frontiers Foundation’s Privacy Badger for Firefox users:

In her blog post, [Monica] Chew flags the need for Mozilla’s management to ensure that this essential protection reaches users, and to recognize that “current advertising practices that enable ‘free’ content are in direct conflict with security, privacy, stability, and performance concerns.” Since advertising industry groups flatly refused to respect the Do Not Track header as a privacy opt-out from data collection, the only line of defense we have against non-consensual online tracking is our browsers.

Safari and Internet Explorer have taken important steps to protect their users against web tracking: Safari blocks third party cookies out of the box, and IE offers a prominent tracker-blocking option. But mainstream users of open source browsers are out of luck. Until that changes, our Privacy Badger add-on for Firefox and Chrome remains perhaps the only one-click solution for users who want to protect their privacy as they browse the web. Since Privacy Badger requires no configuration, we encourage any user who is concerned about online tracking to add it to their browser.

June 14, 2015

More on that Reason grand jury subpoena

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Ryan Radia discusses the free-speech-quashing subpoena issued by a federal prosecutor in New York state:

In late May, Judge Katherine Forrest, who sits on the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, sentenced Ulbricht to life in prison. This sentence was met with mixed reactions, with many commentators criticizing Judge Forrest for handing down what they perceived as an exceedingly harsh sentence.

A few Reason users, some of whom may have followed Reason’s extensive coverage of the fascinating trial, apparently found Ulbricht’s sentence especially infuriating.

One commenter argued that “judges like these … should be taken out back and shot.” Another user, purporting to correct the preceding comment, wrote that “it’s judges like these that will be taken out back and shot.” A follow-up comment suggested the use of a “wood chipper,” so as not to “waste ammunition.” And a user expressed hope that “there is a special place in hell reserved for that horrible woman.”

Within hours, the office of Preet Bharara, the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, sent Reason a subpoena for these commenters’ identifying information “in connection with an official criminal investigation of a suspected felony being conducted by a federal grand jury.”

This doesn’t mean a grand jury actually asked about the commenters; instead, in federal criminal investigations, it’s typically up to the US Attorney to decide when to issue a subpoena “on behalf” of a grand jury.

[…]

Even if this subpoena is valid under current law — more on that angle in a bit — the government made a serious mistake in seeking to force Reason to hand over information that could uncover the six commenters’ identities.

Unless the Department of Justice is investigating a credible threat to Judge Forrest with some plausible connection to the Reason comments at issue, this subpoena will serve only to chill hyperbolic — but nonetheless protected — political speech by anonymous Internet commenters.