Published on 11 May 2015

The American ideal of limited government on life support. Is it time for civil disobedience? Charles Murray says yes. Murray has been writing on government overreach for more than 30 years. His new book, By The People, is a blueprint for taking back American liberty. Jonah Goldberg sits down with Murray to discuss civil unrest in Baltimore, the scope of the government, and why bureaucrats should wear body cameras.

According to AEI scholar, acclaimed social scientist, and bestselling author Charles Murray, American liberty is under assault. The federal government has unilaterally decided that it can and should tell us how to live our lives. If we object, it threatens, “Fight this, and we’ll ruin you.” How can we overcome regulatory tyranny and live free once again? In his new book, By the People: Rebuilding Liberty Without Permission (Crown Forum, May 2015), Murray offers provocative solutions.

May 16, 2015

Charles Murray and Jonah Goldberg on civil disobedience in America

May 11, 2015

Nepal’s tragic unpreparedness for disaster

In The Walrus, Manjushree Thapa explains why Nepal was so badly prepared for the earthquake:

Following the April 25 earthquake, Nepalis have had to learn the value of preparedness in the most painful way possible. In the aftermath, Pushpa Acharya, a Nepali friend at the University of Toronto, observed, “Knowledge was not our problem.” Indeed. We all knew that our country sits on an active fault line, where the subcontinent collided with the Eurasian plate with such force it created the Himalayas. The last big quake took place in 1934. Others have since struck, but none with the force of 1934’s 8.0 or April 25’s 7.9. We knew that a big earthquake was due.

It was our duty to prepare, and though some of us did so individually, as a society we ignored the warnings. In the past ten days, during search and rescue, and then the beginnings of relief, we’ve had to do some hard thinking about how our country could become more responsible going forward. The root problem may seem obvious: Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. Its poverty is, however, a symptom of our history of ill governance, and the reason for our national failure to prepare, which has kept us from becoming a functioning democracy.

When the earthquake struck, the country was in a deep and deeply depressing stupor. The governing parties — a coalition of the Nepali Congress Party and the Unified Marxist Leninists — had reached an impasse with Nepal’s thirty-three opposition parties about what kind of constitution to draft. There was no plan for the country as a whole, let alone in the case of an emergency. The drafting of a constitution has preoccupied, confounded, and eluded Nepal’s polity since 2006, when the Maoists ended a ten-year insurgency to join forces with other parties to remove Gyanendra Bir Bikram Shah. Nepal’s king had used the war as an excuse to end a fragile fifteen-year spell of democracy and install his own military-backed rule. A mass movement restored democracy, and the subsequent peace process promised to restructure the country along just and equitable lines through the drafting of a new constitution

April 24, 2015

Relative and absolute poverty

We in the west are so rich, in historical terms, that we are losing our grasp on what poverty really has been for the majority of humankind for the majority of our recorded history:

People generally just don’t get what poverty actually means. This is a charge often enough aimed at me and people like me, well off white guys who pontificate upon economics. But those making that charge often enough don’t actually understand what real poverty means. So, here’s a nice example of it. There’s a campaign in New York to insist that SNAP (ie, food stamps) should not be cut. Views on that can vary either way: I’m generally in favour of a larger welfare state than the one the US has at present so I’m probably against such a cut. But that’s a political point and not the one I’m interested in here. Rather, I want to point out just quite how rich someone getting food stamps is on any global or historical basis.

Yes, you did read that right: how rich someone getting food stamps is. As one example, the food stamp allocation in New York State appears to be $29 per person per week in a family receiving the full possible allocation. That, on its own, is a yearly income of $1,508 and that’s an amount that puts you, on its own, in the top 50% of all income recipients in the world. No, really, you can look that up with this little calculator. More than half of humanity is poorer than someone who only gets the New York food stamp allocation.

All of which gives us an interesting little look into the difference between absolute poverty and relative poverty. For, obviously, the people who are receiving food stamps in New York are those we consider to be poor in our own society. And in our own society, they are indeed poor, as Adam Smith pointed out with his linen shirt example. It’s not necessary for a working man to have a linen shirt, he’s not poor because he cannot afford one. But if you live in a society where you are considered to be poor if you cannot afford a linen shirt, and you cannot afford one, then in that society you are of course poor. This is relative poverty, more usefully known not as a measure of poverty but of inequality.

April 22, 2015

“Victorian style poverty” in the UK

In a recent Forbes column, Tim Worstall pours scorn on the recent claim that some British children are living in “Victorian conditions”:

There’s a very large difference between arguing that we have Victorian style (for those unacquainted with British practise, this means late 19th century style) poverty in the UK and that we have Victorian style inequality in the UK. That second is at least arguably possible, although untrue, while the first is simply a flat out untruth. There is nothing even remotely akin to 19th century poverty in the UK today. Nor is there, of course, in any of the industrialised nations. The problem stems from people simply not understanding how poor the past was.

The claim is made this morning in The Guardian:

Many children are living in Victorian conditions – it’s an inequality timebomb

That second assertion could be true but is a matter for another day. That first is just wrong.

I was reminded of this by the teaching union NASUWT’s warning this week that there are children in this country living in “Victorian conditions”, turning to charity for regular meals and going without a winter coat.

“Going without a winter coat” might be something we’d like to remedy (and yes, I think we would like to do so) but it’s not a reminder of Victorian levels of poverty, it’s nothing like it at all. It’s necessary to actually understand what Victorian poverty was. Late 19th century Britain had some 25% of the population living at or below the subsistence level. This subsistence level is not a measure of inequality, nor of the lack of winter clothes. It is a measure of gaining enough calories each day in order to prolong life. This is the sort of subsistence level that Malthus and Ricardo were talking about. The sort of level of poverty that the World Bank currently uses as a measure of “absolute poverty”.

This absolute poverty is set at $1.25 per person per day. No, this is not the number that can be spent upon food per person per day. This is the amount that can be spent upon everything per person per day. This covers shelter, clothing, heating, cooking, food, education, pensions, health care, absolutely everything. This number is also inflation adjusted, so we are not talking about $1.25 a day when bread was one cent a gallon loaf. This number is also Purchasing Power Parity adjusted: so we are not talking about lentils costing two cents a tonne in India and £3 a kg in Tesco. We are adjusting for those price differences across geography and time.

Just to note, by these PPP and inflation adjusted numbers, being on the minimum wage in the UK puts you in the top 10% of all income earners in the current world. Being on nothing at all but benefits would put you into the top 20%.

Up to 25% of the population of Britain were that badly off in the late Victorian era: “Actual real starvation to death as a result of poverty was not unknown, even that late, as late as 1890.”

April 21, 2015

Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore’s amazing economic success

Earlier this month, Alvaro Vargas Llosa examined the economic success of Singapore under the authoritarian rule of Lee Kuan Yew:

Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s legendary statesman, who died last month at the age of 91, posed a challenge to those of us who believe in political and economic freedom (and all other freedoms). His combination of authoritarianism and economic freedom, of social engineering and self-reliance, worked. The result was a society that is more prosperous than most others, but free only in some respects.

For years, the best examples one could come up with to show that the marriage of economic and political liberty could work were the liberal democracies of the developed world, whose achievements originated in centuries past and different circumstances.

Lee Kuan Yew’s credentials became strong as many countries that also gained independence in the 1950s or 1960s opted for a mix of nativism and collectivism that kept them poor while tiny Singapore, with no natural resources, emerged as an economic powerhouse. While Mao, Ho Chi Minh, and Castro — not to cite Mobutu, Idi Amin Dada, and others — destroyed the chances of a decent life for many generations, Lee Kuan Yew created the conditions for a 124-fold increase in Singapore’s per capita income in half a century.

[…]

Singapore’s case is exceptional, which makes it a tough challenge for those of us who think freedom is best served by not carving it up. My belief is that Singapore has been able to preserve its curious mix because of the absence of prosperous liberal democracies around it. But its model is based on globalization, and it’s therefore porous to good ideas.

In a world in which more countries, including Asian ones, end up successfully embracing democracy under the rule of law as well as free trade, it will be impossible for the city-state to avoid the comparison and the contagion. It is one thing to preserve an authoritarian model because your neighbors espouse a less successful one, and quite another to perpetuate it in the face of equally or even more successful societies that espouse a freer model.

April 10, 2015

QotD: Zoning hurts the poor

One kind of regulation that was actually intended to harm the poor, and especially poor minorities, was zoning. The ostensible reason for zoning was to address unhealthy conditions in cities by functionally separating land uses, which is called “exclusionary zoning.” But prior to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, some municipalities had race-based exclusionary land-use regulations. Early in the 20th century, several California cities masked their racist intent by specifically excluding laundry businesses, predominantly Chinese owned, from certain areas of the cities.

Today, of course, explicitly race-based, exclusionary zoning policies are illegal. But some zoning regulations nevertheless price certain demographics out of particular neighborhoods by forbidding multifamily dwellings, which are more affordable to low- or middle-income individuals. When the government artificially separates land uses and forbids building certain kinds of residences in entire districts, it restricts the supply of housing and increases the cost of the land, and the price of housing reflects those restrictions.

Moreover, when cities implement zoning rules that make it difficult to secure permits to build new housing, land that is already developed becomes more valuable because you no longer need a permit. The demand for such developed land is therefore artificially higher, and that again raises its price.

Sandy Ikeda, “Shut Out: How Land-Use Regulations Hurt the Poor”, The Freeman, 2015-02-05.

April 8, 2015

April 5, 2015

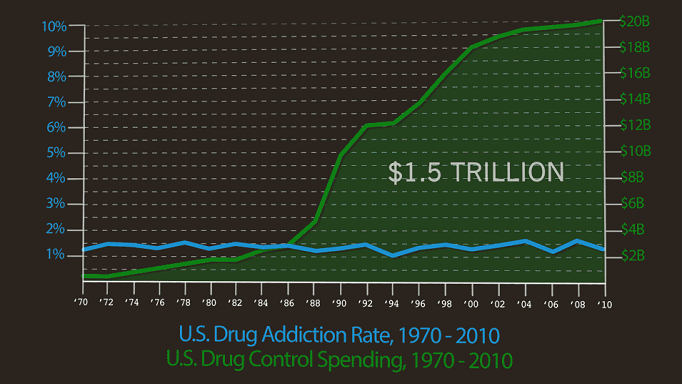

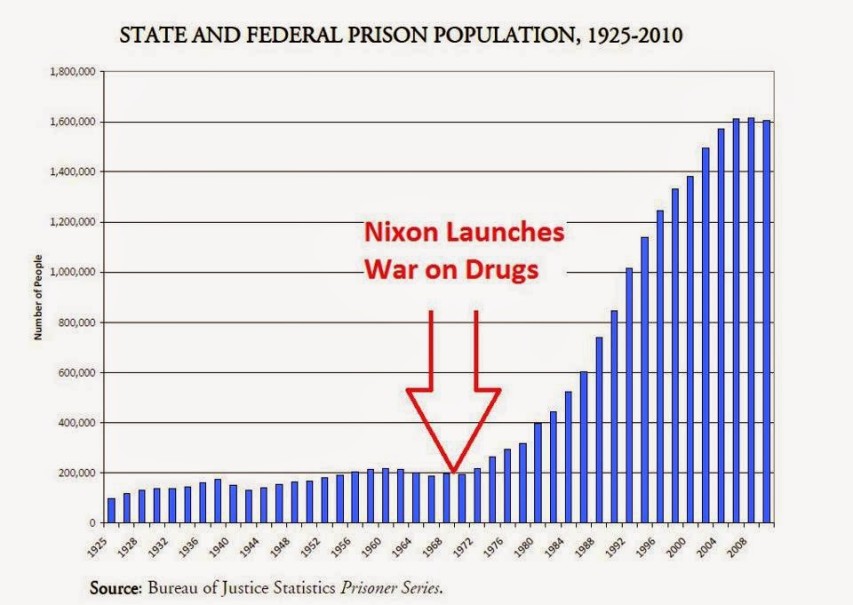

The war on drugs in two charts

I saw this on Google+ and thought the two graphics included in the post were interesting enough to present on their own — because they pretty much tell the whole story in a glance:

In 1969, the prison population was 200,000 and the overall population was about 200 million people. This means that approximately 0.1% of all Americans were in prison in 1969. As of 2010, the prison population had expanded to 1.6 million while the overall population was 309 million. Therefore, the current prison population is 0.5%. The prison population has expanded 5 times when adjusted for population size while the rate of drug addiction has remained largely constant. I do not believe that any reasonable person can look at the statistics on incarceration versus drug usage and come to any conclusion other than that the Drug War has been an immense cataclysm for the American people and that this cataclysm has fallen horrifically and disproportionately upon the poor. From a drug usage standpoint the inner cities have not improved in the slightest when it comes to overdoses and other tertiary consequences of drug use and we have simultaneously turned our inner cities into armed police states where the inhabitants are frequently terrified of the police, where the police engage in the worst sorts of paramilitary tactics, and where a large portion of young men are hurled into prison cells and ruined in the prime of their lives.

But none of these bourgeoisie facts and evidence shall deter Mr. Walters from his noble, righteous quest! No, he knows the evils of marijuana which shall be visited disproportionately upon the poor, and he will not rest until such toxins are driven entirely from the field:

The focus on marijuana legalization trades on the public perception that the drug does little damage, and hence, that any criminal justice penalty for its use is an unnecessary affront. In fact, marijuana use does serious harm, and its legalization promises more use by the most vulnerable in communities like Angela Dawson’s Oliver neighborhood.

Personally, and I do realize this would shock Mr. Walters, I actually don’t care how damaging marijuana is to its users. Provided its users are of legal age and therefore are capable of consenting to its use, whether or not it is ‘damaging’ is of no relevance to me — consuming massive quantities of sugar is damaging, large amounts of fat is damaging, failure to exercise is damaging, drinking to excess is damaging — yet none of these are, or should be, illegal. Even if you prove the negative consequences of weed, it doesn’t matter — it is not the responsibility of the state to treat its citizens like children in need of mollycoddling and governmentally sponsored salvation and it certainly is neither the duty nor the purpose of the state to save us from the consequences of our own decisions.

March 30, 2015

The built-in advantages of the traditional family structure

Megan McArdle on the reactions to a recent book dealing with traditional and non-traditional families:

Robert Putnam’s Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis has touched off a wave of print and digital commentary. The book chronicles a growing divide between the way affluent kids are raised, in two-parent homes whose parents invest heavily in educating their kids, and the very different, very unstable homes in which poorer kids generally grow up.

Naturally, social conservatives are delighted with this lengthy examination of the problems created by unstable families, even if they are not equally delighted with Putnam’s recommendations (more government programs). Equally naturally, there is pushback from those who see the problem as primarily one of economics and insufficient government spending, as well as from those who argue that there are lots of good ways to raise kids outside the straitjacket of mid-century, middle-class mores.

I have been trying to find a more delicate way to phrase this, but I can’t: This is nonsense. The advantages that two people raising their own biological or jointly adopted children have over “nontraditional” family arrangements are too obvious to need enumeration, but apparently mere obviousness is not enough to forestall contrary arguments, so let me enumerate them anyway.

Raising children the way an increasing percentages of Americans are — in loosely attached cohabitation arrangements that break up all too frequently, followed by the formation of new households with new children by different parents — is an enormous financial and emotional drain. Supporting two households rather than one is expensive, and it diverts money that could otherwise be invested in the kids. The parent in the home has no one to help shoulder the load of caring for kids, meaning less investment of time and more emotional strain on the custodial parent. Children will spend less time with their noncustodial parent, especially if that parent has other offspring. Add in conflict between the parents over money and time, and it can infect relationships with the children. As one researcher told me when I wrote an article on the state of modern marriage, you frequently see fathers investing time and money with the kids whose mother they get along with the best, while the other children struggle along on crumbs.

People often argue that extended families can substitute, but of course, two-parent families also have extended families — two of them — so single-parent families remain at a disadvantage, especially because other members of the extended family are often themselves struggling with the challenges of single parenthood. Extended families just can’t substitute for the benefits of a two-parent family. Government can’t, either; universal preschool is not going to make up for an uninvolved parent, or one stretched too thin to give their kids enough time. Government can sand the rough edges off the economic hardship, of course, but even in a social democratic paradise such as Sweden, kids raised in single-parent households do worse than kids raised with both their parents in the home.

March 19, 2015

There’s a deep-seated problem with how we measure the so-called “standard of living”

My family are tired of hearing me say any variation on the expression “the past is a foreign country”, but I ring the changes on that phrase because it at least frames some of the problem we have in trying to comprehend just how much life has changed even within living memory, never mind more than a couple of generations ago. At the Cato Institute, Megan McArdle tries to avoid saying exactly those words, but the sense is still very much the same:

The generation that fought the Civil War paid an incredible price: one in four soldiers never returned home, and one in thirteen of those who did were missing one or more limbs. Were they better off than their parents’ generation? What about the generation that lived through the Great Depression, many of whom graduated into World War II? Does a new refrigerator and a Chevrolet in the driveway make up for decades and lives lost to the march of history? Or for the rapid increase in crime and civic disorder that marked the postwar boom? Then again, what about African Americans, who saw massive improvements in both their personal liberty and their personal income?

We should never pooh-pooh economic progress. As P.J. O’Rourke once remarked, I have one word for people who think that we live in a degenerate era fallen from a blessed past full of bounty and ease, and that word is “dentistry.” On the other hand, we should not reduce standard of living to (appropriately inflation adjusted) GDP numbers either. Living standards are complicated, and the tools we have to measure what is happening to them are almost absurdly crude. I certainly won’t achieve a satisfying measure in this brief essay. But we can, I think, begin to sketch the major ways in which things are better and worse for this generation. Hopefully we can also zero in on what makes the current era feel so deprived, and our distribution of income so worrisome.

My grandfather worked as a grocery boy until he was 26 years old. He married my grandmother on Thanksgiving because that was the only day he could get off. Their honeymoon consisted of a weekend visiting relatives , during which they shared their nuptial bed with their host’s toddler. They came home to a room in his parents’ house—for which they paid monthly rent. Every time I hear that marriage is collapsing because the economy is so bad, I think of their story.

By the standards of today, my grandparents were living in wrenching poverty. Some of this, of course, involves technologies that didn’t exist—as a young couple in the 1930s my grandparents had less access to health care than the most neglected homeless person in modern America, simply because most of the treatments we now have had not yet been invented. That is not the whole story, however. Many of the things we now have already existed; my grandparents simply couldn’t afford them. With some exceptions, such as microwave ovens and computers, most of the modern miracles that transformed 20th century domestic life already existed in some form by 1939. But they were out of the financial reach of most people.

If America today discovered a young couple where the husband had to drop out of high school to help his father clean tons of unsold, rotted produce out of their farm’s silos, and now worked a low-wage, low-skilled job, was living in a single room with no central heating and a single bathroom to share for two families, who had no refrigerator and scrubbed their clothes by hand in a washtub, who had serious conversations in low voices over whether they should replace or mend torn clothes, who had to share a single elderly vehicle or make the eight-mile walk to town … that family would be the subject of a three-part Pulitzer prize winning series on Poverty in America.

But in their time and place, my grandparents were a boring bourgeois couple, struggling to make ends meet as everyone did, but never missing a meal or a Sunday at church. They were excited about the indoor plumbing and electricity which had just been installed on his parents’ farm, and they were not too young to marvel at their amazing good fortune in owning an automobile. In some sense they were incredibly deprived, but there are millions of people in America today who are incomparably better off materially, and yet whose lives strike us (and them) as somehow objectively more difficult.

March 16, 2015

Comparing statistics from different sources

In Forbes, Tim Worstall points out that you need to be careful in using statistics sourced from different organizations or agencies, as they don’t necessarily measure quite the same thing, despite the names being very similar:

There are certain sets of statistics put out (largely by the OECD nations like the US and so on) which we really can believe as saying exactly what is indicated upon the tin.

However, that isn’t the same as saying that we should be willing to just accept all such US or OECD statistical numbers. Take, for example and this is one that I have banged on about for many a year now, The US and other OECD measures of poverty. The standard OECD measure of who is in poverty is below 60% of median income, adjusted for housing costs and household size. This is a measure of inequality, not actual poverty. It is also after all of the things that are done to reduce poverty, benefits, redistribution and all that. The US measure is, again adjusted for household size but not for housing costs, a measure of actual poverty. It is not related to average incomes but to what was low income in the early 1960s updated for inflation. And more significantly, it is before almost all of the things done to try to alleviate poverty. The OECD poverty measure is thus a measure of how much (relative) poverty there is after the things done to reduce poverty and the US standard number is a measure of how much absolute poverty there is before attempts to reduce poverty.

There’s nothing particularly wrong with either measure. But we’ve got to be very careful in acknowledging the difference between the two before we go and do something stupid like directly compare them, US poverty rates against the poverty rates of other OECD countries. Yet we do in fact see such comparisons being made all the time.

Another such little mistake of current interest is the way that we’re continually told that US average wages haven’t risen for decades. And it’s true, in one sense, that they haven’t. But wages aren’t actually what we should be looking at: total compensation from work is. And that’s been rising reasonably nicely over that same time period. The difference is in the benefits that we get over and above our wages from going to work. That health care insurance for example. This is more a matter of manipulation in the presentation of the statistics and if you see someone bleating about “wages” be very careful to check and see whether they are talking about what is of interest, compensation, or about wages which is a sign that they’re trying to mislead.

March 11, 2015

March 3, 2015

“Residual” racism and the breakdown of the African-American family

In Reason, Steve Chapman looks at the tangle of issues still causing problems for African-Americans in the United States:

The breakdown of the black family is a sensitive topic, though it’s not new and it’s not in dispute. President Barack Obama, who grew up with an absent father, often urges black men to be responsible parents.

Nor is there any doubt that African-American children would be better off living with their married parents. Kids who grow up in households headed by a single mother are far more likely than others to be poor, quit school, get pregnant as teens and end up in jail.

[…]

It’s true that whites don’t force blacks to have children out of wedlock. But it’s wrong to suggest that whites bear no responsibility. Poverty is often the result of lack of access to good jobs or any jobs, and discrimination by employers didn’t stop in 1965 — and hasn’t stopped yet.

The impact of drug laws, and the harsher treatment black men get from the criminal justice system, means that many have records that scare employers away. But research indicates that white applicants with criminal records are more likely to get interviews than blacks without criminal records.

A lot of the well-paid blue-collar jobs once abundant in cities have vanished. Moynihan lamented that unemployment had long been much higher for black men than for whites, and the gap is bigger today.

Without decent jobs, these men are not likely to be able to find wives or support families. They are not likely to get married or stay married. If family breakdown causes poverty, poverty also causes family breakdown.

African-Americans often find it hard to leave blighted neighborhoods. They can find themselves steered away from white communities by real estate agents or rejected by landlords. The Urban Institute reports a fact that ought to shock: “The average high-income black person lives in a neighborhood with a higher poverty rate than the average low-income white person” (my emphasis).

February 12, 2015

Petty fines and “public safety” charges fall heaviest on the poor

Megan McArdle on the incredibly regressive way that American municipalities are raising money through fines and other costs imposed disproportionally on the poorest members of the community:

During last summer’s riots in Ferguson, Missouri, reporters began to highlight one reason that relations between the town’s police and its citizens are so fraught: heavy reliance on tickets and fines to cover the town’s budget. The city gets more than $3 million of its $20 million budget from “fines and public safety,” with almost $2 million more coming from various other user fees.

The problem with using your police force as a stealth tax-collection agency is that this functions as a highly regressive tax on people who are already having a hard time of things. Financially marginal people who can’t afford to, say, renew their auto registration get caught up in a cascading nightmare of fees piled upon fees that often ends in bench warrants and nights spent in jail … not for posing a threat to the public order, but for lacking the ready funds to legally operate a motor vehicle in our car-dependent society.

So why do municipalities go this route? The glib answer is “racism and hatred of the poor.” And, quite possibly, that plays a large part, if only in the sense that voters tend to discount costs that fall on other people. But having spent some time plowing through town budgets and reading up on the subject this afternoon, I don’t think that’s the only reason. I suspect that Ferguson is leaning so heavily on fines because it doesn’t have a lot of other terrific options.

QotD: Poverty-stricken Little House on the Prairie

Consider the Little House on the Prairie books, which I’d bet almost every woman in my readership, and many of the men, recalls from their childhoods. I loved those books when I was a kid, which seemed to describe an enchanted world — horses! sleighs! a fire merrily crackling in the fireplace, and children frolicking in the snow all winter, then running barefoot across the prairies! Then I reread them as an adult, as a prelude to my research, and what really strikes you is how incredibly poor these people were. The Ingalls family were in many ways bourgeoisie: educated by the standards of the day, active in community leadership, landowners. And they had nothing.

There’s a scene in one of the books where Laura is excited to get her own tin cup for Christmas, because she previously had to share with her sister. Think about that. No, go into your kitchen and look at your dishes. Then imagine if you had three kids, four plates and three cups, because buying another cup was simply beyond your household budget — because a single cup for your kid to drink out of represented not a few hours of work, but a substantial fraction of your annual earnings, the kind of money you really had to think hard before spending. Then imagine how your five-year-old would feel if they got an orange and a Corelle place setting for Christmas.

There’s a reason old-fashioned kitchens didn’t have cabinets: They didn’t need them. There wasn’t anything to put there.

Imagine if your kids had to spend six months out of the year barefoot because you couldn’t afford for them to wear their shoes year-round. Now, I love being barefoot, and I longed to spend more time that way as a child. But it’s a little different when it’s an option. I walked a mile barefoot on a cold fall day — once. It’s fine for the first few minutes, and then it hurts like hell. Sure, your feet toughen up. But when it’s cold and wet, your feet crack and bleed. As they do if the icy rain soaks through your shoes, and your feet have to stay that way all day because you don’t own anything else to change into. I’m not talking about making sure your kids have a decent pair of shoes to wear to school; I’m talking about not being able to afford to put anything at all on their feet.

Or take the matter of food. There is nothing so romanticized as old-fashioned cookery, lovingly hand-prepared with fresh, 100 percent organic ingredients. If you were a reader of the Little House books, or any number of other series about 19th-century children, then you probably remember the descriptions of luscious meals. When you reread these books, you realize that they were so lovingly described because they were so vanishingly rare. Most of the time, people were eating the same spare food three meals a day: beans, bread or some sort of grain porridge, and a little bit of meat for flavor, heavily preserved in salt. This doesn’t sound romantic and old-fashioned; it sounds tedious and unappetizing. But it was all they could afford, and much of the time, there wasn’t quite enough of that.

These were not the nation’s dispossessed; they were the folks who had capital for seed and farm equipment. There were lots of people in America much poorer than the Ingalls were. Your average middle-class person was, by the standards of today, dead broke and living in abject misery. And don’t tell me that things used to be cheaper back then, because I’m not talking about their cash income or how much money they had stuffed under the mattress. I’m talking about how much they could consume. And the answer is “a lot less of everything”: food, clothes, entertainment. That’s even before we talk about the things that hadn’t yet been invented, such as antibiotics and central heating.

Megan McArdle, “When Bread Bags Weren’t Funny”, Bloomberg View, 2015-01-29.