The first thing I saw was a number of individuals taking photographs of purple carrots and multi-coloured tomatoes to doubtless upload them to Instagram. Customers were shoved out of the way so they could achieve the perfect shot. I can imagine the description that would be added to the images: “At my local market. Buying all organic produce to juice and buying a load of Guatemalan coffee beans to support local farmers. #FoodIsMood”

Carefully navigating the Bugaboos, words leapt out at me from the stalls: “gluten free”, “vegan”, “no added sugar”, “no saturated fats”. It was more like advice from a doctor than things to eat. At the cheese stall I admit I was tempted by the chilli jam accompaniment, as it was described as “rich, tangy tomato with purple shallots and plump sultanas”, but all I needed to do was look at the price — a startling £10 for the small jar with a handwritten label — to decide that the Branston pickle sitting in my store cupboard would do just fine.

An older woman standing by the cheese stall looks as if she is about to pass out. It’s not the heat; rather she has just been informed by the vendor, a young woman with green hair and several face piercings, the price for a piece of Brie and a couple of small goat cheeses. And to add insult to injury, when the customer hands over the £20 to pay she is told, “We only take cards.”

So much for a local, friendly community space. The truth is, these markets are a rip-off, aimed at posturing fools with more money than sense, and food snobs that believe if food isn’t prohibitively expensive for the masses, it’s not good enough to take home and store in their gigantic Smeg fridge.

Julie Bindel, “Mugged by a mud-caked spud”, The Critic, 2022-10-15.

January 21, 2023

QotD: Farmers’ markets are a scam

January 12, 2023

QotD: Describing the CBC to Americans

an audience of any size has yet to be found

So far so CBC, then.

I’m not sure how to describe the CBC to American viewers. The BBC routinely produces content that’s quite entertaining (deliberately, I mean) so it’s not a good analogy. I suppose the best analog would be if NPR and PBS merged and were run by the CPUSA with $20 billion dollars of taxpayer money, and still managed to produce nothing anyone wanted to watch.

Daniel Ream, commenting on David Thompson, “The Giant Testicles Told Me”, DavidThompson, 2022-10-10.

January 5, 2023

The injustices inherent in “asymmetrical multiculturalism”

Ed West traces the start of “asymmetrical multiculturalism” to a 1916 article in The Atlantic by Greenwich Village intellectual Randolph Bourne and traces the damage that resulted from widespread adoption of the policy:

“Asymmetrical multiculturalism” was first coined by demographer Eric Kaufmann in his 2004 book The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America, and later developed in his more recent Whiteshift, in a chapter charting Bourne’s circle, the “first recognisably modern left-liberal open borders movement”.

Kaufmann wrote how asymmetrical multiculturalism “may be precisely dated” to the article where Bourne, “a member of the left-wing modernist Young Intellectuals of Greenwich Village and an avatar of the new bohemian youth culture,” declared “that immigrants should retain their ethnicity while Anglo-Saxons should forsake their uptight heritage for cosmopolitanism.”

Kaufmann suggested that: “Bourne’s desire to see the majority slough off its poisoned heritage while minorities retained theirs blossomed into an ideology that slowly grew in popularity. From the Lost Generation in the 1920s to the Beats in the ’50s, ostensibly ‘exotic’ immigrants and black jazz were held up as expressive and liberating contrasts to a puritanical, square WASPdom. So began the dehumanizing de-culturation of the ethnic majority that has culminated in the sentiment behind, among other things, the viral hashtag #cancelwhitepeople.”

The hope, as John Dewey said of his New England congregationalist denomination around the same time as Bourne, was that America’s Anglo-Saxon core population would “universalise itself out of existence” while leading the world towards universal civilisation.

These ideas certainly didn’t remain in New England or even the United States, as Britain has certainly seen just how destructive they can be recently:

Late last year I wrote about the tragedy of Telford, a town in the English midlands where huge numbers of young girls had been sexually abused. Telford, along with Rotherham in South Yorkshire, had become synonymous with this form of sexual abuse, mostly committed by men of Kashmiri origin against girls who were poor, white and English.

This is the subject of an upcoming GB News documentary by journalist Charlie Peters, and it is quite clear, from all the various reports, that grooming had been allowed to carry on in part because of the different ways the system treats different groups.

Had the races of the perpetrators and victims been reversed, this tragedy would almost certainly be the subject of countless documentaries, plays, films and even official days of commemoration. But it wouldn’t have come to that, because the authorities would have intervened earlier, and more journalists would have been on the case.

Sex crime is perhaps the most explosive source of conflict between communities, and most recently the 2005 Lozells riots began over such a rumour. It is understandable why journalists and reporters were nervous about this subject; less forgivable is the way that, away from the public eye, those in charge signal how gravely they view what happened.

Until Peters revealed the story, Labour had planned to make the former head of Rotherham council its candidate for Rother Valley; this week Peters revealed that one of the councillors named in a report into the town’s failures to deal with the grooming gangs scandal has gone onto become a senior Diversity & Inclusion Manager working for the NHS. Presumably the people who hired Mahroof Hussain knew about his previous job, and still felt that it was appropriate to have him in a “diversity and inclusion” position. Again, were things different, would a Mr Smith whose council had been condemned for its handling of the gang rape of Asian girls have landed that job? The whole thing seems as morbidly comic as Rotherham becoming Children’s Capital of Culture.

Such a clear inconsistency can only exist because of socially-enforced taboos and norms which have developed over race. In Whiteshift, Kaufmann cited sociologist Kai Erikson’s description of norms as the “accumulation of decisions made by the community over a long time” and that “each time the community censures some act of deviance … it sharpens the authority of the violated norm and re-establishes the boundaries of the group”. Every time an individual is punished for violating the anti-racism norm, it strengthens society’s taboo around the subject, to the point where it begins to overwhelm other moral imperatives.

Then there is regalisation, the name for the process “in which adherents of an ideology use moralistic politics to entrench new social norms and punish deviance”, in Kaufmann’s words. This has proved incredibly effective; after paedophilia or sexual abuse, racism is perhaps the most damaging allegation that can be made.

Few people wish to be accused of deviance, which perhaps explains why Peters’s story has received so little coverage in the press this week. Again, were the roles reversed, it’s not wild speculation to suggest that it would feature on the Today programme, seen as clear evidence of racism at the heart of Britain. When the Telford story broke, it did not even feature on the BBC’s Shropshire home page.

November 23, 2022

QotD: Humour and political correctness

As a bumptious adolescent in upstate New York, I stumbled on a British collection of Oscar Wilde’s epigrams in a secondhand bookstore. It was an electrifying revelation, a text that I studied like the bible. What bold, scathing wit, cutting through the sentimental fog of those still rigidly conformist early 1960s, when good girls were expected to simper and defer.

But I never fully understood Wilde’s caustic satire of Victorian philanthropists and humanitarians until the present sludgy tide of political correctness began flooding government, education, and media over the past two decades. Wilde saw the insufferable arrogance and preening sanctimony in his era’s self-appointed guardians of morality.

We’re back to the hypocrisy sweepstakes, where gestures of virtue are as formalized as kabuki. Humor has been assassinated. An off word at work or school will get you booted to the gallows. This is the graveyard of liberalism, whose once noble ideals have turned spectral and vampiric.

Camille Paglia, “Hillary wants Trump to win again”, Spectator USA, 2018-12-04.

October 16, 2022

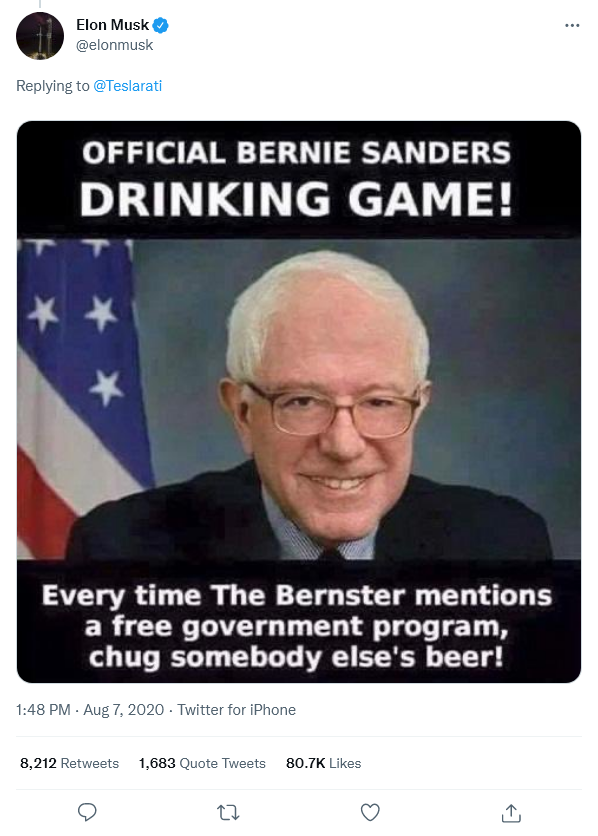

“Musk’s plebeian sense of humor is probably a big part of why the establishment can’t stand him”

Patrick Carroll speculates on why Elon Musk is so disliked by the other rich and powerful folks in his 0.01% demographic:

This isn’t the first time Musk has brought his playful, irreverent, meme-culture spirit to the market. A few years ago he launched his car into space because he thought it would be amusing, and some of his companies now accept Dogecoin as payment.

Musk in general seems rather fun, relatable, and laid back. He doesn’t take himself too seriously, and that’s probably a big part of why people like him.

Another reason he’s so likable is that he doesn’t mind poking fun at politicians, executives, and other “blue-check” elites. To the contrary, he seems to enjoy it.

Examples of Musk mocking the elites abound.

[…]

The question then becomes, how do we combat the insistence on political correctness? How do we push back when moral busybodies insert themselves in matters that are none of their business?

At first, it’s tempting to meet them on their own terms, to politely and logically state our case and request that they leave us alone. And sometimes that can be the right move. But often, a much more effective approach is to do what Elon Musk is doing: become the fool.

Rather than taking the elites seriously, the fool uses wit, humor, and satire to highlight how ridiculous the elites have become. He employs clever mockery and a tactful mischievousness to call the authority of the elites into question. When done well, this approach can be brilliantly effective. There’s a reason joking about politicians was banned in the Soviet Union.

The story of the Weasley twins and Professor Umbridge in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is one of my favorite examples of how mischievousness and mockery can be used to expose and embarrass those who take things too seriously. As you probably know, Umbridge was committed to formality and order, and she imposed stringent limits on fun and games. Now, the Weasley twins — the jesters of Hogwarts, as it were — could have responded with vitriol. They could have written angry letters, signed a petition, and gone through all the proper channels to get her removed. But instead, they threw a party in the middle of exams, making a complete mockery of her seriousness. They gave her the one thing she couldn’t stand: fun. And wasn’t that way more powerful?

If I had to guess, Musk’s plebeian sense of humor is probably a big part of why the establishment can’t stand him. They don’t mind someone who challenges them through the proper channels and in a respectful manner — that’s actually playing into their hand, because it concedes they are deserving of respect in the first place. What they can’t stand is being taken lightly, being teased and ridiculed and ultimately ignored.

Why can’t they stand that? Because our reverence for the elites is actually the source of their power. They win as long as we take them seriously. They lose the moment we don’t.

September 23, 2022

Sarah Hoyt on the Overton Window

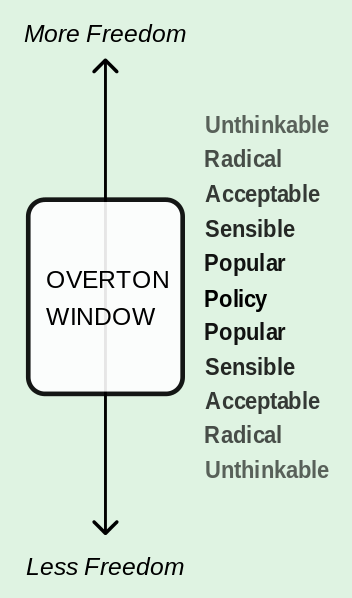

At According to Hoyt, Sarah considers the Overton Window:

Diagram of the “Overton Window”, based on a concept promoted by Joseph P. Overton (1960–2003), former director of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. The term “Overton Window” was coined by colleagues of Joe Overton after his death. In the political theory of the Overton Window, new ideas fall into a range of acceptability to the public, at the edges of which an elected official risks being voted out of office.

Illustration by Hydrargyrum via Wikimedia Commons

The Overton window is not natural to human society. It is the product of the mass-information-media-entertainment era.

No?

Sure, in some villages, or some other places, there are things you can’t see/say. That is usually because someone in that society, be it a village or a nation, is going to get under your nose for saying it. (At one point, you could get arrested in Portugal for shouting “Portugal is a sh*tty country!”)

Having “Unsayable” and “Unthinkable” and “if you say that in public you’ll be shunned” is always a sign of an oppressive society, whether the punishments are physical or mental, beatings or mere shunning.

Having beliefs that are beyond the pale — in fact, the existence of the pale — are a sign of an unhealthy society, one in which a truth is being enforced that is different from reality.

No? Fight me.

Look, yeah, sure, there are things people in all eras didn’t discuss in certain company due to manners or delicacy. One didn’t discuss sexual acts in front of children, not equipped to understand them, in most of the west since the onset of Christianity. One didn’t say certain things in front of elders either. “Gentlemen don’t discuss politics or coitus”. But that was a matter of — in a small gathering, or a confined society — keeping the social gears lubricated, and keeping disagreements at bay. What “couldn’t be said” varied.

However, the Overton window is something else. It is “you can’t report certain things, even if they are true, at the risk of becoming a social pariah”.

It avoids discussions of really important things, like how our kids are being sodomized by public education. Or how welfare really doesn’t contribute to the welfare of anyone. Or how Child Protective Systems is a money-laundering scam, in which kids die. Or how our government-funded science has become all government and almost no science. Etc.

It encourages rape rings like Rotherham, and has most of the black population of the US believe they are more at risk of police shootings than whites, which is plainly not true, but can’t be said, because the media has deemed saying so is “racist” (Somehow.) So people live in fear, rather than knowing they’re not at higher risk than anyone else.

And while speaking of risk, the media, and its control of information and encouragement of shunning dissenters, has led to fear of a “slightly more dangerous” flu, and led to elderly people living their last years in isolation and terror, and also led to our kids being isolated into loss of social function.

Furthermore, the only way to keep the Overton window over a whole country is to enforce strict control over the media, and even social media, and to ruthlessly crush down dissenters, so that everyone appears to agree, leading to shock-rejection of those who manage to break through the wall of government-encouraged-enforced lying.

A wall that they try to keep even when the lies are patently absurd and harmful. (Like the idea anyone who dislikes the Biden reign of terror is a terrorist or insurgent, or for that matter racist.)

The Overton window can suck what I don’t have.

September 21, 2022

Jonathan Kay on cultural appropriation

In Quillette, Jonathan Kay put together “a somewhat lengthy manifesto” on the topic of cultural appropriation in response to a request from Robert Jago who wanted to do an interview with Kay on this issue:

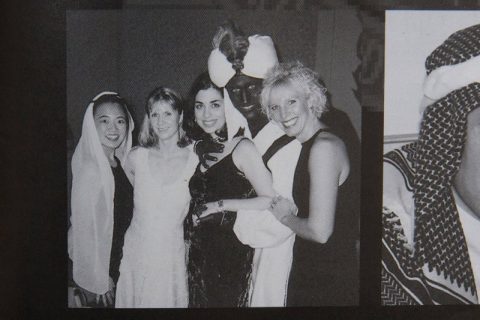

Justin Trudeau (Canada’s most prolific cultural appropriator) with dark makeup on his face, neck and hands at a 2001 “Arabian Nights”-themed party at the West Point Grey Academy, the private school where he taught.

Photo from the West Point Grey Academy yearbook, via Time

“Cultural appropriation” typically gets defined in a way that depends on whether one is defending it or denouncing it. If you’re defending it, you prefer to look at the big picture: Every new kind of art form, literary genre, style of dress, or cuisine typically represents a mix of inherited and borrowed elements. Shakespeare’s sonnets were written in an Iambic pentameter that Chaucer had “appropriated” from the French and Italians. So if Indigenous or African poets want to appropriate it from the English, no one has any basis for complaint. If you define cultural appropriation in this big-picture way, the concept isn’t just permissible. It’s artistically necessary, and indeed inevitable.

But if you’re denouncing cultural appropriation, on the other hand, the argument is more persuasive when your frame of reference is small, local, and community-rooted. I’m thinking of the (white) novelist or film director who passes through a region, and hears some garbled version of folklore that relates to a nearby Indigenous community. The guy thinks, “Oh wow, that’ll make a great novel” (or TV show, movie, etc.), and then makes a mint without consulting (let alone cashing in) the Indigenous community.

So the debate over cultural appropriation is like a lot of debates: It’s really easy to win if you get to define the terms. And since both sides pick definitions that suit them, it can become a dialogue of the deaf.

Indeed, there’s often no dialogue at all. Rather, both sides are apt to retreat into apocalyptic language about, respectively, (a) totalitarian censorship, and (b) white supremacist (cultural) genocide. This is absolutist language that leaves no room for nuance or discussion.

The cultural-universalism side of this dialogue is represented by people like me. I write about every topic under the sun, and so I get my back up when someone tells me that I’ve got to “stay in my lane”. My whole career is built around hopscotching from one idea to the next without worrying (much) about who gets offended. For me, the imposition of rules on what people are allowed to write about isn’t just an annoyance. It’s an existential threat to the creative faculties.

But if you’re on the other end of this — say, you’re a member of a small Indigenous community whose history and folklore have yet to be recorded or celebrated in any definitive form — you don’t care about some white guy in Toronto whining about how he can’t do the equivalent of wearing a sombrero on Cinco de Mayo. A small First Nations community might get only one real shot at telling its story to the world. If that shot gets used up by an outsider who strip-mines the locals’ oral history for a bestseller, that can no doubt feel like existential threat to one’s cultural autonomy. It’s like: “So you took our land, punished us for using our own language, sent our kids to residential schools, and now all we really have left is our culture, and you want to steal that, too?”

There’s this trite expression that often gets trotted out these days: Intent doesn’t matter, only the harm you cause. But of course, intent does matter. And if an author, director, or artist intends to respectfully and accurately include a community’s story in his or her work, then, for me, that’s very much a mark in their favour. That said, I absolutely do not think that this means there is an obligation to “honour” or “uplift” the community in question — let alone express “solidarity” or “allyship” with them. Doing so means you’re writing activist propaganda. What I mean, rather, is that you shouldn’t be intending to mock or belittle whole swathes of humanity.

The problem is that, in Canadian cultural circles at least, this isn’t really the standard that’s applied. I’ve spoken to a number of Canadian writers who, out of the best of intentions, invest their own funds in “sensitivity readers” — a process that can be not only expensive and time-consuming, but also creatively ruinous, since these consultants often are bursting with ideas about how to turn your novel or movie into a specimen of the above-referenced activist propaganda. I know one woman, in particular — a novelist — who appeared before a First Nations tribal council, and got its official permission to include a character in her book whose identity related to their community. But then a community member, someone not even involved with the band leadership, went after the woman and tried to smear her as racist. This is after she’d dotted every I and crossed every T of the sensitivity-reader process.

September 15, 2022

“Presentism is … a disease, a contagion here in America as infectious as the Wuhan flu”

Jeff Minick on the mental attitude that animates so many progressives:

My online dictionary defines presentism as “uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts”. To my surprise, the 40-year-old dictionary on my shelf also contains this eyesore of a word and definition.

To be present, of course, is a generally considered a virtue. It can mean everything from giving ourselves to the job at hand — no one wants a surgeon dreaming of his upcoming vacation to St. Croix while he’s cracking open your chest — to consoling a grieving friend.

But presentism is altogether different. It’s a disease, a contagion here in America as infectious as the Wuhan flu. The latter spreads by way of a virus, the former through ignorance and puffed-up pride.

Presentism is what inspires the afflicted to tear down the statues of such Americans as Washington, Jefferson, and Robert E. Lee for owning slaves without ever once asking why this was so or seeking to discover what these men thought of slavery. Presentism is why the “Little House Books” and some of the early stories by Dr. Seuss are attacked or banned entirely.

Presentism is the reason so many young people can name the Kardashians but can’t tell you the importance of Abraham Lincoln or why we fought in World War II.

Presentism accounts in large measure for our Mount Everest of debt and inflation. Those overseeing our nation’s finances have refused to listen to warnings from the past, even the recent past, about the clear dangers of a government creating trillions of dollars out of the air.

Presentism has led America into overseas adventures that have invariably come to a bad end. Afghanistan, for example, has long been known as the graveyard of empires, a cemetery which includes the tombstones of British and Russian ambitions. By our refusal to heed the lessons of that history and our botched withdrawal from Kabul, we dug our own grave alongside them.

H/T to Kim du Toit for the link.

September 2, 2022

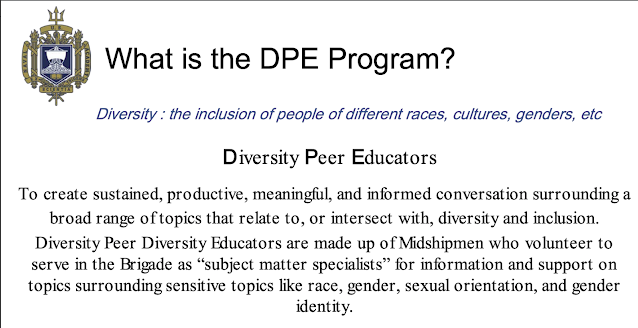

US Navy to get its very own Zampolit cadre

CDR Salamander reports on the latest politically correct doings at the US Naval Academy, which he points out always filter down to the active duty fleet, both good and bad … and I don’t think he considers this particular initiative to be a good one:

The quasi-woke religion as promoted by the CNO provided all the supporting fires they needed and the commissariat decided to make hay while the sun shines.

You know the drill.

Do you want Political Officers, USNA’s own Zampolit? You’ll get them.

Want blue and gold Red Guards? You’re going to have them.

You want red in tooth and claw racism, quotas, and different standards based on self-identified racial groups? You’re going to have more of it.

First let’s pull some nice bits from the governing document; COMDTMIDNINST 1500.5, the “Diversity Education Program” from February of this year. You can read it at the link, or below the pull quotes;

BEHOLD!

1. Purpose. To provide guidance and designate responsibilities for implementation of the Diversity Peer Educator (DPE) Program.

…

b. DPEs support moral development at USNA by facilitating small group conversations that educate and inform midshipmen, faculty, and staff and foster a culture of inclusion across the Yard, resulting in cohesive teams ready to exert maximal performance and win the Naval service’s battles.

I’m not sure you could get more Orwellian … but they’re going to try;

4. Responsibilities

a. USNA Chief Diversity Officer. The Chief Diversity Officer is the final approving authority for all matters pertaining to the DPE Program and will ensure the program is in line with Department of the Navy and Superintendent’s guidance in reference (a).

a. DPE Program Manager. The program manager for DPE is an active-duty officer appointed by the Chief Diversity Officer. Faculty/staff from the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership, the Naval Academy Athletic Association (NAAA), or other cost-centers on the Yard will aid the program manager.

Yes, the football booster organization will “help” the Zampolits. Huh. You see that, yes? Pull that thread …

c. Brigade Dignity and Respect Officer. Reference (c) delineates the roles and responsibilities of the Brigade Dignity and Respect Officer (BDRO) who is accountable for the training, development, and qualification of the DPEs. However, the DPEs are organized and managed by the Midshipman DPE Lead.

d. Midshipmen DPE Lead. A midshipman selected annually by the DPE Program Manager and confirmed by the USNA Chief Diversity Officer. The Midshipmen DPE Lead is typically a First Class Midshipman. Responsibilities include:

(1) Work with the DPE Program Manager to ensure the mission of the program is met.

(2) Provide feedback and keep the DPE Program Manager informed regarding anything that may impact the DPE program.

(3) Serve as the senior DPE, and as the program representative to the BDRO.

(4) Lead and provide guidance to the DPE Midshipmen.

(5) Appoint and manage DPE leads in each battalion, company, varsity athletic team and club sport team.I’ll let you do the math on how many bodies “each” means. That is a lot of Zampolits. I guess MIDN have a lot of extra time.

Again, I want you to ponder the opportunity cost of this across USNA and how it relates to professional development.

September 1, 2022

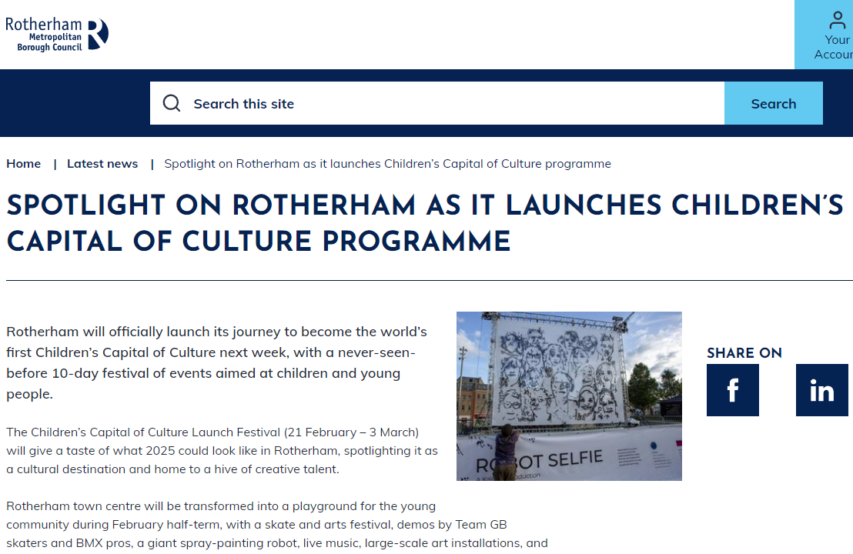

Rotherham Borough Council proudly announces they will be the first “Children’s Capital of Culture”

Honest to God, you can’t parody the real world harder than it parodies itself:

The news that the South Yorkshire market town of Rotherham would be the world’s first “Children’s Capital of Culture” in 2025 has been greeted by many as some kind of sick joke.

Rotherham is at the heart of England’s group-based child sexual exploitation crisis. In 2012, The Times revealed that a confidential 2010 police report had warned that vast numbers of underaged girls were being sexually exploited in South Yorkshire each year by organised networks of men “largely of Pakistani heritage”. South Yorkshire Police and local child-protection agencies were shown to have knowledge of widespread, organised child sexual abuse — but failed to act on this on-the-ground intelligence.

Rotherham borough council, South Yorkshire Police and other public agencies responded by setting up a team of specialists to investigate the reports. In 2013, an independent inquiry spearheaded by Professor Alexis Jay was launched. Her subsequent report into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham, published in 2014, made for awfully grim reading. It found that at least 1,400 children had been subjected to appalling forms of group-based sexual exploitation between 1997 and 2013. The report detailed how girls as young as eleven years of age — either in Year 6 or Year 7 of school — had been intimidated, trafficked, abducted, beaten and raped by men predominantly of Pakistani heritage.

Jay was also deeply critical of the institutional failures that had allowed organised child sexual abuse to flourish in Rotherham. The report concluded that there had been “blatant” collective failures on the part, firstly, of the local council, which consistently downplayed the scale of the problem; and secondly, on the part of South Yorkshire Police, which failed to prioritise investigating the abuse allegations. Indeed, the Jay Report found that the police had “regarded many child victims with contempt”. The inquiry discovered cases involving “children who had been doused in petrol and threatened with being set alight, threatened with guns, made to witness brutally violent rapes and threatened they would be next if they told anyone”. One young person told the inquiry that gang rape was a normal part of growing up in Rotherham. Just let that sink in — groups of adult-male rapists preying on vulnerable girls was normalised in an English minster town.

The Jay Report also took the local authorities to task for elevating concerns about racial sensitivities over the protection of the children in their care — an all-too-familiar element of the nationwide grooming-gangs scandal in England. As the Jay Report put it: “Several [council] staff described their nervousness about identifying the ethnic origins of perpetrators for fear of being thought as racist; others remembered clear direction from their managers not to do so”.

The safety and protection of the most vulnerable girls in society was sacrificed on the altar of state-backed multiculturalism and diversity politics. A recent report published after a series of investigations carried out by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) under “Operation Linden”, found there were “systemic problems” within South Yorkshire Police that meant “like other agencies in Rotherham … it was simply not equipped to deal with the abuse and organised grooming of young girls on the scale we encountered”. South Yorkshire Police recently landed itself in further hot water after it was revealed by The Times that the police force was failing to routinely record the ethnic background of suspected child sexual abusers. For Rotherham, suspect ethnicity was missing for two in three cases.

July 2, 2022

The “preferred pronoun” problem

Jim Treacher is having pronoun problems … not choosing the ones he wants to use or for others to use for him, but the whole “preferred pronoun” imposition on the rest of society to learn, remember, and use properly the bespoke pronoun choices for all the extra, extra-special snowflakes:

Remember when you could just use the pronouns that self-evidently described a person? If you were talking about a fella, you’d say stuff like, “He did this” and “Here’s what I said to him.” Or if you were talking about a lady, you’d say things like, “The 19th Amendment says she can vote now, good for her.” It was a simpler time.

Now pronouns are a frickin’ minefield. You put one little tippy-toe on the wrong pronoun and … BOOM!! A heedless “misgendering” can get you in big trouble. You can get banned from the internet and/or lose your job. For some reason, you’re expected to enable the delusions of any person with trendy mental health issues. It’s not enough for a trans person to call him-, her-, or themselves whatever he, she, or they want. The rest of us are all obligated to go along.

Even if he’s a scumbag criminal like Ezra Miller.

And what’s even worse, this bizarre phenomenon renders news stories about “nonbinary” people almost indecipherable. Just look at this latest story about the ex-Flash actor going around the world being a violent lunatic:

The actor — best known for playing the DC superhero the Flash in several films for Warner Bros. — was set to start filming the studio’s latest entry in the “Harry Potter” franchise, Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore, in London when the shoot was halted on March 15, 2020, due to COVID. In the weeks after, Miller, who identifies as nonbinary and uses “they/them” pronouns, became a regular at bars in Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík, where locals came to know and even befriend them. Many recognized Miller from their earliest breakout movies, 2012’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower and 2011’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, where they played a troubled teen who brought a bow and arrow to school and murdered his classmates.

It’s a grammatical nightmare. “Many recognized Miller from their earliest breakout movies.” Oh, so those Icelanders worked with Miller on those movies? No, you see, “their” is supposed to refer to him.

And this part is just madness: “They played a troubled teen who brought a bow and arrow to school and murdered his classmates.” So it’s not “They murdered their classmates,” because the character he was playing wasn’t nonbinary? What is this gibberish?

Tom Hanks recently said he regrets playing a gay man in Philadelphia because he’s not gay. I always thought that was just called “acting”, but what do I know. If that’s the case, though, why should a nonbinary person be allowed to play a normal person?

June 8, 2022

QotD: Before the (politically correct) Current Era

I have noticed that the authors (or sub-editors) of practically all academic books, or books with intellectual pretensions, now eschew the use of BC and AD, as if to use them were to be either a member of, or an apologist for, the Spanish Inquisition (as popularly, if erroneously, conceived). They have been replaced by the odiously unctuous BCE and CE.

These new initials stand for Before the Common Era and the Common Era: but common to what, and common to whom? Nobody bothers to explain. By strange but happy coincidence, 300 BC turns out to be the same year as 300 BCE, and AD 400 as CE 400, or 400 CE. Why the change, then?

Do those who have promoted it and obeyed its dictates really think that all those sensitive Zoroastrians, who are supposedly so offended by the old style of dating, are also so stupid that they have failed to notice the coincidence and will therefore fail to be offended by it?

The academics, intellectuals and sub-editors of university presses who use the new style evidently believe that the world is populated by people of extreme psychological fragility, and whose self-esteem, which can be shattered by the mere usage of BC and AD, it is their duty to protect.

Thus does condescension and sentimentality unite with megalomania to produce absurd circumlocutions.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Before the current era”, The Critic, 2022-02-09.

March 23, 2022

The New York Times and the “world’s dullest editorial”

Matt Taibbi explains why a milquetoast New York Times editorial got such immense blowback from other legacy media outlets:

The New York Times ran a tepid house editorial in favor of free speech last week. A sober reaction:

One might think running botched WMD reports that got us into the Iraq war or getting a Pulitzer for lauding Stalin’s liquidation of five million kulaks might have constituted worse days — who knew? Pundits, academics, and politicians across the cultural mainstream seemed to agree with Watson, plunging into a days-long freakout over a meh editorial that shows little sign of abating.

“Appalling,” barked J-school professor Jeff Jarvis. “By the time the Times finally realizes what side it’s on, it may be too late,” screeched Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Will Bunch. “The board should retract and resign,” said journalist and former Planet Money of NPR fame founder Adam Davidson. “Toxic, brain-deadening bothsidesism,” railed Dan Froomkin of Press Watch, who went on to demand a retraction and a “mass resignation”. The aforementioned Watson agreed, saying “the NYT should retract this insanity, and replace the entire editorial board.” Not terribly relevant, but amusing still, was the reaction of actor George Takei, who said, “It’s like Bill Maher is now on the New York Times Editorial board.”

The main objection of most of the pilers-on involved the lede of the Times piece, which really was a maladroit piece of writing:

For all the tolerance and enlightenment that modern society claims, Americans are losing hold of a fundamental right as citizens of a free country: the right to speak their minds and voice their opinions in public without fear of being shamed or shunned.

There’s obviously no legal right in America to voice an opinion without being criticized, so this line is indeed an error and an embarrassing one, for a labored-over first line of a major New York Times editorial. On the other hand, a lot of great liberal thinkers decried shaming tactics as utterly opposite to the spirit of free speech, with John Stuart Mill’s warning of a “social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression” being just one example. So, while the Times technically screwed up, cheering shaming and shunning as normal and healthy elements of life in free societies is a pretty weird gotcha. In any case, this bollocksed lede introduced a piece that had been in the works for a while, and came complete with a poll the paper commissioned in conjunction with Siena College.

[…]

This Times editorial is watered down almost the level of a public service announcement written for the Cartoon Network, or maybe a fortune cookie (“Free speech is a process, not a destination. Winning numbers 4, 9, 11, 32, 46 …”). It made the Harper’s letter read like a bin Laden fatwa, but it’s somehow arousing a bigger panic. Its critics view the mention of Republican legislative bans in conjunction with canceling as a monstrous affront, a felony case of both-sidesism. Obviously any implication that there’s any moral comparison between Republicans banning speech by law and Democrats doing it by way of informal backroom deals with unaccountable tech monopolies is unacceptable. Beyond that now, much of the commentariat seems to believe the op-ed page has outlived its usefulness unless it’s engaged in fulsome denunciations of correct targets

March 19, 2022

QotD: The sterility of partisan political argument

For the partisan of deadly nonsense, the person on the other side is neither right nor wrong, since rightness and wrongness are never to be discussed: the person on the other side is merely a jackass, a bigot, ignorant, uninformed, pathetically stupid, Neanderthal, reactionary, bitter, a yokel, a class-traitor, and racist, racist, racist, and racist.

If you are arguing with someone, say, who has a better education than you, a higher I.Q., with perhaps a doctorate in law and a career as a journalist and a published series of books on his resume, that does not matter. The mere fact that he comes to different conclusions than the Party line indicates that he is stupid uneducated Nazi bigot, and a stupid bigoted fascist racist moron.

This is argumentum ad cloaca —— ratiocination via offal. Whatever the loudest donkey laughs loudest at, you take to be untrue. Since that was the way (admit it!) you yourself were convinced, O ye of little mind, it is the first, usually the only means, to which you resort to convince others: the volume and clamor is what matters, not the content.

The reason for the inadequacy of these condemnations, the reason why they are so unimaginative, is because of the paucity of the moral vocabulary of the Left. They do not have words to express outrage, so they sneer and yodel. They are like creature struck dumb, and only able to act out their condemnation by means of antic pantomime.

The more closely they follow Marx, the more impoverished their moral vocabulary becomes. You cannot call someone evil once you accept the proposition that all standards of good and evil are merely genetically-determined group survival behaviors, or merely culturally determined artifacts, or merely ideological superstructures meant to promote class interests. Your concept has lost its referents: it can be used only metaphorically, or ironically.

Likewise, you cannot call someone damned if you don’t believe in damnation. There is no such thing as blasphemy if there is nothing sacred, supernatural, or divine.

Likewise again, you cannot call someone illogical if logic is no longer the standard used to separate self-consistent from self-contradictory statements: because then you would have to argue the merits of the case, and rely on reason, like Adam Smith, rather than on verbal fetishes, like Karl Marx.

Our Progressive detractors have to call the object of their scorn a racist (or a parallel word, such as sexist, lookist, homophobe, capitalist, colorist, agist, whateverist) because that is the only arrow in their quiver. That is the only thing they have to shoot, so they shoot, and do not care how short of the target the dart falls.

John C. Wright, “The Crazy Years and their Empty Moral Vocabulary”, John C. Wright, 2019-02-18.

February 8, 2022

Neil Young and the rebellion of “the Grumpy Old Woke Bros”

Julie Burchill on the (one hopes) last opportunity for elderly, wrinkly 60s and 70s rock stars to virtue signal their protests to a rapidly diminishing body of fans:

For a while now the generation gap has been making a comeback in politics in a way not seen since the youthquake of the 1960s. “Don’t trust anyone over 30” has become “OK Boomer”. Oldsters have been demonised for everything from Brexit to Covid. Personally, at 62, looking at the lives today’s teenagers can expect, I thank my lucky stars that I was young in the 1970s and 80s, when you could say what you liked and go where you wanted. But this dwindling of fun and freedom has as much to do with the stifling nature of woke culture as it does with the other virus.

So I wouldn’t blame teenagers if they were cross. But those doing the most to promote the alienation of young and old aren’t hot-blooded bright young things. They are old men who appear to identify as young, despite sharing the same unsavoury grey whiskers. Of course, if someone with a penis can be a woman, a greybeard can be a teenager. They’re the Grumpy Old Woke Bros.

We can trace this unhappy breed from the then 68-years-young Ian McEwan spluttering at an anti-Brexit rally in 2017: “A gang of angry old men, irritable even in victory, are shaping the future of the country against the inclinations of its youth. By 2019 the country could be in a receptive mood: 2.5million over-18-year-olds, freshly franchised and mostly Remainers; 1.5 million oldsters, mostly Brexiters, freshly in their graves.” Since then the likes of Alexei Sayle, Billy Bragg and Stewart Lee have joined in from the monstrous regiment of woke entertainers, adding Damon Albarn (a youthful 53 – and an OBE, the rebel!) to their rankled ranks last week when he said of Taylor Swift “She doesn’t write her own songs”. (This isn’t the first time Albarn has had beef with young female pop stars. He said of Adele in 2015: “She’s very insecure”, to which she replied “It ended up being one of those ‘Don’t meet your idol’ moments … I was such a big Blur fan growing up. But it was sad, and I regret hanging out with him.”)

Though we think of grumpiness as being an English trait, let’s not forget Neil Young (76) who spat his dummy out last week over sharing Spotify with Joe Rogan. Young is a latecomer to the wonderful world of wokeness, whose welcome to the spotless ranks was somewhat marred by the emergence of a 1985 interview in which he backed Ronald Reagan’s gun control policy and added for good measure, AIDS having recently been discovered, “You go to a supermarket and you see a faggot behind the cash register – you don’t want him to handle your potatoes”.