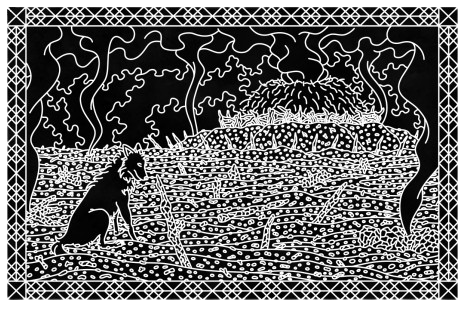

On Substack, Celina101 provides examples of Australian Aborigine behaviour vastly at odds with the progressive belief in the “noble savage” myths:

For decades a rosy and romanticised narrative has prevailed: pre-contact Aboriginal Australia was a utopian paradise, and British colonists the only villains. Yet, the historical record painstakingly chronicled by scholars like William D. Rubinstein and Keith Windschuttle, tells a far more complex, often brutal story. This article examines how politically charged revisionism has whitewashed practices such as infanticide, cannibalism and endemic violence in traditional Aboriginal societies. It also warns that distorting history for ideology does a disservice to all Australians, especially Anglo-Australians who have been bludgeoned over the head with it.

The Noble Savage in Modern Narrative

Many contemporary accounts frame Aboriginals as the ultimate “noble savages”, a peaceful, egalitarian people living in harmony with nature until the arrival of the cruel evil British colonists. Textbooks, media and some activists repeatedly emphasise colonial wrongs while glossing over pre-contact realities. But historians like William D. Rubinstein challenge this rosy picture. Rubinstein bluntly notes that, in contrast to other civilisations that underwent the Neolithic agricultural revolution, Aboriginal society “failed … to advance in nearly all significant areas of the economy and technology” for 65,000 years. In his words, pre-contact Aboriginal life was “65,000 years of murderous, barbaric savagery“. This harsh summary confronts the myth head-on: it implies that life before colonisation was not idyllic, but marked by entrenched violence and brutality.

The danger of the noble-savage myth, Rubinstein argues, is that it inverts history. By idealising and practically lying [about] Aboriginal society, modern narratives often cast settlers as uniquely evil. In one essay he warns that contemporary inquiries (like Victoria’s Yoorrook Commission) are “defined to ascribe all blame to the impact of colonialism, rather than the persisting deficiencies in traditional Aboriginal society“. Ignoring those “gross, often horrifying, shortcomings” in Aboriginal culture, Rubinstein says, can only produce “findings written in the ink of obfuscation and deception“. In short, to truly understand Australia’s past we must examine it dispassionately, acknowledging human failings on all sides, not just one.

Documented Brutalities in Pre-Contact Society

Early observers and anthropologists left abundant evidence that some pre-colonial Aboriginal practices were brutal by modern standards. The selective amnesia about these practices in progressive narratives is striking. For example, infanticide (the intentional killing of newborns) was a widespread means of population control in traditional Aboriginal tribes. University of Michigan anthropologist Aram Yengoyan estimated that infanticide “could have been as high as 40% to 50% of all births … In actuality [it] probably ranged from 15% to 30% of all births“. In practice, this meant large numbers of healthy babies, especially girls, were deliberately killed to cope with limited resources. Babies up to a few years old who fell ill or were deemed surplus were often strangled or left to die. This grim truth is rarely mentioned in schools or media today. According to Rubinstein, it was “ubiquitous” in Australia prior to Western influence.

Several anthropological accounts describe cannibalism of infants and small children in some regions. For instance, an 19th-century observer on the northern coast reported: “Cannibalism is practised by all natives on the north coast … Only children of tender age – up to about two years old, are considered fit subjects for food, and if they fall ill are often strangled by the old men, cooked, and eaten… Parents eat their own children … young and old, [all] partake of it.” (In this passage, even adults were implicated in rare cases: two lost Europeans were reportedly killed and eaten by a tribe in 1874.) Such accounts are shocking, yet they were recorded by colonial-era missionaries and explorers. Today’s activists tend to dismiss or deny them entirely.