Now before I lay into this, fair is fair: Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings had a real habit of having the horses almost always move at the trot or the canter when they ought to have been walking (horses have four “gaits” – patterns of moving – which, in escalating speed are the walk, the trot, the canter and the gallop). Horses can walk or trot for long periods, but canters and gallops can only be maintained in short bursts before the horse wears itself out. So for instance when Théoden leads the Rohirrim from Edoras in Return of the King the horses are walking in the city but by the time they’re in column out of the city the whole column is moving at a canter (interestingly, you can hear the three-beat pattern of the canter in the foley, which is some attention to detail), which is not realistic – they have a long way to go and they won’t be able to maintain this gait the whole way – but fits the forward momentum of the scene. Likewise most of the horses look to be at a canter when his army leaves Dunharrow for Gondor; again this is a bit silly, but on roughly the level of silly of having Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli pursue a band of orcs by jogging for three days and nights without rest.

By contrast [in Rings of Power], the Númenóreans rush to the battle at a full gallop, apparently the whole way or at the very least for hours through the morning. Horses will be vary, but generally two to three miles is the maximum distance most horses can gallop before fatigue sets in (for most horses this distance is going to be shorter), which they’re going to cover in about six minutes. The gallop is a very fast (25-30mph), very short sprint, yet Galadriel has this whole formation at full gallop even before she can see their destination. And I just want to remember here the absurdity that these horsemen do not even know there is a battle to ride to; for all they know this is a basic scouting effort (which might be better accomplished slowly and without wearing down all of the horses). Théoden at least has the excuse that he’s on the clock and knows it!

The way we are then shown the cavalry arriving is very confusing to me. The speed of their arrival makes at least some sense. We have already established that both Arondir and Adar are incompetent commanders so the fact that they have set no scouts or lookouts checks out. Pre-modern and early-modern cavalry could effectively out-ride news of their coming, and so show up unexpectedly in places with very little warning. Not this little warning, mind you – the time from the first sound of hoof-falls (heard by Elves – the orcs evidently hear nothing) to the cavalry deluging the village is just about fifteen seconds; horses move fast but they do not move that fast (at full gallop a horse might cover 150-200 meters in those fifteen seconds and the orcs would absolutely hear them coming before they saw them). But the idea in general that the Númenórean cavalry could appear as if out of nowhere to the orcs checks out – that was one of the major advantages of cavalry operations.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Nitpicks of Power, Part III: That Númenórean Charge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-02-03.

May 23, 2023

QotD: Cavalry operations in Rings of Power versus cavalry operations in history

May 19, 2023

They made a MOVIE about the discovery of Richard III’s remains!!!

Vlogging Through History

Published 16 Sept 2022Here’s a fantastic hour-long breakdown of the entire search and discovery process – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dsTyG…

(more…)

May 16, 2023

QotD: Ah-nuld

Look at all the remakes — not reboots — of Schwarzenegger films since the turn of the century. They have to lard on all kinds of extraneous bullshit to disguise the fact that they’re recycled Arnold movies. There have been upteen Predator movies, for instance … that all focus on the alien (but it’s the humans — specifically, Arnold — who’s the real predator. Dude. Mind … blown). I can’t be the only one who noticed that Liam Neeson’s Taken franchise is just Commando with a different accent … can I? Or that the Bourne Identity films look an awful lot like Total Recall, minus Mars and the three boobs? Then look at all the actual attempted reboots: Conan the Barbarian. Total Recall itself. And the whatever-you-call-thems that are both remakes and reboots of Schwarzenegger movies, where Schwarzenegger is still in them but isn’t the star: the latest Terminator movies, for instance, not to mention also-rans like The Expendables franchise.

The reason you can’t make an “Arnold movie” without Arnold Schwarzenegger, the man, in a starring role isn’t because he’s such an indispensable thespian. It’s because Schwarzenegger doesn’t have an ironic bone in his body. Even when he’s doing comedy (and I think we can all admit, now that he’s in his 70s and effectively long retired, that he could be quite funny), he’s deadly serious. No matter how ludicrous the situation, he’s always 100% in it. No scriptwriter in the 1980s ever felt it necessary to explain how this enormous Austrian bodybuilder ended up being a colonel in the US Special Forces, or a small-town sheriff in Bumfuck, Idaho, or a New York cop, or a CIA agent, or whatever else. He just went with it, and because he did, we did.

In other words, buying a ticket to a Schwarzenegger flick was — like attending a rasslin’ show — an agreement to step outside of ourselves for two hours. We know The Undertaker isn’t a vampire (or whatever), just like we know there’s no possible sequence of events that ever could’ve happened in the real world that would end with an Austrian bodybuilder as a mattress salesman in Minneapolis. So why bother trying to “explain” it? We all agreed, when we bought the ticket, to put “the real world” aside and enter another. In this world, the spectacle’s world, there are vampires who can body slam and bodybuilders who save the world from Satan.

Those are the givens. It doesn’t matter how ludicrous they are, so long as you don’t break your own rules.

Severian, “Rasslin'”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-07-26.

May 13, 2023

QotD: The inherent absurdity of “Canadian content”

Lately some have reminded us of the inherent difficulties in defining Canadian content, especially where a work is the product of several collaborators. Is a movie Canadian by virtue of its actors? Director? Crew? Location? Theme? Even as applied to individuals: Should citizenship be the criterion? Birthplace? Residency? Subject matter?

But the real folly of CanCon is not that it is impractical, or prone to abuse, or even unnecessary, though it is all of those things. It is rather that it is nonsensical at its root, in its very purpose – again, so far as anyone can define it. Is the point, after all, artistic or political? But it cannot be artistic: there is no theory of aesthetics that prefers that Canadian artists should make Canadian art that teaches Canadians how Canadian they are.

It is, rather, a political project: the inculcation of national feeling in the public, for the purpose of creating a political community, separate and distinct from the colossus to the south. Without the Maginot Line of CanCon quotas, it is suggested, we would be overwhelmed: first the artists, then the country.

But note the assumptions built into this emotive appeal: that a separate nationality cannot be maintained without cultural difference; that our cultural differences with the Americans are both sufficient in themselves to justify our statehood and yet so fragile as to be washed away in an instant; that, left to their own choices, Canadians would unhesitatingly choose the products of an incomprehensibly alien culture over their own; and that, by virtue of this diet of foreignism, we would no longer be Who We Are as Canadians. Therefore we must not be left to our own choices.

Which is nonsense, because we would still be Who We Are, even in that hypothetical dystopian future: it might not be Who We Were, but so what? The Who We Are we are now at such pains to preserve is itself vastly different from Who We Were before.

And who, in the end are we? As the comedian Martin Short once put it: “we’re the people who watch a lot of American TV”. The wholesale ingestion of a foreign culture – albeit much of it made by expat Canadians – is an integral part of our distinct national identity, an irony that must forever elude our cultural nationalists.

Andrew Coyne, “The concept of CanCon is pure folly. That’s the problem at the heart of Bill C-11”, The Globe and Mail, 2023-02-08.

May 1, 2023

Doctor Sketchy and the Strange Case of the Syndrome of Doom

Lindybeige

Published 24 Jan 2023I teamed up with the highly-skilled Alasdair Beckett-King and together we threw together this sketch. Can you tell that he went to film school?

(more…)

April 29, 2023

QotD: The problem of war-elephants

The interest in war elephants, at least in the ancient Mediterranean, is caught in a bit of a conundrum. On the one hand, war elephants are undeniably cool, and so feature heavily in pop-culture (especially video games). In Total War games, elephants are shatteringly powerful units that demand specialized responses. In Paradox’s recent Imperator, elephant units are extremely powerful army components. Film gets in on the act too: Alexander (2004) presents Alexander’s final battle at Hydaspes (326) as a debacle, nearing defeat, at the hands of Porus’ elephants (the historical battle was a far more clear-cut victory, according to the sources). So elephants are awesome.

On the other hand, the Romans spend about 200 years (from c. 264 to 46 B.C.) mopping the floor with armies supported by war elephants – Carthaginian, Seleucid, even Roman ones during the civil wars (Thapsus, 46 B.C.). And before someone asks about Hannibal, remember that while the army Hannibal won with in Italy had almost no war elephants (nearly all of them having been lost in the Alps), the army he lost with at Zama had 80 of them. Romans looking back from the later Imperial period seemed to classify war elephants with scythed chariots and other failed Hellenistic “gimmick” weapons (e.g. Q. Curtius Rufus 9.2.19). Arrian (a Roman general writing in the second century A.D.) dismisses the entire branch as obsolete (Arr. Tact. 19.6) and leaves it out of his tactical manual entirely on those grounds.

This negative opinion in turn seeps into the scholarship on the matter. This is in no small part because the study of Indian history (where war elephants remained common) is so under-served in western academia compared to the study of the Greek and Roman world (where the Romans functionally ended the use of war elephants on the conclusion that they were useless). Trautmann, (2015) notes the almost pathetic under-engagement of classical scholars with this fighting system. Scullard’s The elephant in the Greek and Roman World (1974) remains the standard text in English on the topic some 45 years later, despite fairly huge changes in the study of the Achaemenids, Seleucids, and Carthaginians in that period.

All of which actually makes finding good information on war elephants quite difficult – the cheap sensational stuff often fills in the gaps left by a lack of scholarship. The handful of books on the topic vary significantly in terms of seriousness and reliability.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.

April 26, 2023

QotD: The vanishing “entertainer” of yore

As I wrote somewhere in the comments below, we’ve done ourselves a real disservice, culturally, by all but abandoning the profession of “entertainer”. Lennon and McCartney could’ve been the mid 20th century equivalent of Gilbert and Sullivan, writing catchy tunes and performing fun shows, but they got artistic pretensions and we, the public, indulged them, so now everyone who gets in front of a camera — which, in the Social Media age, is pretty much everyone — thinks he has both the right and the duty to educate The Masses.

It was still possible — barely — to be an entertainer as late as the early 2000s. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson was one. Schwarzenegger’s dharma heir, he, along with guys like Jason Statham, made goofy shoot-em-up movies in which improbably muscled men killed a bunch of generic baddies in inventive ways. It’s a lot harder than it looks, since it calls for the lead actor to be fully committed to the role while being fully aware of how silly it all is. The fact that these guys aren’t “actors” in any real sense is no accident.

See also: the only real actor to take on such a role successfully: Liam Neeson, that poor bastard, who uses acting as therapy. (I don’t think it’s an accident that Neeson, too, was an athlete before he was an actor — Wiki just says he “discontinued” boxing at 17, but I read somewhere he was a real contender). Note also that Neeson’s Taken movies have a “real life” hook to them, human trafficking. They’re Schwarzenegger movies, and Neeson acquits himself well in them, but Neeson would fall flat on his face in all-out Arnold-style fantasies — a Conan or a Total Recall. Actors can’t make those movies; only entertainers can [cf. The A-Team, a role Arnold would’ve crushed].

In other words: you can make an “Arnold movie” without Arnold Schwarzenegger, the man, in the lead role, but you absolutely must have an entertainer as a leading man. Nothing could’ve saved the Total Recall “remake”, since it was clearly some other film with a tacked-on subplot to justify using the title, but Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson could’ve saved the Conan remake. It still wouldn’t have been very good — too self-consciously meta and gritty — but as a young guy trying to establish himself, poor ol’ Aquaman wasn’t up to it. He wanted to be a good actor; Arnold, in all his roles, just wanted to make a good movie. Arnold didn’t have to worry about his “performance”, because he was always just being Arnold (this seems to be the secret of Tom Cruise’s success, too). Aquaman had to worry about being taken seriously as an actor.

Severian, “The Entertainer”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-08.

April 13, 2023

Beeching plus 60

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams notes that it’s just past 60 years since one of the most controversial documents the British government published during the latter half of the 20th century: The Beeching Report.

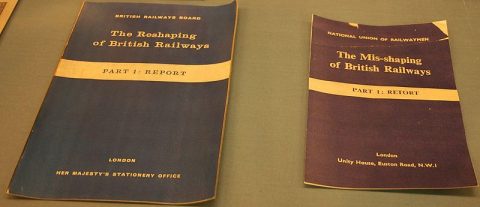

The British Railways Board’s publication The Reshaping of British Railways, Part 1: Report, Beeching’s first report, which famously recommended the closure of many uneconomic British railway lines. Many of the closures were implemented. This copy is displayed at the National Railway Museum in York beside a copy of the National Union of Railwaymen’s published response, The Mis-shaping of British Railways, Part 1: Retort.

Photo by RobertG via Wikimedia Commons.

Wednesday, 27 March 1963 marked the day when a civil servant with a doctorate in physics, seconded from ICI, proudly flourished a report he had written. That man was Dr Richard Beeching, and the result of his recommendations contained in The Reshaping of British Railways are with us to this day.

Beeching identified many unprofitable rail services and suggested the widespread elimination of a huge number of routes. He identified 2,363 stations for closure, along with 6,000 miles of track — a third of the existing network — with the loss of 67,700 jobs. His stated aim was to prune the railway system back into a profitable concern. Behind Beeching, seconded to the newly-established British Railways Board, stood the figure of the publisher-turned-Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan. He knew a thing or two about railways, having been a pre-nationalisation director of the Great Western Railway. It put him in the delightful position of never having to pay for a train ticket.

Macmillan observed from a shareholder’s point of view, “you can pour all in money you want, but you can never make the damned things pay for themselves”. In his view, the railway network and infrastructure of wagon works, tiny branch lines, cottages for signallers, crossings keepers and station masters, with most halts staffed 18 hours a day, amounted to a social service, albeit an expensive one. It had made the prosperity of Victorian Britain possible and was sustaining it still. From nationalisation in 1948, the railways themselves had attempted to make savings, closing 3,000 miles of track and reducing staff from 648,000 to 474,000. That famous Ealing comedy film of 1953, The Titfield Thunderbolt, about a group of villagers trying to keep their branch line operating after British Railways decided to close it, already reflected concern and railway nostalgia.

Britain’s literary and celluloid love affair with iron rails and steam began as long ago as 1905 with the publication of Edith Nesbit’s The Railway Children, a success which peaked when the book was made into a highly successful movie in 1970. Meanwhile, professional sleuths and loafers like Sherlock Holmes, Bulldog Drummond, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot and Bertie Wooster capitalised on the branch line network in their methodology of moving swiftly about pastoral England in their hunts for miscreants. It was the success of The Lady Vanishes, a 1938 mystery thriller set on a continental train, that launched Alfred Hitchcock as a world-class director. David Lean’s Brief Encounter of 1945, based on Noël Coward’s earlier one-act play, Still Life, attached deep romance to station platforms and waiting rooms, reminiscent of so much heartache in the recently fought world war. It is still regarded as one of the greatest of all British-made films. None of this mattered to Beeching, the man who was “Britain’s most-hated civil servant” at his death in 1985, a moniker still used today.

There’s an argument that Beeching was deliberately set up as a patsy for the real villains, Ernest Marples and Harold MacMillan:

The cold, dispassionate Beeching was absolutely the wrong man for the job. As he told the Daily Mirror at the time, “I have no experience of railways, except as a passenger. So, I am not a practical railwayman. But I am a very practical man.” John Betjeman, writing persuasively and eloquently in the Daily Telegraph each week, and later Ian Hislop, hit the right note in observing that Beeching, and all he stood for were technocrats. They “weren’t open to arguments of romantic notions of rural England, or the warp-and-weft of the train in our national identity. They didn’t buy any of that, and went for a straightforward profit and loss approach, from which we are still reeling today”.

However, it has also been argued that Beeching was the unwitting fall-guy for the Minister of Transport of the day, Ernest Marples. He was a self-made businessman who “got things done”, but he retained an air of shadiness about him. Macmillan should have known better. Marples had been managing director of Marples Ridgway, awarded contracts to build the first motorways. When challenged about a conflict of interest, he sold his 80 per cent shareholding to his wife. Elevated to the peerage, Marples fled to Monaco in 1975 to avoid prosecution for tax fraud. So, in some ways, the thing was a stitch-up. Marples directly benefited from the widespread cuts advocated by his subordinate, Beeching. Macmillan had his eye off the ball and was already considering retirement, hastened by an operation for prostate cancer six months after Beeching’s report.

The Prime Minister was astute enough to ensure the press presented the cuts in a positive way, however. From the Cabinet papers of the day, we now know the day before the publication of The Reshaping of British Railways, Beeching’s findings were rewritten to suggest the cuts were the first phase of a co-ordinated national transport policy, with advanced plans to replace the axed rail networks with improved minor roads and local bus services. In reality this was political fantasy (my inner lawyer cautions against more extremist language), for the bus-road subsidy would have cost more than that already paid to the railways. The promise of replacement bus services should have come with a guarantee of remaining in place for at least 10-15 years, because most were withdrawn after two, forcing more motor traffic onto an already inadequate road network.

March 21, 2023

QotD: The elephant as a weapon of war

The pop-culture image of elephants in battle is an awe-inspiring one: massive animals smashing forward through infantry, while men on elephant-back rain missiles down on the hapless enemy. And for once I can surprise you by saying: this isn’t an entirely inaccurate picture. But, as always, we’re also going to introduce some complications into this picture.

Elephants are – all on their own – dangerous animals. Elephants account for several hundred fatalities per year in India even today and even captured elephants are never quite as domesticated as, say, dogs or horses. Whereas a horse is mostly a conveyance in battle (although medieval European knights greatly valued the combativeness of certain breeds of destrier warhorses), a war elephant is a combatant in his own right. When enraged, elephants will gore with tusks and crush with feet, along with using their trunks as weapons to smash, throw or even rip opponents apart (by pinning with the feet). Against other elephants, they will generally lock tusks and attempt to topple their opponent over, with the winner of the contest fatally goring the loser in the exposed belly (Polybius actually describes this behavior, Plb. 5.84.3-4). Dumbo, it turns out, can do some serious damage if prompted.

Elephants were selected for combativeness, which typically meant that the ideal war elephant was an adult male, around 40 years of age (we’ll come back to that). Male elephants enter a state called “musth” once a year, where they show heightened aggressiveness and increases interest in mating. Trautmann (2015) notes a combination of diet, straight up intoxication and training used by war elephant handlers to induce musth in war elephants about to go into battle, because that aggression was prized (given that the signs of musth are observable from the outside, it seems likely to me that these methods worked).

(Note: In the ancient Mediterranean, female elephants seem to have also been used, but it is unclear how often. Cassius Dio (Dio 10.6.48) seems to think some of Pyrrhus’s elephants were female, and my elephant plate shows a mother elephant with her cub, apparently on campaign. It is possible that the difficulty of getting large numbers of elephants outside of India caused the use of female elephants in battle; it’s also possible that our sources and artists – far less familiar with the animals than Indian sources – are themselves confused.)

Thus, whereas I have stressed before that horses are not battering rams, in some sense a good war elephant is. Indeed, sometimes in a very literal sense – as Trautmann notes, “tearing down fortifications” was one of the key functions of Indian war elephants, spelled out in contemporary (to the war elephants) military literature there. A mature Asian elephant male is around 2.75m tall, masses around 4 tons and is much more sturdily built than any horse. Against poorly prepared infantry, a charge of war elephants could simply shock them out of position a lot of the time – though we will deal with some of the psychological aspects there in a moment.

A word on size: film and video-game portrayals often oversize their elephants – sometimes, like the Mumakil of Lord of the Rings, this is clearly a fantasy creature, but often that distinction isn’t made. As notes, male Asian (Indian) elephants are around 2.75m (9ft) tall; modern African bush elephants are larger (c. 10-13ft) but were not used for war. The African elephant which was trained for war was probably either an extinct North African species or the African forest elephant (c. 8ft tall normally) – in either case, ancient sources are clear that African war elephants were smaller than Asian ones.

Thus realistic war elephants should be about 1.5 times the size of an infantryman at the shoulders (assuming an average male height in the premodern world of around 5’6?), but are often shown to be around twice as tall if not even larger. I think this leads into a somewhat unrealistic assumption of how the creatures might function in battle, for people not familiar with how large actual elephants really are.

The elephant as firing platform is also a staple of the pop-culture depiction – often more strongly emphasized because it is easier to film. This is true to their use, but seems to have always been a secondary role from a tactical standpoint – the elephant itself was always more dangerous than anything someone riding it could carry.

There is a social status issue at play here which we’ll come back to […] The driver of the elephant, called a mahout, seems to have typically been a lower-status individual and is left out of a lot of heroic descriptions of elephant-riding (but not driving) aristocrats (much like Egyptian pharaohs tend to erase their chariot drivers when they recount their great victories). Of course, the mahout is the fellow who actually knows how to control the elephant, and was a highly skilled specialist. The elephant is controlled via iron hooks called ankusa. These are no joke – often with a sharp hook and a spear-like point – because elephants selected for combativeness are, unsurprisingly, hard to control. That said, they were not permanent ear-piercings or anything of the sort – the sort of setup in Lord of the Rings is rather unlike the hooks used.

In terms of the riders, we reach a critical distinction. In western media, war elephants almost always appear with great towers on their backs – often very elaborate towers, like those in Lord of the Rings or the film Alexander (2004). Alexander, at least, has it wrong. The howdah – the rigid seat or tower on an elephant’s back – was not an Indian innovation and doesn’t appear in India until the twelfth century (Trautmann supposes, based on the etymology of howdah (originally an Arabic word) that this may have been carried back into India by Islamic armies). Instead, the tower was a Hellenistic idea (called a thorkion in Greek) which post-dates Alexander (but probably not by much).

This is relevant because while the bowmen riding atop elephants in the armies of Alexander’s successors seem to be lower-status military professionals, in India this is where the military aristocrat fights. […] this is a big distinction, so keep it in mind. It also illustrates neatly how the elephant itself was the primary weapon – the society that used these animals the most never really got around to creating a protected firing position on their back because that just wasn’t very important.

In all cases, elephants needed to be supported by infantry (something Alexander (2004) gets right!) Cavalry typically cannot effectively support elephants for reasons we’ll get to in a moment. The standard deployment position for war elephants was directly in front of an infantry force (heavy or light) – when heavy infantry was used, the gap between the two was generally larger, so that the elephants didn’t foul the infantry’s formation.

Infantry support covers for some of the main weaknesses elephants face, keeping the elephants from being isolated and taken down one by one. It also places an effective exploitation force which can take advantage of the havoc the elephants wreck on opposing forces. The “elephants advancing alone and unsupported” formation from Peter Jackson’s Return of the King, by contrast, allows the elephants to be isolated and annihilated (as they subsequently are in the film).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: War Elephants, Part I: Battle Pachyderms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-07-26.

February 20, 2023

Garate Anitua y Cia “El Tigre” – Winchester 1892 Copy

Forgotten Weapons

Published 5 Jun 2016Spain was historically a major center of patent infringement in firearms manufacture because its patent law left open a big loophole: patents were only enforceable if the patent holder actually manufactured their guns in Spain. The major European and American firearms manufacturers were not interested in setting up plants in Spain, and so their patents were not enforced there, leaving Spanish shops and factories legally free to copy them.

One of the more successful copies was the “El Tigre“, a clone of the Winchester 1892 lever action rifle made by Garate Anitua y Cia. Ironically, Garate actually registered their own patent on the design since Winchester hadn’t bothered to, and that patent was enforced, since Garate did make the guns in Spain. Their copy was chambered for the .44-40 Winchester cartridge, known in Spain as the .44 Largo. This made it compatible with many of the revolvers in the country of American, Spanish, and Belgian origin, and thus quite popular with a wide variety of groups. Rural citizen militias and the Guardia Civil both used significant numbers of El Tigre carbines. They were also fairly popular in the United States, as the cost was substantially lower than a true Winchester. Many Hollywood films and shows used them as less expensive prop guns, especially for scenes where guns would be handled roughly.

Despite their competitive cost, the El Tigres were actually quite good guns, and served their owners well.

February 7, 2023

Disney – An Empire In Collapse

The Critical Drinker

Published 6 Feb 2023Disney isn’t looking too healthy these days, with massive financial losses, collapsing stock prices and internal power struggles threatening to tear the House of Mouse apart at the seams. How did this happen? Let’s find out.

(more…)

January 1, 2023

Public Domain Day for 2023

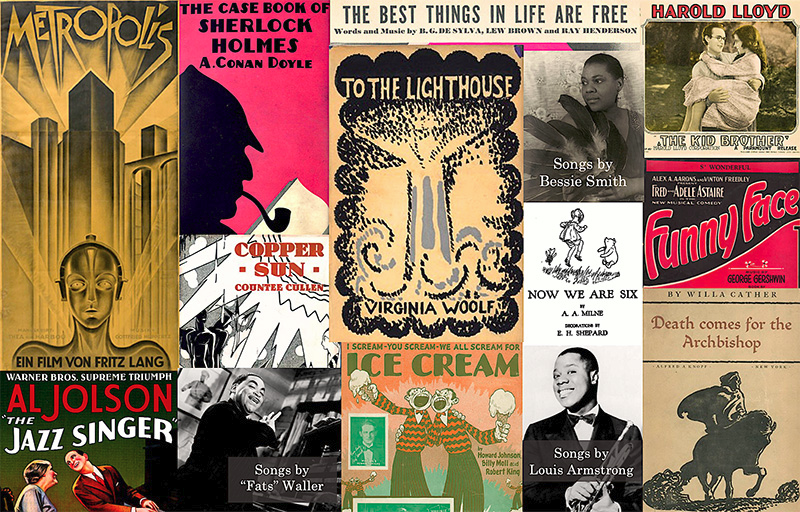

Duke University School of Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain highlights just some of the creative works that have entered into the public domain (in the United States: other countries’ laws may vary substantially) today:

Here are just a few of the works that will be in the US public domain in 2023. They were supposed to go into the public domain in 2003, after being copyrighted for 75 years. But before this could happen, Congress hit a 20-year pause button and extended their copyright term to 95 years. Now the wait is over. (To find more material from 1927, you can visit the Catalogue of Copyright Entries.)

Books:

- Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

- Arthur Conan Doyle, The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes

- Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

- Countee Cullen, Copper Sun

- A. A. Milne, Now We Are Six, illustrated by E. H. Shepard

- Thornton Wilder, The Bridge of San Luis Rey

- Ernest Hemingway, Men Without Women (collection of short stories)

- William Faulkner, Mosquitoes

- Agatha Christie, The Big Four

- Edith Wharton, Twilight Sleep

- Herbert Asbury, The Gangs of New York (the original 1927 publication)

- Franklin W. Dixon (pseudonym), The Tower Treasure (the first Hardy Boys book)

- Hermann Hesse, Der Steppenwolf (in the original German)

- Franz Kafka, Amerika (in the original German)

- Marcel Proust, Le Temps retrouvé (the final installment of In Search of Lost Time, in the original French)

[…]

Movies Entering the Public Domain

- Metropolis (directed by Fritz Lang)

- The Jazz Singer (the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue; directed by Alan Crosland)

- Wings (winner of the first Academy Award for outstanding picture; directed by William A. Wellman)

- Sunrise (directed by F.W. Murnau)

- The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Alfred Hitchcock’s first thriller)

- The King of Kings (directed by Cecil B. DeMille)

- London After Midnight (now a lost film; directed by Tod Browning)

- The Way of All Flesh (now a lost film; directed by Victor Fleming)

- 7th Heaven (inspired the ending of the 2016 film La La Land; directed by Frank Borzage)

- The Kid Brother (starring Harold Lloyd; directed by Ted Wilde)

- The Battle of the Century (starring the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy; directed by Clyde Bruckman)

- Upstream (directed by John Ford)

1927 marked the beginning of the end of the silent film era, with the release of the first full-length feature with synchronized dialogue and sound. Here are the first words spoken in a feature film from The Jazz Singer: “Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothing yet.” Read about the transition from the silent film to the “talkie” era, and the quest to preserve some of the remarkable silent films on this list, here. Please note that while the original footage from these films will be in the public domain, newly added material such as musical accompaniment might still be copyrighted. If a film has been restored or reconstructed, only original and creative additions are eligible for copyright; if a restoration faithfully mimics the preexisting film, it does not contain newly copyrightable material. (Putting skill, labor, and money into a project is not enough to qualify it for copyright. The Supreme Court has made clear that “the sine qua non of copyright is originality.”) In the list above, while some of the titles were not registered for copyright until 1928 or 1929, the original version of the film was published with a 1927 copyright notice, so the copyright expires over that version in 2023.

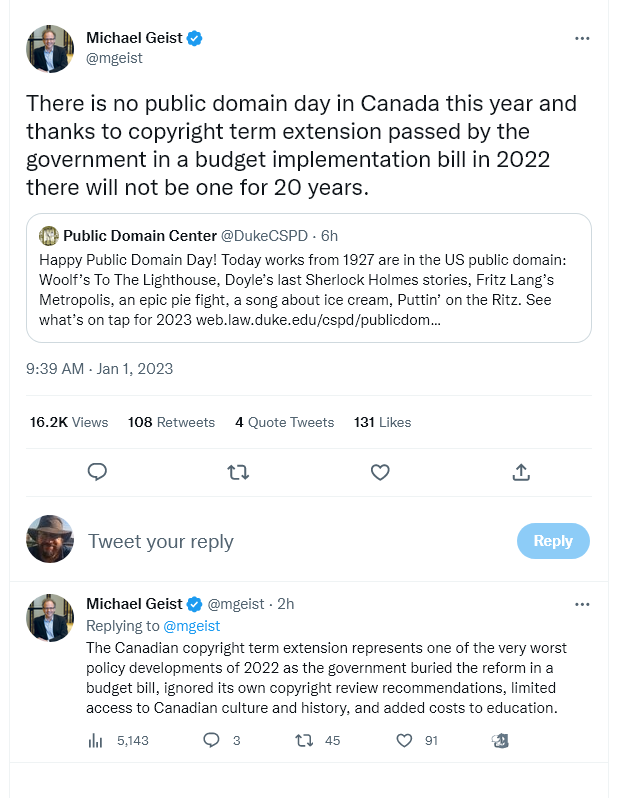

Update: Michael Geist explains why there’s no equivalent Public Domain day for Canada:

December 20, 2022

QotD: Myrna Loy

In the first couple of pages of her 1987 memoir Being and Becoming, Myrna Loy gets down to business. Talking about the sex lives of Hollywood stars such as herself, she tells us that “any business involving so many beautiful and high-strung people working together on such intense and intimate terms is bound to breed an easy promiscuity. God knows I’ve fended off my share of amorous men – attractive, desirable men.”

She goes on to provide a short list: John Barrymore (“just because he felt like a little redhead now and then didn’t incline me to join the club …”), Clark Gable (she shoved him off her back porch one night after he made a pass “and, boy, did he punish me for that!”), Spencer Tracy (“he chased me for years, then sulked adorably when I married someone else …”) and Leslie Howard (despite both of them being married he “wanted to whisk me off to the South Seas, and, believe me, that was tempting …”).

“These days you’re made to feel dull and defensive if you weren’t the Whore of Babylon,” Loy writes. “Well, succumbing isn’t the only interesting aspect of a relationship.”

It’s no surprise that a woman who understands this much was such a natural in screwball comedies, where succumbing is usually held at bay until the last shot, the better to draw out the difficulties, obstacles and improbabilities set up like an obstacle course along the way.

Of the over 120 films she made, most of the first half of her career – largely bit parts, vamps and “exotics” – is forgotten, her reputation based on the fourteen she made with William Powell (six of which were Thin Man pictures), along with titles like The Best Years of Our Lives, The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House and Cheaper by the Dozen.

If she had a type onscreen – and Loy tried hard to avoid becoming a type – she would become Nora Charles, the paragon of wives: supportive but not obsequious, the equal of any spouse, ready with a wisecrack and a bit of fun, and always beautifully turned out. Quite a stretch, she’d admit, for a woman divorced four times, childless and openly dismissive of her domestic skills.

Rick McGinnis, “Do You Take This Woman? Myrna Loy and Third Finger, Left Hand“, Steyn Online, 2022-09-17.

December 15, 2022

QotD: From The Stepford Wives to The Handmaid’s Tale

Hey, did you know The Stepford Wives was published 50 years ago today? Salon does:

Why feminist horror novel The Stepford Wives is still relevant, 50 years on

But before we get to the fisking (I’m running on fumes, y’all; the end of the summer is always the worst time for me), let’s pause for a moment to consider the TV show. You’d think there’d be one, right? Either that, or this is stoyak — The Stepford Wives, coming fall 2022 to Disney Plus. But it doesn’t appear to be. I googled “stepford wives tv show” and got this, which looks trashy enough, but in no way related to the book or movie. There was a remake of the 1970s movie back in 2004, but it bombed.

Odd, no? You’d think that shit would be chick crack — all those Strongk Confidant Wahmens digging into conspiracies and Sticking it to the Man ™. At least, that’s what I thought back in 2004. I thought the casting was dodgy — Kidman was too old (and too glamorous; you really need a pretty-but-not-Hollywood-pretty type) and Matthew Broderick too nebbishy. Nonetheless, I thought the premise would be strong enough to overcome it — oh, you poor, put-upon ladies! But nope.

And then The Handmaid’s Tale happened, as my students would’ve written back in the days, and now I understand why I’m wrong. I should’ve seen it 20 years ago, but better late than never, right? Let’s all have a good laugh at the really obvious thing I missed back in 2004: Strongk, Confidant Wahmens are neither strong nor confident, nor do they want to be either. They want the thinnest veneer of the pretense of the fantasy of those things, delivered to them by a man who comes on like Chad Thundercock, but always somehow has the time to listen to her.

The Handmaid’s Tale, that’s the real chick crack. It’s highbrow bondage porn for the kind of tertiary-educated lady who thinks Fifty Shades of Gray is way too trashy to rent (except, you know, one Girls’ Night with a box of white whine, as a “guilty pleasure”). It gets her all fired up for busting balls at the next partners’ meeting down at the law firm. So empowering!

In The Stepford Wives, book and original movie, the housewives are replaced by robots. The author, Ira Levin, was a guy, and I bet you could tell that just from the one-sentence plot summary. Being replaced by a robot isn’t a “feminist” fear, it’s a male fear. The worry that you’re nothing but a wallet with a criminally underserved dick attached has been pervasive among men since probably the Puritans. It’s a neat trick on Levin’s part, racking up mucho feminist street cred by selling them the #1 male neurosis of the postwar world.

Severian, “SJWs Always Project”, Founding Questions, 2022-08-08.

December 12, 2022

“The reason that Canada’s arts do not resonate with 95% of Canadians is that they are products of socialist realism’

Elizabeth Nickson on the parasitic world of official “Canadian culture” with its gatekeepers, subsidies, and luxury beliefs:

When I say society, I don’t mean the upper reaches of the wealthy. While we do have the very rich in Canada, they are rigorous in their hiddenness because we have the worst lefties on the continent and that is saying something. The safe thing for any wealthy family is give $ to socialists, bow and scrape to the harpies at the CBC and hope they don’t notice your bank balance. Anyway, these dreadful people arrived post WW2 with their hideous Frankfurt School ideas and just preyed on the simplest most innocent well-meaning good white people you could ever imagine, and literally ate, ravenous and braying all the while, the country’s potential.

So the scandal took place among them, or rather the world they created, which is basically a clutch of 150,000 grifters located between Ottawa, Toronto and Quebec City, whose only mission is to divest the government of as much public money as possible. This is particularly true of their defensive line which consists of the arts and journalism. Theirs is a world where no stone is left unsubsidized by taxes on the hidden rich, waitresses at truck stops in Kamloops and anyone who dares to make money unapproved by the CBC. They are, as a former editor swore to me, the gatekeepers. That was before her circulation collapsed by 65%., but no doubt she still believes it.

The arts and media in Canada are constructed entirely for the 5%, consumed by those who live the lush subsidized life — or those who want to — whether in government or in semi-independent corporations or businesses who require government help and “seed” money etc. (There are a hundred terms for the grift.)

Books, if you look at their sales, are tragic. There have been a handful of impressive films, despite the literal billions thrown at filmmakers over the past 20 years. Most of them are catastrophically depressing, the books make you want to cut out your heart with a grapefruit spoon. Painters paint, if you subtract all the hectoring from minor artists, from forced inclusion, some of them are very good. We can create good art. But not with our current curators.

The reason that Canada’s arts do not resonate with 95% of Canadians is that they are products of socialist realism. They describe humans and human life as they either believe it to have been (dark and in need of enlightened beings like themselves) or as they feel it must be in the future (filled with people expressing their oppression and being paid for it). It’s basically fantasy, and no one likes it, watches it, reads it.

The rest of Canada is a centre-right country, a gut-it-out-and-build-it-kind of place. I know that is the exact opposite of the propaganda, but Conservatives win a majority of the votes in every election, yet still only amount to 40%. We have five parties, and four of them are leftie — their platforms are all “more money for us” — but the big party, the one that receives about 30% of the vote is so crafty, so embedded in our vast vast bureaucracy that fixing the game is child’s play. Informed by their Frankfurt School gurus, they have been in power 100 years, with brief Conservative interludes.

We take in about half a million immigrants a year, and most of them are from desperate places. Vote harvesting in those neighborhoods is done by leaders in each immigrant community. These men and women are the strongest, most educated and frankly from the ones I’ve met, thuggish, and through them comes all access to government programs, housing and education. Therefore, when they collect your vote, you know for whom your vote is meant. The thing about immigrants though is that they were coming for the old Canada, not the new Commie police state.

But for now? Easy. No one investigates this. Why not? Our media is subsidized. ALL of it.