It’s difficult to appreciate salt’s historical significance because it’s now so abundant. Societies used to worry about salt supplies — for preparing and preserving food — as a matter of basic survival. Now we use the vast majority of it for making chemicals or chucking on our roads to keep them from getting icy, while many salt-making plants don’t even operate at full capacity. Yet the story of how we came to achieve salt superabundance is a long and complicated one.

In Part I of this series we looked at salt as a kind of general-purpose technology for the improvement of food, as well as a major revenue-raiser for empires — especially when salt-producing coastal areas could dominate salt-less places inland. In Part II we then looked at a couple of places that were all the more interesting for being both coastal and remarkably salt-less: the coast of Bengal and the Baltic Sea. One was to be exploited by the English East India Company, which needlessly propped up a Bengalese salt industry at great human cost. The other, however, was to prove a more contested prize — and ultimately the place that catalysed the emergence of salt superabundance.

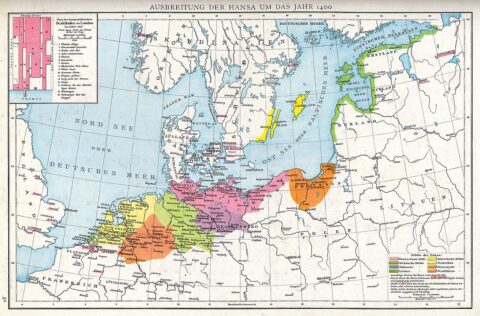

It’s worth a brief recap of where we left the Baltic. Whereas the ocean is on average 3.5% salt, along the Baltic coast it’s at just 0.3% or lower, which would require about twelve times as much time and fuel to produce a given quantity of salt. Although there are a few salt springs near the coast, they were nowhere near large enough to supply the whole region. So from the thirteenth century the Baltic’s salt largely came from the inland salt springs at Lüneburg, supplied via the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg downstream. These two cities had a common interest against the kingdom of Denmark, which controlled the straits between the North and Baltic seas, and created a coalition of trading cities that came to be known as the Hanseatic League. The League resoundingly defeated the Danes in the 1360s and 1430s so that their trade in salt — and the fish they preserved with it — could remain free.

But Lüneburg salt — and by extension the League itself — was soon to face competition.

Lüneburg could simply not keep up with the growth of Baltic demand, as the region’s population became larger and wealthier. And so more and more salt had to come from farther afield, from the Bay of Biscay off France’s western coast, as well as from Setúbal in Portugal and from southern Spain.1 This “bay salt” — originally referring to just the Bay of Bourgneuf, but then extended to the entire Bay of Biscay, and often to all Atlantic solar-evaporated salt — was made by the sun and the wind slowly evaporated the seawater from a series of shallow coastal pools, with the salt forming in coarse, large-grained pieces that were skimmed off the top. Bay salt, however, inevitably ended up mixed with some of the sand and dirt from the bottoms of the pools in which it was held, while the seawater was never filtered, meaning that the salt was often brown, green, grey or black depending on the skill of the person doing the skimming — only the most skilled could create a bay salt that was white. And it often still contained lots of other chemicals found in seawater, like magnesium chloride and sulphate, calcium carbonate and sulphate, potassium chloride and so on, known as bitterns.2

Bay or “black” salt, made with the heat of the sun, was thus of a lower quality than the white salt boiled and refined from inland salt springs or mined as rock. Its dirt discoloured and adulterated food. Its large grains meant it dissolved slowly and unevenly, slowing the rate at which it started to penetrate and preserve the meat and fish — an especially big problem in warmer climates where flesh spoiled quickly. And its bitterns gave it a bitter, gall taste, affecting the texture of the flesh too. Bay salt, thanks to the bitterns, would “draw forth oil and moisture, leading to dryness and hardness”, as well as consuming “the goodness or nutrimental part of the meat, as moisture, gravy, etc.”3 The resulting meat or fish was often left shrunken and tough, while bitterns also slowed the rate at which salt penetrated them too. Bay-salted meat or fish could often end up rotten inside.

But for all these downsides, bay salt required little labour and no fuel. Its main advantage was that it was extremely cheap — as little as half the price of white Lüneburg salt in the Baltic, despite having to be brought from so much farther away.4 Its taste and colour made it unsuitable for use in butter, cheese, or on the table, which was largely reserved for the more expensive white salts. But bay salt’s downsides in terms of preserving meat and fish could be partially offset by simply applying it in excessive quantities — every three barrels of herring, for example, required about a barrel of bay salt to be properly preserved.5

By 1400, Hanseatic merchants were importing bay salt to the Baltic in large and growing quantities, quickly outgrowing the traditional supplies. No other commodity was as necessary or popular: over 70% of the ships arriving to Reval (modern-day Tallinn in Estonia) in the late fifteenth century carried salt, most of it from France. But Hanseatic ships alone proved insufficient to meet the demand. The Danes, Swedes, and even the Hanseatic towns of the eastern Baltic, having so long been under the thumb of Lübeck’s monopoly over salt from Lüneburg, were increasingly happy to accept bay salt brought by ships from the Low Countries — modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands. Indeed, when these interloping Dutch ships were attacked by Lübeck in 1438, most of the rest of the Hanseatic League refused Lübeck’s call to arms. When even the Hanseatic-installed king of Denmark sided with the Dutch as well, Lübeck decided to back down and save face. The 1441 peace treaty allowed the Dutch into the Baltic on equal terms.6 Hanseatic hegemony in the Baltic was officially over.

The Dutch, by the 1440s, had thus gained a share of the carrying trade, exchanging Atlantic bay salt for the Baltic’s grain, timber, and various naval stores like hemp for rope and pitch for caulking. But this was just the beginning.

1. Philippe Dollinger, The German Hansa, trans. D. S. Ault and S. H. Steinberg, The Emergence of International Business, 1200-1800 (Macmillan and Co Ltd, 1970), pp.219-220, 253-4.

2. L. Gittins, “Salt, Salt Making, and the Rise of Cheshire”, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 75, no. 1 (January 2005), pp.139–59; L. G. M. Bass-Becking, “Historical Notes on Salt and Salt-Manufacture”, The Scientific Monthly 32, no. 5 (1931), pp.434–46; A. R. Bridbury, England and the Salt Trade in the Later Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1955), pp.46-52. Incidentally, some historians, like Jonathan I. Israel, Dutch Primacy in World Trade, 1585-1740 (Clarendon Press, 1989) p.223, note occasional reports of French bay salt having been worse than the Portuguese or Spanish due to its high magnesium content, “which imparted an unattractive, blackish colour”. This must be based on a misunderstanding, however, as the salts would have been identical other than in terms of the amount of dirt taken up with the salt from the pans. At certain points in the seventeenth century the French workers skimming the salt must simply have been relatively careless compared to those of Iberia.

3. John Collins, Salt and fishery a discourse thereof (1682), pp.17, 54-5, 66-8.

4. Bridbury, pp.94-7 for estimates.

5. Karl-Gustaf Hildebrand, “Salt and Cloth in Swedish Economic History”, Scandinavian Economic History Review 2, no. 2 (1 July 1954), pp.81, 86, 91.

6. For this section see: Dollinger, pp.194-5, 201, 236, 254, 300.