In industrialized countries, people belong to one institution or another at least until their twenties. After all those years you get used to the idea of belonging to a group of people who all get up in the morning, go to some set of buildings, and do things that they do not, ordinarily, enjoy doing. Belonging to such a group becomes part of your identity: name, age, role, institution. If you have to introduce yourself, or someone else describes you, it will be as something like, John Smith, age 10, a student at such and such elementary school, or John Smith, age 20, a student at such and such college.

When John Smith finishes school he is expected to get a job. And what getting a job seems to mean is joining another institution. Superficially it’s a lot like college. You pick the companies you want to work for and apply to join them. If one likes you, you become a member of this new group. You get up in the morning and go to a new set of buildings, and do things that you do not, ordinarily, enjoy doing. There are a few differences: life is not as much fun, and you get paid, instead of paying, as you did in college. But the similarities feel greater than the differences. John Smith is now John Smith, 22, a software developer at such and such corporation.

In fact John Smith’s life has changed more than he realizes. Socially, a company looks much like college, but the deeper you go into the underlying reality, the more different it gets.

What a company does, and has to do if it wants to continue to exist, is earn money. And the way most companies make money is by creating wealth. Companies can be so specialized that this similarity is concealed, but it is not only manufacturing companies that create wealth. A big component of wealth is location. […] If wealth means what people want, companies that move things also create wealth. Ditto for many other kinds of companies that don’t make anything physical. Nearly all companies exist to do something people want.

And that’s what you do, as well, when you go to work for a company. But here there is another layer that tends to obscure the underlying reality. In a company, the work you do is averaged together with a lot of other people’s. You may not even be aware you’re doing something people want. Your contribution may be indirect. But the company as a whole must be giving people something they want, or they won’t make any money. And if they are paying you x dollars a year, then on average you must be contributing at least x dollars a year worth of work, or the company will be spending more than it makes, and will go out of business.

Someone graduating from college thinks, and is told, that he needs to get a job, as if the important thing were becoming a member of an institution. A more direct way to put it would be: you need to start doing something people want. You don’t need to join a company to do that. All a company is is a group of people working together to do something people want. It’s doing something people want that matters, not joining the group.*

For most people the best plan probably is to go to work for some existing company. But it is a good idea to understand what’s happening when you do this. A job means doing something people want, averaged together with everyone else in that company.

* Many people feel confused and depressed in their early twenties. Life seemed so much more fun in college. Well, of course it was. Don’t be fooled by the surface similarities. You’ve gone from guest to servant. It’s possible to have fun in this new world. Among other things, you now get to go behind the doors that say “authorized personnel only.” But the change is a shock at first, and all the worse if you’re not consciously aware of it.

Paul Graham, “How to Make Wealth”, Paul Graham, 2004-04.

April 17, 2022

QotD: How jobs differ from school

April 3, 2022

King James I and the problem of gold and silver thread in England

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes began to research what appeared to be a minor economic issue that very quickly took over his time going deep down the gold and silver market rabbit hole:

A hammered silver sixpence of James I dated 1603 from the first coinage with a thistle mintmark. Obverse features a right facing crowned bust with the numerals VI behind and the inscription JACOBVS*DG*ANG*SCO*FRA*ET*HIB*REX. The reverse has a shield with the royal arms and the date 1603 above. The reverse inscription is EXERGAT* DEVS*DISSIPENTVR*INIMICI.

FindID 510696 – https://finds.org.uk via Wikimedia Commons

When England’s Parliament met in 1621, it was mainly supposed to vote King James I the funds to fight a war. His daughter’s domain, the Palatinate of the Rhine, had just been invaded, and the European Protestant cause was under grave threat. As I set out two weeks ago, however, the House of Commons had seized the chance to pursue a scandal. Jealous of the Crown’s challenge to their status as local power-brokers, and hoping to embarrass the king’s favourite, the Marquess of Buckingham, MPs opened an investigation into Sir Giles Mompesson’s patent to license inns.

When it came to inns, I argued that the case against Mompesson was flimsy (making me perhaps the only person to have defended him for over four hundred years). He appears to have been a trusted and able bureaucrat, the source of his downfall being his sheer effectiveness. But the flimsiness of the case against him was not enough to stop the political witch-hunt. Next on the list was a project he had administered for making gold and silver thread.

It sounds obscure, and I was fully expecting to write up a short overview of a niche industry that just happened to be thrust into the limelight of 1620s politics. That was a month ago, when I first started drafting this piece. But pulling on the golden thread revealed a desperate, decade-long battle between the City and the Crown, over who would get to control the financial stability of the realm. I’m sorry for the delay in publishing it, but I hope I’ve made it worth the wait.

March 31, 2022

QotD: Nixon’s 1971 gamble to win re-election also tanked the economy for a full decade

[In 1971, economist Herb] Stein was saying aloud what they all knew. Prettifying a political grab by dressing it as an economic rescue was precisely the kind of action against which eminences like Burns warned foreign governments when they made grand speeches abroad. Nixon was indeed now preparing to do what Harold Wilson had done in 1967: disingenuously pretend that devaluing a currency would not affect the consumer. Stimulating the economy in this way might win Nixon the election, but inflation would eventually explode, as Friedman sometimes said, like a closed pot over high heat. Wage and price controls and taxes on imports could make the kind of growth America was accustomed to, the old bonanza, disappear for years, even a decade. True scarcity of key goods might suddenly become the rule. And that was true no matter how many times that cowboy Connally went around bragging about tariffs and telling others that America was “the strongest economy on earth”.

[…]

The 1971 run on American gold also, however, reflected foreigners’ insight. Outsiders knew a tipping point when they saw one. America had moved closer to Michael Harrington’s socialism than even Harrington understood. The United States had locked itself into social spending promises that might never be outgrown. Today, interest in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies serves as a measure of markets’ and individuals’ distrust of the U.S. dollar. In those days there was no Bitcoin, but gold played a similar role. The dollar was the common stock of America, and foreigners used gold to short it.

The disastrous performance of the U.S. economy in the following years proved the foreigners’ 1971 wager correct. To pay for its Great Society commitments, the U.S. government in the next decade found itself forced to set taxes so high that it further suppressed the commercialization of innovation. Products that could have been developed from patents awarded in the 1960s remained on the researchers’ shelves. Today we assume all markets will rebound given a decade. But there was to be no 1970s rebound for the Dow Jones Average. The Dow flirted with the 1,000 level throughout the decade, but did not cross the line definitively until 1982, an astonishingly long period to stagnate, nearly a generation. While markets languished, unemployment for all Americans rose. High prices, high interest rates, and federal budget deficits plagued the nation. “Guns and butter” had proved too expensive, but so indeed had butter alone. The 1960s commitments required spending that, then and down the decades, would be far greater than for Vietnam or most other wars. Those on the far left who had originally pushed for aggressive public-sector expansion had achieved what they sought, to subordinate the private sector. In 1977, Harrington actually titled a new book The Twilight of Capitalism.

Those who had counted on the private sector to sustain prosperity saw they had expected too much. The nation’s confidence evaporated. Indeed, by the late 1970s, President Jimmy Carter felt the need to undertake a national campaign to restore confidence, the kind of campaign Franklin Roosevelt had launched in response to the Great Depression. From being a nation that could afford everything, America morphed into a country that could afford nothing, a place where the president warned citizens to set their living room thermostats to sixty-five in January, or face catastrophe.

In a supreme irony, many of the people who caused the economic damage found themselves mired in the dirty work of reversing what they had wrought. The task of reducing inflation through punishing interest rates fell to Paul Volcker, who as a junior official aided leaders in the 1971 decisions that triggered the 1970s inflation in the first place. Mortgage rates rose to today incredible-sounding levels, over 15 percent. In the 1980s, the same John Connally who as treasury secretary in 1971 pounded on Nixon’s desk for populist measures that ensured an economic quagmire, went bankrupt, a casualty of the mess he had helped to create.

Amity Schlaes, Great Society: A New History, 2019.

March 21, 2022

For some reason, Canadians’ interest in alternative currencies has risen substantially since February

I’m far from alone in taking the Canadian government’s absurd over-reaction to the Freedom Convoy 2022 political protest in February as a reason to be concerned about the Canadian banking system. Until then I’d paid very little attention to alternative currency options like Bitcoin and the like, but I now understand that they may be a key element in future financial planning. At Quillette, Jonathan Kay explains that he realized at the same time he needed to know much more about crypto:

“Bitcoin – from WSJ” by MarkGregory007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

On February 15th, following weeks of anti-vaccine-mandate protests in downtown Ottawa, Justin Trudeau lurched from complete inaction to absurd overreaction by declaring a national emergency. One effect of this was that banks were suddenly authorized to freeze the personal assets of citizens linked with the protests, civil liberties be damned. Around the same time, moreover, hackers acquired and published identifying information associated with thousands of people who’d donated money to the protest movement. Rather than denounce this apparent criminal data breach, many public figures — including Gerald Butts, who’d been Trudeau’s right-hand man before resigning amid scandal in 2019 — actually celebrated this doxxing. Some media outlets even tried to mine the dox information for clickbait before being stung by a public backlash. While I hadn’t donated to the Freedom Convoy movement, I was sufficiently appalled by these developments that I started educating myself about how one might donate to a similar cause without government officials and social-media hyenas exploiting these transactions as a pretext to attack my assets and reputation.

The easiest way to get into the crypto market, I learned, is simply to open an account at an exchange platform such as Coinbase or Wealthsimple. But while they’re easy to use, exchange platforms also generally require clients to supply government-issued ID when they secure their accounts, and transactions are traceable by authorities. To assure myself of real anonymity and theft-protection, my tutor instructed me, a better (if more complex) option is “cold storage”. This is a real physical device — in my case, something called a Ledger — that acts as a personal crypto wallet.

My Ledger (which looks like a large USB key drive) contains the data required to generate the “private keys” (which look like long passwords, though that isn’t quite what they are) that allow me to send my crypto to other people. And that spending can be done only in those moments when the device is connected to the Internet, after which it can be relegated to a drawer or safe (thus the metaphorical concept of “cold storage”). On the other hand, I can receive money even if the Ledger is offline, so long as the sender has my public key, which (unlike a private key) is generally safe to give to others (such as, say, a prospective donor to any charitable cause that I might establish).

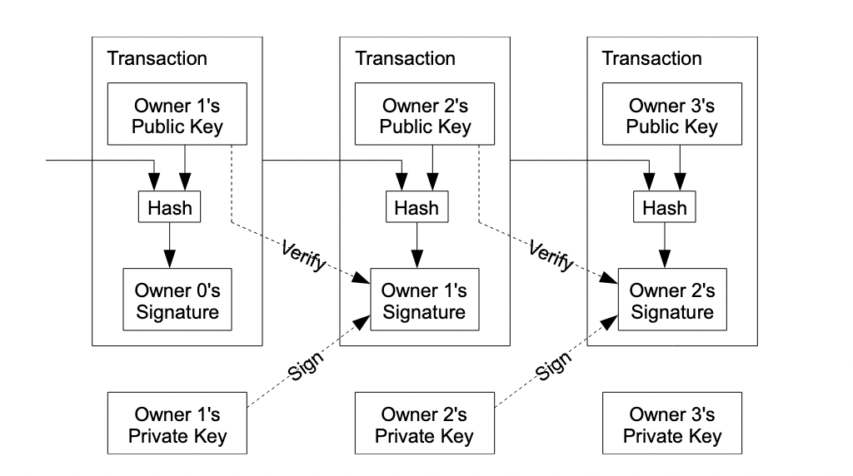

Bitcoin’s basic mechanics were set out in 2009 by the much-mythologized pseudonymous author (or collective) known as “Satoshi Nakamoto”. In a legendary white paper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, Satoshi describes the newly conceived electronic coin as consisting of a chain of digital signatures (a blockchain) that build one upon the next through a mathematical mechanism known as a cryptographic hash function — a one-way function whose output doesn’t expose the original private key to reverse-engineering. So once a bitcoin transaction is recorded and added in verified form to the blockchain by everyone — this being the “public distributed ledger” that bitcoin users are part of — the transaction can’t be erased or reversed (with one important theoretical exception, described later on).

Image contained in Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, demonstrating the use of public and private keys to verify and sign bitcoin transactions.

Of course, you don’t need to understand how this cryptography works to use cryptocurrency. But it is worth getting your head around an important concept that fundamentally separates crypto from conventional assets such as, say, money that sits in a bank account. Your bank account number doesn’t have any value in and of itself: It’s just an institutional convenience that tells you and your bank where your actual money’s been filed (which is why that account number sits in plain sight on every physical check you sign, assuming you still use checks). But in the case of bitcoin, a private key basically is money — in the sense that anyone with access to such a key can spend the associated funds. And so if you lose your private-key information, or it gets stolen by a thief, there’s no 1-800 helpdesk number. It’s gone forever.

January 25, 2022

The fantasy of a modern economy without money

Jon Hersey and Thomas Walker-Werth consider the claim that we’d all be better off without money in a truly modern, egalitarian society:

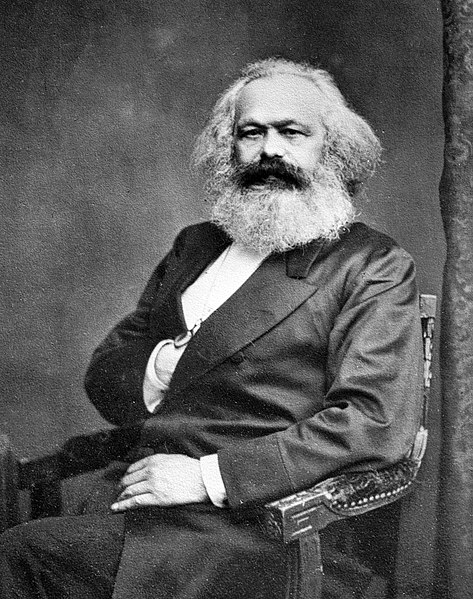

Capitalism, to the extent it has existed, has been incredibly successful at lifting most of humanity out of poverty, incentivizing the creation of incredible, life-enhancing technologies, such as those Maezawa used to make his fortune — not to mention, travel to space. But it’s long had its critics, and he is far from the first to propose a sort of Garden-of-Eden world where everything is plentiful and free. Karl Marx envisioned a similar utopia. Communism, he said, ultimately would bring about a world without money:

In the case of socialised production the money-capital is eliminated. Society distributes labour-power and means of production to the different branches of production. The producers may, for all it matters, receive paper vouchers entitling them to withdraw from the social supplies of consumer goods a quantity corresponding to their labour-time. These vouchers are not money. They do not circulate.

And although “society distributes labour-power” — meaning government planners tell people what to do to ensure that things (such as “free” Ferraris) get made — workers could also all pursue whatever hobbies or occupations strike their fancy. “[I]n communist society,” Marx explained,

where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticize after dinner, just as I have in mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

[…]

Although Marx considered himself a social scientist and economist — and although his ideas are still some of the most widely taught — they aren’t much taught in social science or economics departments, except as foils. That’s because virtually all of Marx’s hypotheses have been debunked. For one, who’s going to build the free Ferraris that Maezawa has dreamed up, never mind tackle more mundane tasks, with no incentive? But for those who don’t find such commonsense thought experiments convincing — or who think, as Marx did, that human nature will somehow mysteriously change — the impracticality of Marx’s moneyless state was demonstrated by what Austrian economists have come to call the calculation problem. Ludwig von Mises once explained the problem as follows:

If a hydroelectric power station is to be built, one must know whether or not this is the most economical way to produce the energy needed. How can he know this if he cannot calculate costs and output?

We may admit that in its initial period a socialist regime could to some extent rely upon the experience of the preceding age of capitalism. But what is to be done later, as conditions change more and more? Of what use could the prices of 1900 be for the director in 1949? And what use can the director in 1980 derive from the knowledge of the prices of 1949?

The paradox of “planning” is that it cannot plan, because of the absence of economic calculation. What is called a planned economy is no economy at all. It is just a system of groping about in the dark.

In short, without prices, people have no relatable, quantifiable means of comparing and contrasting options about how to spend time and capital, which is vital for determining how best to use these naturally scarce resources. “New Scientist magazine reported that in the future, cars could be powered by hazelnuts,” said comedian Jimmy Fallon, in a skit that captures this point hilariously. “That’s encouraging, considering an eight-ounce jar of hazelnuts costs about nine dollars. Yeah, I’ve got an idea for a car that runs on bald eagle heads and Fabergé eggs.”

October 9, 2021

The incredible growth of London after 1550

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers some alternative explanations for London’s spectacular growth beginning in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

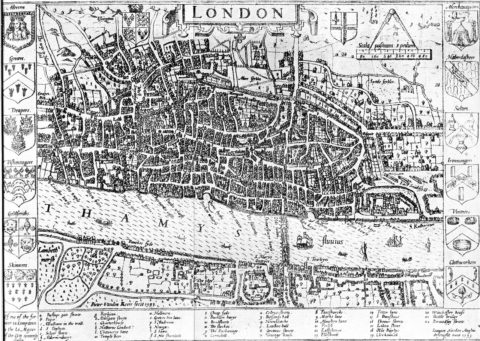

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

As regular readers will know, I’ve lately been obsessed with England’s various economic transformations between 1550 and 1650 — the dramatic eightfold growth of London, in particular, and the fall in the proportion of workers engaged in agriculture despite the growth of the overall population.

As I’ve argued before, I think that the original stimulus for many of these changes was the increased trading range of English overseas merchants. Thanks to advances in navigational techniques, they were able to find new markets and higher prices for their exports, particularly in the Mediterranean and then farter afield. And they were able to buy England’s imports much more cheaply, by going directly to their source. Although the total value of imports rose dramatically — by 150% in just 1600-38 — the value of exports seems to have risen by even more, as there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that for most of the period England had a trade surplus. The supply of money increased, even though Britain had no major gold or silver mines of its own.

The growing commerce was the major spur to London’s growth, with English merchants spending their profits in the city, and ever-cheaper and more varied luxury imports enticing the nobility from their country estates. Altogether, the concentration of people and wealth in London must have resulted in all sorts of spill-over effects to further drive its growth. After the initial push from overseas trade, I suspect that by the late seventeenth century the city was large enough that it was running on its own steam.

But on twitter, economic historian Joe Francis offered a slightly different narrative. Although he agrees that a change to overseas trade was the prime mover, he suggests that the trade itself was too small as a proportion of the economy to account for much of London’s growth. I disagree, for various reasons that I won’t go into now, but Joe brought to my attention various changes on the monetary side. Inspired by the work of Nuno Palma, he suspects that it was not the trade per se, but the fact of an export surplus that was doing the heavy lifting, by increasing the country’s money supply.

An increased money supply should have facilitated England’s internal trades, reducing their costs, and allowing for greater regional specialisation. Joe essentially thinks that I’ve got the mechanism slightly back to front: instead of London’s growing demands having reshaped the countryside, he contends that the specialisation of the entire country is what allowed for the better allocation of economic resources and workers to where they were most productive — a process from which a large city like London quite naturally then emerged.

I have some doubts about whether this process could really have been led from the countryside. The regional specialisation that we see in agriculture, for example, only really starts to become obvious from the 1600s onwards, by which stage London’s population had already begun to balloon from a puny 50,000 in 1550, to 200,000 and rising. I also haven’t found much evidence of other internal trade costs falling. Internal transportation — by packhorse, river, or down the coast — doesn’t seem to have become all that more efficient. Roads and waggon services don’t show much sign of improvement until the eighteenth century, and not many rivers were made more navigable before the mid-seventeenth century either. This is not to say that England’s internal trade didn’t increase. It certainly did, as London sucked in food and fuel in ever larger quantities, and from farther and farther afield. But it still looks like this was led by London demand, rather than by falling costs elsewhere.

Besides, the influxes of bullion from abroad would have all been channelled through London first, along with most of the country’s trade. To the extent that monetisation made a difference to the costs of trade then, this would have made a difference first in the city, before emanating out to its main suppliers, and then outwards. I thus see the Palma narrative as potentially complementary to my own.

June 28, 2021

Pounds, shillings, and pence: a history of English coinage

Lindybeige

Published 18 Dec 2020I talk for a bit the history of English coinage, and the problems of maintaining a good currency. Once or twice I might stray off topic, but I end with an explanation of why the system worked so well.

Picture credits:

40 librae weight

Martinvl, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSceat K series, and others

By Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…William I penny, and Charles II crown

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsBust of Charlemagne

By Beckstet – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Edward VI crown

By CNG – http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?Coi…, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Charles II guinea

Gregory Edmund, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/…, via Wikimedia CommonsSupport me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Buy tat (merch):

https://outloudmerch.com/collections/…Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

My website:

http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

April 18, 2021

QotD: Two centuries on, Ricardo still right

One of David Ricardo’s foundational assertions was the law of one price. That tradeable goods will cost the same, when their transport costs are included, in different places. The insight being that if they weren’t then people would buy in one, sell in the other, thereby equalising prices. A reasonable corollary to this idea is that exchange rates should move based upon purchasing parity or interest rate parity. The second is because people can move their money, just like anything else, to arbitrage between prices – here, the interest rate. The other because, well, that’s what arbitrage will do, equalise those PPP exchange rates. Not wholly, not perfectly, but roughly enough.

Tim Worstall, “Ricardo Still Right 201 Years Later”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-11-01.

July 20, 2020

QotD: Protectionists misunderstand the role of money

A Protectionist is Someone Who … thinks that the ultimate purpose of producing goods and services is to use them to acquire as much money as possible. Unlike a free-trader who understands that the purpose of producing goods and services is to acquire for yourself and your family as many as possible real goods and services to raise as much as possible your standard of living – and who understands that exchanging for money what you directly produce is merely a means of lowering your cost of acquiring in exchange as many as possible goods and services produced by others – the protectionist thinks that the ultimate purpose of producing real goods and services is to use them to acquire as much money as possible.

The Econ 101 teacher typically draws on the white board a diagram of two countries trading with each other. Country A is shown exporting (say) steel to country B in exchange for dollars, and then using those dollars to buy lumber from country B. The Econ 101 teacher informs his or her class that, while these exchanges are mediated by dollars, what ultimately is going on in this diagram is that the people of country A produce steel and send some of that steel to the people of country B because the people of country A want lumber from country B. Likewise, the people of country B produce lumber and send some of it to the people of country A because the people of country B want steel from country A. “The money that you see, class,” explains the Econ 101 teacher, “merely facilitates the exchange of steel for lumber. What’s important here is the getting of steel and of lumber. Money is a tool used by the people of country A to transform some of the steel they produce into lumber that they want to consume. Likewise, money is a tool used by the people of country B to transform some of the lumber they produce into steel that they want to consume.”

The protectionist thinks of this hypothetical two-country exchange entirely differently from the way that the Econ 101 teacher thinks of it. For the protectionist, the people of country A produce steel as a means of getting money; that is the ultimate goal. And the people of country B produce lumber as a means of getting money; that – the getting of money – is the ultimate goal. While for the Econ 101 teacher the two-country diagram that he or she draws is meant to show how money facilitates the ultimate acquisition by the peoples of each country of real goods, for the protectionist the diagram seems to show that the production of real goods is a means of facilitating the ultimate acquisition by the peoples of each country of money.

Don Boudreaux, “A Protectionist is Someone Who…”, Café Hayek, 2018-04-10.

April 14, 2020

QotD: The Edict of Diocletian, 301 AD

The most famous episode of price controls in Roman history was during the reign of Emperor Diocletian (A.D. 244-312). He assumed the throne in Rome in A.D. 284. Almost immediately, Diocletian began to undertake huge and financially expensive government spending projects.

There was a massive increase in the armed forces and military spending; a huge building project was started in the form of a planned new capital for the Roman Empire in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) at the city of Nicomedia; he greatly expanded the Roman bureaucracy; and he instituted forced labor for completion of his public works projects.

[…]

Diocletian also instituted a tax-in-kind; that is, the Roman government would not accept its own worthless, debased money as payment for taxes owed. Since the Roman taxpayers had to meet their tax bills in actual goods, this immobilized the entire population. Many were now bound to the land or a given occupation, so as to assure that they had produced the products that the government demanded as due it at tax collection time. An increasingly rigid economic structure, therefore, was imposed on the whole Roman economy.

But the worst was still to come. In A.D. 301, the famous Edict of Diocletian was passed. The Emperor fixed the prices of grain, beef, eggs, clothing, and other articles sold on the market. He also fixed the wages of those employed in the production of these goods. The penalty imposed for violation of these price and wage controls, that is, for any one caught selling any of these goods at higher than prescribed prices and wages, was death.

Realizing that once these controls were announced, many farmers and manufacturers would lose all incentive to bring their commodities to market at prices set far below what the traders would consider fair market values, Diocletian also prescribed in the Edict that all those who were found to be “hoarding” goods off the market would be severely punished; their goods would be confiscated and they would be put to death.

In the Greek parts of the Roman Empire, archeologists have found the price tables listing the government-mandated prices. They list over 1,000 individual prices and wages set by the law and what the permitted price and wage was to be for each of the commodities, goods, and labor services.

A Roman of this period named Lactanius wrote during this time that Diocletian “… then set himself to regulate the prices of all vendible things. There was much blood shed upon very slight and trifling accounts; and the people brought no more provisions to market, since they could not get a reasonable price for them and this increased the dearth [the scarcity] so much, that at last after many had died by it, the law was set aside.”

Richard M. Ebeling, “How Roman Central Planners Destroyed Their Economy”, Foundation for Economic Education, 2016-10-05.

April 4, 2020

Monetary Policy: The Negative Real Shock Dilemma

Marginal Revolution University

Published 15 Aug 2017Imagine a negative real shock, like an oil crisis, just hit the economy. How should the Fed respond?

Decreasing the money supply will help with inflation, but make growth worse. Increasing the money supply will improve growth, but inflation will climb higher. What’s the Fed to do?!

March 12, 2020

QotD: Cryptocurrency versus cash in a modern economy

The new TV series Ozark has the best explanation of this I’ve seen in popular culture. To paraphrase: Say you have $1 million in cash. What can you actually do with it?

If you try to deposit it in the bank, they will file a report, and you will shortly be explaining to the government where that money came from. Unless you have a good explanation, you will then be desperately trying to hire a lawyer in order to avoid a trip to the pokey.

Nor can you simply buy a house or a car with that cash, which will raise many, many eyebrows at the bank, and then at the government that bank reports to. You basically can’t make any large purchase in cash without raising a lot of questions. This is why drug dealers spend so much effort figuring out how to launder their ill-gotten gains. Unless you can find some way to put the money in a bank without the government getting suspicious, then all you have, in the words of Jason Bateman’s character, is (approximately) “groceries and gas for the rest of your life.”

And that’s dollars, which are indisputably legal tender. Your cryptocurrency will be even harder to spend. Who wants to trade you legal cash for scrip that’s only good for buying on the black market? How do you find that person? What discount will they demand for giving up their cash?

Bitcoin is currently good for transferring money out of failing states like Venezuela, because in those places, the local currency is so worthless that you’re better off trading it for bitcoin, or for that matter, cans of mackerel. But that presumes there are countries elsewhere with stable governments and strong economies where bitcoins can be turned into real goods. If bitcoins become a good way to evade those governments, those governments will ban them, and desperate people will go back to smuggling diamonds and dollars.

Megan McArdle, “Bitcoin Is an Implausible Currency”, Bloomberg View, 2017-12-27.

February 29, 2020

The metallic nickname of Henry VIII

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the rocky investment history for German mining firms in England during the Tudor period:

Cropped image of a Hans Holbein the Younger portrait of King Henry VIII at Petworth House.

Photo by Hans Bernhard via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s an especially interesting case of England’s technological backwardness, given that copper was a material of major strategic importance: a necessary ingredient for the casting of bronze cannon. And it was useful for other industries, especially when mixed with zinc to form brass. Brass was the material of choice for accurate navigational instruments, as well as for ordinary pots and kettles. Most importantly, brass wire was needed for wool cards, used to straighten the fibres ready for spinning into thread. A cheaper and more secure supply of copper might thus potentially make England’s principal export, woollen cloth, even more competitive — if only the English could also work out how to produce brass.

The opportunity to introduce a copper industry appeared in 1560, when German bankers became involved in restoring the gold and silver content of England’s currency. The expensive wars of Henry VIII and Edward VI in the 1540s had prompted debasements of the coinage, to the short-term benefit of the crown, but to the long-term cost of both crown and country. By the end of Henry VIII’s reign, the ostensibly silver coins were actually mostly made of copper (as the coins were used, Henry’s nose on the faces of the coins wore down, revealing the base metal underneath and earning him the nickname Old Coppernose). The debased money continued to circulate for over a decade, driving the good money out of circulation. People preferred to hoard the higher-value currency, to send it abroad to pay for imports, or even to melt it down for the bullion. The weakness of the pound was an especial problem for Thomas Gresham, Queen Elizabeth’s financier, in that government loans from bankers in London and Antwerp had to be repaid in currency that was assessed for its gold and silver content, rather than its face value. Ever short of cash, the government was constantly resorting to such loans, made more expensive by the lack of bullion.

Restoring the currency — calling in the debased coins, melting them down, and then re-minting them at a higher fineness — required expertise that the English did not have. From France, the mint hired Eloy Mestrelle to strike the new coins by machine rather than by hand. (He was likely available because the French authorities suspected him of counterfeiting — the first mention of him in English records is a pardon for forgery, a habit that apparently died hard as he was eventually hanged for the offence). And to do the refining, Gresham hired German metallurgists: Johannes Loner and Daniel Ulstätt got the job, taking payment in the form of the copper they extracted from the debased coinage (along with a little of the silver). It turned out to be a dangerous assignment: some of the copper may have been mixed with arsenic, which was released in fumes during the refining process, thus poisoning the workers. They were prescribed milk, to be drunk from human skulls, for which the government even gave permission to use the traitors’ heads that were displayed on spikes on London Bridge — but to little avail, unfortunately, as some of them still died.

Loner and Ulstätt’s payment in copper appears to be no accident. They were agents of the Augsburg banking firm of Haug, Langnauer and Company, who controlled the major copper mines in Tirol. Having obtained the English government as a client, they now proposed the creation of English copper mines. They saw a chance to use England as a source of cheap copper, with which they could supply the German brass industry. It turns out that the tale of the multinational firm seeking to take advantage of a developing country for its raw materials is an extremely old one: in the 1560s, the developing country was England.

Yet the investment did not quite go according to plan. Although the Germans possessed all of the metallurgical expertise, the English insisted that the endeavour be organised on their own terms: the Company of Mines Royal. Only a third of the company’s twenty-four shares were to be held by the Germans, with the rest purchased by England’s political and mercantile elite: people like William Cecil (the Secretary of State) and the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley (the Queen’s crush). It was an attractive investment, protected from competition by a patent monopoly for mines of gold, silver, copper, and mercury in many of the relevant counties, as well as a life-time exemption for the investors from all taxes raised by parliament (in those days, parliament was pretty much only assembled to legitimise the raising of new taxes).

January 11, 2020

The bubbly 1720s

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at Britain’s volatile financial scene in the 1720s:

William Hogarth – The South Sea Scheme, 1721. In the bottom left corner are Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish figures gambling, while in the middle there is a huge machine, like a merry-go-round, which people are boarding. At the top is a goat, written below which is “Who’l Ride”. The people are scattered around the picture with a sense of disorder, while the progress of the well-dressed people towards the ride in the middle represents the foolishness of the crowd in buying stock in the South Sea Company, which spent more time issuing stock than anything else.

Scanned from The genius of William Hogarth or Hogarth’s Graphical Works via Wikimedia Commons.

Over in France, a Scottish banker named John Law had in the late 1710s overseen an ambitious scheme to reorganise the government’s finances. He ran the Mississippi Company, one of the many companies with monopolies on France’s international trade. His scheme was for the company to acquire all of the other similar monopolies, so that it could have a monopoly on all of the country’s intercontinental trade routes. By 1719, the Mississippi Company had swelled into a Company of the Indies, which in turn had purchased the right to collect French taxes, from which it took took its own cut. In exchange for acquiring these monopolies, Law’s new super-monopoly would buy up the French government’s accumulated war debts, allowing repayment on more generous terms. By allowing the state to borrow more cheaply, the scheme was to be a key plank in improving French military might.

Meanwhile, in Britain, a very similar project was afoot. Following the War of the Spanish Succession, one of the things Britain won from France was the asiento – the monopoly on supplying African slaves to Spain’s colonies in America. The asiento was given to the South Sea Company, which had the monopoly on British trade with South America, and which in 1720 began to follow a scheme similar to Law’s. Given developments in France, it would not do for the British state to be left behind in terms of its capacity to take on more debt for war. Thus, with political support, the South Sea Company began to buy up the government’s debt, persuading its creditors to exchange that debt for increasingly valuable company shares.

In 1720, both schemes came crashing down. In the case of Law’s scheme, he had printed paper currency with which people could buy his company’s shares, but in 1720 discovered he had printed too much. When he prudently tried to devalue the company’s shares to match the quantity of paper notes, the devaluation spun out of control. In the case of the South Sea Company, the causes of the crash were a little more mysterious, perhaps even verging on the mundane. One explanation is that too many wealthy investors simply tried to sell their shares so that they would have ready cash to spend on holidaying in Europe, precipitating a minor fall in the share price which then led to a more widespread panic. Regardless, it did not end well. The company itself continued for many years thereafter — it even got involved with whaling off the coast of Greenland — but the collapse of its share price ended its chance to restructure the government’s debts.

November 27, 2019

QotD: The evolution of markets

It is a settled assumption among most libertarians, classical liberals and English-speaking conservatives that market behaviour is part of human nature. Whether or not we care to make a point of it, we stand with John Locke and, through him, with the men of the Middle Ages and with the Greeks and Romans, in trying to derive what is right from what is natural.

We believe that there is a natural inclination to promote our own welfare and that of our loved ones. We further believe that, given reasonable security of life and property, this inclination will lead to the emergence of a system of voluntary exchange. That is, we will seek to trade the things we have or can create for other things that we regard as of greater value to ourselves.

In doing so, ratios of exchange that we call prices will be revealed. These prices, in turn, will provide general information about what should be produced, in what ways and in what quantities. Furthermore, changes in price will provide information about changes in preferences or in abilities to produce. Custom will set aside one or more goods to serve as money. Institutions will emerge that channel savings into productive investment, that spread risk, and that moderate expected fluctuations in price. Laws will develop to police the transfer of property and performance of contracts.

We believe that market economies emerge spontaneously and are self-regulating and self-sustaining. This is not to say that all market societies will be the same. Their exact shape will depend on the intellectual and moral qualities of the individuals who comprise them. They will reflect pre-existing patterns of trust and honesty and the general cultural and religious values of a people. They will also be more or less distorted by government intervention. But we do say that market behaviour is natural — that, in the absence of extreme government coercion, or extreme disorder, buying and selling to increase our own welfare is what we naturally do.

Sean Gabb, “Market Behaviour in the Ancient World: An Overview of the Debate”, 2008-05.