Marginal Revolution University

Published on 14 Nov 2017Meet the monetarists! This business cycle theory emphasizes the effect of the money supply and the central bank on the economy. Formulated by Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman, it’s a “goldilocks” theory that argues for a steady rate of fairly low inflation to keep the economy on track.

May 24, 2019

Game of Theories: The Monetarists

April 12, 2019

QotD: Money is not wealth

If you want to create wealth, it will help to understand what it is. Wealth is not the same thing as money.* Wealth is as old as human history. Far older, in fact; ants have wealth. Money is a comparatively recent invention.

Wealth is the fundamental thing. Wealth is stuff we want: food, clothes, houses, cars, gadgets, travel to interesting places, and so on. You can have wealth without having money. If you had a magic machine that could on command make you a car or cook you dinner or do your laundry, or do anything else you wanted, you wouldn’t need money. Whereas if you were in the middle of Antarctica, where there is nothing to buy, it wouldn’t matter how much money you had.

Wealth is what you want, not money. But if wealth is the important thing, why does everyone talk about making money? It is a kind of shorthand: money is a way of moving wealth, and in practice they are usually interchangeable. But they are not the same thing, and unless you plan to get rich by counterfeiting, talking about making money can make it harder to understand how to make money.

Money is a side effect of specialization. In a specialized society, most of the things you need, you can’t make for yourself. If you want a potato or a pencil or a place to live, you have to get it from someone else.

How do you get the person who grows the potatoes to give you some? By giving him something he wants in return. But you can’t get very far by trading things directly with the people who need them. If you make violins, and none of the local farmers wants one, how will you eat?

The solution societies find, as they get more specialized, is to make the trade into a two-step process. Instead of trading violins directly for potatoes, you trade violins for, say, silver, which you can then trade again for anything else you need. The intermediate stuff — the medium of exchange — can be anything that’s rare and portable. Historically metals have been the most common, but recently we’ve been using a medium of exchange, called the dollar, that doesn’t physically exist. It works as a medium of exchange, however, because its rarity is guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

The advantage of a medium of exchange is that it makes trade work. The disadvantage is that it tends to obscure what trade really means. People think that what a business does is make money. But money is just the intermediate stage — just a shorthand — for whatever people want. What most businesses really do is make wealth. They do something people want.**

* Until recently even governments sometimes didn’t grasp the distinction between money and wealth. Adam Smith (Wealth of Nations, v:i) mentions several that tried to preserve their “wealth” by forbidding the export of gold or silver. But having more of the medium of exchange would not make a country richer; if you have more money chasing the same amount of material wealth, the only result is higher prices.

** There are many senses of the word “wealth,” not all of them material. I’m not trying to make a deep philosophical point here about which is the true kind. I’m writing about one specific, rather technical sense of the word “wealth.” What people will give you money for. This is an interesting sort of wealth to study, because it is the kind that prevents you from starving. And what people will give you money for depends on them, not you.

When you’re starting a business, it’s easy to slide into thinking that customers want what you do. During the Internet Bubble I talked to a woman who, because she liked the outdoors, was starting an “outdoor portal.” You know what kind of business you should start if you like the outdoors? One to recover data from crashed hard disks.

What’s the connection? None at all. Which is precisely my point. If you want to create wealth (in the narrow technical sense of not starving) then you should be especially skeptical about any plan that centers on things you like doing. That is where your idea of what’s valuable is least likely to coincide with other people’s.

Paul Graham, “How to Make Wealth”, Paul Graham, 2004-04.

March 16, 2019

MMT – Magic Money Theory

Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan explain just why so many progressives are so excited about MMT:

Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, is all the rage in the halls of Congress lately.

To hear the Progressive left tell it, MMT is not unlike a goose that keeps laying golden eggs. All we have to do is pick up all the free money. This is music to politicians’ ears, but Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is singing a decidedly different tune. Said Powell recently on MMT, “The idea that deficits don’t matter for countries that can borrow in their own currency … is just wrong.”

MMT advocates see this as outdated thinking. We can, they claim, spend as much as we want on whatever we want, unencumbered by trivialities like how much we have. But MMT is a bait-and-switch wrapped in a sleight-of-hand. It focuses on debt and dollars rather than resources and products. Debt and dollars are merely tools we use to transfer ownership of resources and products. It’s the resources and products that matter. Shuffling debt and dollars merely changes the ownership of resources and products. It doesn’t create more.

[…]

So here’s the sleight of hand. MMT advocates say that we won’t experience inflation because the U.S. dollar is a reserve currency — foreigners hold lots of U.S. dollars. First, increasing the money supply, other things constant, does create inflation. But when a reserve currency inflates, the pain gets spread around the world instead of being concentrated within one country. In short, MMT advocates believe our government should print money and let foreigners bear some of the inflation pain. Second, there’s no law that says that the U.S. dollar must be a reserve currency. The British Pound was one, but as its value declined, foreigners stopped holding it. Foreigners will stop holding U.S. dollars too as their value declines.

And here’s the bait-and-switch. MMTers say that if inflation does become a problem, the government can simply raise tax rates to soak up excess dollars. In short, the government would print money with one hand, buying whatever it wants and causing inflation. It would then tax with the other, thereby removing dollars from the economy and counteracting the inflation. In the end, all that’s happened is that the government has replaced goods and services that people want with goods and services politicians want.

After a bout of MMT, we might have the same GDP and zero inflation, but what constitutes that GDP would have changed dramatically. Instead of having more cars and houses, we might have more tanks and border walls.

March 5, 2019

Changes in Velocity

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 16 May 2017What happens when aggregate demand shifts because of a change in the velocity of money? You’ll recall from earlier videos that an increase or decrease in velocity means that money is changing hands at a faster or slower rate.

Changes in velocity are temporary, but they can still cause business fluctuations. For instance, say that consumption growth slows as consumers become pessimistic about the economy.

In fact, we saw this play out in 2008, when workers and consumers became afraid that they might lose their jobs during the Great Recession. This fear drove them to cut back on their spending in the short run. But, since changes in velocity are temporary, this fear receded as time passed and the economy began to recover.

Dive into this video to learn more about what causes shifts in the aggregate demand curve.

January 20, 2019

The Short-Run Aggregate Supply Curve

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 9 May 2017In this video, we explore how rapid shocks to the aggregate demand curve can cause business fluctuations.

As the government increases the money supply, aggregate demand also increases. A baker, for example, may see greater demand for her baked goods, resulting in her hiring more workers. In this sense, real output increases along with money supply.

But what happens when the baker and her workers begin to spend this extra money? Prices begin to rise. The baker will also increase the price of her baked goods to match the price increases elsewhere in the economy. As prices increase, workers demand higher wages to be able to afford goods at a higher price.

In this example, the increase in money supply initially increased nominal and real wages for the baker and her employees, but as prices begin to rise, real wages begin to fall, and workers can afford less. Overtime, the demand for the baker’s goods will fall to pre-spending levels.

The takeaway? An increase in spending can increase output and growth in the short run, but not in the long run. To model this scenario, this video will show you how to draw a short-run aggregate supply curve. Let’s get started!

November 23, 2018

The Aggregate Demand Curve

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 18 Apr 2017This wk: Put your quantity theory of money knowledge to use in understanding the aggregate demand curve.

Next wk: Use your knowledge of the AD curve to dig into the long-run aggregate supply curve.

The aggregate demand-aggregate supply model, or AD-AS model, can help us understand business fluctuations. In this video, we’ll focus on the aggregate demand curve.

The aggregate demand curve shows us all of the possible combinations of inflation and real growth that are consistent with a specified rate of spending growth. The dynamic quantity theory of money (M + v = P + Y), which we covered in a previous video, can help us understand this concept.

We’ll walk you through an example by plotting inflation on the y-axis and real growth on the x-axis — helping us draw an aggregate demand curve!

Next week, we’ll combine our new knowledge on the AD curve with the long-run aggregate supply curve. Stay tuned!

October 13, 2018

Why Governments Create Inflation

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 14 Feb 2017Inflation can carry with it quite a few costs. But some governments, like Zimbabwe under President Robert Mugabe in the early 2000s, will go out of their to way to create inflation. Why?

Well, in the Zimbabwe example, the government printed the money and used it to buy goods and services. The ensuing hyperinflation acted as a tax that transferred wealth from the citizens to the government.

However, this is a fairly uncommon reason. Inflation doesn’t make for a good tax and it’s a last resort for desperate governments that are otherwise unable to raise funds.

There are other benefits to inflation that would make governments want to create it. In the short run, inflation can actually boost economic output. However, as we’ve previously covered, an increase in the money supply leads to an equal increase in prices in the long run.

If there’s a recession, governments might create inflation to spur productivity and ease the economic downturn. However, this type of inflationary boosting can be abused. Long-term boosting causes people to simply expect and prepare for it.

Reducing inflation is also costly. If the process is reversed and the growth in the money supply decreases, we get disinflation. Unemployment will likely increase in the short run and an economy can go through a recession. But in the long run, prices will adjust as well.

Inflation can be a neat trick for governments to boost productivity in an economy. But it can easily get out of hand and has even been likened to a drug. Once you start, you need more and more. And stopping is awfully painful as the economy shrinks.

This concludes our section on Inflation and the Quantity Theory of Money. Up next in Principles of Macroeconomics, we’ll be digging into Business Fluctuations.

September 6, 2018

Costs of Inflation: Price Confusion and Money Illusion

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 2 Feb 2017The inflation rate can be somewhat volatile and unpredictable. For example, let’s take the period between 1964 and 1983 in the U.S. The inflation rate jumped around from 1.3% in 1964 to 5.9% in 1970, and all the way up to 14% in in 1980, before dipping back down to 3% in 1983. These dramatic changes, though still fairly mild in the realm of inflation, caught people off-guard.

Peru’s inflation rates in the late 1980s through the early 1990s were on even more of a rollercoaster. Clocking in at 77% in 1986, its inflation rate was already quite high. But by 1990, it had jumped to 7,500%, only to fall to 73% a mere two years later.

High and volatile inflation rates can wreak havoc on the price system where prices act as signals. If the price of oil rises, it signals scarcity of that product and allows consumers to search for alternatives. But with high and volatile inflation, there’s noise interfering with this price signal. Is oil really more scarce? Or are prices simply rising? This leads to price confusion – people are unsure of what to do and the price system is less effective at coordinating market activity.

Money illusion is another problem associated with inflation. You’ve likely experienced this yourself. Think of something that you’ve noticed has gotten more expensive over the course of your lifetime, such as a ticket to the movies. Is it really that going out the movies has become a pricier activity, or is it the result of inflation? It’s difficult for us to make all of the calculations to accurately compare rising costs. This is known as “money illusion” – or when we mistake a change in the nominal price with a change in the real price.

Inflation, especially when it’s high and volatile, can result in some costly problems for everyone. Next up, we’ll look at how it redistributes wealth and can break down financial intermediation.

August 20, 2018

Causes of Inflation

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 24 Jan 2017In the last video, we learned the quantity theory of money and its corresponding identity equation: M x V = P x Y

For a quick refresher:

•M is the money supply.

•V is the velocity of money.

•P is the price level.

•And Y is the real GDP.

In this video, we’re rewriting the equation slightly to divide both sides by Y and explore the causes behind inflation. What we discover is that a change in P has three possible causes – changes in M, V, or Y.

You probably know that prices can change a lot, even over a short period of time.

Y, or real GDP, tends to change rather slowly. Even a seemingly small jump or fall in Y, such as 10% in a year, would signal astonishing economic growth or a great depression. Y probably isn’t our usual culprit for inflation.

V, or the velocity of money, also tends to be rather stable for an economy. The average dollar in the United States has a velocity of about 7. That may fall or rise slightly, but not enough to influence prices.

That leaves us with M. Changes in the money supply are the driving factor behind inflation. Put simply, when more money chases the same amount of goods and services, prices must rise.

Can we put this theory to the test? Let’s look at some real-world examples and see if the quantity theory of money holds up.

In Peru in 1990, hyperinflation came into full swing. If we track the growth rate of the money supply to the growth rate of prices, we can see that they align almost perfectly on a graph with both clocking in around 6,000% that year.

If we plot the growth rates of the money supply along with the growth rates of prices for a many countries over a long stretch of time, we can see the same relationship.

We’ll wrap-up the causes of inflation with three principles to keep in mind as we continue exploring this topic:

•Money is neutral in the long run: a doubling of the money supply will eventually mean a doubling of the price level.

•“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomena.” – Milton Friedman

•Central banks have significant control over a nation’s money supply and inflation rate.

August 9, 2018

Quantity Theory of Money

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 17 Jan 2017The quantity theory of money is an important tool for thinking about issues in macroeconomics.

The equation for the quantity theory of money is: M x V = P x Y

What do the variables represent?

M is fairly straightforward – it’s the money supply in an economy.

A typical dollar bill can go on a long journey during the course of a single year. It can be spent in exchange for goods and services numerous times. In the quantity theory of money, how many times an average dollar is exchanged is its velocity, or V.

The price level of goods and services in an economy is represented by P.

Finally, Y is all of the finished goods and services sold in an economy – aka real GDP. When you multiply P x Y, the result is nominal GDP.

Actually, when you multiply M x V (the money supply times the velocity of money), you also get nominal GDP. M x V is equal to P x Y by definition – it’s an identity equation.

You can think about the two sides of the equation like this: the left (M x V) covers the actions of consumers while the right (P x Y) covers the actions of producers. Since everything that is sold is bought by someone, these two sides will remain equal.

Up next, we’ll use the quantity theory of money to discuss the causes of inflation.

July 20, 2018

Fiat currency and the impact of cryptocurrencies

At Catallaxy Files, Sinclair Davidson explains some of the advantages and disadvantages of both fiat (government-issued) and private currency:

As George Selgin, Larry White and others have shown, many historical societies had systems of private money — free banking — where the institution of money was provided by the market.

But for the most part, private monies have been displaced by fiat currencies, and live on as a historical curiosity.

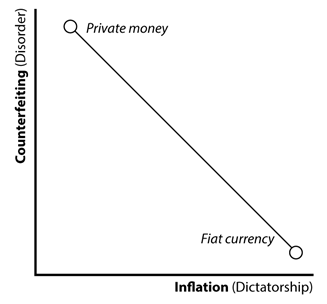

We can explain this with an ‘institutional possibility frontier’; a framework developed first by Harvard economist Andrei Shleifer and his various co-authors. Shleifer and colleagues array social institutions according to how they trade-off the risks of disorder (that is, private fraud and theft) against the risk of dictatorship (that is, government expropriation, oppression, etc.) along the frontier.

As the graph shows, for money these risks are counterfeiting (disorder) and unexpected inflation (dictatorship). The free banking era taught us that private currencies are vulnerable to counterfeiting, but due to competitive market pressure, minimise the risk of inflation.

By contrast, fiat currencies are less susceptible to counterfeiting. Governments are a trusted third party that aggressively prosecutes currency fraud. The tradeoff though is that governments get the power of inflating the currency.

The fact that fiat currencies seem to be widely preferred in the world isn’t only because of fiat currency laws. It’s that citizens seem to be relatively happy with this tradeoff. They would prefer to take the risk of inflation over the risk of counterfeiting.

One reason why this might be the case is because they can both diversify and hedge against the likelihood of inflation by holding assets such as gold, or foreign currency.

The dictatorship costs of fiat currency are apparently not as high as ‘hard money’ theorists imagine.

Introducing cryptocurrencies

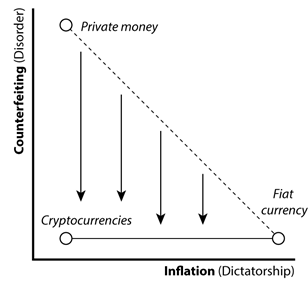

Cryptocurrencies significantly change this dynamic.

Cryptocurrencies are a form of private money that substantially, if not entirely, eliminate the risk of counterfeiting. Blockchains underpin cryptocurrency tokens as a secure, decentralised digital asset.

They’re not just an asset to diversify away from inflationary fiat currency, or a hedge to protect against unwanted dictatorship. Cryptocurrencies are a (near — and increasing) substitute for fiat currency.

This means that the disorder costs of private money drop dramatically.

In fact, the counterfeiting risk for mature cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin is currently less than fiat currency. Fiat currency can still be counterfeited. A stable and secure blockchain eliminates the risk of counterfeiting entirely.

July 7, 2018

Zimbabwe and Hyperinflation: Who Wants to Be a Trillionaire?

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 3 Jan 2017How would you like to pay $417.00 per sheet of toilet paper?

Sound crazy? It’s not as crazy as you may think. Here’s a story of how this happened in Zimbabwe.

Around 2000, Robert Mugabe, the President of Zimbabwe, was in need of cash to bribe his enemies and reward his allies. He had to be clever in his approach, given that Zimbabwe’s economy was doing lousy and his people were starving. Sow what did he do? He tapped the country’s printing presses and printed more money.

Clever, right?

Not so fast. The increase in money supply didn’t equate to an increase in productivity in the Zimbabwean economy, and there was little new investment to create new goods. So, in effect, you had more money chasing the same goods. In other words, you needed more dollars to buy the same stuff as before. Prices began to rise — drastically.

As prices rose, the government printed more money to buy the same goods as before. And the cycle continued. In fact, it got so out of hand that by 2006, prices were rising by over 1,000% per year!

Zimbabweans became millionaires, but a million dollars may have only been enough to buy you one chicken during the hyperinflation crisis.

It all came crashing down in 2008 when — given that the Zimbabwean dollar basically ceased to exist — Mugabe was forced to legalize transactions in foreign currencies.

Hyperinflation isn’t unique to Zimbabwe. It has occurred in other countries such as Yugoslavia, China, and Germany throughout history. In future videos, we’ll take a closer look at inflation and what causes it.

June 29, 2018

QotD: What is a discount rate?

It is not the 20 percent savings you got by buying a new washing machine on Black Friday last year. A discount rate is a way of accounting for the fact that dollars in the future are not quite the same as dollars you have right now.

You know this, don’t you? Imagine I offered to give you a dollar right now, or a dollar a year from now. You don’t have to think hard about that decision, because you know instinctively that the dollar that’s right there, able to be instantly transferred into your sweaty little hand, is much more valuable. It can, in fact, be easily transformed into a dollar a year from now, by the simple expedient of sticking it in a drawer and waiting. It can also, however, be spent before then. It has all the good stuff offered by a dollar later, plus some option value.

Even if you’re sure you don’t want to spend it in the next year, however, a dollar later is not as good as a dollar now, because it’s riskier. That dollar I’m holding now can be taken now, and then you will definitely have it. If you’re counting on getting a dollar from me a year from now, well, maybe I’ll die, or forget, or go bankrupt.

The point is that if you’re valuing assets, and some of your assets are dollars you actually have, and others are dollars that someone has promised to give to you at some point in the future, you should value the dollars you have in your possession more highly than dollars you’re supposed to get later.

The rule for establishing an exchange rate between future dollars and current ones is known as the “discount rate.” Basically, it’s a steady annual percentage by which you lower the value of dollars you get in future years.

All you need to remember is two things: the longer you have to wait to get paid, the less that promise is worth to you today. And the higher the discount rate you apply, the lower you’re valuing that future dollar.

Megan McArdle, “Public Pensions Are Being Overly Optimistic”, Bloomberg View, 2016-09-21.

May 12, 2018

Cryptocurrency scammers

A high proportion of initial coin offerings are nothing but scammers doing what scammers do best, says Nouriel Roubini:

Initial coin offerings have become the most common way to finance cryptocurrency ventures, of which there are now nearly 1,600 and rising. In exchange for your dollars, pounds, euros, or other currency, an ICO issues digital “tokens,” or “coins,” that may or may not be used to purchase some specified good or service in the future.

Thus it is little wonder that, according to the ICO advisory firm Satis Group, 81% of ICOs are scams created by con artists, charlatans, and swindlers looking to take your money and run. It is also little wonder that only 8% of cryptocurrencies end up being traded on an exchange, meaning that 92% of them fail. It would appear that ICOs serve little purpose other than to skirt securities laws that exist to protect investors from being cheated.

If you invest in a conventional (non-crypto) business, you are afforded a variety of legal rights – to dividends if you are a shareholder, to interest if you are a lender, and to a share of the enterprise’s assets should it default or become insolvent. Such rights are enforceable because securities and their issuers must be registered with the state.

Moreover, in legitimate investment transactions, issuers are required to disclose accurate financial information, business plans, and potential risks. There are restrictions limiting the sale of certain kinds of high-risk securities to qualified investors only. And there are anti-money-laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) regulations to prevent tax evasion, concealment of ill-gotten gains, and other criminal activities such as the financing of terrorism.

In the Wild West of ICOs, most cryptocurrencies are issued in breach of these laws and regulations, under the pretense that they are not securities at all. Hence, most ICOs deny investors any legal rights whatsoever. They are generally accompanied by vaporous “white papers” instead of concrete business plans. Their issuers are often anonymous and untraceable. And they skirt all AML and KYC regulations, leaving the door open to any criminal investor.

Of course, for a significant number of people, not having the state involved in their investment is an attraction rather than a drawback. And not just criminals, but people who live in jurisdictions with uncertain reliance on the rule of law (not to mention Russia by name), where property rights are not so much “rights” as “privileges to the right sort of people”.

December 27, 2017

Will Hutton mansplains Blockchain … as he understands it

Tim Worstall tries to mitigate the damage caused by Will Hutton’s amazing misunderstanding of what blockchain technology is:

Will Hutton decides to tell us all how much Bitcoin and the blockchain is going to change our world:

Blockchain is a foundational digital technology that rivals the internet in its potential for transformation. To explain: essentially, “blocks” are segregated, vast bundles of data in permanent communication with each other so that each block knows what the content is in the rest of the chain. However, only the owner of a particular block has the digital key to access it.

So what? First, the blocks are created by “miners”, individual algorithm writers and companies throughout the world (with a dense concentration in China), who want to add a data block to the chain.

Will Hutton is, you will recall, one of those who insists that the world should be planned as Will Hutton thinks it ought to be. Something which would be greatly aided if Will Hutton had the first clue about the world and the technologies which make it up.

Blocks aren’t created by miners and individual algorithm writers, there is the one algo defined by the system and miners are confirming a block, not creating it. The blocks are not in communication with each other, they do not know what is in the rest of the chain – absolutely not in the case of earlier blocks knowing what is in later. It’s simply a permanent record of all transactions ever undertaken with an independent checking mechanism.

It’s entirely true that this could become very useful. But it’s really not what Hutton seems to think it is.