Why, though, did Germans feel such a special affinity with “die Königin“? The most obvious reason is that the Royal Family is, to a great extent, of German extraction. The connections go back more than a thousand years to the Anglo-Saxons, but in modern times they begin with George I and the House of Hanover. This reverse takeover of the British monarchy by the Germans transformed the institution in countless ways. They may be summarised in four words: music, the military, the constitution and Christmas.

Music was a language that united the English and the Germans. The key figure was, of course, Handel — the first and pre-eminent but by no means the last Anglo-German composer. Born in Halle, Georg Friedrich Händel had briefly been George I’s Kapellmeister in Hanover yet had already established himself in England before the Prince Elector of Hanover inherited the British throne in 1714.

In London — then in the process of overtaking Paris and Amsterdam to become the commercial capital of Europe — he discovered hitherto undreamt-of possibilities. There he founded three opera companies, for which he supplied more than 40 operas, and adapted a baroque Italian art form, the oratorio, to suit English Protestant tastes.

His coronation music, such as the anthem, “Zadok the Priest”, imbued the Hanoverian dynasty with a new and splendid kind of sacral majesty. But he also added to its lustre by providing the musical accompaniment for new kinds of public entertainment, such as his Music for the Royal Fireworks: 12,000 people came to the first performance.

Along with music, the Germans brought a focus on military life. Whereas for the British Isles, the Civil War and the subsequent conflicts in Scotland and Ireland had been something of an aberration, war was second nature to German princes. Among them, George II was not unusual in leading his men into battle, although he was the last British monarch to do so.

Still, the legacy of such Teutonic martial prowess was visible in the late Queen’s obsequies: uniforms and decorations, pomp and circumstance, accompanied by funeral marches composed by a German, Ludwig van Beethoven. Ironically, the German state now avoids any public spectacle that could be construed as militaristic, yet most Germans harbour boundless admiration for the way that the British monarchy enlists the ceremonial genius of the armed services.

Even more important was the German contribution to the uniquely British creation of constitutional monarchy.

Each successive dynasty has left its mark on the monarchy’s evolution: from the Anglo-Saxons and Normans (the common law) to the Plantagenets (Magna Carta and Parliament) and Tudors (the Reformation). Only the Stuarts failed this test, at least until 1688. Even after the Glorious Revolution, the Bill of Rights and other laws that conferred statutory control over the royal prerogative, the constitutional settlement still hung in the balance when Queen Anne, the last Stuart ruler, died in 1714.

Coming from a region dominated by the theory and practice of absolute monarchy, the Hanoverians had no choice but to adapt immediately and seamlessly to the realities of politics in Britain, where their role was strictly limited. Robert Walpole and the long Whig ascendancy, during which the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty embedded itself irrevocably, could not have taken place without the acquiescence and active support of the new dynasty.

George III has been accused of attempting to reverse this process. The charge is unjust. Rather, as Andrew Roberts demonstrates in his new biography, he was “a monarch who understood his extensive rights and duties under the constitution”. He still had the right to refuse royal assent to parliamentary bills, but in half a century he never once exercised his veto (the last monarch to do so was the Stuart, Queen Anne in 1708).

At a time when enlightened despotism was de rigueur on the Continent, the Hanoverians were content to participate in an unprecedented constitutional experiment in their newly acquired United Kingdom. It was neither the first Brexit, nor the last, but it happened courtesy of a Royal Family that was still very German.

Daniel Johnson, “Why Germany mourned our Queen”, The Critic, 2022-10-30.

December 29, 2023

QotD: The Hanoverian “reverse takeover of the British monarchy by the Germans”

December 18, 2023

QotD: A short history of the (long) Fifth Century

The chaotic nature of the fragmentation of the Western Roman Empire makes a short recounting of its history difficult but a sense of chronology and how this all played out is going to be necessary so I will try to just hit the highlights.

First, its important to understand that the Roman Empire of the fourth and fifth centuries was not the Roman Empire of the first and second centuries (all AD, to be clear). From 235 to 284, Rome had suffered a seemingly endless series of civil wars, waged against the backdrop of worsening security situations on the Rhine/Danube frontier and a peer conflict in the east against the Sassanid Empire. These wars clearly caused trade and economic disruptions as well as security problems and so the Roman Empire that emerges from the crisis under the rule of Diocletian (r. 284-305), while still powerful and rich by ancient standards, was not as powerful or as rich as in the first two centuries and also had substantially more difficult security problems. And the Romans subsequently are never quite able to shake the habit of regular civil wars.

One of Diocletian’s solutions to this problem was to attempt to split the job of running the empire between multiple emperors; Diocletian wanted a four emperor system (the “tetrarchy” or “rule of four”) but what stuck among his successors, particular Constantine (r. 306-337) and his family (who ruled till 363), was an east-west administrative divide, with one emperor in the east and one in the west, both in theory cooperating with each other ruling a single coherent empire. While this was supposed to be a purely administrative divide, in practice, as time went on, the two halves increasing had to make do with their own revenues, armies and administration; this proved catastrophic for the western half, which had less of all of these things (if you are wondering why the East didn’t ride to the rescue, the answer is that great power conflict with the Sassanids). In any event, with the death of Theodosius I in 395, the division of the empire became permanent; never again would one man rule both halves.

We’re going to focus here almost entirely on the western half of the empire […]

The situation on the Rhine/Danube frontier was complex. The peoples on the other side of the frontier were not strangers to Roman power; indeed they had been trading, interacting and occasionally raiding and fighting over the borders for some time. That was actually part of the Roman security problem: familiarity had begun to erode the Roman qualitative advantage which had allowed smaller professional Roman armies to consistently win fights on the frontier. The Germanic peoples on the other side had begun to adopt large political organizations (kingdoms, not tribes) and gained familiarity with Roman tactics and weapons. At the same time, population movements (particularly by the Huns) further east in Europe and on the Eurasian Steppe began creating pressure to push these “barbarians” into the empire. This was not necessarily a bad thing: the Romans, after conflict and plague in the late second and third centuries, needed troops and they needed farmers and these “barbarians” could supply both. But […] the Romans make a catastrophic mistake here: instead of reviving the Roman tradition of incorporation, they insisted on effectively permanent apartness for the new arrivals, even when they came – as most would – with initial Roman approval.

This problem blows up in 378 in an event – the Battle of Adrianople – which marks the beginning of the “decline and fall” and thus the start of our “long fifth century”. The Goths, a Germanic-language speaking people, pressured by the Huns had sought entry into Roman territory; the emperor in the East, Valens, agreed because he needed soldiers and farmers and the Goths might well be both. Local officials, however, mistreated the arriving Goth refugees leading to clashes and then a revolt; precisely because the Goths hadn’t been incorporated into the Roman military or civil system (they were settled with their own kings as “allies” – foederati – within Roman territory), when they revolted, they revolted as a united people under arms. The army sent to fight them, under Valens, engaged foolishly before reinforcements could arrive from the West and was defeated.

In the aftermath of the defeat, the Goths moved to settle in the Balkans and it would subsequently prove impossible for the Romans to move them out. Part of the reason for that was that the Romans themselves were hardly unified. I don’t want to get too deep in the weeds here except to note that usurpers and assassinations among the Roman elite are common in this period, which generally prevented any kind of unified Roman response. In particular, it leads Roman leaders (both generals and emperors) desperate for troops, often to fight civil wars against each other, to rely heavily on Gothic (and later other “barbarian”) war leaders. Those leaders, often the kings of their own peoples, were not generally looking to burn the empire down, but were looking to create a place for themselves in it and so understandably tended to militate for their own independence and recognition.

Indeed, it was in the context of these sorts of internal squabbles that Rome is first sacked, in 410 by the Visigothic leader Alaric. Alaric was not some wild-eyed barbarian freshly piled over the frontier, but a Roman commander who had joined the Roman army in 392 and probably rose to become king of the Visigoths as well in 395. Alaric had spent much of the decade before 410 alternately feuding with and working under Stilicho, a Romanized Vandal, who had been a key officer under the emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395) and a major power-player after his death because he controlled Honorius, the young emperor in the West. Honorius’ decision to arrest and execute Stilicho in 408 seems to have precipitated Alaric’s move against Rome. Alaric’s aim was not to destroy Rome, but to get control of Honorius, in particular to get supplies and recognition from him.

That pattern: Roman emperors, generals and foederati kings – all notionally members of the Roman Empire – feuding, was the pattern that would steadily disassemble the Roman Empire in the west. Successful efforts to reassert the direct control of the emperors on foederati territory naturally created resentment among the foederati leaders but also dangerous rivalries in the imperial court; thus Flavius Aetius, a Roman general, after stopping Attila and assembling a coalition of Visigoths, Franks, Saxons and Burgundians, was assassinated by his own emperor, Valentinian III in 454, who was in turn promptly assassinated by Aetius’ supporters, leading to another crippling succession dispute in which the foederati leaders emerged as crucial power-brokers. Majorian (r. 457-461) looked during his reign like he might be able to reverse this fragmentation, but his efforts at reform offended the senatorial aristocracy in Rome, who then supported the foederati leader Ricimer (half-Seubic, half-Visigoth but also quite Romanized) in killing Majorian and putting the weak Libius Severus (r. 461-465) on the throne. The final act of all of this comes in 476 when another of these “barbarian” leaders, Odoacer, deposed the latest and weakest Roman emperor, the boy Romulus Augustus (generally called Romulus Augustulus – the “little” Augustus) and what was left of the Roman Empire in the west ceased to exist in practice (Odoacer offered to submit to the authority of the Roman Emperor in the East, though one doubts his real sincerity). Augustulus seems to have taken it fairly well – he retired to an estate in Campania originally built by the late Republican Roman general Lucius Licinius Lucullus and lived out his life there in leisure.

The point I want to draw out in all of this is that it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroyed from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the “barbarian” foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed (as we’ll see next time) there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman “center” clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

December 11, 2023

QotD: The Palace of Westminster

Work outwards from this change and you will begin to have some idea of how much Britain has altered. The bits you don’t or can’t see are as unsettlingly different as those tattoos. Look up instead at the Houses of Parliament, all pinnacles, leaded windows, Gothic courtyards and cloisters, which look to the uninitiated as if they are a medieval survival. In fact they were completed in 1860, and are newer than the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The only genuinely ancient part — not used for any governing purpose — is the astonishing chilly space of Westminster Hall, faintly redolent of the horrible show trial of King Charles I, still an awkward moment in the national family album. But those who chose the faintly unhinged design wanted to make a point about the sort of country Britain then was, and they were very successful. Gothic meant monarchy, Christianity, and conservatism. Classical meant republican, pagan, and revolutionary, and mid-Victorian Britain was thoroughly wary of such things, so Gothic was chosen and the Roman Catholic genius Augustus Welby Pugin let loose upon the design. Wherever you are in the building, it is hard to escape the feeling of being either in a church, or in a country house just next to a church. The very chimes of the bell tower were based upon part of Handel’s great air from The Messiah: “I know that my Redeemer liveth”.

I worked for some years in this odd place. It is by law a Royal Palace, so nobody was ever officially allowed to die on the premises, in case the death had to be inquired into by some fearsome, forgotten tribunal, perhaps a branch of Star Chamber. Those who appeared to have deceased were deemed to be still alive and hurried to a nearby hospital where life could be pronounced extinct and an ordinary inquest held. We were also exempt from the alcohol laws that used in those days to keep most bars shut for a lot of the time, and if the drinks were not free they were certainly amazingly cheap.

In my years of wandering its corridors and lobbies, of hanging about for late-night votes and dozing in committee rooms, I came to loathe British politics and to mistrust the special regiment of journalists (far too close to their sources) who write about it. I had hoped for a kingdom of the mind and found a squalid pantry in which greasy, unprincipled deals were made by people who were no better than they ought to be.

But I came to love the building. Once you had got past the police sentinels, who knew who everyone was, you could go everywhere, even the thrilling ministerial corridor behind the Speaker’s chair, from which Prime Ministers emerged to face what was then the genuine ordeal of Parliamentary questions, twice a week. There was a rifle range beneath the House of Lords, set up during World War I to make sure honorable members of both Houses would be able to shoot Germans accurately if they ever met any. There was a room where they did nothing but prepare vast quantities of cut flowers, and which perfumed the flagstone corridor in which it lay. There was a convivial staff bar (known to few) where the beer was the best in the building and politicians in trouble would hide from their colleagues. The Lords had a whole half of the Palace, with lovely murals illustrating noble moments of our history, and the Chief Whip’s cosy, panelled office where reporters would be summoned once a week for dangerous gossip and perilously large glasses of whisky or very dry sherry, generously refilled. And high up in the roof, looking down over the murky Thames, was the room where the government briefed us, in meetings whose existence we were sworn never to reveal. Now they are pretty much public, so the real briefings must happen somewhere else, I suppose.

Peter Hitchens, “An Empty Parliament”, First Things, 2017-10-03.

November 29, 2023

Alfred the Great

Ed West‘s new book is about the only English king to be known as “the Great”:

There are no portraits of King Alfred from his time period, so representations like this 1905 stained glass window in Bristol Cathedral are all we have to visually represent him.

Photo by Charles Eamer Kempe via Wikimedia Commons.

History was once the story of heroes, and there is no greater figure in England’s history than the man who saved, and helped create, the nation itself. As I’ve written before, Alfred the Great is more than just a historical figure to me. I have an almost Victorian reverence for his memory.

Alfred is the subject of my short book Saxons versus Vikings, which was published in the US in 2017 as the first part of a young adult history of medieval England. The UK edition is published today, available on Amazon or through the publishers. (use the code SV20 on the publisher’s site, valid until 30 November, which gives 20% off). It’s very much a beginner’s introduction, aimed at conveying the message that history is just one long black comedy.

The book charts the story of Alfred and his equally impressive grandson Athelstan, who went on to unify England in 927. In the centuries that followed Athelstan may have been considered the greater king, something we can sort of guess at by the fact that Ethelred the Unready named his first son Athelstan, and only his eighth Alfred, and royal naming patterns tend to reflect the prestige of previous monarchs.

Yet while Athelstan’s star faded in the medieval period, Alfred’s rose, and so by the fifteenth century the feeble-minded Henry VI was trying to have him made a saint. This didn’t happen, but Alfred is today the only English king to be styled “the Great”, and it was a word attached to him from quite an early stage. Even in the twelfth century the gossipy chronicler Matthew Paris is using the epithet, and says it’s in common use.

However, much of what is recorded of him only became known in Tudor times, partly by accident. Henry VIII’s break from Rome was to have a huge influence on our understanding of history, chiefly because so many of England’s records were stored in monasteries.

Before the development of universities, these had been the main intellectual centres in Christendom, indeed from where universities would grow. Now, along with relics, huge amounts of them would be lost, destroyed, sold … or preserved.

It was lucky that Matthew Parker, the sixteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury with a keen interest in history, had a particularly keen interest in Alfred. It was Parker who published Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574, having found the manuscript after the dissolution of the monasteries, a book that found itself in the Ashburnham collection amassed by Sir Robert Cotton in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Sadly, the original Life was burned in a famous fire at Ashburnham House in Westminster on October 23, 1731. Boys from nearby Westminster School had gone into the blaze alongside the owner and his son to rescue manuscripts, but much was lost, among them the only surviving manuscript of the Life of Alfred, as well as that of Beowulf. In fact the majority of recorded Anglo-Saxon history had gone up in smoke in minutes.

A copy of Beowulf had also been made, although the poem only became widely known in the nineteenth century after being translated into modern English. The fire also destroyed the oldest copy of the Burghal Hidage, a unique document listing towns of Saxon England and provisions for defence made during the reign of Alfred’s son Edward the Elder. An eighth-century illuminated gospel book from Northumbria was also lost.

So it is lucky that Parker had had The Life of Alfred printed, even if he had made alterations in his copy that to historians are infuriating because they cannot be sure if they are authentic. He probably added the story about the cakes, for instance, although this had come from a different Anglo-Saxon source.

We also know that Archbishop Parker was a bit confused, or possibly just lying; he claimed Alfred had founded his old university, Oxford, which was clearly untrue, and he was probably trying to make his alma mater sound grander than Cambridge. Oxford graduates down the years have been known to do this on one or two occasions.

November 22, 2023

“[T]he Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists”

I quite like a lot of what Ed West covers at Wrong Side of History, but I’m not convinced by his summary of the character of King Richard III nor do I believe him guilty of murdering his nephews, the famed “Princes in the Tower”:

As Robert Tombs put it in The English and their History, no other country but England turned its national history into a popular drama before the age of cinema. This was largely thanks to William Shakespeare’s series of plays, eight histories charting the country’s dynastic conflict from 1399 to 1485, starting with the overthrow of the paranoid Richard II and climaxing with the War of the Roses.

This second part of the Henriad covered a 30-year period with an absurdly high body count – three kings died violently, seven royal princes were killed in battle, and five more executed or murdered; 31 peers or their heirs also fell in the field, and 20 others were put to death.

And in this epic national story, the role of the greatest villain is reserved for the last of the Plantagenets, Richard III, the hunchbacked child-killer whose defeat at Bosworth in 1485 ended the conflict (sort of).

Yet despite this, no monarch in English history retains such a fan base, a devoted band of followers who continue to proclaim his innocence, despite all the evidence to the contrary — the Ricardians.

One of the most furious responses I ever provoked as a writer was a piece I wrote for the Catholic Herald calling Richard III fans “medieval 9/11 truthers”. This led to a couple of blogposts and several emails, and even an angry phone call from a historian who said I had maligned the monarch.

This was in the lead up to Richard III’s reburial in Leicester Cathedral, two and a half years after the former king’s skeleton was found in a car park in the city, in part thanks to the work of historian Philippa Langley. It was a huge event for Ricardians, many of whom managed to get seats in the service, broadcast on Channel 4.

Apparently Philippa Langly’s latest project — which is what I assume raised Ed’s ire again — is a new book and Channel 4 documentary in which she makes the case for the Princes’ survival after Richard’s reign although (not having read the book) I’d be wary of accepting that they each attempted to re-take the throne in the guises of Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.

The Ricardian movement dates back to Sir George Buck’s revisionist The History of King Richard the Third, written in the early 17th century. Buck had been an envoy for Elizabeth I but did not publish his work in his lifetime, the book only seeing the light of day a few decades later.

Certainly, Richard had his fans. Jane Austen wrote in her The History of England that “The Character of this Prince has been in general very severely treated by Historians, but as he was a York, I am rather inclined to suppose him a very respectable Man”.

But the movement really began in the early 20th century with the Fellowship of the White Boar, named after the king’s emblem, now the Richard III Society.

It received a huge boost with Josephine Tey’s bestselling 1951 novel The Daughter of Time in which a modern detective manages to prove Richard innocence. Paul Murray Kendall’s Richard the Third, published four years later, was probably the most influential non-fiction account to take a sympathetic view, although there are numerous others.

One reason for Richard’s bizarre popularity is that the Tudors were indeed pretty awful, and that the writers who lived under this dynasty did serve as propagandists.

Writers tend to serve the interests of the ruling class. In the years following Richard III’s death John Rous said of the previous king that “Richard spent two whole years in his mother’s womb and came out with a full set of teeth and hair streaming to his shoulders”. Rous called him “monster and tyrant, born under a hostile star and perishing like Antichrist”.

However, when Richard was alive the same John Rous was writing glowing stuff about him, reporting that “at Woodstock … Richard graciously eased the sore hearts of the inhabitants” by giving back common lands that had been taken by his brother and the king, when offered money, said he would rather have their hearts.

Certainly, there was propaganda. As well as the death of Clarence, William Shakespeare — under the patronage of Henry Tudor’s granddaughter — also implicated Richard in the killing the Duke of Somerset at St. Albans, when he was a two-year-old. The playwright has him telling his father: “Heart, be wrathful still: Priests pray for enemies, but princes kill”. So it’s understandable why historians might not believe everything the Bard wrote about him.

I must admit to a bias here, as I wrote back in 2011:

In the interests of full disclosure, I should point out that I portrayed the Earl of Northumberland in the 1983 re-enactment of the coronation of Richard III (at the Cathedral Church of St. James in Toronto) on local TV, and I portrayed the Earl of Lincoln in the (non-televised) version on the actual anniversary date. You could say I’m biased in favour of the revisionist view of the character of good King Richard.

November 6, 2023

QotD: The “German Catastrophe”

The obvious frame for this book is what has been fittingly termed the German Catastrophe: the fate of Germany in the late 19th and early 20th century, as viewed from the perspective of German nationalists who were not Nazis — the perspective of people like Ernst Jünger.

Germany had entered modernity without democracy. The Kaiserreich (German Empire) had united the many small German states, aggressively worked to catch up with industrialization, built a state to rival France and Great Britain, and remained authoritarian throughout. Commoners had negligible political influence. They did get social insurance, but not through their own political power but granted top-down, as an appeasement to undermine socialist movements. Civil marriage, secularized state education, prospering state universities and a long series of modernizing laws kept increasing state power. And that meant executive power. There were parties, a parliament and a newly homogenized judiciary, but they had little power to check the executive.

And this entire development was accompanied by a lot of theorizing about this new German nation. Much of this theorizing ended up justifying authoritarianism, by making quickly-spreading myths about how obedience to authority, respect for aristocracy and love for tradition were uniquely German traits that set Germans apart from the French and the Jews and other dubious foreigners. Such myths, and opposition to them, colored the German population’s hard work to get accustomed to industrialization, urbanization, education, rapid population growth, militarization, national media and various culture wars.

This had seemed to work okay-ish while Bismarck, wielding both enormous ruthlessness and enormous political acumen, had navigated Germany through the trials and tribulations of the late 19th century, largely at the expense of France. But in 1890, Emperor Wilhelm II had taken over authority with less ruthlessness and much less political acumen. While his populace remained nearly unable to influence politics, Wilhelm II made critical political mistakes, especially in dealing with other European powers.

These mistakes culminated in the first World War. You know how that one went.

Germany’s defeat led into Germany’s first real democracy. Everyone was very obviously new to this. The right attacked the new state, falsely claiming it had needlessly capitulated. The left also attacked the new state, because it wasn’t Soviet-Union-like enough. There was a lot of political violence. The massive damage incurred in the war, and the restrictions and reparations Germany had accepted in the peace settlement, put massive strains on an already fragile political system. Elections were tumultuous and frequent. Hyperinflation caused a huge crisis in 1923, and the Great Depression of 1929 was another huge disaster for Germany. Overall, the abolition of authoritarianism was widely felt to be a mistake.

This seeming mistake was fixed when Hitler stepped in. And you know how that one went.

Anonymous, “Your Book Review: On the Marble Cliffs”, Astral Codex Ten, 2023-07-28.

November 5, 2023

Guy Fawkes and The Gunpowder Plot 1605

The History Chap

Published 4 Nov 2022The story behind Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, the audacious plan to kill the king of England. It is also the complicated story behind our annual Bonfire Night celebrations.

In 1605 a group of dissident Catholics came within a whisker of one of the greatest assassination coups in history — blowing up the King of England, and his government as he attended parliament in London. 36 barrels of gunpowder (approximately 1 tonne of explosives) had been placed directly under where he would open parliament. Experts estimate that no one within 300 feet would have survived.

Had it succeeded it would have rivalled 9/11 in its audacity and would have changed English (& arguably world) history forever. But who were the plotters, what were they trying to achieve and how close did they really come to success? Were they freedom fighters or 17th century terrorists? And why is only one conspirator, Guy Fawkes, remembered when he wasn’t even the brains behind the operation?

After years of persecution by England’s Protestants, a small group of Catholic nobles under Robert Catesby (aka Robin Catesby) decided to take matters into their own hands and blow up the king (King James I of England / James VI of Scotland) whilst he attended parliament in London.

Guy Fawkes (aka Guido Fawkes) smuggled 36 barrels of gunpowder into a cellar directly beneath the hall where parliament would meet in the Palace of Westminster. In the early hours of 5th November 1605, he was arrested by guards who had been tipped off about the gunpowder plot. After three days of torture in the Tower of London, Guy Fawkes finally broke and named his fellow conspirators.

The conspirators, under Robert Catesby, had fled London for the English midlands where they hoped to abduct the king’s daughter and organise a catholic rising. Both failed to materialise and Catesby’s small band were surrounded by a government militia at Holbeach House, just outside Kingswinford in Staffordshire. A brief shoot-out resulted in the death of some of the Catholic rebels (including their leader, Catesby) and the arrest of the others.

The surviving gunpowder plotters (including Guy Fawkes) were executed in London at the end of January 1606, by the grisly execution reserved for traitors — Hanged, drawn and quartered (quite literally a “living death”).

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a complete failure but the event is still celebrated on the 5th November every year on Bonfire Night.

(more…)

October 28, 2023

QotD: Deposing King Charles I

It’s 1642, and once again the English are contemplating deposing a king for incompetence. Alas, the Reformation forces the rebels to confront the issue the deposers of Edward II and Richard II could duck: Divine sanction. The Lords Appellant could very strongly imply that Richard II had lost “the mandate of heaven” (to import an exoteric term for clarity), but they didn’t have to say it – indeed, culturally they couldn’t say it. The Parliamentarians had the opposite problem – not only could they say it, they had to, since the linchpin of Charles I’s incompetence was, in their eyes, his cack-handed efforts to “reform” religious practice in his kingdoms.

But on the other hand, if they win the ensuing civil war, that must mean that God’s anointed is … Oliver Cromwell, which is a notion none of them, least of all Oliver Cromwell, was prepared to accept. Moreover, that would make the civil war an explicitly religious war, and as the endemic violence of the last century had so clearly shown, there’s simply no way to win a religious war (recall that the ructions leading up to the English Civil War overlapped with the last, nastiest phase of the Thirty Years’ War, and that everyone had a gripe against Charles for getting involved, or not, in the fight for the One True Faith on the Continent).

The solution the English rebels came up with, you’ll recall, was to execute Charles I for treason. Against the country he was king of.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

October 19, 2023

QotD: Revolutionary terrorism in Tsarist Russia

The Russian Revolution should not have been a surprise. For decades leading up to it, Russia was gripped by an ever-rising wave of sadistic revolutionary terrorism. Gary Saul Morson describes it like this:

Country estates were burnt down and businesses were extorted or blown up. Bombs were tossed at random into railroad carriages, restaurants, and theaters. Far from regretting the death and maiming of innocent bystanders, terrorists boasted of killing as many as possible, either because the victims were likely bourgeois or because any murder helped bring down the old order. A group of anarchocommunists threw bombs laced with nails into a café bustling with two hundred customers in order “to see how the foul bourgeois will squirm in death agony”.

Instead of the pendulum’s swinging back — a metaphor of inevitability that excuses people from taking a stand — the killing grew and grew, both in numbers and in cruelty. Sadism replaced simple killing. As Geifman explains, “The need to inflict pain was transformed from an abnormal irrational compulsion experienced only by unbalanced personalities into a formally verbalized obligation for all committed revolutionaries”. One group threw “traitors” into vats of boiling water. Others were still more inventive. Women torturers were especially admired.

What do you think was the response of “moderate” Russians to all of this? Academics and journalists and liberal politicians and forward-thinking businessmen, that sort of people. If your guess is that it horrified them and caused them to grudgingly support the forces of order, you would be … wrong. In fact, quite the opposite: making excuses for terrorism became trendy. Lawyers and teachers and doctors and engineers held fundraisers for terrorists, donated to charities that supported insurrectionary behavior, and turned their offices into safe houses. Apparently chaos and death were one thing, but it was much, much scarier for your friends and neighbors to think you might be a reactionary. Naturally this same class of people were the first to be herded into the camps, or into the cork-lined cellars in the basement of the Lubyanka. Despite all my boundless cynicism about human nature, I still can’t quite believe that this all actually happened.

Dostoevsky predicted it 50 years beforehand.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Demons, by Fyodor Dostoevsky”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-07-17.

October 16, 2023

QotD: Differentials of “information velocity” in a feudal society

[News of the wider world travels very slowly from the Royal court to the outskirts, but] information velocity within the sticks […] is very high. Nobody cares much who this “Richard II” cat was, or knows anything about ol’ Whatzisface – Henry Something-or-other – who might’ve replaced him, but everyone knows when the local knight of the shire dies, and everything about his successor, because that matters. So, too, is information velocity high at court – the lords who backed Henry Bolingbroke over Richard II did so because Richard’s incompetence had their asses in a sling. They were the ones who had to depose a king for incompetence, without admitting, even for a second, that

a) competence is a criterion of legitimacy, and

b) someone other than the king is qualified to judge a king’s competence.Because admitting either, of course, opens the door to deposing the new guy on the same grounds, so unless you want civil war every time a king annoys one of his powerful magnates, you’d best find a way to square that circle …

… which they did, but not completely successfully, because within two generations they were back to deposing kings for incompetence. Turns out that’s a hard habit to break, especially when said kings are as incompetent as Henry VI always was, and Edward IV became. Only the fact that the eventual winner of the Wars of the Roses, Henry VII, was as competent as he was as ruthless kept the whole cycle from repeating.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

October 14, 2023

A Jacobite spy for Bonnie Prince Charlie

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes talks about the career of John Holker of Manchester, cloth manufacturer, who joined the army of Prince Charles Edward Stewart in 1745, and eventually became an expert in industrial espionage:

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, 1720 – 1788. Eldest Son of Prince James Francis Edward Stuart.

Portrait by Allan Ramsay, National Galleries Scotland via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve lately been reading about one of history’s greatest spies — not a James Bond-like agent with licence to kill, but a master of industrial espionage, John Holker.1

Holker was originally from Manchester, in Lancashire, where he was a skilled cloth manufacturer in the early eighteenth century, his specialty being calendering — a finishing process to give cloth a kind of sheen or glazed effect. But Holker was also a Catholic and a Jacobite — a believer in the claim of the Catholic descendants of the deposed king James II to be the rightful rulers of Great Britain, instead of the Hanoverian George I and George II who had only succeeded to the throne because they were Protestants. In 1745 James II’s grandson Charles, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie — likely the “Bonnie” who lies over the ocean in the famous song — landed in the Scottish Highlands and raised the royal standard. Charles’s uprising defeated the British troops stationed in Scotland, captured Edinburgh, and then marched down the west coast of England, capturing Carlisle and entering Lancashire.

To Holker, who had been born in the same year as the last Jacobite rebellion in 1719, the arrival of Charles in Manchester must have seemed like a once-in-a-generation opportunity. He and his business partner instantly joined Charles’s troops and he was appointed a lieutenant. But Manchester was the last place to provide many eager volunteers for the uprising, and when Charles reached Derby he lost heart and turned around. Holker and his business partner ended up being left to garrison Carlisle as Charles and his force retreated into Scotland to hunker down, and they were soon captured by the British troops sent to quash the uprising. They were then, as officers, sent to Newgate prison in London to sit with their legs bound in irons and await trial and certain execution.

But they never made it to trial. In the first demonstration of Holker’s extraordinary talent for espionage, they escaped. Holker had been allowed visitors in prison, so had drawn on London’s crypto-Jacobite circle to smuggle in files, ropes, and information about the prison and its surroundings. They managed to file through the leg-irons and window bars, climbed up the gutters onto the prison roof, and then used planks from the cell’s tabletop to cross onto the roof of a nearby house. In the event, they disturbed a dog guarding the house, and so Holker hid in a water-butt and became separated from the others. He eventually found refuge at a crypto-Jacobite’s house, then escaped into the countryside before managing to make his way to France.

In France, Holker joined his fellow veterans of the failed uprising of ‘45, becoming a lieutenant in a Jacobite regiment of the French army. He fought for the French in the Austrian Netherlands — present-day Belgium — against the Hapsburgs, the Hanoverians, the Dutch, and the British. Even more extraordinary, however, was that when Bonnie Prince Charlie wanted to go in secret to England in 1750, it was Holker who went with him as his sole companion and guide. Although Charles failed to persuade his supporters in England to rise up in rebellion on their own, Holker managed to get the prince secretly and safely to London and back.

By the time Holker reached his early thirties he had been an industrialist, rebel, prisoner, fugitive, soldier, undercover agent, and even spy-catcher: he successfully identified a spy for the British in Charles’s circle, even if Charles failed to heed his warning. But in 1751 Holker’s career took yet another turn when he was recruited by the French government as an industrial spymaster.

Holker’s chief task was to steal British textile technologies.

1. Unless otherwise stated, I’ve drawn much of my information on Holker and the industries that the French attempted to copy from John R. Harris, Industrial Espionage and Technology Transfer: Britain and France in the 18th Century (Taylor & Francis, 2017), particularly chapter 3.

October 7, 2023

QotD: Saudi princes

I see that Prince Abdul-Rahman bin Abdulaziz al Saud died the other day. If you’re having trouble keeping track of your Saudi princes, well, I don’t blame you. Unlike the closely held princely titles of the House of Windsor, the House of Saud is somewhat promiscuous with the designation: there are (at the time of writing) over 10,000 Saudi “princes” running around the country — and, in fact, at this time of year, more likely running around Mayfair and the French Riviera, exhausting the poor old blondes from the escort agencies. I believe that’s Abdul-Rahman at right, although to be honest all Saudi princes look alike to me, except that some wear white and others look very fetching in gingham. As I once remarked to Sheikh Ghazi al-Ghosaibi, the late cabinet minister, he was the only Saudi I knew who wasn’t a prince.

Abdul-Rahman was a longtime Deputy Defense Minister, whose catering company, by happy coincidence, held the catering contract for the Defense Ministry. The first Saudi prince to be educated in the west, he was a bit of a cranky curmudgeon in later years, mainly because of changes to the Saudi succession that eliminated any possibility of him taking the throne. But he nevertheless held a privileged place as the son of Ibn Saud, the man who founded the “nation” and stapled his name to it. When I say “the son”, I mean a son: Ibn Saud had approximately 100 kids, the first born in 1900, the last over half-a-century later, in 1952, a few months before ol’ Poppa Saud traded in siring for expiring.

Abdul-Rahman’s mother was said to be Ibn Saud’s favorite among his 22 wives — or, at any rate, one of the favorites. Top Five certainly. She also had the highest status, because she bore him more boys — seven — than any other other missus. They’re known as the Sudairi Seven or, alternatively, the Magnificent Seven. She also gave him seven daughters. They’re known as the seven blackout curtains standing over in the corner. This splendidly fertile lady’s name was Hussa bint Ahmed, and she was Ibn Saud’s cousin once removed and then, if I’m counting correctly, his eighth wife. But she’s a bit like the Grover Cleveland of the House of Saud — in that he’s counted as the 22nd and 24th President of the United States, and she’s the eighth wife and also either the tenth or eleventh. He first married her when he was 38 and she was 13. But he divorced her and then remarried her. In between their marriages she was married to his brother, but Ibn Saud was a sentimental lad and never got over his child-bride-turned-sister-in-law, so he ordered his brother to divorce her.

Don’t worry, though: In the House of Saud, it’s happy endings all round. Two of their daughters wound up marrying two of the sons of another brother of Ibn Saud. The Saudi version of Genealogy.com must be a hoot: “Hey, thanks for the DNA sample. You’re 53.8 per cent first cousin, and 46.2 per cent uncle.”

Mark Steyn, “The Son of the Man who Put the Saud in Saudi Arabia: Prince Abdul-Rahman bin Abdulaziz al Saud, 1931-2017”, Steyn Online, 2017-07-18.

September 26, 2023

QotD: Bad kings, mad kings, and bad, mad kings

An incompetent king doesn’t invalidate the very notion of monarchy, as monarchs are men and men are fallible. A bad, mad king (or a minor child) would surely find himself sidelined, or suffering an unfortunate hunting accident, or in extreme cases deposed, but the process of replacing X with Y on the throne didn’t invalidate monarchy per se. Deposing a king for incompetence was a very dangerous maneuver for lots of reasons, but it could be, and was, recast as a kind of “mandate of heaven” thing. Though they of course didn’t say that, the notion wasn’t a particularly tough sell in the age of Avignon and Antipopes.

But notice the implied question here: Sold to whom?

That’s where the idea of “information velocity” comes in. Exaggerating only a little for effect: Most subjects of most monarchs in the Medieval period had only the vaguest idea of who the king even was. Yeah, sure, theoretically you know that your lord’s lord’s lord owes homage to some guy called “Edward II” – that whole “feudal pyramid” thing – but as to who he might be, who cares? You’ll never lay eyes on the guy, except maybe as a face on a coin … and when will you ever even see one of those? So when you finally hear, weeks or months or years after the fact, that “Richard II” has been deposed, well … vive le roi, I guess. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss, and meanwhile life goes on the same as it ever did.

Information velocity out to the sticks, in other words, was very low. By the time you find out what the great and the good are up to, it’s already over. And, of course, the reverse – so long as the taxes come in on time, on the rare occasions they’re levied (imagine that!), the king doesn’t much care what his vassal’s vassals’ vassals’ vassals are up to.

Severian, “Inertia and Incompetence”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-25.

September 11, 2023

How the Russian Army Collapsed

The Great War

Published 9 Sept 2023As 1917 began, the Russian army was larger and better-equipped than ever before. Within weeks, the Tsar and his dynasty were gone, and by the summer, the Russian army was disintegrating before the eyes of its generals — but how exactly did one of the most powerful armies in the world collapse?

(more…)

September 3, 2023

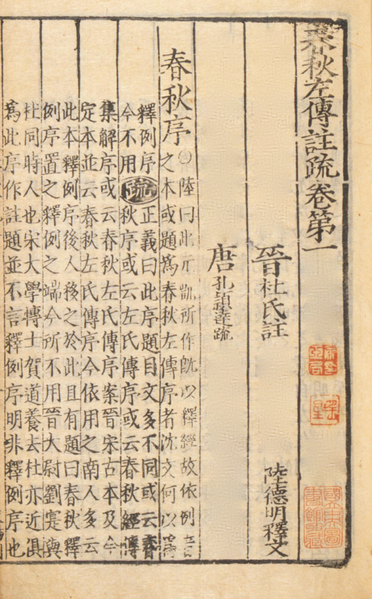

“This is the world of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and the Zuozhuan“

Another anonymous book review at Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten considers the Zuozhuan, a commentary and elaboration of the more bare-bones historical record of the Spring and Autumn Annals:

To tell the story of the fall of a realm, it’s best to start with its rise.

More than three thousand years ago, the Shang dynasty ruled the Chinese heartland. They raised a sprawling capital out of the yellow plains, and cast magnificent ritual vessels from bronze. One of the criteria of civilization is writing, and they had the first Chinese writing, incising questions on turtle shells and ox scapulae, applying a heated rod, and reading the response of the spirits in the pattern of cracks. “This year will Shang receive good harvest?” “Is the sick stomach due to ancestral harm?” “Offer three hundred Qiang prisoners to [the deceased] Father Ding?” The kings of Shang maintained a hegemony over their neighbors through military prowess, and sacrificed war captives from their campaigns totaling in the tens of thousands for the favor of their ancestors.

But the Shang faced growing threat from the Zhou, a once-subordinate people from west beyond the mountains. Inspired by a rare conjunction of the planets in 1059 BC, the Zhou declared that there was such a thing as the Mandate of Heaven, a divine right to rule—and while the Shang had once held it, their misrule and immorality had forced the Mandate to pass to the Zhou. Thirteen years later, the Zhou and their allies defeated the Shang in battle, seized their capital, drove their king to suicide, and supplanted them as overlords of the Central Plains.

If the Shang were goth jocks, the Zhou were prep nerds. In grave goods, food-serving vessels replaced wine vessels. Mass human sacrifice disappeared, while bureaucracy expanded. The Shang lacked the state power to administer their surrounding subject peoples so much as intimidate them into line; the Zhou, galvanized by a rebellion not long after the conquest, put serious thought into consolidating their control. While the king remained in the west to rule over the original Zhou lands, he sent relatives and allies east into the conquered territories to establish colonies at strategically important locations, anchoring Zhou rule in a sprawling network of hereditary regional lords bound together by blood, marriage, custom, and ancestor worship of the Heaven-blessed founding Zhou kings.

For generations, the system worked, ensuring military successes at the borders and stability in the interior. The first reigns of the dynasty became a golden age in the cultural imagination for thousands of years. But by the dynasty’s second century, barbarian incursions were putting the state on the defensive, and surviving records hint at waning control over the regional lords and power struggles at court. 771 BC marked a breaking point, when barbarians allied with disgruntled nobles to overrun the royal domain and kill King You of Zhou.

Legend has it that the king was bewitched by his new consort, a melancholy beauty born from a virgin impregnated by the touch of a black salamander. Desperate to make her laugh, the king pranked his lords by lighting the beacon fires intended to summon them in case of invasion. When she delighted at the sight, he kept playing the same trick until the lords got sick of him and stopped coming, which doomed him when the barbarians actually invaded.

But the historical reality seems to be the usual sordid political struggle around a new consort — and heir — threatening the power of the old one. The original queen’s powerful father allied with barbarians to root out the upstart, only to get maybe more than he bargained for. Sure, he put his grandkid on the throne in the end, but the royal house had been devastated. It would never regain the ancestral lands it had lost to the barbarians, the direct holdings that filled its treasury and provided for its armies. The king retreated east into the Central Plains, playing ground of lords that were now more powerful than him. While the royal line remained symbolically important, as holder of the Mandate of Heaven from which all the states derived their legitimacy, the loss of central authority in every other sense would unleash centuries of intensifying interstate warfare and upheaval.

This is the world of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and the Zuozhuan.

The Spring

“Spring and Autumn Annals” is a bit of a redundant translation, since “spring and autumn” was just an old way of saying “year”, and thus, “annals”. And technically, there were multiple Spring and Autumn Annals — every state kept, in addition to court and administrative documents, its own laconic record of each year’s wars, diplomacy, natural phenomena, major rites, and notable deaths. But the state of Lu’s is special, because Confucius was from Lu. He’s said to have personally edited and compiled the extant version of its 242-year-long Spring and Autumn, loading each character with weighty yet subtle moral deliberation. This ensured it a place in the Confucian canon, and its survival where every other state’s annals have been lost to time. The era that it covers is named the Spring and Autumn period after the text, not the other way around.

Taken on its own, though, the Annals is little more than a list of dry facts. For example, the first year reads:

The first year, spring, the royal first month.

In the third month, our lord and Zhu Yifu swore a covenant at Mie.

In summer, in the fifth month, the Liege of Zheng overcame Duan at Yan.

In autumn, in the seventh month, the Heaven-appointed king sent his steward Xuan to us to present the funeral equipment for Lord Hui and Zhong Zi.

In the ninth month, we swore a covenant with a Song leader at Su.

In winter, in the twelfth month, the Zhai Liege came.

Gongzi Yishi died.

Who is Zhu Yifu? Who’s Duan? What’s all this about “overcoming”? Where does the moral deliberation come in? This canon badly needs meta, and the most notable of the ancient commentaries written for the Spring and Autumn Annals is the Zuozhuan. Ten times as long as the text it’s for, the Zuozhuan is the flesh on the Annals‘ bare bones, one of the foundational works of ancient Chinese literature and history-writing in its own right.

While tradition attributes the text’s authorship to Zuo Qiuming, a contemporary of Confucius, most modern historians date its compilation to the century after. In its extant form, it’s presented interleaved with the Annals, so that after the Annals’ account of each year, with entries such as …

In summer, in the sixth month, on the yiyou day (26), Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi.

… you have the Zuozhuan’s account of the year, mostly composed of elaborations upon the above entries, such as:

The leaders of Chu presented a large turtle to Lord Ling of Zheng. Gongzi Song and Gongzi Guisheng were about to have an audience with the lord. Gongzi Song’s index finger moved involuntarily. He showed it to Gongzi Guisheng and said, “On other days when my finger did this, I always without fail got to taste something extraordinary.” As they entered, the cook was about to take the turtle apart. They looked at each other and smiled. The lord asked why, and Gongzi Guisheng told him. When the lord had the high officers partake of the turtle, he called Gongzi Song forward but did not give him any. Furious, Gongzi Song dipped his finger into the cauldron, tasted the turtle, and left. The lord was so enraged that he wanted to kill Gongzi Song. Gongzi Song plotted with Gongzi Guisheng to act first. Gongzi Guisheng said, “Even with an aging domestic animal, one is reluctant to kill it. How much more so then with the ruler?” Gongzi Song turned things around and slandered Gongzi Guisheng. Gongzi Guisheng became fearful and complied with him. In the summer, they assassinated Lord Ling.

The text says, “Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi”: this is because he fell short in weighing the odds. The noble man said, “To be benevolent without martial valor is to achieve nothing.” In all cases when a ruler is assassinated, naming the ruler [with his personal name rather than his title] means that he violated the way of rulership; naming the subject means that the blame lies with him.

There’s a few too many mythological creatures and just-so stories for the Zuozhuan to be taken entirely at face value, but it’s clear that its creator(s) had access to diverse now-lost records for the era portrayed. For example, some of the events show a two-month dating discrepancy — one of the states used a different calendar, and most likely the creator(s) overlooked the difference when borrowing from sources from that state. While the overall level of historical rigor versus 4th century BC authorial invention remains under heated debate, the Zuozhuan is undeniably the most comprehensive written source on its era that we have.

And importantly, it’s enjoyable.

You can think of the Zuozhuan as the Gene Wolfe of ancient historical works. It’s not an easy read, especially in translation, where names that are visibly distinct in the original (e.g. 季, 急, 姬, etc.) all get unhelpfully collapsed into one transliteration (Ji). The work drops you into a whirl of nouns and events, some of them one-off asides, others part of long-running narrative threads that might only surface again decades of entries later. While a casual readthrough still offers plenty of rewards, putting together all the subtext, references, and connections between entries is an endeavor that’s occupied readers for millennia. Your unreliable narrator remains enigmatic on most of the events he presents, leaving interpretation as an exercise for the reader; when he does speak, either directly or in the voice of the “noble man”, he can raise more questions than he answers. For one, the rule about the naming of an assassinated ruler largely holds in the Annals, but seems to have some notable exceptions.

But if you’re willing to plunge in, the work offers an experience unlike anything else.