Algal the Bard

Published 14 Aug 2022Song composed by Kate Bush.

(more…)

December 13, 2022

December 10, 2022

The “Dark” Ages were fine, actually — History Hijinks

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 5 Aug 2022Curb your Crusading – the artwork, literature, and scholarship are far more interesting.

SOURCES & Further Reading: China: A History by John Keay, Byzantium & Sicily & Venice by John Julius Norwich, Great Courses Lecture series Foundations of Western Civilization by Thomas F. X. Noble lectures 27 through 38: “The Emergence of the Catholic Church”, “Christian Culture in Late Antiquity”, “Muhammad and Islam”, “The Birth of Byzantium”, “Barbarian Kingdoms in the West”, “The World of Charlemagne”, “The Carolingian Renaissance”, “The Expansion of Europe”, “The Chivalrous Society”, “Medieval Political Traditions I”, “Medieval Political Traditions II”, and “Scholastic Culture”.

(more…)

QotD: The Western Roman Empire – “decline and fall” or “change and continuity”?

So who are our [academic] combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the “history of the history” – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields “connect” in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

With that out of the way, the old view, that of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) and indeed largely the view of the sources themselves, was that the disintegration of the western half of the Roman polity was an unmitigated catastrophe, a view that held largely unchallenged into the last century; Gibbon’s great work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1789) gives this school its name, “decline and fall“. While I am going at points to gesture to Gibbon’s thinking, we’re not going to debate him; he is the “old man” of our title. Gibbon himself largely exists only in historiographical footnotes and intellectual histories; he is not at this point seriously defended nor seriously attacked but discussed as the venerable, but now out of date, origin point for all of this bickering.

The real break with that view came with the work of Peter Brown, initially in his The World of Late Antiquity (1971) and more or less canonically in The Rise of Western Christendom (1st ed. 1996; 2nd ed. 2003, 3rd ed. 2013). The normal way to refer to the Peter Brown school of thought is “change and continuity” (in contrast to the traditional “decline and fall”), though I rather like James O’Donnell’s description of it as the Reformation in late antique studies.

Among medievalists this reformed view, which focuses on continuity of culture and institutions from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, remains essentially the orthodoxy, to the point that, for instance, the very recent (and quite excellent) The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (2021) can present this vision as an uncomplicated fact, describing the “so-called Fall of Rome” and noting that “there was never a moment in the next thousand years in which at least one European or Mediterranean ruler didn’t claim political legitimacy through a credible connection to the empire of the Romans” and that “the idea that Rome ‘fell’ on the other hand, relies upon a conception of homogeneity – of historical stasis … things changed. But things always change” (3-4, 12-3). As we’ll see, I don’t entirely disagree with those statements, but they are absolute to a degree that suggests there is no real challenge to the position. There have been a few cracks in this orthodoxy among medievalists, particularly the work of Robin Flemming (a revision, not a clear break, to be sure), to which we’ll return, but the cracks have been relatively few.

While some ancient historians also bought into this view, purchase there has always been uneven and seems, to me at least, now to be waning further. Instead, a process of what James O’Donnell describes as a “counter-reformation” (which he stoutly resists with his own The Ruin of the Roman Empire; O’Donnell is a declared reformer) is well underway, a response to the “change and continuity” narrative which seeks to update and defend the notion that there really was a fall of Rome and that it really was quite bad actually. This is not, I should note, an effort to revive Gibbon per se; it does not typically accept his understanding of the cause of this decline (and often characterizes exactly what is declining differently). Nevertheless, this position too is sometimes termed the “decline and fall” school. My own sense of the field is that while nearly all ancient historians will feel the need to concede at least some validity to the reformed “change and continuity” vision, that the counter-reformation school is the majority view among ancient historians at this point (in a way that is particularly evident in overview treatments like textbooks or the Cambridge Ancient History (second edition)). We’ll meet many of the core works of this revised “decline and fall” school as we go.

As O’Donnell noted in a 2005 review for the BMCR, the reformed school tends to be strongest in the study of the imperial east rather than the west (something that will make a lot of sense in a moment), and in religious and cultural history; the counter-reformation school is stronger in the west than the east and in military and political history, though as we’ll see, to that list must at this point now be added archaeology along with demographic and economic history, at which point the weight of fields tends to get more than a little lopsided.

Those are our two knights – the “change and continuity” knight and the “decline and fall” knight (and our old man Gibbon, long out of his dueling days). To this we must add the nitwit: a popular vision, held by functionally no modern scholars, which represents the Middle Ages in their entirety as a retreat from a position of progress during the Roman period which was only regained during the “Renaissance” (generally represented as a distinct period from the Middle Ages) which then proceeded into the upward trajectory of the early modern period. Intellectually, this vision traces back to what Renaissance thinkers thought about themselves and their own disdain for “medieval” scholastic thinking (that is, to be clear, the thinking of their older teachers), a late Medieval version of “this ain’t your daddy’s rock and roll!”

But almost every intellectual movement represents itself as a radical break with the past (including, amusingly, many of the scholastics! Let me tell you about Peter Abelard sometime); as historians we do not generally accept such claims uncritically at face value. For a long time, well into the 19th century, the Renaissance’s cultural cachet in Europe (and the cachet of the classical period where it drew its inspiration) shielded that Renaissance claim from critique; that patina now having worn thin, most scholars now reject it, positioning the Renaissance as a continuation (with variations on the theme) of the Middle Ages, a smooth transition rather than a hard break. At the same time, knowledge of developments within the Middle Ages have made the image of one unbroken “Dark Age” untenable and made clear that the “upswing” of the early modern period was already well underway in the later Middle Ages and in turn had its roots stretching even deeper into the period. It is also worth noting here, that the term “Dark Age” has to do with the survival of evidence, not living conditions: the age was not dark because it was grim, it was dark because we cannot see it as clearly.

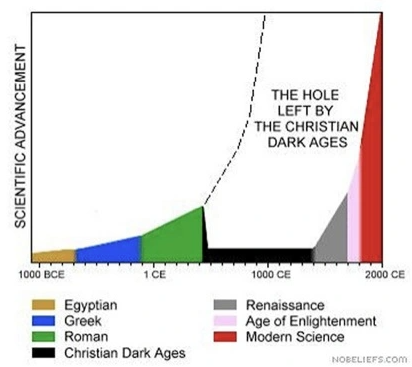

The popular version of this idea continues, however, to have a lot of sway in the popular conception of the Middle Ages, encouraged by popular culture that mistakes the excesses of the early modern period for “medieval” superstition and exaggerates the poverty of the medieval period (itself essentialized to its worst elements despite being approximately a millennia long), all summed up in this graph:

We are mostly going to just dunk relentlessly on this graph and yet we will not cover even half of the necessary dunking this graph demands. We may begin by noting that in its last century, the Roman Empire was Christian, a point apparently missed here.

While that sort of vision is not seriously debated by scholars, it needs to be addressed here too, in part because I suspect a lot of the energy behind the “change and continuity” position is in fact to counter some of the worst excesses of this thesis, which for simplicity, we’ll just refer to as “The Dung Ages” argument, but also because assessing how bad the fall of the Roman Empire in the West was demands that we consider how long-lasting any negative ramifications were.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

December 1, 2022

Medieval Table Manners

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 19 Jul 2022

(more…)

November 28, 2022

QotD: The Carolingian army

In essence, the Carolingian army was an odd sort of layer-cake, in part because it represented a transitional stage from the Germanic tribal levies of the earliest Middle Ages towards to emergence and dominance of the mounted aristocracy of the early part of the High Middle Ages (note: the Middle Ages is a long period, Europe is a big place, and it moves through a lot of military systems; to talk of a single “medieval European system” is almost always a dangerous over-generalization). The top of the layer-cake consisted of the mounted aristocrats, in basically the same organization as the lords of Rohan discussed above: the great magnates (including the king) maintained retinues of mounted warriors, while smaller (but still significant) landholders might fight as individual cavalrymen, being grouped into the retinues of the great magnates tactically, even if they weren’t subordinate to those magnates politically (although they were often both). These two groups – the mounted magnate with his retinue and the individual mounted warrior – would eventually become the nobility and the knightly class, but in the Carolingian period these social positions were not so clearly formed or rigid yet. We ought to understand that to speak of a Carolingian “knight” (translated for Latin miles, which ironically in classical Latin is more typically used of infantrymen) is not the same, in social consequence, as speaking of a 13th century knight (who might also be described as a miles in the Latin sources).

But below that in the Carolingian system, you have the select levy, relatively undistinguished (read: not noble, but often reasonably well-to-do) men recruited from the smaller farmers and townsfolk. This system itself seems to have derived from an earlier social understanding that all free men (or all free property owning men) held an obligation for military service; Halsall notes in the eighth century the term arimannus (Med. Lat.: army-man) or exercitalis (same meaning) as a term used to denote the class of free landowners on whom the obligation of military service fell in Lombard and later Frankish Northern Italy (the Roman Republic of some ten centuries prior had the same concept, the term for it was assidui). This was, on the continent at least, a part of the system that was in decline by the time of Charlemagne and especially after as the mounted retinues of the great magnates became progressively more important.

We get an interesting picture of this system in Charlemagne’s efforts in the first decades of the 800s to standardize it. Under Charlemagne’s system, productive land was assessed in units of value called mansi and (to simplify a complicated system) every four mansi ought to furnish one soldier for the army (the law makes provisions for holders of even half a mansus, to give a sense of how large a unit it was – evidently some families lived on fractions of a mansus). Families with smaller holdings than four mansi – which must have been most of them – were brigaded together to create a group large enough to be able to equip and furnish one man for the army. These fellows were expected to equip themselves quite well – shield, spear, sword, a helmet and some armor – but not to bring a horse. We should probably also imagine that villages and towns choosing who to send were likely to try to send young men in good shape for the purpose (or at least they were supposed to). Thus this was a draw-up of some fairly high quality infantry with good equipment. That gives it its modern-usage name, the select levy, because it was selected out of the larger free populace.

And I should note what makes these fellows different from the infantry who might often be found in the retinues of later medieval aristocrats is just that – these fellows don’t seem to have been in the retinues of the Carolingian aristocracy. Or at least, Charlemagne doesn’t seem to have imagined them as such. While he expected his local aristocrats to organize this process, he also sent out his royal officials, the missi to oversee the process. This worked poorly, as it turned out – the system never quite ran right (in part, it seems, because no one could decide who was in charge of it, the missi or the local aristocrats) and the decades that followed would see Carolingian and post-Carolingian rulers more and more dependent on their lords and their retinues, while putting fewer and fewer resources into any kind of levy. But Charlemagne’s last-gaps effort is interesting for our purpose because it illustrates how the system was supposed to run, and thus how it might have run (in a very general sense) in the more distant past. In particular, he seems to have imagined the select levy as a force belonging to the king, to be administered by royal officials (as the nation-in-arms infantry armies of the centuries before had been), rather than as an infantry force splintered into various retinues. In practice, the fragmentation of Charlemagne’s empire under his heirs was fatal for any hopes of a centralized army, infantry or otherwise, and probably hastened the demise of the system.

Beneath the select levy there was also the expectation that, should danger reach a given region, all free men would be called upon to defend the local redoubts and fortified settlements. This group is sometimes called the general levy. As you might imagine, the general levy would be of lower average quality and cohesion. It might include the very young and very old – folks who ought not to be picked out for the select levy for that reason – and have a much lower standard of equipment. After all, unlike select levymen, who were being equipped at the expense, potentially, of many households, general levymen were individual farmers, grabbing whatever they could. In practice, the general levy might be expected to defend walls and little else – it was not a field force, but an emergency local defense militia, which might either enhance the select levy (and the retinues of the magnates) or at least hold out until that field army could arrive.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Battle oF Helm’s Deep, Part IV: Men of Rohan”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-05-22.

November 12, 2022

Long distance communication in the pre-modern era

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers why the telegraph took so long to be invented and describes some of the precursors that filled that niche over the centuries:

… I’ve also long wondered the same about telegraphs — not the electric ones, but all the other long-distance signalling systems that used mechanical arms, waved flags, and flashed lights, which suddenly only began to really take off in the eighteenth century, and especially in the 1790s.

What makes the non-electric telegraph all the more interesting is that in its most basic forms it actually was used all over the world since ancient times. Yet the more sophisticated versions kept on being invented and then forgotten. It’s an interesting case because it shows just how many of the budding systems of the 1790s really were long behind their time — many had actually already been invented before.

The oldest and most widely-used telegraph system for transmitting over very long distances was akin to Gondor’s lighting of the beacons, capable only of communicating a single, pre-agreed message (with flames often more visible at night, and smoke during the day). Such chains of beacons were known to the Mari kingdom of modern-day Syria in the eighteenth century BC, and to the Neo-Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal in the seventh century BC. They feature in the Old Testament and the works of Herodotus, Aeschylus, and Thucydides, with archaeological finds hinting at even more. They remained popular well beyond the middle ages, for example being used in England in 1588 to warn of the arrival of the Spanish Armada. And they were seemingly invented independently all over the world. Throughout the sixteenth century, Spanish conquistadors again and again reported simple smoke signals being used by the peoples they invaded throughout the Americas.

But what we’re really interested in here are systems that could transmit more complex messages, some of which may have already been in use by as early as the fifth century BC. During the Peloponnesian War, a garrison at Plataea apparently managed to confuse the torch signals of the attacking Thebans by waving torches of their own — strongly suggesting that the Thebans were doing more than just sending single pre-agreed messages.

About a century later, Aeneas Tacticus also wrote of how ordinary fire signals could be augmented by using identical water clocks — essentially just pots with taps at the bottom — which would lose their water at the same rate and would have different messages assigned to different water levels. By waving torches to signal when to start and stop the water clocks (Ready? Yes. Now start … stop!), the communicator could choose from a variety of messages rather than being limited to one. A very similar system was reportedly used by the Carthaginians during their conquests of Sicily, to send messages all the way back to North Africa requesting different kinds of supplies and reinforcement, choosing from a range of predetermined signals like “transports”, “warships”, “money”.

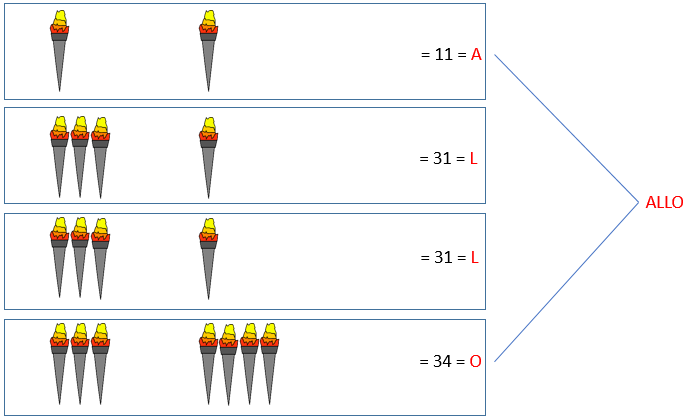

Diagram of a fire signal using the Polybius cipher.

Created by Jonathan Martineau via Wikimedia Commons.By the second century BC, a new method had appeared. We only know about it via Polybius, who claimed to have improved on an even older method that he attributed to a Cleoxenus and a Democleitus. The system that Polybius described allowed for the spelling out of more specific, detailed messages. It used ten torches, with five on the left and five on the right. The number of torches raised on the left indicated which row to consult on a pre-agreed tablet of letters, while the number of torches raised on the right indicated the column. The method used a lot of torches, which would have to be quite spread out to remain distinct over very long distances. So it must have been quite labour-intensive. But, crucially, it allowed for messages to be spelled out letter by letter, and quickly.

Three centuries later, the Romans were seemingly still using a much faster and simpler version of Polybius’s system, almost verging on a Morse-like code. The signalling area now had a left, right, and middle. But instead of signalling a letter by showing a certain number of torches in each field all at once, the senders waved the torches a certain number of times — up to eight times in each field, thereby dividing the alphabet into three chunks. One wave on the left thus signalled an A, twice on the left a B, once in the middle an I, twice in the middle a K, and so on.

By the height of the Roman Empire, fire signals had thus been adapted to rapidly transmit complex messages over long distances. But in the centuries that followed, these more sophisticated techniques seem to have disappeared. The technology appears to have regressed.

November 5, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 8 – The Breakdown, 1025-1204

seangabb

Published 20 May 2022In this, the eighth video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, having acquired the wrong sort of ruling class, the Byzantine Empire passed in just under half a century from the hegemonic power of the Near East to a declining hulk, fought over by Turks and Crusaders.

Subjects covered include:

The damage caused by a landed nobility

The deadweight cost of uncontrolled bureaucracy

The first rise of an insatiable and all-conquering West

The failure of the Andronicus Reaction

The sack of Constantinople in 1204Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

October 28, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 7 – Recovery and Return to Hegemony, 717-1025 AD

seangabb

Published 2 May 2022In this, the seventh video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, following the disaster of the seventh century, the Byzantine Empire not only survived, but even recovered its old position as hegemonic power in the Eastern Mediterranean. It also supervised a missionary outreach that spread Orthodox Christianity and civilisation to within reach of the Arctic Circle.

Subjects covered:

The legitimacy of the words “Byzantine” and “Byzantium”

The reign of the Empress Irene and its central importance to recovery

The recovery of the West and the Rise of the Franks

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire

The Conversion of the Russians – St Vladimir or Vladimir the Damned?

The reign of Basil IIBetween 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

(more…)

October 25, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 6 – Weathering the Storm, 628-717 AD

seangabb

Published 16 Feb 2022In this, the sixth video in the series, Sean Gabb discusses the impact on the Byzantine Empire of the Islamic expansion of the seventh century. It begins with an overview of the Empire at the end of the great war with Persia, passes through the first use of Greek Fire, and ends with a consideration of the radically different Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

October 12, 2022

History’s Real Macbeth

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 11 Oct 2022

(more…)

October 11, 2022

QotD: The debt we owe to the Carolingian Renaissance

The importance of the Carolingian Renaissance for text-preservation, by the by, is immediately relevant to anyone who has looked at almost any manuscript tradition: the absolute crushing ubiquity of Caroline minuscule, the standard writing form of the period, is just impossible to ignore (also, I love the heck out of Caroline minuscule because it is easy to both read and write – which is why it was so popular in this period; an unadorned, practical script – I love it; it’s the only medieval script I can write in with any meager proficiency). The sudden burst of book-copying tends to mean – for ancient works, at least, that if they survived to c. 830, then they probably survive to the present. Sponsored by Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, the scribes of the Carolingian period (mostly monks) rescued much of the Latin classical corpus we now have from oblivion. It is depressingly common to hear “hot-takes” or pop-culture references to how the “medievals” or the Church were supposedly responsible for destroying literature or ancient knowledge (this trope runs wild in Netflix’s recent Castlevania series, for instance) – the reverse is true. Without those 9th century monks, we’d probably have about as much Latin literature as we have Akkadian literature: not nothing, but far, far less. Say what you will about the medieval Church, you cannot blame the loss of the Greek or Roman tradition on them.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: A Trip Through Dhuoda of Uzès (Carolingian Values)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-27.

September 21, 2022

The Medieval Saint Diet

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 20 Sep 2022

(more…)

September 3, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 1 – Beginnings

seangabb

Published 1 Oct 2021Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 30, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 10 – The Vikings and the End of the Invasions

seangabb

Published 5 Sep 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the western provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 28, 2022

Jersey – Millennia of Maritime Defence Preserved

Drachinifel

Published 4 May 2022Today we take a look at the island of Jersey, part of the Channel Islands off the coast of France, to examine the many generations of maritime defence that have been built and upgraded there.

It’s an excellent place to visit! https://www.jersey.com/

(more…)