Thersites the Historian

Published 26 Oct 2017In this video, I try to bring order to the chaos that is feudalism and render it comprehensible.

April 29, 2020

Feudalism: A Brief Explanation

April 25, 2020

History-Makers: Shakespeare

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 24 Apr 2020“The Bard” is not only an essential class in any D&D party, but a byword for England’s most famous writer. We’ve covered a bit of Shakespeare before on OSP — just a bit, really, nothing major, only a dozen — but today we’ll look at how William got to Bard-ing, and how he accidentally became England’s biggest Historian.

SOURCES and Further Reading: The Introduction and play-texts of the Folger Shakespeare Library (The best way to read Shakespeare), “Shakespeare: A Very Short Introduction” by Wells

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/h3AqJPe

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

April 13, 2020

QotD: Foucault’s “Ship of Fools”

And so, Foucault tells us, in the fifteenth century there is a sudden emergence of a complex of artistic and philosophical themes linking madmen, the sea, and the terrible mysteries of the world. These culminate in the “Ship Of Fools”:

Renaissance men developed a delightful, yet horrible way of dealing with their mad denizens: they were put on a ship and entrusted to mariners because folly, water, and sea, as everyone then knew, had an affinity for each other. Thus, “Ships of Fools” crisscrossed the seas and canals of Europe with their comic and pathetic cargo of souls. Some of them found pleasure and even a cure in the changing surroundings, in the isolation of being cast off, while others withdrew further, became worse, or died alone and away from their families. The cities and villages which had thus rid themselves of their crazed and crazy, could now take pleasure in watching the exciting sideshow when a ship full of foreign lunatics would dock at their harbors.

This was such a great piece of historical trivia that I was shocked I’d never heard it before. Some quick research revealed the reason: it is completely, 100% false. Apparently Foucault looked at an allegorical painting by Hieronymus Bosch, decided it definitely existed in real life, and concocted the rest from his imagination.

Foucault apologists try to rescue this, say that he was just being poetic in some way. He wasn’t. Page 8 in my copy: “Of all these romantic or satiric vessels, the Narrenschiff [Ship Of Fools] is the only one that had a real existence — for they did exist, these boats that conveyed their insane cargo from town to town.” He really, really doubled down on this point. As far as I can tell, this is just as bad a failing of scholarship as it sounds – and surprising, since everything else about the book gives the impression of Foucault as an incredibly knowledgeable and wide-ranging scholar.

Scott Alexander, “Book review: Madness and Civilization”, Slate Star Codex, 2018-01-04.

March 18, 2020

A classic “dirty book” of the late Middle Ages

I’m not well read in the classics, being much more of a history reader myself, so I didn’t know anything about The Decameron. Arthur Chrenkoff provides a helpful thumbnail of the book:

“A Tale from the Decameron” by John William Waterhouse (1916).

Image from the Lady Lever Art Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

Giovanni Boccaccio had written The Decameron in the aftermath of the Black Death pandemic of 1348, which carried away somewhere around one third of the European population. The book is set in a monastery, where seven young women and three young men, the Millennials of the day, self-quarantine themselves for ten days to avoid the plague and while away their days (there was no internet in those days, you see) telling each other stories, ten each day, all based around a chosen theme, such as love that ends happily or the tricks that women play on men. Many of the stories are a bit dirty, which is why The Decameron was put on the Catholic Church’s index of prohibited books; more interestingly, it was also banned in Australia until 1973, on pretty similar grounds.

March 2, 2020

History-Makers: Anna Komnena

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 28 Feb 2020She’s a Princess! She’s a Poet! She’s a Historian! She’s Anna Komnena — the COOLEST writer in the Byzantine Empire! On this episode of History-Makers, jump into the reign of Alexios Komnenos from the perspective of his daughter Anna, and learn about the emperor who saved the Byzantines from certain doom, as well as the traits that make Anna’s Alexiad a masterpiece.

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi, AKA “Indigo”.

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.Sources & Further Reading: The Alexiad — obviously, what are you waiting for? (Also Norwich’s Byzantium)

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/h3AqJPe

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

March 1, 2020

The Black Death of the 14th Century

Ed West looks at what we know of the spread of the worst plague to hit western Europe in the 1300s:

Map showing the spread of the Black Death in Europe between 1346 and 1353.

Map by Flappiefh via Wikimedia Commons.

There had never been a terror like it, and the “Great Mortality” as it was known — and much later, the “Black Death” — has seared itself in the European imagination. It changed the culture and tested the institutions of the time, and as we anxiously await the arrival of another — thankfully far less deadly — contagion from Italy its legacy and impact are worth remembering.

Epidemics have been around as long as civilization. Plaga — from the Greek for “strike” or “hit” — devastated classical Athens in the 5th century BC, when the historian Thucydides nursed sufferers; the Antonine Plague — probably smallpox or measles — killed as many as five million Romans at the empire’s peak. Far more deadly was the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century, which had a toll of 25 million and emptied whole regions of the eastern (Byzantine) Empire. Only in the 21st century did researchers confirm that this was the same illness that would appear eight centuries later — the Bubonic Plague.

Empires were particularly affected by these horrific epidemics, because empires are a form of globalisation — bringing different people into contact with each other and, more dangerously, into contact with other mammals, who act as disease vectors.

Another danger is climate change, which might turn a mild virus into a deadly one, or cause disease-carrying animals to migrate. This is what happened during the 14th century when the northern hemisphere became considerably cooler, soon after the Mongols had created the largest contiguous empire in history.

Genghis Khan’s people have generally received a historical bad press — people are more likely to recall the pyramid of skulls and the Tigris flowing black and red — yet their rule had opened up trade routes, allowing goods and people to cross Asia. Whether brought at the point of a sword or a trade deal, globalisation always brings the new: new cultures, new ideas, new languages and new pathogens.

Yersinia pestis had been living on gerbils and other rodents in central Asia, but unstable climate conditions in 1330s caused the disease to jump onto the rat flea. It was killing people by 1339, and in the mid-1340s Christians first heard of a disease raging in the Islamic world, which some at least took as divine punishment for the crusades.

After two centuries of Holy War this was understandable, yet hatred was not universal and during these conflicts Italian merchants had continually done business with Muslims, much to the Church’s fury. Now this trade, once the source of prosperity and peace, proved deadly: plague reached Europe via the Genovese colony of Caffa on the Black Sea (now Feodosiya, in the Ukraine). In October 1347, four ships escaping the diseased city had turned up in Sicily, condemning Italy to its fate.

The rise and fall of the Byzantine Empire – Leonora Neville

TED-Ed

Published 9 Apr 2018Check out our Patreon page: https://www.patreon.com/teded

View full lesson: https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-rise-a…

Most history books will tell you that the Roman Empire fell in the fifth century CE, but this would’ve come as a surprise to the millions who lived in the Roman Empire through the Middle Ages. This Medieval Roman Empire, today called the Byzantine Empire, began when Constantine, the first Christian emperor, moved Rome’s capital. Leonora Neville details the rise and fall of the Byzantine Empire.

Lesson by Leonora Neville, animation by Remus & Kiki.

Thank you so much to our patrons for your support! Without you this video would not be possible! Abhijit Kiran Valluri, Mandeep Singh, Sama aafghani, Vinicius Lhullier, Connor Wytko, Marylise CHAUFFETON, Marvin Vizuett, Jayant Sahewal, Quinn Shen, Caleb ross, Elnathan Joshua Bangayan, Gaurav Rana, Mullaiarasu Sundaramurthy, Jose Henrique Leopoldo e Silva, Dan Paterniti, Jose Schroeder, Jerome Froelich, Tyler Yoshizumi, Martin Stephen, Justin Carpani, Faiza Imtiaz, Khalifa Alhulail, Tejas Dc, Govind Shukla, Srikote Naewchampa, Ex Foedus, Sage Curie, Exal Enrique Cisneros Tuch, Vignan Velivela, Ahmad Hyari, A Hundred Years, eden sher, Travis Wehrman, Minh Tran, Louisa Lee, Kiara Taylor, Hoang Viet, Nathan A. Wright, Jast3 , Аркадий Скайуокер, Milad Mostafavi, Singh Devesh Sourabh, Ashley Maldonado, Clarence E. Harper Jr., Bojana Golubovic, Mihail Radu Pantilimon, Sarah Yaghi, Benedict Chuah, Karthik Cherala, haventfiguredout, Violeta Cervantes, Elaine Fitzpatrick, Lyn-z Schulte, cnorahs, Henrique ‘Sorín’ Cassús, Tim Robinson, Jun Cai, Paul Schneider, Amber Wood, Ophelia Gibson Best, and Cas Jamieson.

February 20, 2020

So that’s why John Cabot got hired!

Anton Howes explains something that I’d wondered about in the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter:

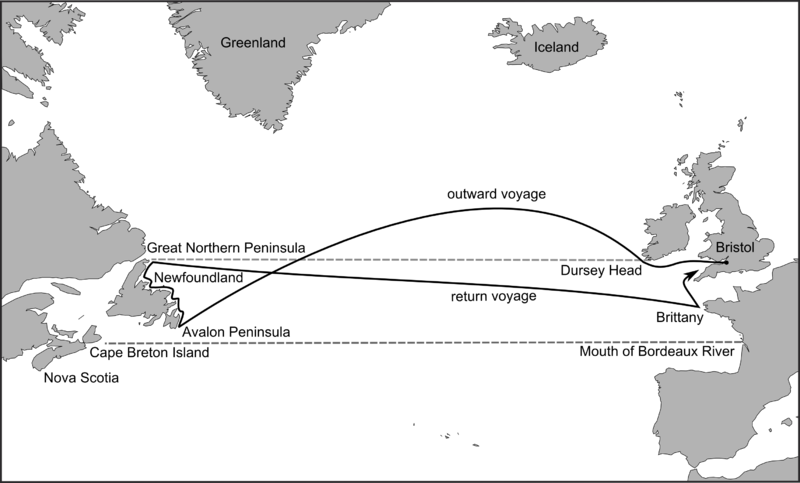

Route of John Cabot’s 1497 voyage on the Matthew of Bristol posited by Jones and Condon: Evan T. Jones and Margaret M. Condon, Cabot and Bristol’s Age of Discovery: The Bristol Discovery Voyages 1480-1508 (University of Bristol, Nov. 2016), fig. 8, p. 43.

Wikimedia Commons.

… in 1550 the English were still struggling with latitude. Their inability to find it, unlike their Spanish and Portuguese rivals, was one of the main things holding them back from voyages of exploration.

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.The traditional method of navigation for English pilots was to simply learn the age-old routes. They were trained through repetition and accrued experience, learning to recognise particular landmarks and using a lead and line – just a thin rope weighted with some lead – to determine their location from the depth of the water. Cover the lead with something sticky, and you might bring up some sediment from the sea floor to double-check: a pilot would learn the kinds of sand and pebbles from to expect from different areas. And when they travelled out to sea, away from the coastline, they used a basic system of dead reckoning, taking their compass bearings from a known location, estimating their speed, and keeping in a particular direction for long enough. Or at least hoping to. They might keep track of their progress on a wooden traverse table, inserting pegs to indicate how far they had sailed, but it was ultimately a matter of rough estimation. Should they make any mistake — in terms of their speed, heading, or point of departure — they might easily get lost. But it was still a matter of trying to follow an already-known route. And English mariners of the 1550s did not even know that many routes.

For a voyage of exploration, by contrast, landmarks and sediment from the sea floor would be seen for the first time rather than recalled. By definition, there was no route to follow. So to launch their own voyages of discovery, the English needed to learn a new skill. They needed to look to the heavens.

Celestial navigation — measuring the altitude of heavenly bodies and then using geometry to determine one’s latitude on the earth’s surface — was by the 1550s already hundreds of years old. It had primarily been used to cross the deserts of North Africa and the Middle East — seas of sand, in which there might also be no landmarks from which to take bearings — and to navigate the Indian Ocean. Thus, while pilots in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stuck to dead reckoning and soundings, Islamic navigators had for centuries used quadrants and astrolabes to take their bearings at sea. By the mid-fifteenth century, these instruments and techniques had found their way to Europe, where they were put to use especially by Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian explorers, along with additional instruments such as the cross-staff.

[…]

So for decades, English explorations relied on foreigners who either knew the routes that the English pilots didn’t, or who at least possessed the skill of mathematical, celestial navigation. The Italian explorer John Cabot (Zuan Chabotto), when he sailed to Newfoundland from Bristol in the late 1490s, was able to take latitude readings (he may even have been familiar with the older Islamic navigational practices, as he claimed to have visited Mecca). When Cabot died, the English expeditions that set out from Bristol in 1501-3 relied on Portuguese pilots from the mid-Atlantic islands of the Azores. And John Cabot’s son, Sebastian Cabot, who was involved in a few English expeditions, was so expert in mathematical navigation that he was eventually appointed pilot major for the entire Spanish Empire, making him responsible for the training and licensing of all its pilots — a position he held for three decades. When he led a voyage of exploration on behalf of Spain in 1526-30, a few English merchants became investors so that they could justify sending with him an English mariner, Roger Barlow, to secretly learn the Spanish routes across the Atlantic and have immediate knowledge if an onward route to Asia was discovered (as it turned out, South America got in the way).

February 17, 2020

Sieges and Siege-craft

Lindybeige

Published 2 Jun 2016Sieges in the ancient and medieval worlds were on quite different scales. 10,000 men can do things differently from 500.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

This video’s subject was chosen by Jack Sargeant, the winner of the DeepArt art competition a couple of weeks ago. The topic is a large one, but I hope I gave it a decent enough shot.

Castle illustration by Mathew Nielsen.

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

February 4, 2020

Anglo-Saxon Invasion | 3 Minute History

February 1, 2020

History Summarized: Byzantine Empire — The Golden Age

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 31 Jan 2020What do you do when life takes away half of your empire? Well, if you’re the Medieval Byzantines, you make comprehensive structural reforms to better manage a changing geopolitical landscape — And then you make an absolute crapload of mosaics.

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

This video was edited in part by Sophia Ricciardi, AKA “Indigo”.

FURTHER SOURCES: A Short History of Byzantium by John Julius Norwich.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/h3AqJPe

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

January 30, 2020

QotD: Nutrition and aging from the middle ages to the 20th century

Those of us who didn’t grow up in the first world (second and a half at best!) know d*mn well how people lived in the 20th century, with nominal indoor plumbing, but without a lot of changes of clothing, washers and dryers, heated houses, etc. (The trains from the mountains, where it was colder, in winter, smelled like a mix of VERY unwashed bodies and wood smoke. You never forget that smell.) The particular etc. I have in mind in this case is the lack of refrigeration.

Look Portugal is fertile enough that a careful planner can feed a family on less than an acre of land (particularly the area I come from, apparently one of the oldest inhabited in Europe and whose name in Indo European translated as wet and fertile valley.) I’m sure the food available to us in the 20th century when you could buy improved seeds, etc. was way better than the one available to people in the middle ages.

But … yeah, no. We didn’t eat like people do now. Not even close. For one, meat was fairly scarce. We mostly ate fish (thanks to the coasts!) and vegetables. Oh, and we were relatively lucky. A lot of people got almost no protein. The most common lunch among the people was the “isca” that is a bit of fried flour which might or might not have a couple of shreds of codfish in it. The very poor ate a lot of vegetable soup.

And again this was in the 20th century. In winter vegetables more or less vanished and the only fruit available were the wrinkled, flour-like apples.

Christmas treats were dried fruit, not cookies. It tells you all you need to know. (Yes, it was healthy too except for the scarce protein for most people, but no one said the way we eat is particularly healthy.)

I’m not complaining, but I know that we ate massively better than my parents did in the mid 20th century. And they ate better than their parents. So, kindly, do not tell me some serf on a medieval estate got his choice of however many flavors of ice-cream.

Sure the very rich ate well, if sometimes oddly. But the average person, not so much.

And as for living as long? Yeah, no.

I still remember vividly — as do many our age — when 60 was old, 70 VERY old.

Yes, I’m concerned for my parents in their late eighties. And that’s, as my dad puts it “after 80, that’s old”. But it would surprise no one is they lived another 10 years. Because a lot of people do now. And now one makes a big deal of people who turn 100. (Even though 114 seems to be, a little inexplicably, our hard drop-off limit.)

And besides we KNOW. Shakespeare at 58 — two years older than I’m now — was “very old.”

So kindly take your “people lived about as long,” fold it all in corners and put it where the sun don’t shine, even if people in the arctic in winter will be a little puzzled by it.

Sarah Hoyt, “What if I Told You?”, According to Hoyt, 2019-11-05.

January 18, 2020

History Summarized: Classical India

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 17 Jan 2020Classical and Medieval Indian History is a tale of constant flux — but in between the dozens and hundreds of states at play across the peninsula, there are clear trends that arise. Let’s take this chapter of history as an opportunity to dig into different types of sources, and try and wrap our heads around a story that doesn’t fit neatly into a single chronology.

FURTHER SOURCES: The Discovery of India by Jawaharlal Nehru, “A History of India” by Michael H. Fisher (lecture courtesy of The Great Courses).

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/y7uUnzJ

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

January 15, 2020

Hundred Years’ War: Battle of Crecy 1346

Kings and Generals

Published 7 December 2017The Hundred Years’ War of 1337-1453 between France and England is one of the most crucial conflicts in the history of Europe. It changed the social, political and cultural outlook of the countries involved, influenced the change in warfare, brought the end of feudalism closer. The first phase of this war is called the Edwardian War, and one of the most decisive engagements of this conflict was the battle of Crecy (1346). This series will have 5 videos, so don’t hesitate to like, subscribe and share. And if you want to support us, you can do it on Patreon: http://www.patreon.com/KingsandGenerals or Paypal: http://paypal.me/kingsandgenerals

We are grateful to our patrons, who made this video possible: Ibrahim Rahman, Koopinator, Daisho, Łukasz Maliszewski, Nicolas Quinones, William Fluit, Juan Camilo Rodriguez, Murray Dubs, Dimitris Valurdos, Félix Gagné-Dion, Fahri Dashwali, Kyle Hooton, Dan Mullen, Mohamed Thair, Pablo Aparicio Martínez, Iulian Margeloiu, Chet, Nick Nasad, Jeyares, Amir Eppel, Thomas Bloch, Uri Sternfeld, Juha Mäkelä, Georgi Kirilov, Mohammad Mian, Daniel Yifrach, Brian Crane, Muramasa, Gerald Tnay, Hassan Ali, Richie Thierry, David O’Hare, Christopher Commins, Chris Glantzis, Mike, William Pugh, Stefan Dt, indy, Bashir Hammour, Mario Nickel, R.G. Ferrick, Moritz Pohlmann, Russell Breckenridge, Jared R. Parker, Kassem Omar Kassem, AmericanPatriot, Robert Arnaud, Christopher Issariotis, John Wang, Joakim Airas, Nathanial Eriksen and Joakim Airas.

This video was narrated by our good friend Officially Devin. Check out his channel for some kick-ass Let’s Plays. https://www.youtube.com/user/Official…

The Machinimas for this video is created by one more friend – Malay Archer. Check out his channel, he has some of the best Total War machinimas ever created: https://www.youtube.com/user/Mathemed…

Inspired by: BazBattles, Invicta (THFE), Epic History TV, Historia Civilis and Time Commanders

Machinimas made on the Total War: Attila engine using the great Medieval Kingdoms mod.

Production Music courtesy of Epidemic Sound: http://www.epidemicsound.com

January 7, 2020

Wars of the Roses | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 23 Jan 2015Of course there’s a lot I left out.

And when I say “Lancaster”, it sounds out of place because I had to just record over me continuously saying “Lancashire”.