seangabb

Published 1 Oct 2021Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 3, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 1 – Beginnings

August 30, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 10 – The Vikings and the End of the Invasions

seangabb

Published 5 Sep 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the western provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 28, 2022

Jersey – Millennia of Maritime Defence Preserved

Drachinifel

Published 4 May 2022Today we take a look at the island of Jersey, part of the Channel Islands off the coast of France, to examine the many generations of maritime defence that have been built and upgraded there.

It’s an excellent place to visit! https://www.jersey.com/

(more…)

August 25, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 8 – The Franks

seangabb

Published 1 Sep 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 20, 2022

QotD: The improbable survival of the Byzantine empire

The [Eastern Roman] Empire was faced by a triple threat to its existence. There were the northern barbarians. There was militant Islam in the south. There was an internal collapse of population. Each of these had been brought on by changes in the climate that no one at the time could have understood had they been noticed. It would not be until after 800 that the climate would turn benign again. In the meantime, any state to which even a shadow of Lecky’s dismissal applied would have crumpled in six months. Only the most courageous and determined action, only the most radical changes of its structure, could save the Empire. And saved the Empire most definitely was.

The reason for this is that the Mediaeval Roman State was directed by creative pragmatists. Look for one moment beneath its glittering surface, and the Ancient Roman Empire was a ghastly place for most of the people who lived in it. The Emperors at the top were often vicious incompetents. They ruled through an immense and parasitic bureaucracy. They were supreme governors of an army too large to be controlled. They protected a landed aristocracy that was a repository of culture, but that was ruthless in its exaction of rent. Most ordinary people were disarmed tax-slaves, where not chattel slaves or serfs.

The contemporary historians themselves are disappointingly vague about the seventh and eighth centuries. Our only evidence for what happened comes from the description of established facts in the tenth century. As early as the seventh century, though, the Mediaeval Roman State pulled off the miracle of reforming itself internally while fighting a war of survival on every frontier. Much of the bureaucracy was shut down. Taxes were cut. The silver coinage was stabilised. Above all, the senatorial estates were broken up and given to those who worked on them, in return for service in local militias. Though never abolished, chattel slavery became far less pervasive. The civil law was simplified, and the criminal law humanised – after the seventh century, as said, the death penalty was rarely used.

The Mediaeval Roman Empire survived because of a revolutionary transformation in which ordinary people became armed stakeholders. The inhabitants of Roman Gaul and Italy and Spain barely looked up from their ploughs as the Barbarians swirled round them. The citizens of Mediaeval Rome fought like tigers in defence of their country and their Orthodox faith. Time and again, the armies of the Caliph smashed against a wall of armed freeholders. This was a transformation pushed through in a century and a half of recurrent crises during which Constantinople itself was repeatedly under siege. Alone among the ancient empires in its path, Mediaeval Rome faced down the Arabs, and kept Islam at bay for nearly five centuries. Would it be superfluous to say that no one does this by accident?

Sean Gabb, “The Mediaeval Roman Empire: An Unlikely Emergence and Survival”, SeanGabb.co.uk, 2018-09-14.

July 26, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 4 – The Ostrogoths in Italy

seangabb

Published 10 May 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western Provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

July 22, 2022

Winemaking in the Middle Ages | The Process, Taste, Storage and Use

Kobean History

Published 31 Aug 2020

(more…)

July 21, 2022

QotD: The history of the self-portrait

Consider the history of the self-portrait. The Wiki summary is interesting (and unintentionally hilarious. They have a whole section on women artists, because of course they do, which starts thusly: “Women artists are notable producers of self-portraits.” Gee, ya think? That has to be my favorite Alanis-level irony, that the SJWs’ constant attempts to pump up their favorite “underrepresented groups” always end up confirming everything we Deplorables say about those groups). Artists have inserted “themselves” into their works from antiquity, it seems, but as minor background figures. The self-portrait as a standalone work of art — that is, as a piece of art to be appreciated strictly on its own technical merits — was pioneered, as far as we know, by van Eyck.

Severian, “As I Can”, Founding Questions, 2022-04-18.

July 20, 2022

Climate change is nothing new, and it was warmer in England for a few hundred years in the Middle Ages

If you’ve been reading the blog for a while, you’ll have noticed that I’m not a fan of trying to panic people about climate change … catastrophism just isn’t my thing. I certainly don’t deny that climate change happens and I agree that it is happening now, but I’m highly skeptical that human action has more than a minor influence compared to the ups and downs of long-term climate shifts driven by natural forces. Ed West has a thumbnail sketch of just how much the European (and especially English) climate change impacted ordinary people during the Middle Ages:

Chart from the Journal of Quaternary Science Reviews showing Greenland ice core data over the last 10,000 years. At the end of the Minoan Warming came the Bronze Age Collapse, after the Roman Warming came the fall of the western Roman Empire.

The climate is changing, with all that entails, something we’ve known about for several decades now. Among the early proponents of the theory of climate change was mid-century climatologist Hubert Lamb, who spent most of his career at the Met Office and during the course of his studies made a curious historical discovery.

It was once widely believed that climate remained relatively stable over recorded history, civilisational lifespans being too brief to see such grand changes. But while looking into medieval chroniclers, Lamb was struck by the numerous references to vineyards in England, some as far as the midlands. As long as anyone had ever remembered, the country had been too cold to grow wine, except in tiny pockets of Sussex which occasionally produced almost-drinkable white.

William of Malmesbury, living in the 12th century, observed of his native Wiltshire that “in this region the vines are thicker, the grapes more plentiful and their flavour more delightful than in any other part of England. Those who drink this wine do not have to contort their lips because of the sharp and unpleasant taste, indeed it is little inferior to French wine in sweetness.” How could that have been?

Lamb concluded that Europe must have been considerably warmer during the Middle Ages, and in 1965 produced his great study outlining the theory of the Medieval Warm Period; this posited that Europe was at its hottest in the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) and then became unusually cool between 1500 and 1700.

Since then, Lamb’s thesis has been reinforced by analysis of pollen in peat bogs, as well as the radioactive isotope Carbon-14 found in tree rings (the less sun, the more Carbon-14). In Medieval Europe, every summer was a hot girl summer — and tiny changes could make earth-shattering differences.

The people of Europe enjoyed that extended period of warmer weather for about 300 years, then things suddenly got far worse:

Across Europe, people must have noticed a change. Farmers in the Saastal Valley in Switzerland were probably the first to observe what was happening, back in the 1250s, when the Allalin Glacier began to flow down the mountain. Surviving plant material from Iceland suggests an abrupt decrease in the temperature from 1275 — and, as Rosen points out, a reduction of one degree made a harvest failure seven times more likely. From 1308 England saw four cold winters in succession; the Thames froze, chroniclers recalling dogs chasing rabbits across the icy surface for the first time.

As with many things, change was gradual, until it was dramatic, for then came the disastrous year of 1315. The Chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis, written by a monk at the Abbey of Saint-Denis outside Paris, recorded that in April the rains came down hard — and didn’t stop until August.

Drenched and starved of sunlight, the crops failed across Europe. The price of food doubled and then quadrupled. By May 1316, crop production in England was down by up to 85 percent and there was “most savage, atrocious death”, as a chronicler put it. Hopeless townsfolk walked into the countryside, searching for any bits of food; men wandered across the country to work, only to return and find their wives and children dead from starvation. At one point, on the road near St Albans, no food could be found even for the king. Emaciated bodies could be seen floating face down in flooded fields.

The Great Famine killed anywhere between 5-12% of the European population, although some areas, such as Flanders, suffered far worse death rates, losing up to a quarter of their population to hunger.

July 6, 2022

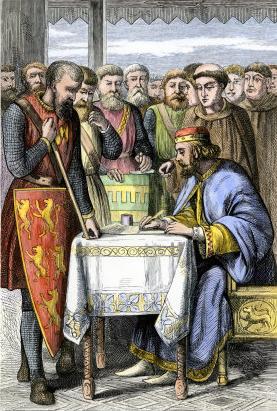

“The Great Charter of the Liberties” was signed on June 15, 1215 at Runnymede

Ed West on the connections between England’s Magna Carta and the American system (at least before the “Imperial Presidency” and the modern administrative state overwhelmed the Republic’s traditional division of powers):

King John signs Magna Carta on June 15, 1215 at Runnymede; coloured wood engraving, 19th century.

Original artist unknown, held by the Granger Collection, New York. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

England does not really go in for national monuments, and when it does they are often eccentric. There is no great shrine to Alfred the Great, for example, the great founder of our nation, but we do have, right in the middle of London, a large marble memorial to the animals that gave their lives in the fight against fascism. And Runnymede, which you could say is the birthplace of English liberty, would be a deserted lay-by were it not for the Americans.

Beside the Thames, some 10 miles outside London’s western suburbs, this place “between Windsor and Staines”, as it is called in the original document, is a rather subdued spot, with the sound of constant traffic close by. Once there you might not know it was such a momentous place were it not for an enclosure with a small Romanesque circus, paid for by the American Association of Lawyers in 1957.

American lawyers are possibly not the most beloved group on earth, but it would be an awful world without them, and for that we must thank the men who on June 15, 1215 forced the king of England to agree to a document, “The Great Charter of the Liberties”.

Although John went back on the agreement almost immediately, and the country fell into civil war, by the end of the century Magna Carta had been written into English law; today, 800 years later, it is considered the most important legal document in history. As the great 18th-century statesman William Pitt the Elder put it, Magna Carta is “the Bible of the English Constitution”.

It was also, perhaps more importantly to the world, a huge influence on the United States. That is why today the doors to America’s Supreme Court feature eight panels showing great moments in legal history, one with an angry-looking King John facing a baron in 1215.

Magna Carta failed as a peace treaty, but after John’s death in 1216 the charter was reissued the following year, an act of desperation by the guardians of the new boy king Henry III. In 1300 his son Edward I reconfirmed the Charter when there was further discontent among the aristocracy; the monarch may have been lying to everyone in doing so, but he at least helped establish the precedent that kings were supposed to pretend to be bound by rules.

From then on Parliament often reaffirmed Magna Carta to the monarch, with 40 such announcements by 1400. Clause 39 heavily influenced the so-called “six statutes” of Edward III, which declared, among other things, that “no man, of whatever estate or condition he may be … could be dispossessed, imprisoned, or executed without due process of law”, the first time that phrase was used.

Magna Carta was last issued in 1423 and then barely referenced in the later 15th or 16th centuries, with the country going through periods of dynastic fighting followed by Tudor despotism and religious conflict. By Elizabeth I’s time, Magna Carta was so little cared about that Shakespeare’s play King John didn’t even mention it.

June 24, 2022

“… most of the ‘mental health crisis’ is just loneliness”

Ed West believes we’re suffering so many social ailments because we’re social creatures, evolutionarily speaking, and modern society has reduced or eliminated so many traditional community social gatherings — made far, far worse by arbitrary lockdown rules and harsh enforcement during the Wuhan Coronavirus panicdemic. He’s talking specifically about Britain and Europe, but the same definitely applies here in North America:

“Procession for Corpus Christi” attributed to Master of James IV of Scotland (Flemish, before 1465 – about 1541), illuminator.

Original illumination in the Getty Center Collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week, for example, most of continental Europe got a holiday to mark Corpus Christi, once a huge event in England but killed off by the Reformation. Why can’t we have a holiday too? It was 27 degrees in London last Thursday — it would have been great.

We’re all aware, on some subconscious level, that there is a need for communal feasts and holidays, and in some ways the idea of a June procession to celebrate the official religion has made a comeback with Pride. The feast-shaped hole in our lives is why, from time to time, the great and the good come up with very boring ideas for substitutes feasts, the latest being “Celebration Day”. The idea is for “one day in the year when we can all take a pause in our busy lives to reflect, remember and celebrate the lives of people no longer here”. You mean, like the feast of All Saints’ and All Souls’, which again was a huge part of our calendar once and is still marked in Catholic countries? Like that one?

[…]

Contrary to the fashionable Noughties takes about the evils of supernatural belief, religion has huge psychological benefits. There is a vast array of evidence showing that attending religious ceremonies increases dopamine responses in the brain. Overcoming our fear of death is not even the key part; it is meeting other people and taking part in a common ritual, which has huge benefits, including reduced risk of suicide or addiction. Religious attendance is “associated with lower psychological distress” and “related to higher well-being”.

Modernity, diet and substance abuse may have slightly increased rates of extreme mental illness such as schizophrenia, while social media has allowed people with personality disorders to become prevalent, especially in politics. But most of the “mental health crisis” is just loneliness. People attend fewer communal events because of the decline of religion, they see other people less regularly and they have fewer friends — of course they’re unhappy! Humans are not just social mammals, we are ultra-social by the standards of other species; that’s why we need common rituals and why we’re chasing that religious feeling everywhere and can’t find it. It is why, as Madeline Grant wrote in the Telegraph this week, that as well as progressive institutions adopting religious-type feasts, even exercise classes increasingly resemble Mass.

Lockdown, traumatic though it was, was merely an extreme version of the trend towards solitude already underway (with working from home, online shopping and various other lockdown activities on the rise before 2020). Most traditional societies would consider our everyday lives in non-Covid times to be a form of lockdown, with historically very unusual levels of isolation. That is why the extreme loneliness of lockdown gave rise to ersatz rituals such as Clap for Carers.

Yet you just can’t beat the real thing. As Parker wrote at the time, ritual decline was a real sadness in our lives: “From the Middle Ages until the first half of the 20th century, Whitsun and the week that followed was the chief summer holiday of the year in Britain. It was a time for all kinds of communal merry-making, varying over the centuries but consistent in spirit: the season for feasts and fairs, dancing and drinking, school and church processions, and generally having a good time.”

June 7, 2022

History of Rome in 15 Buildings 12. Santa Maria in Trastevere

toldinstone

Published 2 Oct 2018Wanted: candidate for Pope. Must be a good fundraiser, effective administrator, and shrewd politician. Deep pockets a must. Sanctity negotiable.

The medieval papacy lies at the heart of this twelfth episode of our History of Rome, in which we discuss the catastrophic schism that created the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere.

To see the story and photo essay associated with this video, go to:

https://toldinstone.com/santa-maria-i…

June 3, 2022

The Crusades: Part 10 – The End of the Crusader Kingdoms

seangabb

Published 27 Mar 2021The Crusades are the defining event of the Middle Ages. They brought the very different civilisations of Western Europe, Byzantium and Islam into an extended period of both conflict and peaceful co-existence. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this long encounter with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

May 31, 2022

The Crusades: Part 9 – The Other Crusades

seangabb

Published 18 Mar 2021The Crusades are the defining event of the Middle Ages. They brought the very different civilisations of Western Europe, Byzantium and Islam into an extended period of both conflict and peaceful co-existence. Between January and March 2021, Sean Gabb explored this long encounter with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

History of Rome in 15 Buildings 11. Santa Prassede

toldinstone

Published 2 Oct 2018After Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor in 800, Europe had two notional leaders: the pope and the emperor. In theory, they were the twin pillars of a well-ordered Christian society. In practice, they were usually at each other’s throats. One product of their rivalry was the ninth-century church of Santa Prassede, the subject of this eleventh episode in our history of Rome.

To see the story and photo essay associated with this video, go to:

https://toldinstone.com/santa-prassede/