Because French was at that time the international language of trade, it acted as a conduit, sometimes via Latin, for words from the markets of the East. Arabic words that it then gave to English include: “saffron” (safran), “mattress” (materas), “hazard” (hasard), “camphor” (camphre), “alchemy” (alquimie), “lute” (lut), “amber” (ambre), “syrup” (sirop). The word “checkmate” comes through the French “eschec mat” from the Arabic “Sh h m t“, meaning the king is dead. Again, as with virtue and as with hundreds of the words already mentioned, a word, at its simplest, is a window. In that case, English was perhaps as much threatened by light as by darkness, as much in danger of being blinded by these new revelations as buried under their weight.

Yet the best of English somehow managed to avoid both these fates. It retained its grammar, it held on to its basic words, it kept its nerve, but what it did most remarkably was to accept and absorb French as a layering, not as a replacement but as an enricher. It had begun to do that when Old English met Old Norse: hide/skin; craft/skill. Now it exercised all its powers before a far mightier opponent. The acceptance of the Norse had been limited in terms of vocabulary. Here English was Tom Thumb. But it worked in the same way.

So, a young English hare came to be named by the French word “leveret“, but “hare” was not displaced. Similarly with English “swan”, French “cygnet“. A small English “axe” is a French “hatchet“. “Axe” remained. There are hundreds of examples of this, of English as it were taking a punch but not giving ground.

More subtle distinctions were set in train. “Ask” – English – and “demand” – from French – were initially used for the same purpose but even in the Middle Ages their finer meanings might have differed and now, though close, we use them for markedly different purposes. “I ask you for ten pounds”; “I demand ten pounds”: two wholly different stories. But both words remained. So do “bit” and “morsel”, “wish” and “desire”, “room” and “chamber”. At the time the French might have expected to displace the English. It did not and perhaps the chief reason for that is that people saw the possibilities of increasing clarity of thought, accuracy of expression by refining meaning between two words supposed to be the same. On the surface some of these appear to be interchangeable and sometimes they are. But much more interesting are these fine differences, whose subtleties increase as time carries them first a hair’s breadth apart and then widens the gap, multiplies the distinctions: just as “ask” has evolved far away from “demand”.

Not only did they drift apart but something else happened which demonstrates how deeply not only history but class is buried in language. You can take an (English) “bit” of cheese and most people do. If you want to use a more elegant word you take a (French) “morsel” of cheese. It is undoubtedly thought to be a better class of word and yet “bit”, I think, might prove to have more stamina. You can “start” a meeting or you can “commence” a meeting. Again, “commence” carries a touch more cultural clout though “start” has the better sound and meaning to it for my ear. But it was the embrace which was the triumph, the coupling which was never quite one.

That’s the beauty of it. That was the sweet revenge which English took on French: it not only anglicised it, it used the invasion to increase its own strength; it looted the looters, plundered those who had plundered, out of weakness brought forth strength. For “answer” is not quite “respond”; now they have almost independent lives. “Liberty” isn’t always “freedom”. Shades of meaning, representing shades of thought, were massively absorbed into our language and our imagination at that time. It was new lamps and old; both. The extensive range of what I would call “almost synonyms” became one of the glories of the English language, giving it astonishing precision and flexibility, allowing its speakers and writers over the centuries to discover what seemed to be exactly the right word.

Rather than replace English, French was being brought into service to help enrich and equip it for the role it was on its way to reassuming.

Melvyn Bragg, The Adventure of English, as quoted by Brian Micklethwait, “Melvyn Bragg on England’s verbal twins”, Samizdata, 2018-12-23.

July 21, 2021

QotD: The expansion of the English vocabulary (through plundering French)

July 16, 2021

The lure of London and agricultural specialization in post-Black Death England

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the “push” and “pull” theories to account for the vast growth of London and how that urban growth strongly encouraged specialization in English agriculture to feed the great city:

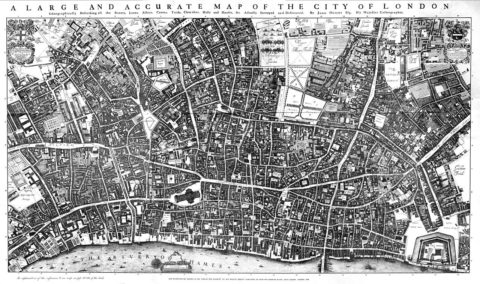

The 1677 original of this map is 8 feet 5 inches by 4 feet 7 inches, in 20 sheets. In 1894 the British Museum granted permission to the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society to make a reduced copy, of which the original of this scan is a copy. The L&M Society copy apparently did not match the dissected sheets perfectly, and the misjoins can be seen in places in this reproduction.

Scanned copy of reproduction in Maps of Old London (1908) of Ogilby & Morgan’s Map of London.

Something significant happened to the English countryside in the century before 1650. Although England’s population merely recovered to its pre-Black Death high of about 5 million, the economy was transformed. Having once been an overwhelmingly agrarian society, by 1650 a small but unprecedented proportion of the population now lived in cities, and less than half of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The country had de-agrarianised, and most remarkably of all, its food was still grown at home.

[…]

One possibly explanation is that there was some special change in England’s agricultural technology that increased its productivity, requiring fewer and fewer people, and possibly even driving them off the land, so that they were forced to find alternative employment. This thesis comes in various forms, many of which I’m still coming to grips with, but broadly speaking it implies a “push” from the fields, and into industry and the cities. Desperate, and unable to demand high wages, these cheaper workers should have stimulated industry’s growth.

The alternative, however, is that there was nothing very special or innovative about English agriculture, and that instead there was an even larger increase in the demand for workers in industry and services. The thesis implies a “pull” into industry and the cities, causing people to abandon agriculture for more profitable pursuits, and thereby making England’s agriculture de facto more productive — something that may or may not have actually been accompanied by any changes to agricultural technology, depending on how much slack there was in how the labourers or land had been employed.

The push thesis implies agricultural productivity was an original cause of England’s structural transformation; the pull thesis that it was a result. The evidence, I think, is in favour of a pull — specifically one caused by the dramatic growth of London’s trade.

Even though the population eventually recovered from the massive impact of the Black Death, not all of the land that was under plough was returned to active farming and a much greater diversity of uses for rural land emerged, including more pastures for grazing livestock, and small cash crops to be sold into the cities (especially into London).

With the dramatic growth of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the more intensive methods came to be in much higher demand. Indeed, the extraordinary pull of the city’s growth resulted in English agriculture becoming increasingly specialised. Not only were there millions of acres of pasture still left that could be returned to the plough, but despite the relative fall in the prices of livestock, some areas actually became even more devoted to pasture. Many of the villages that had been abandoned after the Black Death were, even by the 1870s, over half a millennium later, still not being farmed. With wealthy Londoners demanding more varied diets, with meat and dairy, the various regions of England discovered their comparative advantages rather than all shifting to grain. There was thus extra room for agriculture to become more productive simply by devoting the best land for pasture to pasture, and the best soils for arable to arable, then trading the produce with one another, rather than have each area try to be self-sufficient. It’s something we also see in the decline of grains like rye, especially near London, to be replaced by wheat — the switching of a crop best-suited to local subsistence, to one that could be sold elsewhere and in bulk for cash.

In general, the south and east of England became increasingly arable, while the north-west concentrated on pasture. Yet there were also exceptions to be made for London’s particular wants. Thus, county Durham converted more land to arable to feed the miners of Newcastle coal, used to heat London’s homes; and the county of Middlesex, now largely disappeared under London’s own expansion, specialised in pasture for horses, rather than feeding people, so as to feed the city’s main sources of transportation. As the writer Daniel Defoe put it in the 1720s, “this whole Kingdom, as well the people, as the land, and even the sea, in every part of it, are employed to furnish something, and I may add, the best of everything, to supply the city of London with provisions.”

May 9, 2021

Why Siege Towers are Wrong – History and Evolution

Invicta

Published 1 Feb 2021The depiction of siege towers as massed, glorified troop elevators in most modern media is completely a-historic. In this video let’s reveal the true history of the Siege Tower.

Check out The Great Courses Plus to learn about daily life in the past: http://ow.ly/DWyz30rsjSX

In this video we explore the history of siege warfare and in particular the siege tower. This begins with our earliest civilizations in the Fertile Crescent. It is here in ancient Mesopotamia that people like the Assyrians began to experiment with new siege technology such as the siege tower. We look specifically at the best example of Assyrian Warfare and the Assyrian army with the Siege of Lachish. From here, siege technology would spread to nearby Egypt and across the Mediterranean. The Greeks picked it up and helped push the technology forward with great application in the campaigns of Alexander the Great. The Roman Army then adopted the Siege Tower and worked to perfect its application. We then finally turn to the use of the Siege Tower in the middle ages. Along the way we cover lots of specific examples like The Siege of Alesia, The Siege of Jerusalem, the Siege of Masada and much more.

#History

#Documentary

May 2, 2021

April 30, 2021

QotD: The battle of Bannockburn

The Scots were now under the leadership of the Bruce (not to be confused with the Wallace), who, doubtful whether he had slain the Red Comyn or not, armed himself with an enormous spider and marched against the English, determined if possible to win back the Great Scone by beating the English three times running.

The fact that the English were defeated has so confused Historians that many false theories are prevalent about the Bannockburn Campaign. What actually happened is quite clear from the sketch map shown above. The causes of the English defeat were all unfair and were:

- The Pits. Every time the Wallace saw some English Knights charging at him he quickly dug one of these unnatural hazards into which the English Knights, who had been taught to ride straight, galloped with flying colours.

- Superior numbers of the English (four to one). Accustomed to fight against heavy odds the English were uneasy, and when the Scots were unexpectedly reinforced by a large body of butlers with camp stools the English soldiers mistook them for a fresh army of Englishmen and retreated in disgust.

- Foul riding by Scottish Knights. This was typified even before the battle during an exhibition combat between the Brace and the English Champion, Baron Henry le Bohunk, when Brace, mounted on a Shetland pony, galloped underneath the Baron and, coming up unexpectedly on the blind side, struck him a foul blow behind and maced him up for life.

W.C. Sellar & R.J. Yeatman, 1066 And All That, 1930.

April 3, 2021

March 29, 2021

The Bayeux Tapestry – all of it, from start to finish

Lindybeige

Published 18 Oct 2017A complete guide to the story as depicted on the famous Bayeux Tapestry. There is a lot more to it than just the Battle of Hastings.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Other than The Adventures of Stoke Mandeville, this is the longest editing job I have ever done. It took eleven very long days of work to put this together from the opportunist footage I snatched when changing trains near the museum where it is on display. The shoot was not without its problems, one of which was the fact that because the tapestry is behind glass, and the museum has many illuminated displays, the reflections in the glass were a bane, and I didn’t manage to get rid of them all. Another was that my stills camera refused to work after taking a small number of pictures. It had always worked fine before, and has always worked fine since. It wasn’t the battery and it wasn’t the SD card. It was a mystery.

For the curious, the edit involved seventeen tracks on the timeline, and has twenty-two animated scenes. Unfortunately, the main animation software I was using could not handle full HD images, and so there is a slight loss of picture quality during most of the animated scenes. You will notice that the close-ups have a better picture quality than the wide shots. This is because they were taken with the camera pushed up against the glass, which improved focussing, and got rid of almost all of the haze and reflections caused by the glass.

It is important to understand that this ‘tapestry’ is a piece of propaganda, and does not tell an accurate version of events. The story I tell here is the one depicted, not what actually happened.

I have enough material for more videos on the tapestry, but am in no great hurry to spend many more days editing this difficult footage. Trying to match the writing and speaking of narration to panning camerawork that had no notion when shot of what might need to be said about some passing scene, was a nightmare, and many editing compromises had to be made, with some scenes skipped past quickly, and others drawn out.

Clarification on the nudity: I said that the figure under the mysterious Cleric and woman was the the only figure displaying genitals on the tapestry. This was misleading. Several animals clearly are pictured with genitals, and on the tapestry in Bayeux today it looks as though a couple of other human figures have genitals. Some of these may have been added later, and these are not being ‘displayed’ as the displaying figure is clearly doing, but look more incidental.

I describe the tall figure emerging from the building with a lance and pennant, being brought his horse, as “William”. It occurred to me after making the video that all the sources I consulted describe this figure as William, but the text does not name him as William, so possibly he is just a Norman knight, representing any and all of the knights setting out for the battle, and that this figure is meant to be “William” could be a modern tradition that has become accepted fact just by repetition.

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

March 8, 2021

The Rise of Artillery in European Siege Warfare

SandRhoman History

Published 7 Mar 2021Get 25% off an annual membership of CuriosityStream using code

sandrhoman: https://curiositystream.com/sandrhomanAt the end of the Middle Ages, a new weapon system changed the face of 15th century European siege warfare: artillery made its appearance. It had an impressive impact best shown by one peculiar fact. Imagine a walled fortress in the 14th century. It could easily deter attackers for several months. But in the early 15th up to the early 16th century, after artillery had fully developed, the same walls fell within days. As a result, engineers had to construct much more elaborate defensive structures. By the early to mid 16th century a fortress could again withstand a siege with heavy artillery for several months. This is how modern historiography explains the rise of artillery.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sandrhomanhis…

Bibliography:

Ayton, A., / Price, J. L., (Hrsg.), The Medieval Military Revolution. State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, 199J.

Black, A Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society 1550–1800, 1991.

Devries, K., Medieval Military Technology, 1994.

Ortenburg, G., Waffe und Waffengebrauch im Zeitalter der Landsknechte (Heerwesen der Neuzeit, Abt. 1, Bd. 1) Koblenz 1984.

Rogers, C. J., “Military Revolutions of the Hundred Years War”, in: Rogers et al. The Military Revolution Debate. Reading on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe, 1995, p. 13-35.

Schmidtchen, V., Kriegswesen im Spätmittelalter, 1990.

March 6, 2021

March 2, 2021

The Evolution of Shock Cavalry – From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

Invicta

Published 1 Mar 2021Learn about the evolution of shock cavalry from antiquity before the use of saddles and stirrups! Check out The Great Courses Plus to learn about shock cavalry in the campaigns of Alexander the Great: http://ow.ly/osex30rvhjf

In this history documentary we explore the topic of ancient cavalry. The basic idea is that these units often get depicted in media as performing glorious massed charges headlong into the enemy ranks as seen in such scenes as the Charge of the Rohirrim from the Battle of Pelenor Fields. In reality this would have been a very dangerous situation for cavalrymen even under the best circumstances. But to make matters worse, riders from antiquity fought without the use of either saddles or stirrups. So how on earth did they manage to dominate the battlefield with these handicaps. Let’s find out.

We begin by covering the history of cavalry with the first domestication of the horse and its introduction to warfare first as member of the baggage train and soon after as a part of chariot crews rather than as actual mounted forces. This was in large part due to the lack of riding experience and technology on behalf of the rider. Soon after the Bronze Age Collapse however cavalry began to rise to prominence across the armies of the Mediterranean. We speak about the various forms of equine practices which ranged from riding bareback into combat as with the Numidian Cavalry to the use of simple bridles and cloth seats as with Greek Cavalry and Persian Cavalry.

We then cover the techniques used by these cavalrymen to mount, ride, and fight. As a part of this discussion, we rely heavily on Xenophon’s Manual on Horsemanship which provides excellent first hand details from the period. We also show how these techniques were successfully used by shock cavalry of antiquity such as the Macedonian Companion Cavalry, the Saka Steppe Lancers, and the Persian Cataphracts to great effect even without the use of saddles and stirrups.

Finally we do pose the question of why they didn’t use the saddle and stirrup given its seemingly obvious advantages. To answer this question we look at the history of its development from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages.

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

On Horsemanship, by Xenophon

Adrian Goldsworthy, The Complete Roman Army

Adrian Goldsworthy, Roman Warfare

J.C. Coulston, Cavalry Equipment of the Roman Army in the First Century A.D.

George T. Dennis, Maurice’s Strategikon, p. 38.

Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Civili

Russel H. Beaty, Saddles#History

#Documentary

#ShockCavalry

From the comments:

Invicta

13 hours ago

I was inspired by comments on our latest Units of History episode covering the Companion Cavalry which asked about how shock tactics worked in an age before the stirrup and saddle. I went down the rabbit hole finding answers and present to you my findings in this video! One awesome source we used was the Manual on Horsemanship by Xenophon which you can read for yourself here: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1176/1176-h/1176-h.htm

February 22, 2021

The “Infantry Revolution” of the Late Middle Ages

SandRhoman History

Published 21 Feb 2021CuriosityStream link: https://curiositystream.com/sandrhoman

The “Infantry Revolution” of the late Middle Ages is kind of a hot topic among armchair historians and academics alike. This is how the argument goes: In the late Middle Ages, infantry grew in importance to the detriment of heavy cavalry; by then battles were increasingly won with pikes, longbows and arquebuses instead of mounted knights with lances, the argument continues, and as a result of that, the socio-political make-up and development of European polities changed lastingly. So, this Infantry Revolution supposedly had an incredible impact on European state building processes AND, the argument finally concludes, it laid the foundation to Europe’s conquest and colonization of many parts of the world. However, in public spaces such as YouTube this whole debate is more discussed in regards to tactics and fighting techniques than economics and politics. Consequently, much of the public discussion is about how and if the importance of knights changed after the High Middle Ages. Likewise, topics such as the efficacy of the English longbow or the impact of pikes in the late Middle Ages are frequently the subject of discussions. All of that is controversial to say the least but it gets worse: these changes must be viewed in the broader military changes such as the rise of gunpowder artillery between 1420 and 1530 — called an artillery revolution — the decline of sieges between the 1420s and the 1530s which, among many things, led to the resurgence of heavy cavalry in the later late Middle Ages. Lastly, all of these revolutions belong to a notion called “military revolution”. This video is not intended to argue one side or the other of the “infantry revolution” but to provide a broad overview over both the debate and the military changes during the 14th and 15th centuries. It explains how contemporary historiography quarrels over the infantry revolution.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sandrhomanhis…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SandrhomanBibliog…

Bibliography:

Bane, M., English Longbow Testing against various armor circa 1400, 2006.

Ayton, A., / Price, J. L., (Hrsg.), The Medieval Military Revolution. State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, 199J.

Black, A Military Revolution? Military Change and European Society 1550–1800, 1991.

Devries, K., Medieval Military Technology, 1994.

Dierk, W., s.v. “Heeresreform”, in: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit

Ortenburg, G., “Waffe und Waffengebrauch im Zeitalter der Landsknechte” (Heerwesen der Neuzeit, Abt. 1, Bd. 1) Koblenz 1984.

Magier, Mariusz; Nowak, Adrian; et al., “Numerical Analysis of English Bows used in Battle of Crécy”. Problemy Techniki Uzbrojenia. 142 (2), 2017, 69–85.

Meumann, M., s.v. “Military Revolution”, in: Enzyklopädie der Neuzeit.

Parker G., “The ‘Military Revolution’, 1560–1660 – a Myth?”, in: Journal of Modern History 48.2, 1976, 196–214

Parker, G., Die militärische Revolution. Die Kriegskunst und der Aufstieg des Westens 1500–1800, 1990 (Engl. 1988)

Roberts, M.: “The military revolution, 1560–1660”. In: Clifford J. Rogers: The military revolution debate. Readings on the military transformation of early modern Europe. Westview Press, Boulder, Colo. 1995, S. 13–35.

Rogers, C.J. / Tallet F. (editors), European Warfare, 1350–1750, 2010.

Rogers, C.J., The Efficacy of the English Longbow, 1998.

Schmidtchen, Volker, Kriegswesen im späten Mittelalter. Technik, Taktik, Theorie, Weinheim 1990.

Soar, H., Gibbs, J., Jury, C., Stretton, M., Secrets of the English War Bow. Westholme, 2010, pp. 127–151.

February 8, 2021

Why Everybody Disagrees on the Efficacy of the English Longbow – A Video Essay

SandRhoman History

Published 7 Feb 2021Everybody quarrels over the efficacy of the English longbow. Many historians, reenactors and history enthusiasts alike hold the view that arrows piercing armor is a myth. Some base this view on testing as was done for example by Tod from Tod’s workshop. Together with his team, he provided an invaluable data point for this debate. Others, such as traditionalist historians are often open to the possibility of arrows piercing armor, even though they are aware of actual testing of the longbow. In general, the efficacy of a weapon is much more complicated than its mere armor penetration value. So, in this video we’d like to shed light on the whole debate and explain why it is so hard to find common ground on this issue. This is why everybody disagrees on the efficacy of the English longbow.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sandrhomanhis…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Sandrhoman

Tod’s Video: ARROWS vs ARMOUR – Medieval Myth Busting https://youtu.be/DBxdTkddHaE

Tod’s playlist: MEDIEVAL MYTH BUSTING https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLI…

Bibliography:

Rogers, C.J., The Efficacy of the English Longbow, 1998.

Devries, K., Medieval Military Technology, 1994.

Bane, M., “English Longbow Testing against various armor circa 1400”, 2006.

Soar, H., Gibbs, J., Jury, C., Stretton, M., Secrets of the English War Bow. Westholme, 2010, pp. 127–151.

Magier, Mariusz; Nowak, Adrian; et al., “Numerical Analysis of English Bows used in Battle of Crécy”. Problemy Techniki Uzbrojenia. 142 (2), 2017, 69–85.

January 22, 2021

QotD: The enclosure movement, in historical fact and in Marxist imagining

Consider, for example, that the tenfold increase [in the population of London] was in the period before the expropriative parliamentary enclosures of Marxist legend, when state fiat was used to deny smaller farmers their ancient, customary rights to use the land near their villages. While the very first of these enclosure acts appeared as early as 1604, parliamentary enclosure only really got going from the mid-eighteenth century. Instead, for the period in question, enclosure happened in a piecemeal way, with the open fields gradually dissolving as farmers exchanged or sold their tiny strips of land, over time amalgamating them into larger, privately controlled plots. With ownership concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, it became relatively easy to gain the unanimity needed to suspend common rights. The process played out in myriad ways all over the country, sometimes with amicable agreement and voluntary exchange, sometimes with ruthless monopolising of the land, with the already-large owners systematically buying out their neighbours. In some cases it involved the consolidation of existing arable land, in others it meant the conversion of forest, heath, marsh, or fen — the traditional “wastes”, to which the poorer villagers might have had various customary rights to gather firewood for fuel, or to graze their cattle, or to hunt for small game — into land that could be used for farming or pasture.

How this process played out all depended on extremely specific, local conditions. But on the whole it was slow — piecemeal enclosure had been happening to varying degrees since at least the fourteenth century. It’s hard to see how such a sporadic and piecemeal process could have led to such consistently and increasingly massive numbers flocking specifically to London. Indeed, the fact that they singled out London as their target suggests that this narrative might have it back-to-front. Some economic historians argue that it was the prospect of higher wages in the ever-growing metropolis that induced farmers to leave the countryside in the first place, selling up or abandoning their plots to those they left behind. Rather than enclosure pushing peasants off the land and into the city, London’s specific pull may instead have thus created the vacuum that allowed the remaining farmers to bring about enclosure. Otherwise, why didn’t the peasants simply flock to any old urban centre? The second-tier cities like Norwich or Bristol or Exeter or Coventry or York would all have been far less dangerous.

Anton Howes, “London the Great”, Age of Invention, 2020-10-20.

December 10, 2020

Making a Morning Star (Flail) for my Nephew

Rex Krueger

Published 9 Dec 2020Forged in Wood comes back hot with this Morning Star build!

More video and exclusive content: http://www.patreon.com/rexkrueger

Get the FREE measured drawing of the London Pattern Handle: https://www.rexkrueger.com/store

More woodshop weaponry builds below!

* Gun-Stock War Club: https://youtu.be/mFvBIJLciuc

* Viking Shield: https://youtu.be/AShF_5JOM2c

* Spiked Mace: https://youtu.be/Ig4H-ozMHNISign up for Fabrication First, my FREE newsletter: http://eepurl.com/gRhEVT

Wood Work for Humans Tool List (affiliate):

*Cutting*

Gyokucho Ryoba Saw: https://amzn.to/2Z5Wmda

Dewalt Panel Saw: https://amzn.to/2HJqGmO

Suizan Dozuki Handsaw: https://amzn.to/3abRyXB

(Winner of the affordable dovetail-saw shootout.)

Spear and Jackson Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/2zykhs6

(Needs tune-up to work well.)

Crown Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/3l89Dut

(Works out of the box)

Carving Knife: https://amzn.to/2DkbsnM

Narex True Imperial Chisels: https://amzn.to/2EX4xls

(My favorite affordable new chisels.)

Blue-Handled Marples Chisels: https://amzn.to/2tVJARY

(I use these to make the DIY specialty planes, but I also like them for general work.)*Sharpening*

Honing Guide: https://amzn.to/2TaJEZM

Norton Coarse/Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/36seh2m

Natural Arkansas Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/3irDQmq

Green buffing compound: https://amzn.to/2XuUBE2*Marking and Measuring*

Stockman Knife: https://amzn.to/2Pp4bWP

(For marking and the built-in awl).

Speed Square: https://amzn.to/3gSi6jK

Stanley Marking Knife: https://amzn.to/2Ewrxo3

(Excellent, inexpensive marking knife.)

Blue Kreg measuring jig: https://amzn.to/2QTnKYd

Round-head Protractor: https://amzn.to/37fJ6oz*Drilling*

Forstner Bits: https://amzn.to/3jpBgPl

Spade Bits: https://amzn.to/2U5kvML*Work-Holding*

Orange F Clamps: https://amzn.to/2u3tp4X

Screw Clamp: https://amzn.to/3gCa5i8Get my woodturning book: http://www.rexkrueger.com/book

Follow me on Instagram: @rexkrueger

November 15, 2020

London’s wool and cloth trade fuelled massive growth in the city’s population after 1550

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the rise and fall of the late Medieval wool trade and its rebirth largely thanks to an influx of Dutch and Flemish clothmakers fleeing the wars in the Low Countries after 1550:

The Coat of Arms of The Worshipful Company of Woolmen — On a red background, a silver woolpack, with the addition of a crest on a wreath of red and silver bearing two gold flaxed distaffs crossed like a saltire and the wheel of a gold spinning wheel.

The Worshipful Company of Woolmen is one of the Livery Companies in the City of London. It is known to have existed in 1180, making it one of the older Livery Companies of the City. It was officially incorporated in 1522. The Company’s original members were concerned with the winding and selling of wool; presently, a connection is retained by the Company’s support of the wool industry. However, the Company is now primarily a charitable institution.

The Company ranks forty-third in the order of precedence of the Livery Companies. Its motto is Lana Spes Nostra, Latin for Wool Is Our Hope.

Wikipedia.

… it was one thing to be able to reach these new southern markets, and another thing to have something to sell in them. For the shift in the markets for wool cloth exports also required major changes in the kinds of cloth produced. In this regard, London may well have been a direct beneficiary of the 1560s-80s troubles in the Low Countries that had caused Antwerp’s fall, because thousands of skilled Flemish and Dutch clothmakers fled to England. In particular, these refugees brought with them techniques for making much lighter cloths than those generally produced by the English — the so-called “new draperies”, which could find a ready market in the much warmer Mediterranean climes than the traditional, heavy woollen broadcloths.

The introduction of the new draperies was no mere change in style, however. They were almost a completely different kind of product, involving different processes and raw materials. The traditional broadcloths were “woollens”. That is, they were made from especially fine, short, and curly wool fibres — the type that English sheep were especially famous for growing — which were then heavily greased in butter or oil in preparation for carding, whereby the fibres were straightened out and any knots removed (because of all the oil, in the Low Countries the cloths were known as the wet, or greased draperies). The oily, carded wool was then spun into yarn, and typically woven into a broad cloth about four metres wide and over thirty metres long. But it was still far from ready. The cloth had to be put in a large vat of warm water, along with some urine and a particular kind of clay, and was then trodden by foot for a few days, or else repeatedly compacted by water-powered machinery. This process, known as fulling, scoured the cloth of all the grease and shrunk it, compacting the fibres so that they began to interlock and enmesh. Any sign of the cloth being woven thus disappeared, leaving a strong, heavy, and felt-like material that was, as one textile historian puts it, “virtually indestructible”. To finish, it was then stretched with hooks on a frame, to remove any wrinkles and even it out, and then pricked with teasels — napped — to raise any loose fibres, which were then shorn off to leave it with a soft, smooth, sometimes almost silky texture. Woollens may have been made of wool, but they were no woolly jumpers. They were the sort of cloth you might use today to make a thick, heavy and luxuriant jacket, which would last for generations.

Yet this was not the sort of cloth that would sell in the much warmer south. The new draperies, introduced to England by the Flemish and Dutch clothworkers in the mid-sixteenth century, used much lower-quality, coarser, and longer wool. Later generally classed as “worsteds”, after the village of Worstead in Norfolk, they were known in the Low Countries as the dry, or light draperies. They needed no oil, and the long fibres could be combed rather than carded. Nor did they need any fulling, tentering, napping, or shearing. Once woven, the cloth was already strong enough that it could immediately be used. The end product was coarser, and much more prone to wear and tear, but it was also much lighter — just a quarter the weight of a high-quality woollen. And the fact that the weave was still visible provided an avenue for design, with beautiful diamond, lozenge, and other kinds of patterns. The new draperies, which included worsteds and various kinds of slightly heavier worsted-woollen hybrids, as well as mixes with other kinds of fibre like silk, linen, Syrian cotton, or goat hair, thus came in a dazzling number of varieties and names: from tammies or stammets, to rasses, bays, says, stuffs, grograms, hounscots, serges, mockadoes, camlets, buffins, shalloons, sagathies, frisadoes, and bombazines. To escape the charge that the new draperies were too flimsy and would not last, some varieties were even marketed as durances, or perpetuanas.

Curiously, however, while the shift from woollens to worsted saved on the costs of oiling, fulling, and finishing, it was significantly more labour-intensive when it came to spinning — even resulting in a sort of technological reversion. Given the lack of fulling, the strength of the thread mattered a lot more for the cloth’s durability, and the yarn had to be much finer if the cloth was to be light. The spinning thus had to be done with much greater care, which made it slower. Spinners typically gave up using spinning wheels, instead reverting to the old method of using a rock and distaff — a technique that has been used since time immemorial. Albeit slower, the rock and distaff gave them more control over the consistency and strength of the ever-thinner yarn. For the old, woollen drapery, processing a pack of wool into cloth in a week would employ an estimated 35 spinners. For the new, lighter worsted drapery it would take 250. As spinning was almost exclusively done by women, the new draperies provided a massive new source of income for households, as well as allowing many spinsters or widows to support themselves on their own. Indeed, an estimated 75% of all women over the age of 14 might have been employed in spinning to produce the amounts of cloth that England exported and consumed. Some historians even speculate that by allowing women to support themselves without marrying, it may have lowered the national fertility rate.

This spinning, of course, was not done in London. It was largely concentrated in Norfolk, Devon, and the West Riding of Yorkshire. But the new draperies provided employment of another, indirect kind. As a product that was saleable in warmer climes it could be exchanged for direct imports of all sorts of different luxuries, from Moroccan sugar, to Greek currants, American tobacco (imported via Spain), and Asian silks and spices (initially largely imported via the eastern Mediterranean). The English merchants who worked these luxury import trades were overwhelmingly based in London, and had often funded the voyages of exploration and embassies to establish the trades in the first place, putting them in a position to obtain monopoly privileges from the Crown so that they could restrict domestic competition and protect their profits. Unsurprisingly, as they imported everything to London, it also made sense for them to export the new draperies from London too.

Thus, despite losing the concentrating influence of nearby Antwerp, London came to be the principal beneficiary of England’s new and growing import trades, allowing it to grow still further. The city began to carve out a role for itself as Europe’s entrepôt, replacing Antwerp, and competing with Amsterdam, as the place in which all the world’s rarities could be bought (and from which they could increasingly be re-exported). Indeed, English merchants were apparently happy to sell wool cloth at below cost-price in markets like Spain or Turkey — anything to buy the luxury wares that they could monopolise back home.