Along with this, you see a growing respect for numbers [in the 15th century]. Medieval statistics are Rachel Maddowesque — whatever they felt they needed to say to get the job done. “We were opposed by fifty thousand Saracens” could mean anything from “bad guys as far as the eye could see” to “we were slightly outnumbered” to “it just wasn’t our day, so we ran”. 15th century numbers aren’t what you’d call real factually accurate, but they’re getting there. 16th century numbers are usually in the ballpark, and you can usually cross-check them in various ways. There’s just a hell of a lot more paper in general, and that paper is a lot more scrupulous.

All of this, I suggest, is because people increasingly thought factual accuracy was important. And that only comes with the increasing sense of linear time. The chronicles of the first two or three Crusades, for instance, are filled with wild exaggerations and impossible claims … but they’re not lies. They just serve a different purpose. They’re called “histories”, but that’s a misleading translation (of the word historia, I’ll admit). What they really are is much closer to exempla — saints’ lives, that kind of thing. Their point isn’t “This and that actually happened”; it’s more like “Let us all praise God, for the wondrous things he allowed us to do!”

Gesta Francorum means “deeds of the French”, but in the sense of “The wonders done in God’s name,” not “a list of battles and their outcomes”.

Severian, “The Ghosts (II)”, Founding Questions, 2022-05-18.

March 3, 2026

QotD: The rise of archives-based history in the late Middle Ages

March 2, 2026

QotD: King Stephen and “the anarchy”

Picture the scene: it is a dark night in late November. A cross-channel ferry is about to set sail for England. A posh young man, a boy really, boards the ship with his posh mates. They’re not short of money and before long they’re seriously drunk. Some of the other passengers disembark. They hadn’t signed-up for a booze cruise — and, what’s more, the young men are carrying knives. Well, I say “knives” — what I actually mean is swords.

At this point, I ought to mention that the year is 1120; the young man is William Adelin, heir to the throne of England; and the “ferry” is the infamous White Ship.

Anyway, back to the story: the wine keeps flowing and, before long, the crew are drunk too. Not far out of port, the ship hits a submerged rock and rapidly sinks.

In all, hundreds are drowned — and yet that is just the start of the tragedy.

William’s father, King Henry I, had gone to great lengths to proclaim an heir. As the son of William the Conqueror, he knew just how messy succession could get. He had himself inherited the throne from his brother, William Rufus. This second William had died of a chest complaint — specifically, an arrow in the lungs (the result of a hunting “accident”). Henry was determined that his son would inherit the throne without mishap — and so carefully prepared the ground for a smooth transfer. Indeed, the name “Adelin” signified that the third William was the heir apparent.

The sinking of the White Ship left Henry with one remaining legitimate heir, his daughter Matilda. She was a formidable character, also known as Empress Maud (by virtue of her first marriage to the Holy Roman Emperor). She was, nevertheless, a woman — a big problem in an age when monarchs were expected to lead their men in battle. When Henry died in 1135, Maud’s cousin — Stephen of Blois — seized the throne. This was widely welcomed by the English nobility, but Maud wasn’t giving up easily, and she had powerful allies. Her second husband was Geoffrey, Count of Anjou; her illegitimate half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was a wealthy baron; and her uncle was King David I of Scotland.

Stephen was assailed on all sides — by Geoffrey in Normandy, by Robert in England, by invading Scots and rebellious Welshmen. The civil war (if that’s what you can call this multi-sided free-for-all) dragged on for almost 20 years. There weren’t many set-piece battles, but there was lots of looting and pillaging in which countless nameless peasants perished.

In the end it was the death of another heir — Stephen’s son, Eustace — that opened the way to peace. The war-weary king agreed that Maud’s son (the future Henry II) would succeed him. And thus “The Anarchy” came to end: two decades of pointless devastation — and all because some young fool got pissed on a boat.

Peter Franklin, “Why Boris needs an heir apparent”, UnHerd, 2020-08-17.

February 22, 2026

QotD: The shift from “motte-and-bailey” construction to stone castles

As we move to stone construction and especially full stone construction (which we’ll define as the point when at least one complete curtain wall – don’t worry, we’ll define that in a second – is in stone) in the 12th century, we’re beginning to contemplate a different kind of defense. The wooden motte and bailey, as we’ve seen, mostly served to resist both raids and “hasty” assaults, thus forcing less coordinated or numerous attackers to set in to starve the castle out or go home. But stone walls are a much larger investment in time and resources; they also require a fair bit more careful design in order to be structurally sound. For all of that expense, the builder wants quite a bit of a security, and in the design of stone castles it is hard not to notice increasing attention towards resisting a deliberate assault; stone castles of the 12th century and beyond are increasingly being designed to stand up to the best that the “small army” playbook can throw at them. Of course it is no accident that this is coming at the same time that medieval European population and wealth is beginning to increase more rapidly, leaving political authorities (read: the high nobility) with both the resources for impressive new castles (although generally the number of castles falls during this period – fewer, stronger castles) and at the same time with more resources to invest in the expertise of siegecraft (meaning that an attacker is more likely to have fancy tools like towers, catapults and better coordination to use them).

To talk about how these designs work, we need to clear some terminology. The (typically thin) wall that runs the circuit of the castle and encloses the bailey is called a “curtain wall“. In stone castles, there may be multiple curtain walls, arranged concentrically (a design that seems to emerge in the Near East and makes its way to Europe in the 13th century via the crusades); the outermost complete circuit (the primary wall, as it were) is called the enceinte. Increasingly, the keep in stone castles is moved into the bailey (that is, it sits at the center of the castle rather than off to one side), although of course stone versions of motte and bailey designs exist. In some castle design systems, with stone the keep itself drops away, since the stone walls and towers often provided themselves enough space to house the necessary peacetime functions; in Germany there often was no keep (that is, no core structure that contained the core of the fortified house), but there often was a bergfriede, a smaller but still tall “fighting tower” to serve the tactical role of the keep (an elevated, core position of last-resort in a defense-in-depth arrangement) without the peacetime role.

While the wooden palisade curtain walls of earlier motte and bailey castles often lacked many defensive features (though sometimes you’d have towers and gatehouses to provide fighting positions around the gates), stone castles tend to have lots of projecting towers which stick out from the curtain wall. The value of projecting towers is that soldiers up on those towers have clear lines of fire running down the walls, allowing them to target enemies at the base of the curtain wall (the term for this sort of fire is “enfilade” fire – when you are being hit in the side). Clearly what is being envisaged here is the ability to engage enemies doing things like undermining the base of walls or setting up ladders or other scaling devices.

The curtain walls themselves also become fighting positions. Whether on a tower or on the wall itself, the term for the fighting position at the top is a “battlement”. Battlements often have a jagged “tooth” pattern of gaps to provide firing positions; the term for the overall system is crenellation; the areas which have stone are merlons, while the gaps to fire through are crenals. The walkway behind both atop the wall is the chemin de ronde, allure or “wall-walk”. One problem with using the walls themselves as fighting positions is that it is very hard to engage enemies directly beneath the wall or along it without leaning out beyond the protection of the wall and exposing yourself to enemy fire. The older solution to this were wooden, shed-like projections from the wall called “hoarding”; these were temporary, built when a siege was expected. During the crusades, European armies encountered Near Eastern fortification design which instead used stone overhangs (with the merlons on the outside) with gaps through which one might fire (or just drop things) directly down at the base of the wall; these are called machicolations and were swiftly adopted to replace hoardings, since machicolations were safer from both literal fire (wood burns, stone does not) and catapult fire, and also permanent. All of this work on the walls and the towers is designed to allow a small number of defenders to exchange fire effectively with a large number of attackers, and in so doing to keep those attackers from being able to “set up shop” beneath the walls.

[I]t is worth noting something about the amount of fire being developed by these projecting towers: the goal is to prevent the enemy operating safely at the wall’s base, not to prohibit approaches to the wall. These defenses simply aren’t designed to support that much fire, which makes sense: castle garrisons were generally quite small, often dozens or a few hundred men. While Hollywood loves sieges where all of the walls of the castle are lined with soldiers multiple ranks deep, more often the problem for the defender was having enough soldiers just to watch the whole perimeter around the clock (recall the example at Antioch: Bohemond only needs one traitor to access Antioch because one of its defensive towers was regularly defended by only one guy at night). It is actually not hard to see that merely by looking at the battlements: notice in the images here so far often how spaced out the merlons of the crenellation are. The idea here isn’t maximizing fire for a given length of wall but protecting a relatively small number of combatants on the wall. As we’ll see, that is a significant design choice: castle design assumes the enemy will reach the walls and aims to prevent escalade once they are there; later in this series we’ll see defenses designed to prohibit effective approach itself.

As with the simpler motte and bailey, stone castles often employ a system of defense in depth to raise the cost of an attack. At minimum, generally, that system consists of a moat (either wet or dry), the main curtain walls (with their towers and gatehouses) and then a central keep. Larger castles, especially in the 13th century and beyond, adopting cues from castle design in the Levant (via the crusades) employed multiple concentric rings of walls. Generally these were set up so that the central ring was taller, either by dint of terrain (as with a castle set on a hill) or by building taller walls, than the outer ring. The idea here seems not to be stacking fire on approaching enemies, but ensuring that the inner ring could dominate the outer ring if the latter fell to attackers; defenders could fire down on attackers who would lack cover (since the merlons of the outer ring would face the other way). As an aside, the concern to be firing down is less about the energy imparted by a falling arrow (though this is more meaningful with javelins or thrown rocks) and more about a firing position that denies enemies cover by shooting down at them (think about attackers, for instance, crossing a dry moat – if your wall is the right height and the edges of the moat are carefully angled, you can set up a situation where the ditch never actually offers the attackers any usable cover, but you need to be high up to do it!).

Speaking of the moat, this is a common defensive element (essentially just a big ditch!) which often gets left out of pop culture depictions of castles and siege warfare, but it accomplishes so many things at such a low cost premium. Even assuming the moat is “dry”! For attackers on foot (say, with ladders) looking to approach the wall, the moat is an obstacle that slows them down without potentially providing any additional cover (it is also likely to disorder an attack). For sappers (attackers looking to tunnel under the walls and then collapse the tunnel to generate a breach), the depth of the ditch forces them to dig deeper, which in turn raises the demands in both labor and engineering to dig their tunnel. For any attack with siege engines (towers, rams, or covered protective housings made so that the wall can be approached safely), the moat is an obstruction that has to be filled in before those engines can move forward – a task which in turn broadcasts the intended route well in advance, giving the defenders a lot of time to prepare.

Well-built stone castles of this sort were stunningly resistant to assault, even with relatively small garrisons (dozens or a few hundred, not thousands). That said, building them was very expensive; maintaining them wasn’t cheap either. For both castles and fortified cities, one ubiquitous element in warfare of the period (and in the ancient period too, by the by) was the rush when war was in the offing to repair castle and town walls, dig out the moat and to clear buildings that during peace had been built int he firing lines of the castle or city walls.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part III: Castling”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-10.

February 19, 2026

QotD: The Donation of Constantine

Y’all know I love the 15th century. Not “the Renaissance”, although “the Renaissance” — insofar as that’s a useful concept of historical analysis, which is not very — was in full swing in Italy by 1400, and soon enough north of the Alps, too. The professional periodization and terminology can be confusing here — the “Northern Renaissance” can refer to different things, sometimes a hundred or more years apart, depending on whether you’re talking about visual arts or poetry or what have you. So I prefer to confine the term “Renaissance” to Italy. Unless I’m talking specifically and exclusively about Italy, I’ll refer to the period as “the 15th century”.

I love it because it’s clearly a watershed moment in human thought. I don’t mean the rediscovery of the classical past; I mean the shift between a more cyclical orientation towards life, versus an orientation around linear time. Time as the regular procession of the seasons, vs. time as a stream or river.

Some examples will help. The 15th century saw not just the creation of archives-based history, but the techniques in various fields that make archival work possible. For instance, the Donation of Constantine was definitively proved to be a forgery in the 15th century, on the basis of philological evidence. Before that point, the people using the Donation – both ways — wouldn’t have cared too much if they knew it was a fake. Not because they were opportunists (although they were), but because “factual accuracy”, to use one of my favorite of the Media’s many Freudian slips, just didn’t matter much back then.

When they said “the Donation of Constantine” they meant “hallowed by tradition”, and if you’d proved to them that the Donation was fake, they’d just keep on keepin’ on — ok, then, “hallowed by tradition” it is, everyone update your style books accordingly.

Severian, “The Ghosts (II)”, Founding Questions, 2022-05-18.

February 3, 2026

The Killer Pigs of the Middle Ages

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 5 Aug 2025Sliced roasted pork loin with jus

City/Region: England

Time Period: 1390Pigs were an important source of food in the Middle Ages. They didn’t take up a lot of space, had lots of babies, and ate pretty much anything, so despite their smell and bouts of violence (sometimes ending in murder), they were commonly found throughout Europe.

This English recipe, which uses black pepper, coriander seed, caraway seed, and wine, all expensive ingredients that had to come from far away, wouldn’t have been for the common folk. Today, these ingredients are readily found at the grocery store, and this is a delicious roast that is perfect for those just getting into medieval cooking. As with a lot of historical recipes, there are no quantities given, so feel free to adjust the amounts of any of the spices to suit your taste.

Cormarye.

Take Coriander, Caraway small ground, Powder of Pepper and garlic ground in red wine, muddle all this together and salt it, take loins of Pork raw and flay off the skin, and prick it well with a knife and lay it in the sauce, roast thereof what thou wilt, & keep that that falleth therefrom in the roasting and seeth it in a little pot with fair broth, & serve it forth with the roast anon.

— The Forme of Cury, 1390

January 27, 2026

Did People in the Middle Ages Drink Water?

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 1 Aug 2025A brew of barley, licorice, figs, and sugar

City/Region: France

Time Period: 1393The myth persists that everyone was drunk in the Middle Ages because no one drank water, only alcohol. While many people preferred to drink ale, wine, or mead, people drank water all the time. Having a source of fresh, clean water was the basis of the location of many cities and towns.

Clean water isn’t just an issue of the past, either. Today, 1 in 10 people don’t have access to clean water. For the month of August, I’m joining thousands of creators across the internet to form Team Water with the goal of raising $40 million to supply 2 million people with clean water which will flow for decades. You can support Team Water by donating at teamwater.org, or by watching and sharing the episode for this recipe. I’ll be donating all of the ad revenue from this video to Team Water!

This sweet tisane is an herbal tea made with barley, licorice root, figs, and sugar. I really enjoyed it, even though the flavor of the licorice and figs didn’t come through. It kind of reminds me of the milk after you’ve eaten a bowl of Raisin Bran, which I like.

Sweet tisane.

Take some water and boil it, then for each septier of water add one generous bowl of barley — it does not matter if it is all hulled — and two parisis’ worth of licorice; item, also figs. Boil until the barley bursts, then strain through two or three pieces of linen, and put plenty of rock sugar in each goblet. The barley that remains can be fed to poultry to fatten them.

— Le Ménagier de Paris, 1393

January 23, 2026

QotD: The peasant – historically, the overwhelming majority of humanity

Prior to the industrial revolution, peasant farmers of varying types made up the overwhelming majority of people in settled societies (the sort with cities and writing). And when I say overwhelming, I mean overwhelming: we generally estimate these societies to have consisted of upwards of 80% peasant farmers, often as high as 90 or even 95%. Yet when we talk about these periods, we are often focused on aristocrats, priests, knights, warriors, kings and literate bureaucrats, the sort of folks who write to us or on smiths, masons and artists, the sort of folk whose work sometimes survives for us to see. But this series is going to be about what life was like for the great majority of people who lived in small farming households.

We’re actually doing two things in this series. First, of course, we’ll be discussing what we know about the patterns of life for peasant households. But we’re also laying out a method. The tricky thing with discussing peasants, after all, is that they generally do note write to us (not being literate) and the writers we do have from the past are generally uninterested in them. This is a mix of snobbery – aristocrats rarely actually care very much how the “other half” (again, the other 95%) live – but also a product of familiarity: it was simply unnecessary to describe what life for the peasantry was like because everyone could see it and most people were living it. But that can actually make investigating the lives of these farming folks quite hard, because their lives are almost never described to us as such. Functionally no one in antiquity or the middle ages is writing a biography of a small peasant farmer who remained a peasant farmer their whole life.1 But the result is that I generally cannot tell you the story of a specific ancient or medieval small peasant farmer.

What we can do, however is uncover the lives of these peasant households through modelling. Because we mostly do have enough scattered evidence to chart the basic contours, as very simply mathematical models, of what it was like to live in these households: when one married, the work one did, the household size, and so on. So while I cannot pick a poor small farmer from antiquity and tell you their story, I can, in a sense, tell you the story of every small farmer in the aggregate, modelling our best guess at what a typical small farming household would look like.

So that’s what we’re going to do here. This week we’re going to introduce our basic building blocks, households and villages, and talk about their shape and particularly their size. Then next week (hopefully), we’ll get into marriage, birth and mortality patterns to talk about why they are the size they are. Then, ideally, the week after that, we’ll talk about labor and survival for these households: how they produce enough to survive, generation to generation and what “survival” means. And throughout, we’ll get a sense of both what a “typical” peasant household might look and work like, and also the tools historians use to answer those questions.

But first, a necessary caveat: I am a specialist on the Roman economy and so my “default” is to use estimates and data from the Roman Republic and Roman Empire (mostly the latter). I have some grounding in modelling other ancient and medieval economies in the broader Mediterranean, where the staple crops are wheat and barley (which matters). So the models we’re going to set up are going to be most applicable in that space: towards the end of antiquity in the Mediterranean. They’ll also be pretty applicable to the European/Mediterranean Middle Ages and some parts – particularly mortality patterns – are going to apply universally to all pre-modern agrarian societies. I’ll try to be clear as we move what elements of the model are which are more broadly universal and which are very context sensitive (meaning they differ place-to-place or period-to-period) and to the degree I can say, how they vary. But our “anchor point” is going to be the Romans, operating in the (broadly defined) iron age, at the tail end of antiquity.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Life, Work, Death and the Peasant, Part I: Households”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2025-07-11.

- And, as we’ll see, these societies generally have almost no social mobility, so extremely few – functionally none – of the sort of people who write to us will have ever been peasant farmers.

January 10, 2026

A Short Tour of Roman London

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 19 Sept 2025The ruins of Londinium – London’s Roman predecessor – are not spectacular. But they are extremely interesting …

0:00 Introduction

0:40 City walls

1:47 St. Magnus the Martyr

2:26 Monument to the Great Fire

3:12 Leadenhall Market

4:10 London Mithraeum

6:19 Bank of England

7:08 Guildhall Amphitheater

8:14 The Gherkin

December 31, 2025

QotD: The cloth trade in the ancient and medieval world

Fabric as a finished product is somewhat different from the other products (grain and iron) we’ve discussed in this series so far. Bulk grain is a commodity – which means that one kilogram of grain is pretty much like the next. When grain gets traded in bulk it is because of differences in supply, not generally because grain in one region or other is particularly tasty. Consequently, you only get bulk grain trading when one area is producing a surplus and another not producing enough. The same is more loosely true of iron; Iron wasn’t a perfect commodity in the pre-modern world since some ores produced better quality metal than others and some trade in high quality ores or metal (like wootz) happened. But for every-day use, local iron was generally good enough and typically available. Iron could be – and often was – treated as a commodity too.

Fabric is not like that. While the lower classes will often have had to make do with whatever sorts of cloth is produced cheaply and locally, for people who could afford to have some choices the very nature of textile production produces lots of regional differences which incentivized trade. Almost everything about textile production is subject to regional variations:

- What fibers are being used. Major wool and linen producing regions tended to be separate, with wool (and sheep) in colder climates and uplands while (as noted) flax tended to be grown in warmer river-valleys with rich alluvial soil. Meanwhile, the cotton-and-silk producing regions generally (with some notable exceptions, mind) did not overlap with the wool and linen producing regions.

- The nature of the local fibers. We’ll get to some specific examples in a moment but ancient and medieval writers were well aware that different growing conditions, breeds of sheep or flax, climate and so on produced fibers of subtly different qualities. Consequently, even with the exact same processes, cloth produced in one region might be different from cloth produced in another region. But the processes were almost never the same because …

- Local variation in production processes. Again, we’ll have some examples in a moment, but the variance here could be considerable. As we’ve seen, the various tasks in cloth production are all pretty involved and give a lot of room for skill and thus for location variations in methods and patterns. One might see different weaving patterns, different spinning techniques, different chemical treatments, different growing or shearing methods and so on producing fabrics of different qualities which might thus be ideal for different purposes.

- Dye methods and availability. And as we discussed last time, available dyestuffs (and the craft knowledge about how to use them) was also often very local, leading to certain colors or patterns of color being associated with different regions and creating a demand for those. While it was often possible to ship dyestuffs (although not all dyestuffs responded well to long-distance shipping), it was often more economical to shift dyed fabric.

Added on top of this, fabric is a great trade-good. It is relatively low bulk when wrapped around in a roll (a bolt of fabric might hold fabric anywhere from 35-91m long and 100-150cm wide. Standard English broadcloth was 24 yards x 1.75 yards; that’s a lot of fabric in both cases!) and could be very high value, especially for high quality or foreign fabrics (or fabrics dyed in rare or difficult colors). Moreover, fabric isn’t perishable, temperature sensitive (short of an actual fire) or particularly fragile, meaning that as long as it is kept reasonably dry it will keep over long distances and adverse conditions. And everyone needs it; fabrics are almost perfect stock trade goods.

Consequently, we have ample evidence to the trade of both raw fibers (that is, wool or flax rovings) and finished fabrics from some of the earliest periods of written records (spotting textile trade earlier than that is hard, since fabric is so rarely preserved in the archaeological record). Records from Presargonic Mesopotamia (c. 2400-2300) record wool trading both between Mesopotamian cities but wool being used as a trade good for merchants heading through the Persian Gulf, to Elam and appears to have been one of, if not the primary export good for Sumerian cities (W. Sallaberger in Breniquet and Michel, op. cit.). More evidence comes later, for instance, palace letters and records from the Old Babylonian Empire (1894-1595) reporting the commercialization of wool produced under the auspices of the palace or the temple (Mesopotamian economies being centralized in this way in what is sometimes termed a “redistribution economy” though this term and the model it implies is increasingly contested as it becomes clearer from our evidence that economic activity outside of the “palace economy” also existed) and being traded with other cities like Sippar (on this, note K. De Graef and C. Michel’s chapters in Breniquet and Michel, op. cit.).

Pliny the Elder, in detailing wool and linen producing regions provides some clues for the outline of the cloth trade in the Roman world. Pliny notes that the region between the Po and Ticino river (in Northern Italy) produced linen that was never bleached while linen from Faventia (modern Faenza) was always bleached and renowned for its whiteness (Pliny, NH 19.9). Linen from Spain around Tarragona was thought by Pliny to be exceptionally fine while linens from Zeola (modern Oiartzun, Spain) was particularly durable and good for making nets (Pliny, NH 19.10). Meanwhile Egyptian flax he notes is the least strong but the most fine and thus the most expensive (Pliny NH 19.14). Meanwhile on wool, Pliny notes that natural wool color varied by region; the best white wool he thought came from the Po River valley, the best black wool from the Alps, the best red wool from Asia Minor, the best brown wool from Canusium (in Apulia) and so on (Pliny, Natural History 8.188-191). He also notes different local manufacture processes producing different results, noting Gallic embroidery and felting (NH 8.192). And of course, being Pliny, he must rank them all, with wool from Tarentum and Canusium (Taranto and Canosa di Puglia) being the best, followed more generally by Italian wools and in third place wools from Miletus in Asia Minor (Pliny NH 8.190). Agreement was not quite universal, Columella gives the best wools as those from Miletus, Calabria, and Apulia, with Tarantine wool being the best, but demoting the rest of the Italian wools out of the list entirely (Col. De Re Rust. 7.2).

In medieval Europe, wool merchants were a common feature of economic activity in towns, with the Low Countries and Northern Italy in particular being hubs of trade in wool and other fabrics (Italian ports also being one of the major routes by which cottons and silks from India and China might find their way, via the Mediterranean, to European aristocrats). Wool produced in Britain (which was a major production center) would be shipped either as rovings or as undyed “broadcloths” (called “whites”) to the Low Countries for dyeing and sale abroad (though there was also quite a lot of cloth dyeing happening in Britain as well).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part IVb: Cloth Money”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-04-09.

December 28, 2025

QotD: The Middle Ages saw rebellions but no revolutions

At some point in this space, we discussed the difference between a rebellion and a revolution. Drawing on Michael Walzer’s key work The Revolution of the Saints, I argued that a true revolution requires ideology, as it’s an attempt to fundamentally change society’s structure.

Therefore there were no revolutions in the Middle Ages or the Ancient World, only rebellions — even a nasty series of civil wars like The Wars of the Roses were merely bloody attempts to replace one set of rulers with another, without comment on the underlying structure. A medieval usurpation couldn’t help but raise questions about “political theory” in the broadest sense — how can God’s anointed monarch be overthrown? — but medieval usurpers understood this: They always presented the new boss as the true, legitimate king by blood. I forget how e.g. Henry IV did it — Wiki’s not clear — but he did, shoehorning himself into the royal succession somehow.

Combine that with Henry’s obvious competence, Richard II’s manifest in-competence, and Henry’s brilliant manipulation of the rituals of kingship, and that was good enough; his strong pimp hand took care of the rest. Henry IV was a legitimate king because he acted like a legitimate king.

A revolution, by contrast, aims to change fundamental social relations. That’s why medieval peasant rebellions always failed. Wat Tyler had as many, and as legitimate, gripes against Richard II as Henry Bolingbroke did, but unlike Henry’s, Tyler’s gripes couldn’t really be addressed by a change of leadership — they were structural. 200 years later, and the rebels were now revolutionaries, willing to give structural change a go.

Severian, “¡Viva la Revolución!”, Founding Questions, 2025-02-27.

December 21, 2025

QotD: Renfaires

They had spent the day at the Renaissance Festival, and my wife was still shuddering over the event. I did a story on the event almost ten years ago, and while it had its annoying aspects, it was a rather benign and gentle thing. Apparently it’s changed, and now it’s full of louts and Goths and lewdenesse; half-naked Creative Anachronism types happy to unfurl their great white guts for all to see, fleshy snaggle-toothed watermelon-jugged exhibitionists in costumes more appropriate for a bar called The Teatery, theatrical bits full of cheap single-entendres, grim meat-shops that swapped a fiver for a jot of pale stringy meat and an indifferent shrug. All this and ankle-deep mud in the parking lot. At least it’s authentic.

James Lileks, The Bleat, 2005-09-05.

December 17, 2025

History of Britain X: King Arthur, History or Myth?

Thersites the Historian

Published 7 Aug 2025In this lecture, I discuss the historicity (or lack thereof) of the Arthurian myth.

(more…)

December 16, 2025

QotD: Arms and the (pre-modern) man (at arms)

… how much value might a heavily armored fighter or warrior be carrying around on their backs in the real world? Because I think the answer here is informative.

Here we do have some significant price data, but of course its tricky to be able to correlate a given value for arms and armor with something concrete like wages in every period, because of course prices are not stable. But here are some of the data points I’ve encountered:

We don’t have good Roman price data from the Republic or early/high Empire, unfortunately (and indeed, the reason I have been collecting late antique and medieval comparanda is to use it to understand the structure of earlier Roman costs). Hugh Elton1 notes that a law of Valens (r. 364-378) assessed the cost of clothing, equipment and such for a new infantry recruit to be 6 solidi and for a cavalryman, 13 solidi (the extra 7 being for the horse). The solidus was a 4.5g gold coin at the time (roughly equal to the earlier aureus) so that is a substantial expense to kit out an individual soldier. For comparison, the annual rations for soldiers in the same period seem to have been 4-5 solidi, so we might suggest a Roman soldier is wearing something like a year’s worth of living expenses.2

We don’t see a huge change in the Early Middle Ages either. The seventh century Lex Ripuaria,3 quotes the following prices for military equipment: 12 solidi for a coat of mail, 6 solidi for a metal helmet, 7 for a sword with its scabbard, 6 for mail leggings, 2 solidi for a lance and shield for a rider (wood is cheap!); a warhorse was 12 solidi, whereas a whole damn cow was just 3 solidi. On the one hand, the armor for this rider has gotten somewhat more extensive – mail leggings (chausses) were a new thing (the Romans didn’t have them) – but clearly the price of metal equipment here is higher: equipping a mailed infantryman would have some to something like 25ish solidi compared to 12 for the warhorse (so 2x the cost of the horse) compared to the near 1-to-1 armor-to-horse price from Valens. I should note, however, warhorses even compared to other goods, show high volatility in the medieval price data.

As we get further one, we get more and more price data. Verbruggen (op. cit. 170-1) also notes prices for the equipment of the heavy infantry militia of Bruges in 1304; the average price of the heavy infantry equipment was a staggering £21, with the priciest item by far being the required body armor (still a coat of mail) coming in between £10 and £15. Now you will recall the continental livre by this point is hardly the Carolingian unit (or the English one), but the £21 here would have represented something around two-thirds of a year’s wages for a skilled artisan.

Almost contemporary in English, we have some data from Yorkshire.4 Villages had to supply a certain number of infantrymen for military service and around 1300, the cost to equip them was 5 shillings per man, as unarmored light infantry. When Edward II (r. 1307-1327) demanded quite minimally armored men (a metal helmet and a textile padded jack or gambeson), the cost jumped four-fold to £1, which ended up causing the experiment in recruiting heavier infantry this way to fail. And I should note, a gambeson and a helmet is hardly very heavy infantry!

For comparison, in the same period an English longbowman out on campaign was paid just 2d per day, so that £1 of kit would have represented 120 days wages. By contrast, the average cost of a good quality longbow in the same period was just 1s, 6d, which the longbowman could earn back in just over a week.5 Once again: wood is cheap, metal is expensive.

Finally, we have the prices from our ever-handy Medieval Price List and its sources. We see quite a range in this price data, both in that we see truly elite pieces of armor (gilt armor for a prince at £340, a full set of Milanese 15th century plate at more than £8, etc) and its tricky to use these figures too without taking careful note of the year and checking the source citation to figure out which region’s currency we’re using. One other thing to note here that comes out clearly: plate cuirasses are often quite a bit cheaper than the mail armor (or mail voiders) they’re worn over, though hardly cheap. Still, full sets of armor ranging from single to low-double digit livres and pounds seem standard and we already know from last week’s exercise that a single livre or pound is likely reflecting a pretty big chunk of money, potentially close to a year’s wage for a regular worker.

So while your heavily armored knight or man-at-arms or Roman legionary was, of course, not walking around with the Great Pyramid’s worth of labor-value on his back, even the “standard” equipment for a heavy infantryman or heavy cavalryman – not counting the horse! – might represent a year or even years of a regular workers’ wages. On the flipside, for societies that could afford it, heavy infantry was worth it: putting heavy, armored infantry in contact with light infantry in pre-gunpowder warfare generally produces horrific one-sided slaughters. But relatively few societies could afford it: the Romans are very unusual for either ancient or medieval European societies in that they deploy large numbers of armored heavy infantry (predominately in mail in any period, although in the empire we also see scale and the famed lorica segmentata), a topic that forms a pretty substantial part of my upcoming book, Of Arms and Men, which I will miss no opportunity to plug over the next however long it takes to come out.6 Obviously armored heavy cavalry is even harder to get and generally restricted to simply putting a society’s aristocracy on the battlefield, since the Big Men can afford both the horses and the armor.

But the other thing I want to note here is the social gap this sort of difference in value creates. As noted above with the bowman’s wages, it would take a year or even years of wages for a regular light soldier (or civilian laborers of his class) to put together enough money to purchase the sort of equipment required to serve as a soldier of higher status (who also gets higher pay). Of course it isn’t as simple as, “work as a bowman for a year and then buy some armor”, because nearly all of that pay the longbowman is getting is being absorbed by food and living expenses. The result is that the high cost of equipment means that for many of these men, the social gap between them and either an unmounted man-at-arms or the mounted knight is economically unbridgeable.7

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, January 10, 2025”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2025-01-10.

- Warfare in Roman Europe AD 350-425 (1996), 122.

- If you are wondering why I’m not comparing to wages, the answer is that by this point, Roman military wages are super irregular, consisting mostly of donatives – special disbursements at the accession of a new emperor or a successful military campaign – rather than regular pay, making it really hard to do a direct comparison.

- Here my citation is not from the text directly, but Verbruggen, The Art of War in Western Europe during the Middle Ages (1997), 23.

- From Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages (1996).

- These prices via Hardy, Longbow: A Social and Military History (1992).

- Expect it no earlier than late this year; as I write this, the core text is actually done (but needs revising), but that’s hardly the end of the publication process.

- Man-at-arms is one of those annoyingly plastic terms which is used to mean “a man of non-knightly status, equipped in the sort of kit a knight would have”, which sometimes implies heavy armored non-noble infantry and sometimes implies non-knightly heavy cavalry retainers of knights and other nobles.

December 14, 2025

QotD: Why are Castles?

Castles differ from that other standby of medieval fortifications — city walls — in one crucial way, and that difference sheds a lot of light on their military application.

A massive city wall, like the one shown above, has the very clear purpose of limiting access to a city or town. Close the gates, and no one can get in. Try to get in, and we’ll shoot you! The walls are meant to protect the settlement, both its inhabitants as well as its structures and physical wealth.

A castle, on the other hand, has a much smaller footprint than a city. It might only be a few buildings and a courtyard. Indeed, as we’ll see later in the series, the earliest castles (the classic “motte and bailey” design) were relatively small fortifications of earth and timber, capable of being built in a matter of days.

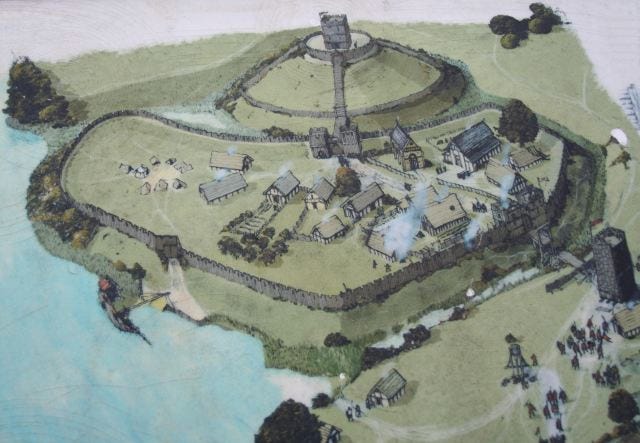

Image of a motte and bailey style castle. This particular one would take much longer than a few days to make, but it’s worth noting that even this “primitive” castle of timber and earth would have been a serious problem for any attacker. (Duncan Grey – Display Board of Huntingdon Hill Motte and Bailey Castle – CC BY-SA 2.0).

Especially if a lord was not in residence, a castle might only have a garrison of a few dozen, a far cry from the walls around urban centers that protected thousands or tens of thousands of lives!

So why bother?

Because, unlike a city wall which is meant to defend everything within it, a castle isn’t built in order to protect a tiny bit of land on top of a hill. Instead (say it with me, class): a castle is built to deny an enemy freedom of movement.

It’s not about what’s inside the walls. It’s about what’s outside the walls.

A castle allows you to control a disproportionately large area of land.

That control matters a great deal, because land was the source of wealth in pre-modern contexts. In societies where 80-95% of the populace were farmers, wealth and power came from controlling arable land. Capital did not derive principally from urban centers — wealthy and valuable as those were.1

Before we go further into how that impacts war and politics, I want to take a moment and dig deeper into why a castle allows its owner to control the land, because it’s something that’s usually glossed over, and understanding this dynamic will have a significant bearing on everything else we talk about here.

The Ugly Nature of Rule

As I’ve explained before, in order to actually rule an area, the ruler needs to have a monopoly on legitimate violence within that area. The emphasis here is on legitimate violence, which is significantly different than just “brute force”; force alone will always be a temporary and unstable method of rule. [You can read this explainer for more on that.] A ruler’s legitimacy allows that monopoly to continue unopposed.

One of the main reasons why a ruler needs that monopoly is that it allows for the collection of resources for use by the state. I’m going to lump all this together under the word “taxes”, but to be clear: in pre-modern societies, “taxes” could include manual labor commitments, payments in kind (in crops, in material, etc.), or in cash.

For all that, the ruler needs his agents to have unfettered access to the country he aims to rule; his tax collectors, law enforcers, merchants, judges, and certainly his lords and military all need to be able to move freely throughout the realm in order to do all the necessary business of maintaining law, order, and the collection of taxes.

Those are the most basic elements of statehood, the most basic mechanism of ordinary, everyday governing.

Castles fit into that system the same as any other governmental or administrative center: it’s a place to collect and store resources, a place for state agents to shelter, a locale for arbitration of justice, a residence for a lord … A castle can be a courthouse, police station, secret service listening post, governor’s mansion, and revenue service office all in one.

And a castle is fortified for much the same reasons that governmental buildings across history have always been fortified.

Even if the majority of a subject populace believes your rule is legitimate — a big if! — then there will still be people who chafe at the collection of taxes and who feel wronged by the administration of justice. Those outliers — if indeed they even are outliers — might try something stupid, like taking back their resources or stabbing your

thugspeace-loving tax collectors. Better to have everything locked up, right?And if the castle is large, and visibly imposing? Well that doesn’t hurt, does it?

That’s the every-day purpose of castles, at least in the sense that on any average Tuesday morning, that’s what the castle is for. That’s what people in the castle are doing. Ruling.

Eric Falden, “What Were Castles Actually For?”, Falden’s Forge, 2025-07-29.

1. There are exceptions, of course, such as thassalocratic polities. But sea-faring societies don’t built castles and are therefore WAY outside the bounds of this discussion.

December 9, 2025

QotD: The development of army discipline and drill in pre-modern armies

The usual solution to this difficulty [maneuvring units on the battlefield] often goes by the terms “drill” or “discipline” though we should be clear here exactly what we mean. Discipline in particular has a number of meanings: it can mean the personal restraint of an individual, a system of rewards and punishments (and the effects of that system; the punishments are typically corporal) and what we are actually interested in: the ability of a large body of humans to move and act effectively in concert (all of these meanings are present to some degree in the root Latin word disciplina). For clarity’s sake then I am going to borrow a term (as is my habit) from W. Lee, Waging War (2016), synchronized discipline to describe the “humans moving an acting in concert” component of discipline that we’re most interested in here. That said, it is worth noting that those three components: personal restraint, corporal punishments and the synchronized component of discipline are frequently (but not universally) associated for reasons we’ll get to, not merely in the Roman concept of disciplina, but note also for instance their close association in Sun Tzu’s Art of War in the first chapter (section 13).

The reason we cannot just call this “drill” is because while drill is the most common way agrarian societies produce this result, it is not the only way to this end. For instance as we’ve discussed before, steppe nomads could achieve a very high degree of coordination and synchronization without the same formal systems of drill because the training that produced that coordination was embedded in their culture (particularly in hunting methods) and so young steppe nomad males were acculturated into the synchronicity that way. That said for the rest of this we’re going to place those systems aside and mostly focus on synchronized discipline as a result of drill because for most armies that developed a great deal of synchronized discipline, that’s how they did it.

Fundamentally the principle behind using drill to build synchronized discipline is that the way to get a whole lot of humans to act effectively in concert together is to force them to practice doing exactly the things they’ll be asked to do on the battlefield a lot until the motions are practically second nature. Indeed, the ideal in developing this kind of drill was often to ingrain the actions the soldiers were to perform so deeply that in the midst of the terror of battle when they couldn’t even really think straight those soldiers would fall back on simply mechanically performing the actions they were trained to perform. That in turn creates an important element of predictability: an individual soldier does not need to be checking their action or position against the others around them as much because they’ve done this very maneuver with these very fellows and so already know where everyone is going to be.

The context that drill tends to emerge in (this is an idea invented more than once) tends to give it a highly regimented, fairly brutal character. For instance in early modern Europe, the structure of drill for gunpowder armies was conditioned by elite snobbery: European officer-aristocrats (in many cases the direct continuation of the medieval aristocracy) had an extremely poor view of their common soldiers (drawn from the peasantry). Assuming they lacked any natural valor, harsh drill was settled upon as a solution to make the actions of battle merely mechanical, to reduce the man to a machine. Roman commanders seemed to have thought somewhat better of their soldiers’ bravery, but assumed that harsh discipline was necessary to control, restrain and direct the native fiery virtus (“strength/bravery/valor”) of the common soldier who, unlike the aristocrat, could not be expected to control himself (again, in the snobbish view of the aristocrats).

In short, drill tends to appear in highly stratified agrarian societies, the very nature of which tends to mean that drill is instituted by a class of aristocrats who have at best a dim view of their common soldiers. Consequently, while the core of drill is to simply practice the actions of battle over and over again until they become natural, drill tends to also be encrusted with lots of corporal punishments and intense regulation as a product of those elite attitudes. And though it falls outside of our topic today it seems worth noting that our systems of drill to produce synchronized discipline have the same roots (deriving from early modern musket drill).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Total Generalship: Commanding Pre-Modern Armies, Part IIIa”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-17.