These strategic (and operational) considerations dictate some of the tactical realities of most sieges. The attacker’s army is generally going to be larger and stronger, typically a lot larger and stronger, because if the two sides were anywhere near parity with each other the defender would risk a battle rather than submit to a siege. Thus the main problem the attacker faces is access: if the attacker can get into the settlement, that will typically be sufficient to ensure victory.

The problem standing between that attacking army and access was, of course, walls (though as we will see, walls rarely stand alone as part of a defensive system). Even very early Neolithic settlements often show concerns for defense and signs of fortification. The oldest set of city walls belong to one of the oldest excavated cities (which should tell us how short the interval between the development of large population centers and the need to fortify those population centers was), Jericho in the West Bank. The site was inhabited beginning around 10,000 BC and the initial phase of construction on what appears to be a city wall reinforced with a defensive tower was c. 8000 BC. It is striking just how substantial the fortifications are, given how early they were constructed: initially the wall was a 3.6m stone perimeter wall, supported by a 8.5m tall tower, all in stone. That setup was eventually reinforced with a defensive ditch dug 2.7m deep and 8.2m wide cutting through the bedrock (that is a ditch even Roel Konijnendijk could be proud of!), by which point the main wall was enhanced to be some 1.5-2m thick and anywhere from 3.7-5.2m high. That is a serious wall and unlikely the first defensive system protecting the site; chances are there were older fortifications, perhaps in perishable materials, which do not survive. Simply put, no one starts by building a 4m by 2m stone wall reinforced by a massive stone tower and a huge ditch through the bedrock; clearly city walls [were] something people had already been thinking about for some time.

I want to stress just how deep into the past a site like Jericho is. At 8000 BC, Jericho’s wall and tower pre-date the earliest writing anywhere (the Kish tablet, c. 3200 BC) by c. 4,800 years. The tower of Jericho was more ancient to the Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2600 BC), than the Great Pyramid is to us. In short, the problem of walled cities – and taking walled cities – was a very old problem, one which predated writing by thousands of years. By the time the arrival of writing allows us to see even a little more clearly, Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Levant are already filled with walled cities, often with stunningly impressive stone or brick walls. Gilgamesh (r. 2900-2700 BC) brags about the walls of Uruk in the Epic of Gilgamesh (composed c. 2100) as enclosing more than three square miles and being made of superior baked bricks (rather than inferior mudbrick); there is evidence to suggest, by the by, that the historical Gilgamesh (or Bilgames) did build Uruk’s walls and that they would have lived up to the poem’s billing. Meanwhile, in Egypt, we have artwork like the Towns Palette, which appears to commemorate the successful sieges of a number of walled towns

So a would-be agrarian conqueror in Egypt, Mesopotamia or the Levant, from well before the Bronze Age would have already had to contest with the problem of how to seize fortified towns. Of course depictions like these make it difficult to reconstruct siege tactics (the animals on the Towns Palette likely represent armies, rather than a strategy of “use a giant bird as a siege weapon”), so we’re going to jump ahead to the (Neo)Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC; note that we are jumping ahead thousands of years).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part I: The Besieger’s Playbook”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-29.

February 10, 2026

QotD: The (historical) walls of Jericho

December 31, 2025

QotD: The cloth trade in the ancient and medieval world

Fabric as a finished product is somewhat different from the other products (grain and iron) we’ve discussed in this series so far. Bulk grain is a commodity – which means that one kilogram of grain is pretty much like the next. When grain gets traded in bulk it is because of differences in supply, not generally because grain in one region or other is particularly tasty. Consequently, you only get bulk grain trading when one area is producing a surplus and another not producing enough. The same is more loosely true of iron; Iron wasn’t a perfect commodity in the pre-modern world since some ores produced better quality metal than others and some trade in high quality ores or metal (like wootz) happened. But for every-day use, local iron was generally good enough and typically available. Iron could be – and often was – treated as a commodity too.

Fabric is not like that. While the lower classes will often have had to make do with whatever sorts of cloth is produced cheaply and locally, for people who could afford to have some choices the very nature of textile production produces lots of regional differences which incentivized trade. Almost everything about textile production is subject to regional variations:

- What fibers are being used. Major wool and linen producing regions tended to be separate, with wool (and sheep) in colder climates and uplands while (as noted) flax tended to be grown in warmer river-valleys with rich alluvial soil. Meanwhile, the cotton-and-silk producing regions generally (with some notable exceptions, mind) did not overlap with the wool and linen producing regions.

- The nature of the local fibers. We’ll get to some specific examples in a moment but ancient and medieval writers were well aware that different growing conditions, breeds of sheep or flax, climate and so on produced fibers of subtly different qualities. Consequently, even with the exact same processes, cloth produced in one region might be different from cloth produced in another region. But the processes were almost never the same because …

- Local variation in production processes. Again, we’ll have some examples in a moment, but the variance here could be considerable. As we’ve seen, the various tasks in cloth production are all pretty involved and give a lot of room for skill and thus for location variations in methods and patterns. One might see different weaving patterns, different spinning techniques, different chemical treatments, different growing or shearing methods and so on producing fabrics of different qualities which might thus be ideal for different purposes.

- Dye methods and availability. And as we discussed last time, available dyestuffs (and the craft knowledge about how to use them) was also often very local, leading to certain colors or patterns of color being associated with different regions and creating a demand for those. While it was often possible to ship dyestuffs (although not all dyestuffs responded well to long-distance shipping), it was often more economical to shift dyed fabric.

Added on top of this, fabric is a great trade-good. It is relatively low bulk when wrapped around in a roll (a bolt of fabric might hold fabric anywhere from 35-91m long and 100-150cm wide. Standard English broadcloth was 24 yards x 1.75 yards; that’s a lot of fabric in both cases!) and could be very high value, especially for high quality or foreign fabrics (or fabrics dyed in rare or difficult colors). Moreover, fabric isn’t perishable, temperature sensitive (short of an actual fire) or particularly fragile, meaning that as long as it is kept reasonably dry it will keep over long distances and adverse conditions. And everyone needs it; fabrics are almost perfect stock trade goods.

Consequently, we have ample evidence to the trade of both raw fibers (that is, wool or flax rovings) and finished fabrics from some of the earliest periods of written records (spotting textile trade earlier than that is hard, since fabric is so rarely preserved in the archaeological record). Records from Presargonic Mesopotamia (c. 2400-2300) record wool trading both between Mesopotamian cities but wool being used as a trade good for merchants heading through the Persian Gulf, to Elam and appears to have been one of, if not the primary export good for Sumerian cities (W. Sallaberger in Breniquet and Michel, op. cit.). More evidence comes later, for instance, palace letters and records from the Old Babylonian Empire (1894-1595) reporting the commercialization of wool produced under the auspices of the palace or the temple (Mesopotamian economies being centralized in this way in what is sometimes termed a “redistribution economy” though this term and the model it implies is increasingly contested as it becomes clearer from our evidence that economic activity outside of the “palace economy” also existed) and being traded with other cities like Sippar (on this, note K. De Graef and C. Michel’s chapters in Breniquet and Michel, op. cit.).

Pliny the Elder, in detailing wool and linen producing regions provides some clues for the outline of the cloth trade in the Roman world. Pliny notes that the region between the Po and Ticino river (in Northern Italy) produced linen that was never bleached while linen from Faventia (modern Faenza) was always bleached and renowned for its whiteness (Pliny, NH 19.9). Linen from Spain around Tarragona was thought by Pliny to be exceptionally fine while linens from Zeola (modern Oiartzun, Spain) was particularly durable and good for making nets (Pliny, NH 19.10). Meanwhile Egyptian flax he notes is the least strong but the most fine and thus the most expensive (Pliny NH 19.14). Meanwhile on wool, Pliny notes that natural wool color varied by region; the best white wool he thought came from the Po River valley, the best black wool from the Alps, the best red wool from Asia Minor, the best brown wool from Canusium (in Apulia) and so on (Pliny, Natural History 8.188-191). He also notes different local manufacture processes producing different results, noting Gallic embroidery and felting (NH 8.192). And of course, being Pliny, he must rank them all, with wool from Tarentum and Canusium (Taranto and Canosa di Puglia) being the best, followed more generally by Italian wools and in third place wools from Miletus in Asia Minor (Pliny NH 8.190). Agreement was not quite universal, Columella gives the best wools as those from Miletus, Calabria, and Apulia, with Tarantine wool being the best, but demoting the rest of the Italian wools out of the list entirely (Col. De Re Rust. 7.2).

In medieval Europe, wool merchants were a common feature of economic activity in towns, with the Low Countries and Northern Italy in particular being hubs of trade in wool and other fabrics (Italian ports also being one of the major routes by which cottons and silks from India and China might find their way, via the Mediterranean, to European aristocrats). Wool produced in Britain (which was a major production center) would be shipped either as rovings or as undyed “broadcloths” (called “whites”) to the Low Countries for dyeing and sale abroad (though there was also quite a lot of cloth dyeing happening in Britain as well).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part IVb: Cloth Money”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-04-09.

October 18, 2025

QotD: Civilizational survival after the Bronze Age Collapse

If post-Collapse Egypt is Britain, then perhaps post-Collapse Phoenicia is America: a relative backwater, dwarfed by the Great Powers of its day, that suddenly leaps to global prominence when the opportunity arises … but in doing so, changes in some very fundamental ways. Which raises a question about Cline’s subtitle, “The Survival of Civilizations”: what does it actually mean for a civilization to survive?

Sometimes the answer is obvious. The Assyrians and Babylonians clearly survived the Collapse: if you compare their architecture, inscriptions, artwork, settlement patterns, and political structures from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age, they are recognizably the same people doing the same things and talking about them in the same way. The Egyptians, too, are plainly the same civilization throughout their (very long!) history, even if they were notably weaker and less organized after the Collapse. The Hittites, just as obviously, did not survive (at least not outside their tiny rump states in northern Syria). But the Greeks and the Phoenicians are both murkier cases, albeit in very different ways.

On the one hand, Mycenaean civilization — the palace economy and administration, the population centers, the monumental architecture, the writing — indisputably vanished. The Greeks painstakingly rebuilt civilization over several hundred years, but they did it from scratch: there is no political continuity from the Mycenaean kingdoms to the states of the archaic or classical worlds. And yet as far as we can tell, there was substantial cultural continuity preserved in language and myth. Admittedly, “as far as we can tell” is doing a lot of work here: Linear B was only ever used for administrative record-keeping, so we can’t compare the Mycenaeans’ literary and political output to their successors the way we can in Assyria or Egypt. We can’t be sure that the character, the vibe, the flavor of the people remained. But the historical and archaeological records of the later Greeks contain enough similarities with the descendants of the Mycenaeans’ Indo-European brethren that the answer seems to be yes.

By contrast, civilization never collapsed in central Canaan. No one ever stopped having kings, writing, building in stone, or making art. The Bronze Age population centers were continuously occupied right up to … well, now. And yet their way of life shifted dramatically, to the point that we call them by a new name and consider them a different people. Cline thinks this is a success story: borrowing an analytical framework from a 2012 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, he praises their “transformation”,1 which “include[d] actions that change the fundamental attributes of a system in response to actual or expected impacts”. (The Assyrians, by contrast, merely “adapted”, while the Egyptians barely “coped”.) But does there come a point when the change is so great, so fundamental, you’re no longer the same civilization? Can the Ship of Theseus really be said to have “survived”?

In the final section of his book, titled “Mycenaeans or Phoenicians”, Cline asks how we’ll react to the societal collapse we all sort of know is coming sooner or later. Our world just is too complicated, too interconnected, to survive a really massive shock (or, as in the Late Bronze Age, a “perfect storm” of smaller ones). Even the relatively mild disruptions of the past few years have revealed fragilities and vulnerabilities that we’ve done nothing to shore up since. Of course, he has an answer: Transform! Innovate! Flourish amidst chaos! Become a new iteration of yourself, like the bog-standard Canaanite cities that reinvented themselves as an Iron Age mercantile superpower and turned the Mediterranean into a “Phoenician lake”. But at what price?

Or, to think of it another way, what would you prefer for your society five hundred years from now?

Behind Door Number One: governmental collapse, abandonment of the population centers, dramatic reduction in societal complexity, and then a long, slow rebuilding where your time and your people are remembered only as myth — but when civilization is restored, it’ll be by people whose the desires, values, attitudes, and beliefs, their most basic ways of understanding the world, are still recognizably yours. They may have no idea you ever lived, but the stories that move your heart will move theirs too.

And behind Door Number Two: expansion, prosperity, and a new starring role on the world stage — but a culture so thoroughly reoriented towards that new position that what matters to you today has been forgotten. Do they remember you? Maybe, sort of, but they don’t care. They have abandoned your gods and your altars. Those few of your institutions that seem intact have in fact been hollowed out to house their new ethos. A handful of others may remain, vestigial and vaguely embarrassing. But boy howdy, line goes up.

Obviously, given our druthers, we’d all be the Assyrians: seize your opportunities, become great, but don’t lose your soul in the doing. But if it comes down to it — if, when the IPCC’s warning that “concatenated global impacts of extreme events continues to grow as the world’s economy becomes more interconnected” bears out, the Assyrian track isn’t an option — then I’d take the Greek way.

I don’t care whether, on the far side of our own Collapse, there’s still a thing we call “Congress” that makes things we call “laws”. Rome, after all, was theoretically ruled by the Senate for five hundred years of autocracy as all the meaning was leached from the retained forms of Republican governance. (Look, I’m sorry, you can call him your princeps and endow him with the powers of the consul, the tribune, the censor, and the pontifex maximus, but your emperor is still a king and the cursus honorum has no meaning when the army hands out the crown.) I don’t even really care if we still read Shakespeare or The Great Gatsby, although it would be more of a shame to lose those than the Constitution. But I do care that we value both order and liberty, however we structure our state to safeguard them. I care that we’re the sort of people who’d get Shakespeare and Fitzgerald if we had them around. Maybe we should start thinking about it before our Collapse, too.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: After 1177 B.C., by Eric H. Cline”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-07-08.

- “Transformation” is always a term worth taking with a pinch of salt because so often it’s a euphemism for “total civilizational collapse”. In the chapter on the Hittites, for example, Cline quotes one archaeologist to the effect that “[a] deep transformation took place in the former core of the empire around the capital Hattusa, resulting in a drastic decrease in political complexity, a shift to a subsistence household economy and a lack of evidence for any public institutions”. Relatedly, one of my children recently transformed a nice vase into a pile of broken glass.

In this case, though, Cline really does mean transformation.

September 10, 2025

QotD: “The [western Roman Empire] did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”

The fall of the Roman Empire in the West (please, right now, just mentally add the phrase “in the west” next to every “the fall of Rome” and similar phrase here and elsewhere) is complicated. I don’t mean it is complicated in its causes or effects (though it is that too), I mean it is complicated in its raw events: the who, what, where and when of it. Most students are taught a fairly simple version of this because most of what they need to actually learn is the cause and the effects and so the actual “fall” part is a sort of black box where Huns, Vandals, Goths, plague, climate and economic decline go in and political fragmentation, more economic decline and the European Middle Ages come out. The fall itself ends up feeling like an event rather than a process because it is compressed down to a single point, the black box where all of the causes become all of the effects. That is, frankly, a defensible way to teach the topic at a survey level (where it might get at most a lecture or two either at the end of a Roman History survey or the beginning of a Medieval History survey) and it is honestly more or less how I teach it.

But if you want to actually try to say something intelligent about the whole thing, you need to grapple with what actually happened, rather than the classroom black-box model designed for teaching efficiency rather than detail. We are … not going to do that today … though I will have some bibliography here for those who want to. The key thing here is that the “Fall of Rome” (in the West) is not an event, but a century long process from 376 to 476. Roman power (in the West) contracts for a lot of that, but it expands in periods as well, particularly under the leadership of Aetius (433-454) and Majorian (457-461); there are points where it would have really looked like the Romans might actually be able to recover. Even in 476 it was not obvious to anyone that Roman rule had actually ended; Odoacer, who had just deposed what was to be the last Roman emperor in the west promptly offered the crown to Zeno, the Roman emperor in the East (there is argument about his sincerity but James O’Donnell argues – very well, though I disagree on some key points – that this represented a real opportunity for Rome to rise from defeat in a new form yet again).

Glancing even further back historically, this wasn’t even the first time the Roman Empire had been on the brink of collapse. Beginning in 238, the Roman Empire had suffered a long series of crippling civil wars and succession crises collectively known as the Crisis of the Third Century (238-284). At one point, the empire was de facto split into three, with one emperor in Britain and Gaul, another in Italy, and the client kingdom of Palmyra essentially running the Eastern half of the empire under their queen Zenobia. Empires do not usually survive those kinds of catastrophes, but the Roman Empire survived the Crisis, recovered all of its territory (save Dacia) and even enjoyed a period of relative peace afterwards, before trouble started up again.

The reason that empires do not generally survive those kinds of catastrophes is that generally when empires weaken, they find that they contain all sorts of people who have been waiting, sometimes patiently, sometimes less so, for any opportunity to break away. The rather sudden collapse of the (Neo-)Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC) is a good case study. After having conquered much of the Near East, the Assyrians fell into a series of succession wars beginning in 627; their Mesopotamian subjects smelled blood and revolted in 625. That was almost under control by 620 when the Medes and Persians, external vassals of the Assyrians, smelled blood too and invaded, allying with the rebelling Babylonians in 616. Assyria was effectively gone by 612 with the loss and destruction of Ninevah; they had gone from the largest empire in the world at that time or at any point prior to non-existent in 15 years. While the Assyrian collapse is remarkable for its speed and finality, the overall process is much the same in most cases; once imperial power begins to wane, revolt suddenly looks more possible and so the downward slope of collapse can be very steep indeed (one might equally use the case study of decolonization after WWII as an example: each newly independent country increased the pressure on all of the rest).

Yet there is no great rush to the doors for Rome. Instead, as Guy Halsall puts it in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007), “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”. Among the kicked and gouged of course were Attila and his Huns. Fought to a draw at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, his empire disintegrated after his death two years later under pressure from both Germanic tribes and the Eastern Roman Empire (and the standard tendency for Steppe empires to fragment); of his three sons, Ellac was killed by revolting Germanic peoples who had been subject to the Huns, Dengizich by the (Eastern) Romans (we’re told his head was put on display in Constantinople) and the last, Ernak just disappears in our narrative after the death of Dengizich. The Romans, it turns out, did eventually get down to business to defeat the Huns. But the Romans doing all of that kicking, gouging and screaming were not the handful of old families from the early days of the Repulic; most of those hard-fighting Romans were people who in 14 AD would have been provincials. And indeed, the Roman Empire would survive, in the East, where Rome wasn’t, making for a Roman Empire that by 476 consisted effectively entirely of “provincial” Romans.

Instead what we see are essentially three sets of actions by provincial elites who in any other empire would have been leading the charge for the exits. There were the kickers, gougers and screamers, as Halsall notes. There were also, as Ralph Mathisen, Roman Aristocrats in Barbarian Gaul (1993) has noted, elites who – seeing the writing on the wall – made no effort to hasten the collapse of the empire but instead retreated into their estates, their books and their letters; these fellows often end up married into and advising the new “barbarian” kings who set up in the old Roman provinces (which in turn contributes quite a bit to the preservation and continued influence of Roman law and culture in the various fragmented successor states of the early Middle Ages). Finally, there were elites so confident that the empire would survive – because it always had! – that they mostly focused on improving their position within the empire, even at the cost of weakening it, not because they wanted out, but because “out” was inconceivable to them; both Halsall and also James O’Donnell, The Ruin of the Roman Empire (2009) document many of these. If I may continue my analogy, when the exit door was yawning wide open, almost no one walked through; some tried to put out the burning building they were in, others were content to be at the center of the ruins. But no one actually left.

During the Crisis of the Third Century, that set of responses had been crucial for the empire’s survival and for brief moments in the 400s, it looked like they might even have saved it again. For all of the things that brought the Roman Empire down, it is striking that “internal revolts” of long-ruled peoples weren’t one of them. And that speaks to the power of Rome’s effective (if, again, largely unintentional) management of diversity. The Roman willingness to incorporate conquered peoples into the core citizen body and into “Roman-ness” meant that even by 238 to the extent that the residents of the Empire could even imagine its collapse, they saw that potentiality as a disaster, rather than as a liberation. That gave the empire tremendous resiliency in the face of disaster, such that it took a century of unremitting bad luck to bring it down and even then, it only managed to take down half of it.

(As an aside, those provincial Romans were correct in the judgement that the collapse of the empire would mean disaster. The running argument about the fall of the Roman Empire is generally between the “decline and fall” perspective, which presents the collapse of the Roman Empire as a Bad Thing and the “change and continuity” perspective, which both stresses continuity after the collapse but also tends to try minimize the negative impacts of it, even to the point of suggesting that the average Roman peasant might have been better off in the absence of heavy Roman taxes. That latter view is particularly common among many medievalists, who are understandably quite tired of the unfairly poor reputation their period gets. This is an argument that for some time lived in the airy space of narrative and perspective where both sides could put an argument out. Unfortunately for some of the change-and-continuity arguments about living standards, archaeology has a tendency to give us data that is somewhat less malleable. That archaeological data shows, with a high degree of consistency, that while there is certainly some continuity between the Late Antique and the early Middle Ages the fall of Rome (in the West) killed lots of people (precipitous declines in population in societies without reliable birth control; probably this is mostly food scarcity, not direct warfare) and that living standards also declined to a degree that the results are archaeologically visible. As Brian Ward-Perkins notes in The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization (2005), the collapse causes cows to shrink, speaking to sudden scarcity of winter fodder (which in turn likely speaks to a general reduction in available nutrition). Some areas were worse hit than others; Robin Flemming, Britain After Rome (2010) notes, for instance, that in post-Roman Britain, pot-making technology was lost (because ceramic production had been focused in cities which had been largely depopulated out of existence). The fall of Rome might have been good for some people, but the evidence is, I think, at this point inescapable that it was quite bad for most people. Especially, one assumes, all of the people who got depopulated.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part V: Saving and Losing and Empire”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-07-30.

August 22, 2025

History’s Oldest Dessert – 4,000 Year Old Mersu

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 18 Mar 2025Short pastry filled with pistachios and dates

City/Region: Mari, Mesopotamia

Time Period: c. 1800 B.C.E.In the ancient ruined Mesopotamian city of Mari, a clay tablet receipt from 4,000 years ago was found that mentioned dates and pistachios for making mersu for the king. We don’t know exactly what mersu was or if there were other ingredients in it, but I think there was more to it than just dates and pistachios. The king employed eight specialists who made mersu, so my guess is that it was at least as complicated as this pastry, possibly much more so.

The flavor combination in this interpretation is wonderful. The pastry is a little crumbly, and the filling is chewy, rich, and quite sweet, with the added texture of the nuts.

I made my pastry dough unsweetened and I really liked the contrast between the unsweetened dough and the very sweet filling, but you can add some date syrup or honey to your dough if you’d like.

1 gur of dates

And 10 sila of pistachios

For making mersu

Meal of the king

— Receipt from Mari, c. 1800 BCE

August 7, 2025

QotD: The lost-then-found-again Hittite civilization

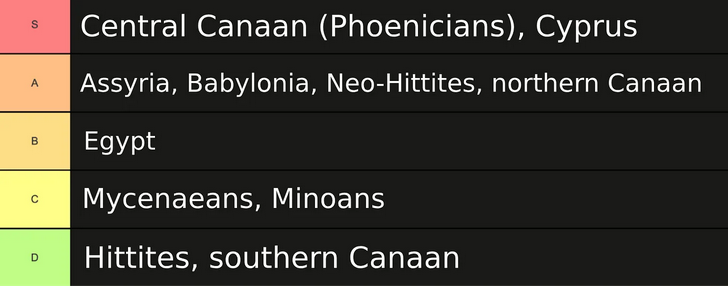

… Mycenaean Greece was as much an outlier as sub-Roman Britain: the civilizational collapse in the Aegean was unusually prolonged and severe compared to the fates of many of the other peoples of the Late Bronze Age. Here I have helpfully reformatted Cline’s chart of how resilient the various societies proved:

Let’s take a brief tour through the various fates of these societies. I’ll come back to the Phoenicians at the end, because their example raises interesting questions when considered in contrast with the Mycenaeans. For the moment, though, let’s begin like civilization itself: in Mesopotamia.

Before the Late Bronze Age Collapse, the Assyrian and Babylonian empires had numbered among the Great Powers of the age: linked by marriage, politics, war, and trade to the other mighty kings, they spent much of their time conducting high-level diplomacy and warfare. As far as we can tell, they did well in the initial collapse: there’s a brief hiatus in Assyrian royal inscriptions running from about 1208 to 1132 BC, but records resume again with the reign of Aššur-reša-iši I and his repeated battles with his neighbor to the south, the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I (no relation). But although the kings of the late twelfth century continued much as their Bronze Age predecessors had — waging war, building palaces, going hunting, accepting tribute, collecting taxes, and ordering it all recorded in stone and clay — the world had changed around them. No longer were there huge royal gifts sent to and from fellow great kings, “My Majesty’s brother”1 overseas; now their diplomatic world consisted of tiny petty kings of nearby cities who could be looted or extorted at will.

Mesopotamia didn’t escape unscathed forever: beginning around 1080 BC, texts begin to record severe droughts, invading Aramaeans, and total crop failures. There was a major drought in 1060 BC, and then both the Assyrian and Babylonian records record further drought every ten years like clockwork — sometimes accompanied by plague, sometimes by “troubles and disorder” — until the end of the eleventh century BC. Most of the tenth century was equally dire, with chronicles recording grain shortages, invasions, and a cessation of regular offerings to the gods.

But unlike the Mycenaeans, and in spite of real suffering (ancient Babylonia is estimated to have lost up to 75% of its population in the three hundred years after the Collapse), both Mesopotamian empires were able to hang on to civilization. There were still kings, there were still scribes, and there were still boundary stones on which to record things like “distress and famine under King Kaššu-nadin-ahhe”. And when conditions finally improved, Assyria and Babylonia were both able to bounce back. When at last the Assyrian recovery began under Aššur-dan II (934-912 BC), for example, he (or more realistically, his scribe) was able to write: “I brought back the exhausted people of Assyria who had abandoned their cities and houses in the face of want, hunger, and famine, and had gone up to other lands. I settled them in cities and homes which were suitable and they dwelt in peace”. Clearly, Assyria still retained enough statehood to effect the sort of mass population transfer that had long been a feature of Mesopotamian polities.2

Over the next few centuries, the Neo-Assyrian Empire would come to dominate the Near East, regularly warring with (and eventually conquering) Babylon and collecting tribute from smaller states all over the region. At its peak, it was the largest empire history had ever known, covering a geographic extent unsurpassed until the Achaemenids. The Babylonians had to wait a little longer for their moment in the sun, but near the end of the seventh century they overthrew their Assyrian overlords and ushered in the Neo-Babylonian Empire. (Less than a century later, Cyrus showed up.)

So how did Babylon and Assyria hold on to civilization — statehood, literacy, monumental architecture, and so forth — when the Greeks lost it and had to rebuild almost from scratch? Unfortunately, Cline doesn’t really answer this. He offers extensive descriptions of all the historical and archaeological evidence for the diverse fates of various Late Bronze Age societies, but only at the very end of the book does he briefly run through the theories (and even then it’s pretty lackluster). He does have a suggestion about the timing — the ninth century Assyrian resurgence lines up almost perfectly with the abnormally wet conditions during the Assyrian megapluvial — but why was it the Assyrians who found themselves particularly well-positioned to take advantage of the shift in the climate? Why not, say, the Hittites?

Sometime around 1225 BC, the Hittite king Tudhaliya IV wrote to his brother-in-law and vassal, Shaushgamuwa of Amurru, that only the rulers of Egypt, Babylonia, and Assyria were “Kings who are my equals in rank”.3 A mere thirty years later, though, his capital city of Hattusa would lie abandoned and destroyed. Modern excavators describe ruins reduced to “ash, charred wood, mudbricks and slag formed when mud-bricks melted from the intense heat of the conflagration”.

And with that, the Hittites essentially vanished from history.

They were so thoroughly forgotten, in fact, that when nineteenth-century archaeologists discovered the ruins of their civilization in Anatolia, they had no idea who these people were. (Eventually they identified the new sites with the Hittites of the Bible, who lived hundreds of years later and hundreds of miles to the south, out of sheer ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.)4

What happened to the Hittites? Well, Cline suggests the usual mélange of drought, famine, and interruption of international trade routes, as well as a potential usurpation attempt from Tudhaliya’s cousin Kurunta, but the actual answer is that we’re not sure. Given the timing, they may have been the first of the Late Bronze Age dominos to fall; given the lack of major rivers in central Anatolia, they may have been uniquely susceptible to drought. Hattusa may have been abandoned before the fire — its palaces and temples show little sign of looting, suggesting they [may] already have been emptied out — but many other sites in the Hittites’ central Anatolian heartland were destroyed around the same time, and some of those have bodies in the destruction layer. But whatever the order of events, Hittite civilization collapsed as thoroughly and dramatically as the Mycenaeans’ had done, and with a similar pattern of depopulation and squatters in the ruins. Unlike the Mycenaeans, though, the Hittites would never be followed by successors who inherited their culture; the next civilization of Anatolia was the Phrygians, who probably arrived from Europe in the vacuum following the Hittites’ fall.

There was one exception: in the Late Bronze Age, cadet branches of the Hittite royal family had ruled a few small satellite statelets in what is now northern Syria, and many of these “Neo-Hittite” polities managed to survive the Collapse. A tiny, far-flung corner of a much greater civilization, they nevertheless outlasted the destruction of their metropole and maintained Hittite-style architecture and hieroglyphic inscriptions well into the Iron Age.5 (They would be swallowed up by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the late eighth century BC.) And though the Neo-Hittite kings ruled over tiny rump states, we’re now able to translate inscriptions in which they referred themselves by the same titles the Bronze Age Hittite “Great Kings” had employed. The records of their larger neighbors, which had a much greater historical impact, seem to have followed suit: the Neo-Hittites in Syria probably actually were the Hittites of the Bible! Chalk up another one for nineteenth century archaeology.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: After 1177 B.C., by Eric H. Cline”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-07-08.

1. I really think we should bring back monarchs referring to themselves as “my Majesty”. So much cooler than the royal “we”. Or combine them: “our Majesty”!

2. The Babylonian Captivity, much later in the Iron Age, was far from historically unique.

3. The list actually reads, “the King of Egypt, the King of Babylonia, the King of Assyria,

and the King of Ahhiyawa” — the strikethrough appears in the original clay tablet! A generation earlier, under Tudhaliya’s father Hattusili III, the Hittite texts had consistently referred to the king of Ahhiyawa as a “great King” and a “brother”, but apparently the geostrategic position of the Mycenaean ruler had degraded substantially.4. We now know that the Hittites spoke an Indo-European language and referred to themselves “Neshites”, but the name has stuck.

5. I went looking for a good historical analogy for the Neo-Hittite kingdoms and discovered, to my delight, the Kingdom of Soissons, which preserved Romanitas for a few decades after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Neo-Hittites lasted a lot longer.

July 22, 2025

Battle for Gaza 1917: The Palestinian Campaign of WW1

The Great War

Published 14 Feb 2025The ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict has its roots in another war more than a century ago. When the First World War began in 1914, the territory of today’s Israel and Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. But in 1917 the British Empire began a campaign that would change history: there would be bitter fighting in Gaza, wild cavalry charges, even talk of a modern crusade. And it would lay the foundations for a century of violence.

(more…)

April 7, 2025

QotD: The new Neolithic agrarian villages allowed for the development of the parasitic state

… despite all these drawbacks, people whose distant ancestors had enjoyed the wetland mosaic of subsistence strategies were now living in the far more labor-intensive, precarious confines of the Neolithic village, where one blighted crop could spell disaster. And when disaster struck, as it often did, the survivors could melt back into the world of their foraging neighbors, but slow population growth over several millennia meant that those diverse niches were full to the bursting, so as long as more food could be extracted at a greater labor cost, many people had incentive to do so.

And just as this way of life — [Against the Grain author James C.] Scott calls it the “Neolithic agro-complex”, but it’s really just another bundle of social and physical technologies — inadvertently created niches for the weeds that thrive in recently-tilled fields1 and the fleas that live on our commensal vermin, it also created a niche for the state. The Neolithic village’s unprecedented concentration of manpower, arable land, and especially grain made the state possible. Not that the state was necessary, mind you — the southern Mesopotamian alluvium had thousands of years of sedentary agriculturalists living in close proximity to one another before there was anything resembling a state — but Scott writes that there was “no such thing as a state that did not rest on an alluvial, grain-farming population”. This was true in the Fertile Crescent, it was true along the Nile, it was true in the Indus Valley, and it was true in the loess soils of “Yellow” China.2 And Scott argues that it’s all down to grain, because he sees taxation at the core of state-making and grain is uniquely well-suited to being taxed.

Unlike cassava, potatoes, and other tubers, grain is visible: you can’t hide a wheatfield from the taxman. Unlike chickpeas, lentils, and other legumes, grain all ripens at once: you can’t pick some of it early and hide or eat it before the taxman shows up. Moreover, unhusked grain stores particularly well, can be divided almost infinitely for accounting purposes (half a cup of wheat is a stable and reliable store of value, while a quarter of a potato will rot), and has a high enough value per unit volume that it’s economically worthwhile to transport it long distances. All this means that sedentary grain farmers become taxable in a way that hunter-gatherers, nomadic pastoralists, swiddeners, and other “nongrain peoples” are not, because you know exactly where to find them and exactly when they can be expected to have anything worth taking. And then, of course, you’ll want to build some walls to protect your valuable grain-growing subjects from other people taking their grain (and also, perhaps, to keep them from running for the hills), and you’ll want systems of measurement and record-keeping so you know how much you can expect to get from each of them, and pretty soon, hey presto! you have something that looks an awful lot like civilization.

The thing is, though, that Scott doesn’t think this is an improvement. It certainly wasn’t an improvement for the new state’s subjects, who were now forced into backbreaking labor to produce a grain surplus in excess of their own needs (and prevented from leaving their work), and it wasn’t an improvement for the non-state (or, later, other-state) peoples who were constantly being conquered and relocated into the state’s core territory as new domesticated subjects to be worked just like its domesticated animals. In fact, he goes so far as to suggest that our archaeological records of “collapse” — the abandonment and/or destruction of the monumental state center, usually accompanied by the disappearance of elites, literacy, large-scale trade, and specialist craft production — in fact often represent an increase in general human well-being: everyone but the court elite was better off outside the state. “Collapse”, he argues, is simply “the disaggregation of a complex, fragile, and typically oppressive state into smaller, decentralized fragments”. Now, this may well have been true of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium in 3000 BC, where every statelet was surrounded by non-state, non-grain peoples hunting and fishing and planting and herding, but it’s certainly not true of a sufficiently “domesticated” people. Were the oppida Celts, with their riverine trading networks, better off than their heavily urbanized Romano-British descendants? Well, the Romano-Britons had running water and heated floors and nice pottery to eat off of and Falernian wine to drink, but there’s certainly a case to be made that these don’t make up for lost freedoms. But compare them with the notably shorter and notably fewer involuntarily-rusticated inhabitants of sub-Roman Britain a few hundred years later and even if you don’t think running water is worth much (you’re wrong), you have to concede that the population nosedive itself suggests that there is real human suffering involved in the “collapse” of a sufficiently widespread civilization.3

But even this is begging the question. We can argue about the relative well-being of ordinary people in various sorts of political situations, and it’s a legitimately interesting topic, both in what data we should look at — hunter-gatherers really do work dramatically less than agriculturalists4 — and in debating its meaning.5 And Scott’s final chapter, “The Golden Age of the Barbarians”, makes a pretty convincing case that they were materially better off than their state counterparts, especially once the states really got going and the barbarians could trade with or raid them to get the best of both worlds! But however we come down on all these issues, we’re still assuming that the well-being of ordinary people — their freedom from labor and oppression, their physical good health — is the primary measure of a social order. And obviously it ain’t nothing — salus populi suprema lex and so forth — but man does not live by

breada mosaic of non-grain foodstuffs alone. There are a lot of important things that don’t show up in your skeleton! We like civilization not because it produces storehouses full of grain and clay tablets full of tax records, but because it produces art and literature and philosophy and all the other products of our immortal longings. And, sure, this was largely enabled by taxes, corvée labor, conscription, and various forms of slavery, but on the other hand we have the epic of Gilgamesh.6 And obviously you don’t get art without civilization, which is to say the state. Right?Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: Against the Grain, by James C. Scott”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-08-21.

1. Oats apparently began as one of them!

2. It was probably also true in Mesoamerica and the Andes, where maize was the grain in question, but Scott doesn’t get into that.

3. No, the population drop cannot be explained by all the romanes eunt domus.

4. That famous “twenty hours a week” number you may have heard is bunk, but it’s really only about forty, and that includes all the housekeeping, food preparation, and so forth that we do outside our forty-hour workweeks.

5. For example, does a thatched roof in place of ceramic tiles represent #decline, or is it a sensible adaptation to more local economy? Or take pottery, which is Bryan Ward-Perkins’s favorite example in his excellent case that no really, Rome actually did fall: a switch in the archaeological record from high-quality imported ceramics to rough earthenwares made from shoddy local clays is definitely a sign of societal simplification, but it isn’t prima facie obvious that a person who uses the product of an essentially industrial, standardized process is “better off” than someone who makes their own friable, chaff-tempered dishes.

6. Or food rent and, uh, all of Anglo-Saxon literature, whatever.

January 11, 2025

QotD: “Composite” pre-gunpowder infantry units

I should be clear I am making this term up (at least as far as I know) to make a contrast between what Total War has, which are single units made up of soldiers with identical equipment loadouts that have a dual function (hybrid infantry) and what it doesn’t have: units composed of two or more different kinds of infantry working in concert as part of a single unit, which I am going to call composite infantry.

This is actually a very old concept. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC) is one of the earliest states where we have pretty good evidence for how their infantry functioned – there was of course infantry earlier than this, but Bronze Age royal records from Egypt, Mesopotamia or Anatolia tend to focus on the role of elites who, by the late Bronze Age, are increasingly on chariots. But for the early Iron Age Neo-Assyrian empire, the fearsome effectiveness of its regular (probably professional) infantry, especially in sieges, was a key component of its foreign-policy-by-intimidation strategy, so we see a lot more of them.

That infantry was split between archers and spear-and-shield troops, called alternately spearmen (nas asmare) or shield-bearers (sab ariti). In Assyrian artwork, they are almost always shown in matched pairs, each spearman paired off with a single archer, physically shielding the archer from attack while the archer shoots. The spearmen are shown with one-handed thrusting spears (of a fairly typical design: iron blade, around 7 feet long) and a shield, either a smaller round shield or a larger “tower” shield. Assyrian records, meanwhile, reinforce the sense that these troops were paired off, since the number of archers and spearmen typically match perfectly (although the spearmen might have subtypes, particularly the “Qurreans” who may have been a specialist type of spearman recruited from a particular ethnic group; where the Qurreans show up, if you add Qurrean spearmen to Assyrian spearmen, you get the number of archers). From the artwork, these troops seem to have generally worked together, probably lined up in lines (in some cases perhaps several pairs deep).

The tactical value of this kind of composite formation is obvious: the archers can develop fire, while the spearmen provide moving cover (in the form of their shields) and protection against sudden enemy attack by chariot or cavalry with their spears. The formation could also engage in shock combat when necessary; the archers were at least sometimes armored and carried swords for use in close combat and of course could benefit (at least initially) from the shields of the front rank of spearmen.

The result was self-shielding shock-capable foot archer formations. Total War: Warhammer also flirts with this idea with foot archers who have their own shields, but often simply adopts the nonsense solution of having those archers carry their shields on their backs and still gain the benefit of their protection when firing, which is not how shields work (somewhat better are the handful of units that use their shields as a firing rest for crossbows, akin to a medieval pavisse).

We see a more complex version of this kind of composite infantry organization in the armies of the Warring States (476-221 BC) and Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) periods in China. Chinese infantry in this period used a mix of weapons, chiefly swords (used with shields), crossbows and a polearm, the ji which had both a long spearpoint but also a hook and a striking blade. In Total War: Three Kingdoms, which represents the late Han military, these troop-types are represented in distinct units: you have a regiment of ji-polearm armed troops, or a regiment of sword-and-shield troops, or a regiment of crossbowmen, which maneuver separately. So you can have a block of polearms or a block of crossbowmen, but you cannot have a mixed formation of both.

Except that there is a significant amount of evidence suggesting that this is exactly how the armies of the Han Dynasty used these troops! What seems to have been common is that infantry were organized into five-man squads with different weapon-types, which would shift their position based on the enemy’s proximity. So against a cavalry or chariot charge, the ji might take the front rank with heavier crossbows in support, while the sword-armed infantry moved to the back (getting them out of the way of the crossbows while still providing mass to the formation). Of course against infantry or arrow attack, the swordsmen might be moved forward, or the crossbowmen or so on (sometimes there were also spearmen or archers in these squads as well). These squads could then be lined up next to each other to make a larger infantry formation, presenting a solid line to the enemy.

(For more on both of these military systems – as well as more specialist bibliography on them – see Lee, Waging War (2016), 89-99, 137-141.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

January 1, 2025

3,500 Years of Hangover Cures – Kishkiyya from Baghdad

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 31 Dec 2024A slightly sour lamb stew with herbs, chickpeas, and fat, eaten as a hangover cure in 10th century Baghdad

City/Region: Baghdad

Time Period: 10th CenturyWhere there are hangovers, there are hangover cures. Throughout history they’ve varied from having a good wash, drinking lemonade while drinking alcohol, and the dubious prairie oyster. This stew is kind of like 10th century Baghdad’s version of my favorite hangover food: a greasy burger and fries.

Fatty lamb is stewed with kishka (a dried yogurt-like dairy product), verjuice, chickpeas, herbs, and greens, along with some olive oil just to make sure there’s enough grease involved. It doesn’t look all that pretty, but it tastes good. It’s complex and layered, with each flavor following the last, and the variety of textures is wonderful.

Wash 3 ratls meat and put it in a pot. Add ½ ratl chopped onion, ¼ ratl fresh herbs, a handful of chickpeas, 1 piece galangal, and ¼ ratl olive oil. Pour water to submerge the ingredients in the pot. Let the pot cook until meat is almost done. Add any of the seasonal green vegetables and a little chard. When everything in the pot is cooked, add 3 pieces of sour kishk, and ½ ratl kishk of Albu-Sahar, Mawsili, or Bahaki. Pound them into fine powder and dissolve them in 1 ratl (2 cups) ma’hisrim (juice of unripe sour grapes).

When kishk is done, add 2 dirhams (6 grams) cumin and an equal amount of cassia. Add a handful of finely chopped onion. Do not stir the pot. When the onion cooks and falls apart, add to the pot 2 danaqs (1 gram) cloves and a similar amount of spikenard.

Stop fueling the fire, let the pot simmer and rest on the remaining heat then take it down, God willing.

— Kitāb al-Tabīkh by ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq, 10th Century, translation from Annals of the Caliph’s Kitchen by Nawal Nasrallah

December 13, 2024

The influence of Mesopotamian cultures on ancient Greece

James Pew and Scott Miller begin their series on the history of western education by looking at the way Greek civilization was influenced by the Mesopotamian cultures who used cuneiform writing for three thousand years:

An example of a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform text (in this case, a portion of the Epic of Gilgamesh)

In the 19th century, three new discoveries began to militate against “the image of pure, self-contained Hellenism”. They were: “the reemergence of the ancient Near East and Egypt through the decipherment of cuneiform and hieroglyphic writing, the unearthing of Mycenaean civilization, and the recognition of an Orientalizing phase in the development of archaic Greek art”.

To sketch the significance of just one of these discoveries, what the discovery of cuneiform writing means for the history of writing and literature, we have with cuneiform not only the first writing system in human history, but also the longest running (it was in use for over 3,000 years); cuneiform texts are, at the same time, the best preserved and most numerous textual records from the ancient world by far (there are hundreds of thousands of cuneiform documents in museum archives today because the signs were inscribed on clay tablets which preserve better across time than other materials used for writing in ancient times). This complex writing system, consisting of thousands of signs, was developed first in Mesopotamia by the Sumerians and, subsequently, it was adopted by the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians in the same area. It emerged c. 3200 B.C. as a response to social and economic complexities generated by the world’s first cities: invariably, the impetus to create a writing system comes down to the need to document and track the transfer of food stuffs, material goods, temple offerings, and so forth, the administration of complex urban society. On the other hand, written literature in the form of myth, poetry and the like, are secondary developments that may follow a long time later (if at all). In centuries to follow, Mesopotamian scribes would begin to write down epic tales telling the exploits of heroic kings, such as Gilgamesh, along with hymns and prayers to the Mesopotamia gods, incantations to ward off demons and diseases, texts containing lists of known phenomena, proverbs, reports of astrological phenomena and their omens, medical and magical texts to be used by the healing expert, and many text types besides.

On the Question of Greek Borrowing from the more ancient East: This series will delve into the work of many of these cutting-edge historical scholars who follow the evidence from Orient to Occident. Academic’s like Albin Lesky, M.L. West, Walter Burkert, Margalit Finkelberg, Harald Haarmann, Daniel Ogden, Mark Griffith, and more.

It is no easy task to establish links between Greece and ancient Near Eastern civilizations, and the difficulty has to do with more than vast expanses of time and space. Typically, modern scholars of classical Greece have a tendency to “transform ‘oriental’ and ‘occidental’ into a polarity, implying antithesis and conflict”. According to Burkert, it was not until the Greeks fought back the Persian Empire that they became aware of their distinct identity (as separate from the orient). In addition, it was not until many years later, during the crusades, that “the concept and the term ‘Orient’ actually enter(ed) the languages of the West”. The reluctance on the part of many scholars to accept a universal conception of cultural development which involved “borrowing”, “loan words”, and “cultural diffusion” amongst the different ancient peoples living in both the Near East and the Aegean regions, is due to intellectual currents that first took shape in Germany over two centuries ago. In Burkert’s words, “Increasing specialization of scholarship converged with ideological protectionism, and both constructed an image of a pure, classical Greece in splendid isolation”.

It was essentially a trio of academic fads that “erected their own boundaries and collectively fractured the Orient-Greece axis”. The first was the breaking apart of theology and philology. Until well into the 18th century, “the Hebrew Bible naturally stood next to the Greek classics, and the existence of cross-connections did not present any problems”. The second was the rise of the ideology of Romantic Nationalism, “which held literature and spiritual culture to be intimately connected with an individual people, tribe, or race. Origins and organic development rather than reciprocal cultural influences became the key to understanding”. And the third was the discovery by linguistic scholars of “Indo-European”, the “common archetype” of most European languages (as well as Persian and Sanskrit).

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff offered a “scornful assessment” indicative of the faddish and far more isolated conception of ancient Greece in 1884: “the peoples and states of the Semites and the Egyptians which had been decaying for centuries and which, in spite of the antiquity of their culture, were unable to contribute anything to the Hellenes [the Greeks] other than a few manual skills, costumes, and implements of bad taste, antiquated ornaments, repulsive fetishes for even more repulsive fake divinities …” A common take at the time which would later prove to be quite incomplete. It should be noted that Romantic Nationalism, coupled with the discovery of Indo-European (which demonstrates no link between European and Semitic languages) seems to have contributed to what gave “anti-Semitism a chance”. Tragically, it was at the point when the Jews were finally being granted full legal equality in Europe when national-romantic consciousness and the rejection of orientalism helped set the stage for the escalation in Jewish persecution that eventually led to the horror of horrors: the Holocaust.

The Mesopotamians would never, as the later Greeks did c. 600 B.C., formulate an abstract concept of “nature” and analyze phenomena as having a natural developmental explanation rather than the traditional explanation (that being, e.g. the gods made it so). Thus, they would never develop philosophy or science as we think of it, and so there are certain categories of analysis and knowledge that are uniquely Greek in the ancient world. However, as the innovators of a form of agrarian society that was productive and sophisticated enough to sustain the world’s first cities, Mesopotamians needed to be able to examine and quantify time (in order to know when to plant) and so they developed the lunar calendar of 12 months, they developed the 12 double-hour day, they gave names to the observable planets and charted the night sky into constellations; They needed to be able to measure physical space and allot pieces of land to land owners, and so they created the world’s earliest form of basic geometry. The types of knowledge just named are the types of knowledge that scholars believe would have been of interest to the Greeks, and, indeed, many suspect that iron age Greeks borrowed these insights from the Babylonians. Whether the Greek story of Heracles could have been influenced by Mesopotamian hero epics such as the Epic of Gilgamesh is a more contentious — though intriguing — topic.

So, how did Greece find itself in a position to receive the baton of civilization and even to carry it further forward? Because of the great work of modern scholars, we know that an informal but early (proto) archetypal version of education (not yet organized education) begins in the Mediterranean, in archaic Greece, before the classical period. Even before this, although it is not exactly clear as to the extent, it has been determined that Bronze Age Greek cultures located around the area of the Aegean sea (also known as Aegean Civilization) – the Mycenaean on mainland Greece, the Minoan on the island of Crete and the Cyclades (also known as the Aegean Islands) – were not only in contact with each other, but also with neighboring civilizations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the Levant.

October 4, 2024

QotD: Farmers and slaves in ancient Mesopotamia

In one of my favorite parts of the book [Against The Grain], Scott discusses how this shaped the character of early Near Eastern warfare. Read a typical Near Eastern victory stele, and it looks something like “Hail the glorious king Eksamplu, who campaigned against Examplestan and took 10,000 prisoners of war back to the capital”. Territorial conquest, if it happened at all, was an afterthought; what these kings really wanted was prisoners. Why? Because they didn’t even have enough subjects to farm the land they had; they were short of labor. Prisoners of war would be resettled on some arable land, given one or another legal status that basically equated to slave laborers, and so end up little different from the native-born population. The most extreme example was the massive deportation campaigns of Assyria (eg the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel), but everybody did it because everybody knew their current subjects were a time-limited resources, available only until they gradually drained out into the wilderness.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Against The Grain“, Slate Star Codex, 2019-10-15.

September 12, 2024

QotD: The collapse of early civilizations in Mesopotamia

Early states were pretty time-limited themselves. [In Against The Grain,] Scott addresses the collapse of early civilizations, which was ubiquitous; typical history disguises this by talking about “dynasties” or “periods” rather than “the couple of generations an early state could hold itself together without collapsing”.

Robert Adams, whose knowledge of the early Mesopotamian states is unsurpassed, expresses some astonishment at the Third Dynasty of Ur (Ur III), in which five kings succeeded one another over a hundred-year period. Though it too collapsed afterward, it represented something of a record of stability.

Scott thinks of these collapses not as disasters or mysteries but as the expected order of things. It is a minor miracle that some guy in a palace can get everyone to stay on his fields and work for him and pay him taxes, and no surprise when this situation stops holding. These collapses rarely involved great loss of life. They could just be a simple transition from “a bunch of farming towns pay taxes to the state center” to “a bunch of farming towns are no longer paying taxes to the state center”. The great world cultures of the time – Egypt, Sumeria, China, whereever – kept chugging along whether or not there was a king in the middle collecting taxes from them. Scott warns against the bias of archaeologists who – deprived of the great monuments and libraries of cuneiform tablets that only a powerful king could produce – curse the resulting interregnum as a dark age or disaster. Probably most people were better off during these times.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Against The Grain“, Slate Star Codex, 2019-10-15.

August 17, 2024

QotD: Sheep and wool in the ancient and medieval world

Our second fiber, wool, as readers may already be aware, comes from sheep (although goat and horse-hair were used rarely for some applications; we’re going to stick to sheep’s wool here). The coat of a sheep (its fleece) has three kinds of fibers in it: wool, kemp and medullated fibers. Kemp fibers are fairly weak and brittle and won’t accept dye and so are generally undesirable, although some amount of kemp may end up in wool yarn. Likewise, medullated fibers are essentially hair (rather than wool) and lack elasticity. But the wool itself, composed mostly of the protein keratin along with some lipids, is crimped (meaning the fibers are not straight but very bendy, which is very valuable for making fine yarns) and it is also elastic. There are reasons for certain applications to want to leave some of the kemp in a wool yarn that we’ll get to later, but for the most part it is the actual wool fibers that are desirable.

Sheep themselves probably descend from the wild mouflon (Ovis orientalis) native to a belt of uplands bending over the northern edge of the fertile crescent from eastern Turkey through Armenia and Azerbaijan to Iran. The fleeces of these early sheep would have been mostly hair and kemp rather than wool, but by the 4th millennium BC (as early as c. 3700 BC), we see substantial evidence that selective breeding for more wool and thicker coats has begun to produce sheep as we know them. Domestication of course will have taken place quite a bit earlier (selective breeding is slow to produce such changes), perhaps around 10,000 BC in Mesopotamia, spreading to the Indus river valley by 7,000 BC and to southern France by 6,000 BC, while the replacement of many hair breeds of sheep with woolly sheep selectively bred for wool production in Northern Mesopotamia dates to the third century BC.1 That process of selective breeding has produced a wide variety of local breeds of sheep, which can vary based on the sort of wool they produce, but also fitness for local topography and conditions.

As we’ve already seen in our discussion on Steppe logistics, sheep are incredibly useful animals to raise as a herd of sheep can produce meat, milk, wool, hides and (in places where trees are scarce) dung for fuel. They also only require grass to survive and reproduce quickly; sheep gestate for just five months and then reach sexual maturity in just six months, allowing herds of sheep to reproduce to fill a pasture quickly, which is important especially if the intent is not merely to raise the sheep for wool but also for meat and hides. Since we’ve already been over the role that sheep fill in a nomadic, Eurasian context, I am instead going to focus on how sheep are raised in the agrarian context.

While it is possible to raise sheep via ranching (that is, by keeping them on a very large farm with enough pastureland to support them in that one expansive location) and indeed sheep are raised this way today (mostly in the Americas), this isn’t the dominant model for raising sheep in the pre-modern world or even in the modern world. Pre-modern societies generally operated under conditions where good farmland was scarce, so flat expanses of fertile land were likely to already be in use for traditional agriculture and thus unavailable for expansive ranching (though there does seem to be some exception to this in Britain in the late 1300s after the Black Death; the sudden increase in the cost of labor – due to so many of the laborers dying – seems to have incentivized turning farmland over to pasture since raising sheep was more labor efficient even if it was less land efficient and there was suddenly a shortage of labor and a surplus of land). Instead, for reasons we’ve already discussed, pastoralism tends to get pushed out of the best farmland and the areas nearest to towns by more intensive uses of the land like agriculture and horticulture, leaving most of the raising and herding of sheep to be done in the rougher more marginal lands, often in upland regions too rugged for farming but with enough grass to grow. The most common subsistence strategy for using this land is called transhumance.

Transhumant pastoralists are not “true” nomads; they maintain permanent dwellings. However, as the seasons change, the transhumant pastoralists will herd their flocks seasonally between different fixed pastures (typically a summer pasture and a winter pasture). Transhumance can be either vertical (going up or down hills or mountains) or horizontal (pastures at the same altitude are shifted between, to avoid exhausting the grass and sometimes to bring the herds closer to key markets at the appropriate time). In the settled, agrarian zone, vertical transhumance seems to be the most common by far, so that’s what we’re going to focus on, though much of what we’re going to talk about here is also applicable to systems of horizontal transhumance. This strategy could be practiced both over relatively short distances (often with relatively smaller flocks) and over large areas with significant transits (see the maps in this section; often very significant transits) between pastures; my impression is that the latter tends to also involve larger flocks and more workers in the operation. It generally seems to be the case that wool production tended towards the larger scale transhumance. The great advantage of this system is that it allows for disparate marginal (for agriculture) lands to be productively used to raise livestock.

This pattern of transhumant pastoralism has been dominant for a long time – long enough to leave permanent imprints on language. For instance, the Alps got that name from the Old High German alpa, alba meaning which indicated a mountain pasturage. And I should note that the success of this model of pastoralism is clearly conveyed by its durability; transhumant pastoralism is still practiced all over the world today, often in much the same way as it was centuries or millennia ago, with a dash of modern technology to make it a bit easier. That thought may seem strange to many Americans (for whom transhumance tends to seem very odd) but probably much less strange to readers almost anywhere else (including Europe) who may well have observed the continuing cycles of transhumant pastoralism (now often accomplished by moving the flocks by rail or truck rather than on the hoof) in their own countries.

For these pastoralists, home is a permanent dwelling, typically in a village in the valley or low-land area at the foot of the higher ground. That low-land will generally be where the winter pastures are. During the summer season, some of the shepherds – it does not generally require all of them as herds can be moved and watched with relatively few people – will drive the flocks of sheep up to the higher pastures, while the bulk of the population remains in the village below. This process of moving the sheep (or any livestock) over fairly long distances is called droving and such livestock is said to be moved “on the hoof” (assuming it isn’t, as in the modern world, transported by truck or rail). Sheep are fairly docile animals which herd together naturally and so a skilled drover can keep large flock of sheep together on their own, sometimes with the assistance of dogs bred and trained for the purpose, but just as frequently not. While cattle droving, especially in the United States, is often done from horseback, sheep and goats are generally moved with the drovers on foot.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Clothing, How Did They Make It? Part I: High Fiber”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-03-05.

1. On this, note E. Vila and D. Helmer, “The Expansion of Sheep Herding and the Development of Wool Production in the Ancient Near East” in Wool Economy in the Ancient Near East and the Aegean, eds. C. Breniquet and C. Michel (2014), which has the archaeozoological data).

April 15, 2024

QotD: Cereal cultivation also helped grow the centralized state

Sumer just before the dawn of civilization was in many ways an idyllic place. Forget your vision of stark Middle Eastern deserts; in the Paleolithic the area where the first cities would one day arise was a great swamp. Foragers roamed the landscape, eating everything from fishes to gazelles to shellfish to wild plants. There was more than enough for everyone; “as Jack Harlan famously showed, one could gather enough [wild] grain with a flint sickle in three weeks to feed a family for a year”. Foragers alternated short periods of frenetic activity (eg catching as many gazelles as possible during their weeklong migration through the area) with longer periods of rest and recreation.

Intensive cereal cultivation is miserable work requiring constant toil with little guarantee of a good harvest. Why would anyone leave this wilderness Eden for a 100% wheat diet?

Not because they were tired of wandering around; Scott presents evidence that permanent settlements began as early as 6000 BC, long before Uruk, the first true city-state, began in 3300. Sometimes these towns subsisted off of particularly rich local wildlife; other times they practiced some transitional form of agriculture, which also antedated states by millennia. Settled peoples would eat whatever plants they liked, then scatter the seeds in particularly promising-looking soil close to camp – reaping the benefits of agriculture without the back-breaking work.

And not because they needed to store food. Hunter-gatherers could store food just fine, from salting animal meat to burying fish and letting it ferment to just having grain in siloes like everyone else. There is ample archaeological evidence of all of these techniques. Also, when you are surrounded by so much bounty, storing things takes on secondary importance.

And not because the new lifestyle made this happy life even happier. While hunter-gatherers enjoyed a stable and varied diet, agriculturalists subsisted almost entirely on grain; their bones display signs of significant nutritional deficiency. While hunter-gatherers were well-fed, agriculturalists were famished; their skeletons were several inches shorter than contemporaneous foragers. While hunter-gatherers worked ten to twenty hour weeks, agriculturalists lived lives of backbreaking labor. While hunter-gatherers who survived childhood usually lived to old age, agriculturalists suffered from disease, warfare, and conscription into dangerous forced labor.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Against The Grain“, Slate Star Codex, 2019-10-15.