I joked on Coronation Day that the only people not trying to have a good experience there were the British republicans, but they did get a bit more attention due to their proximity to the Royal Procession than they normally manage:

I mentioned before that it was a happy crowd, with high spirits. The crowd didn’t strike me as remarkable, which is to say, there wasn’t anything particularly notable about it. It was mixed. You’d find every age group and colour there, as well as a smattering of obvious tourists. Lots of people had little Union Jacks they would wave or tuck into the brims of hats or under backpack straps. Some wore full-sized flags as capes. A few young men, who’d obviously been drinking either since early that morning or perhaps the night before, were there in cheap royalty costumes — robes and plastic crowns. The way they were going, I had doubts they’d last much longer. One in particular seemed a bit wobbly on his feet.

One young woman with them had somehow attached a frisbee to her head, in delightfully mockery of the absurd hats women seem to love wearing to royal events. It made me laugh. So begins and ends The Line‘s coronation-related hat commentary.

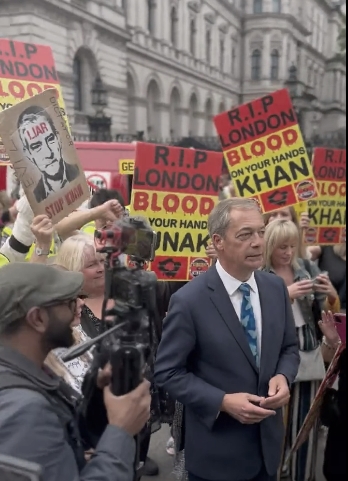

Quite near to the front of the viewing area, just off to the left of Nelson’s Column, was a group of a few dozen republican protesters. I have to remind my North American readers — I don’t mean U.S. Republicans, the of-late MAGA-infused husk of the once Grand Old Party. These are British republicans, an arguably even more baffling breed: these are the people that want Britain to be a republic. They too were a mixed group, but as I wandered over to join them, I did note something interesting. I had expected them to be younger and more ethnically diverse than the rest of the crowd. They weren’t. I don’t know if I’d go as far as saying that they were less diverse, but my sense was that, at least in terms of the age of the crowd of protesters, maybe they were a touch older than the rest? In any case, it would have been a near-run thing, but that was one of the only things that really jumped out at me about the protest. My assumption that they’d be younger, more diverse, more obviously progressive was wrong. If they’d dropped their yellow flags and banners and quit their chanting of “NOT MY KING!”, they’d have blended in with the rest.

It started to rain around this time. It’s England, of course it was raining. I’d come prepared with a rain jacket so wasn’t deterred, but the rain did have one admittedly lousy impact. Umbrellas. I’d been gradually able to work my way up quite close to the front of the crowd — I’d stuck close to the republicans and it seems that many people tried to give them a wide berth, and I’d been able to shuffle my way gradually forward. Nelson’s Column was to the right, behind me. To my right and front was Admiralty Arch. And off in the distance, but not too far, was Westminster Abbey itself. It was a pretty perfect place to view the procession.

But for the umbrellas. Once they opened up, all one could see was umbrellas.

And that’s how it stayed, to be honest. Troops began to march past in perfect ranks. Bands struck up patriotic songs. The crowd cheered and more than a few sang. One loud female voice — a surprisingly lovely one — struck up The Star Spangled Banner — which was either some kind of deliberate prank or just a very historically confused soul getting caught up in the moment. I heard the clopping of hooves and the crowd went absolutely wild, and suddenly, thousands of arms shot up into the air holding smartphones, every person present seeking a better angle for their videos. The arms and the umbrellas made it virtually impossible to see a damn thing. (See this video by a New York Times team: they must have been standing within 50 feet of where I was, a bit off to my left. You’ll see what I mean.)

That was from Matt Gurney’s sleep-deprived view of the procession from The Line (that’s not editorializing on my part — he hadn’t slept on the plane from Toronto and got to London at 7am on Coronation Day). In what seemed like a useful break in the public celebrations, he snuck away to get some sustenance and be out of the rain for a bit. When he returned it was lowlight time for the Republicans:

After I’d polished off the pint, I headed back out, back to the square, and that’s where things got interesting. I figured I’d get back to my former spot near the chanting republicans, and did so, no problem. But I noticed there suddenly seemed to be an awful lot of cops around … all heading that way. As in: right toward me, and the chanting people I was standing near. Oops. I left, working my way around the crowd, heading back the way I came from my hotel, and found myself actually facing a rank of advancing cops. Oops again. One had a badge that said inspector, and I walked right up and told him I was a Canadian journalist just watching things. He grinned at me and said, “Alright, mate, come this way,” and had a security guard walk me through the police. I thus ended up missing what has proven to be a controversial event and perhaps the only unhappy moment I know of during the coronation, at least in my area: a bunch of the chanting republicans were arrested just moments after I got out of dodge, and then large metal screen barriers were thrown up, closing off the square due to, apparently, overcrowding. People could leave but no one new could enter.

My sense, as I walked away, was that there was no reason to arrest anyone. (And as I said, this is proving controversial.) I hadn’t seen anything getting out of hand. There had been some chanting and counter-chanting and even some heckling back and forth, but it had all seemed in good enough spirits. Even some of the boos sent at the republicans — two young men with flags had been hamming it up in the main crowd, apart from the main blob of republicans — had seemed in good humour. I don’t know what the police saw or knew. But I couldn’t tell you why they’d moved then and not before, or later. As for overcrowding, I don’t think so. The square really wasn’t all that full. It seemed less full at that moment than it had been when the procession had passed on the way to the abbey. But the barriers seemed to go up quickly, everywhere. Literally everywhere.

And though I was glad to have avoided getting caught up in the Cops vs. Chanting Republicans, I was now on the wrong side of the barriers.

In The Critic, Kittie Helmick recounts finding herself in the vicinity of the “NOT MY KING!” group:

“You seem to find this whole thing rather amusing,” snapped a short angry man with a Not My King sign, about half an hour into the Republic protest against the coronation of King Charles III. I must admit I did. Kettled into a small enclave just off Trafalgar Square, an angry swell of old school socialists, Twitter anarchists, Lib Dem mums, eccentric vicars, boomer hippies, blue haired students and Covid conspiracists had somehow found themselves part of the coronation spectacle. Before the bells of St Martin in the Fields, the full shouty brunt of British republicanism was aimed at a bewildered stream of Chinese tourists and young families out for a day in London.

The survival of the British monarchy is one of the great wonders of modern history. Spending the morning of the coronation with Republic, it began to seem less mysterious. Despite everything in recent years, the Monarchy is still liked more than most of our institutions and probably every one of our elected politicians. No one gathered there could really explain why. The arguments were articulated in between the shouty chanting: things about “modern Democracy” and a “family of Lizards”, none of which quite landed the blow as the day unfolded around us.

Somewhere beyond the crowds, towards Westminster Abbey, an ageing, eccentric dandyish farmer, who secretly wants to be King of Transylvania, was being anointed in holy oil and crowned by an Archbishop wearing hearing aids in a seven hundred year old chair vandalised by 18th century schoolboys. All the while this ceremony was being fawned over across the world by everyone from Kay Burley to one of the world’s most remote tribes. None of it made sense, and that is precisely the point.

Earlier that morning, the CEO of Republic Graham Smith, a man not even the protestors could name, achieved the greatest success of his kind since Cromwell, by being arrested at the hands of the jobsworth Met. For a brief moment, a shiver of excitement spread through the protest. Whilst the country was entranced by a fugue of sombre ritual and Zadok the Priest, Republic were experiencing their own desired reality unfold on the streets of London. Here was a police state enforcing the will of a “politically illiterate” nation brainwashed by bunting and tabloid journalism. The mask was finally off. The incoherent gaggle of shouty slogans and reddit thread arguments made sense. The fight was here and now.

Except that was all a fantasy too. As stupid as the arrests were, nothing could disguise the fact this was a fringe event for a movement that just can’t seem to take off — a Coronation curio to gawp at. “They’re a bunch of wronguns, aren’t they?” said one bored steward to me as we watched a man larping Les Miserables as he chanted Not My King at a trio of giggling Chinese students. The deeper I dug into the many arguments and protestations offered as an alternative to the “fairytale” of monarchy, the more the core transgressive energy of British republicanism revealed itself. It is itself strangely twee and fantastical. Rid us of the Royals, and everything will become better. Gone will be the “psychological baggage” of Britain’s past holding us back. Democracy will triumph. The crown jewels will be sold off and spent on food banks. The plebs will not worship hereditary blood, but NHS rainbows. Britain will become less racist, elitist and classist. The left might even win an election. We could have a poet president like Ireland, a Lineker or a Stormzy shaking hands with the American president.