No one can question the dirtiness of international politics from 1870 onwards: it does not follow that it would have been a good thing to allow the German army to rule Europe. It is just possible that some rather sordid transactions are going on behind the scenes now, and that current propaganda “against Nazism” (cf. “against Prussian militarism”) will look pretty thin in 1970, but Europe will certainly be a better place if Hitler and his followers are removed from it. Between them these two books sum up our present predicament. Capitalism leads to dole queues, the scramble for markets, and war. Collectivism leads to concentration camps, leader worship, and war. There is no way out of this unless a planned economy can somehow be combined with the freedom of the intellect, which can only happen if the concept of right and wrong is restored to politics.

Both of these writers are aware of this, more or less; but since they can show no practicable way of bringing it about the combined effect of their books is a depressing one.

George Orwell, “The Road to Serfdom by F.A. Hayek / The Mirror of the Past by K. Zilliacus”, Observer, 1944-04-09.

July 8, 2019

May 25, 2019

February 26, 2019

Laissez-faire versus “Fairtrade”

In the Guardian, a sad tale of the fading bright hopes of the (relatively small number of) affluent westerners who passionately supported the “Fairtrade” movement:

When, in 2017, Sainsbury’s announced that it was planning to develop its own “fairly traded” mark, more than 100,000 people signed a petition condemning the move. Today, on the eve of Fairtrade Fortnight, the fact that most supermarkets have moved away from the standards developed by the Fairtrade Foundation is worrying.

While some grocery chains have sought the foundation’s stamp of approval, many have gone their own way. This means most consumers have little sense of which organisation is doing what to protect the wages and rights of developing world workers. Over the next two weeks, the foundation plans to focus its publicity efforts on cocoa farmers in west Africa and the way the Fairtrade mark can improve their lives.[…]

That is a sad situation. After the great financial crash of 2008, a commodity boom that lasted from 2013 to 2017 turned into a slump that has robbed farmers and developing world governments of vital cash. Just as they were managing to stabilise their finances and set aside money to invest, the world price tumbled and wiped out their profit. Fairtrade practices protect farmers from this sort of setback and allow them to plan for the future.

Of course they have their critics. These are most mostly from the US – people who favour unfettered markets and seek to undermine the Fairtrade ideal, saying it is a form of protectionism that dampens innovation and ultimately ruins farms.

Theirs is an almost religious adherence to the free market that discounts the gains in stability and security that Fairtrade provides, and the scope of the community premium to promote universal education and the rights of women.

But without large employers making strides to adopt the standardised and transparent Fairtrade practices put forward by the foundation, it will be left to consumers to drive the project forward.

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall responds:

The Guardian tells us that the Great White Hope of global trade, Fairtrade, isn’t in fact working. On the basis that no one seems to be doing very much of it. To which the answer is great – for the only fair trade is laissez faire.

This does not mean that Fairtrade should not have been tried – to insist upon that would be to breach our basic insistence upon the value of peeps just getting on with doing what they want, laissez faire itself. But the very value of that last is that we go try things out, see whether they work and if they don’t we stop doing them. If they do then great, we do more of them.

[…]

So, trying out Fairtrade, why not? Let’s go see how many other people feel the same way? In exactly the same way we find out whether people like Pet Rocks, skunk or Simon Cowell. Product gets put on the market we see whether it adds to human welfare or not. If people value it – and revealed preferences please, by actually buying it – at more than the use of those scarce resources in other uses then that’s adding to human welfare and long may it thrive. If it doesn’t, if it’s subtracting value from the human experience, then we’ll stop doing it as those trying go bust.

This is not an aberration of the system it is the system and it’s why laissez faire works. Peeps get to do whatever and we keep doing more of what works, less of what doesn’t.

Fairtrade? No, I never thought it was going to work as anything other than virtue signalling for Tarquin and Jocasta but that’s fine. Why shouldn’t Tarquin and Jocasta gain their jollies by virtue signalling? As it turns out, now that we’ve tried it, no one else gives a faeces*. So, we can stop. Except, obviously enough, for those specialist outlets like the Co Op where the odd can still gain their jollies. It being that very mark of a laissez faire, liberal, society that the jollies of the odd are still catered to in due proportion to the desire for them.

*From Gibbon, all the fun stuff’s in Latin.

October 1, 2017

Deirdre McCloskey on the rise of economic liberty

Samizdata‘s Johnathan Pearce linked to this Deirdre McCloskey article I hadn’t seen yet:

Since the rise during the late 1800s of socialism, New Liberalism, and Progressivism it has been conventional to scorn economic liberty as vulgar and optional — something only fat cats care about. But the original liberalism during the 1700s of Voltaire, Adam Smith, Tom Paine, and Mary Wollstonecraft recommended an economic liberty for rich and poor understood as not messing with other peoples’ stuff.

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care.

Adam Smith spoke of “the liberal plan of [social] equality, [economic] liberty, and [legal] justice.” It was a good idea, new in 1776. And in the next two centuries, the liberal idea proved to be astonishingly productive of good and rich people, formerly desperate and poor. Let’s not lose it.

Well into the 1800s most thinking people, such as Henry David Thoreau, were economic liberals. Thoreau around 1840 invented procedures for his father’s little factory making pencils, which elevated Thoreau and Son for a decade or so to the leading maker of pencils in America. He was a businessman as much as an environmentalist and civil disobeyer. When imports of high-quality pencils finally overtook the head start, Thoreau and Son graciously gave way, turning instead to making graphite for the printing of engravings.

That’s the economic liberal deal. You get to offer in the first act a betterment to customers, but you don’t get to arrange for protection later from competitors. After making your bundle in the first act, you suffer from competition in the second. Too bad.

In On Liberty (1859) the economist and philosopher John Stuart Mill declared that “society admits no right, either legal or moral, in the disappointed competitors to immunity from this kind of suffering; and feels called on to interfere only when means of success have been employed which it is contrary to the general interest to permit — namely, fraud or treachery, and force.” No protectionism. No economic nationalism. The customers, prominent among them the poor, are enabled in the first through third acts to buy better and cheaper pencils.

[…]

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care. True, liberty of speech, the press, assembly, petitioning the government, and voting for a new government are in the long run essential protections for all liberty, including the economic right to buy and sell. But the lofty liberties are cherished mainly by an educated minority. Most people — in the long run foolishly, true — don’t give a fig about liberty of speech, so long as they can open a shop when they want and drive to a job paying decent wages. A majority of Turks voted in favour of the rapid slide of Turkey after 2013 into neo-fascism under Erdoğan. Mussolini and Hitler won elections and were popular, while vigorously abridging liberties. Even a few communist governments have been elected — witness Venezuela under Chavez.

September 19, 2017

Even in a progressive educational bubble, this isn’t correct

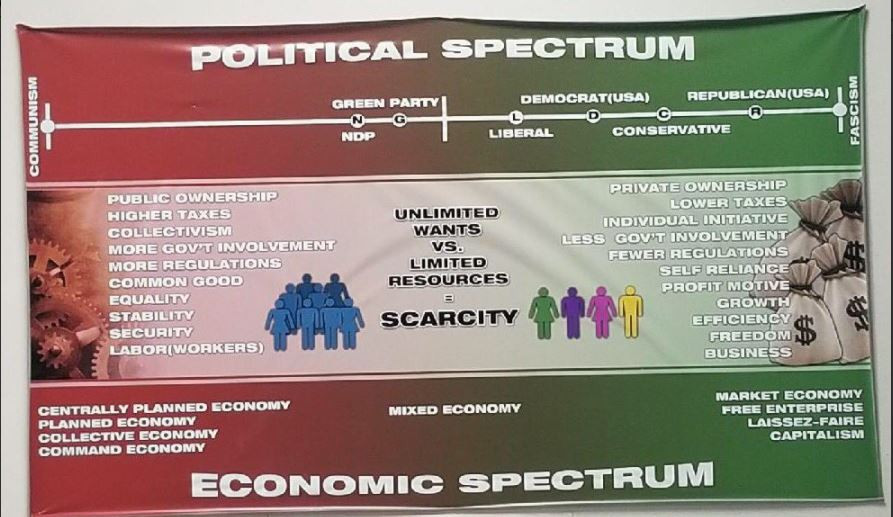

Holly Nicholas shared this photo, which is said to be from an Alberta school:

If this is indeed how public schools are presenting the political spectrum (and it’s unfortunately easy to believe that they do), the closest thing to a “centrist” party in Canada is the loony left Green Party … who somehow pip the NDP on the right. The far right end of the spectrum, Fascism, is graphically indicated to be all about “Market Economy, Free Enterprise, and Laissez-Faire Capitalism”, because as we all remember, Hitler and Mussolini were in no way fans of state intervention in the economy, right?

The graphic does, however, support certain shibboleths of the left including implying that libertarians (who are actually in favour of market economies, free enterprise, and laissez-faire capitalism) are in the same economic and political basket as actual fascists. Nice work, faceless agitprop graphic artist!

August 4, 2017

Harry Potter and the Economic Segregation of Muggles

Published on 3 Aug 2017

Harry Potter contains a ton of incredible lessons about society, authoritarianism, and the power of love and individualism in the face of people who would exclude others based on group identity. But something people don’t think about as much are some of the economic lessons that we can draw from a world segregated into wizards and muggles.

On this episode of Out of Frame, we take a look at what the world might look like if magic and non-magic people were actually allowed to trade and interact with each other without the Ministry of Magic obliviating and arresting people for it.

For a transcript of this episode and more engaging content, visit:

www.FEE.org

July 20, 2017

Deirdre McCloskey defines libertarianism as “Liberalism 1.0”

The introduction to her “Manifesto for a New American Liberalism, or How to Be a Humane Libertarian” [PDF] states:

I make the case for a new and humane American “libertarianism.”

Outside the United States libertarianism is still called plain “liberalism,” as in the usage of the president of France, Emmanuel Macron, with no “neo-” about it. That’s the L-word I’ll use here. The economist Daniel Klein calls it “Liberalism 1.0,” or, channeling the old C. S. Lewis book Mere Christianity on the minimum commitments of faith (1942-44, 1952), “mere Liberalism.” David Boaz of the Cato Institute wrote a lucid guide, Libertarianism — A Primer (1997), reshaped in 2015 as The Libertarian Mind. I wish David had called it The Liberal Mind.

In desperate summary for you Americans, Liberalism 1.0 is Democratic in social policy and Republican in economic policy and non-interventionist in foreign policy. It is in fact mainly against “policy,” which has to be performed, if there is to be a policy at all, through the government’s monopoly of violence. (To confirm this experimentally, try not paying your taxes; then try to escape from prison.) Liberals 1.0 believe that having little or no policy is a good policy.

That does not put the Liberals 1.0 anywhere along the conventional one-dimensional left-right line, stretching from a compelled right-conservative policy to a compelled left-”liberal” policy. The real liberals instead sit happily up on a second dimension, the non-policy apex of a triangle, so to speak, the base of which is the conventional axis of policy by violence. We Liberals 1.0 are neither conservatives nor socialists — both of whom believe, with the legal mind, as the liberal economist and political philosopher Friedrich Hayek put it in 1960, that “order [is] … the result of the continuous attention of authority.” Both conservatives and socialists, in other words, “lack the faith in the spontaneous forces of adjustment which makes the liberal accept changes without apprehension, even though he does not know how the necessary adaptations will be brought about.”

Liberals 1.0 don’t like violence. They are friends of the voluntary market order, as against the policy-heavy feudal order or bureaucratic order or military-industrial order. They are, as Hayek declared, “the party of life, the party that favors free growth and spontaneous evolution,” against the various parties of left and right which wish “to impose [by violence] upon the world a preconceived rational pattern.”

At root, then, Liberals 1.0 believe that people should not push other people around. As Boaz says at the outset of The Libertarian Mind, “In a sense, there have always been but two political philosophies: liberty and power.” Real, humane Liberals 1.0 […] believe that people should of course help and protect other people when we can. That is, humane liberals are very far from being against poor people. Nor are they ungenerous, or lacking in pity. Nor are they strictly pacifist, willing to surrender in the face of an invasion. But they believe that in achieving such goods as charity and security the polity should not turn carelessly to violence, at home or abroad, whether for leftish or rightish purposes, whether to help the poor or to police the world. We should depend chiefly on voluntary agreements, such as exchange-tested betterment, or treaties, or civil conversation, or the gift of grace, or a majority voting constrained by civil rights for the minority.

To use a surprising word, we liberals, whether plain 1.0 or humane, rely chiefly on a much-misunderstood “rhetoric,” despised by the hard men of the seventeenth century such as Bacon and Hobbes and Spinoza, but a practice anciently fitted to a democratic society. Liberalism is deeply rhetorical, the exploration (as Aristotle said) of the available means of non-violent persuasion. For example, it’s what I’m doing for you now. For you, understand, not to you. It’s a gift, not an imposition. (You’re welcome.)

June 21, 2017

June 8, 2017

Words & Numbers: Earning Profits is Your Social Responsibility

Published on 7 Jun 2017

“We tend to demonize people who make money – how dare they have more than us? But that negative reaction forgets the voluntary role we play in profit-making every day. This week in Words and Numbers, Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan discuss just how good it is to earn a profit, and the vital difference between that and forcing money from people.”

January 27, 2017

QotD: Greed

Well first of all, tell me: Is there some society you know that doesn’t run on greed? You think Russia doesn’t run on greed? You think China doesn’t run on greed? What is greed? Of course, none of us are greedy, it’s only the other fellow who’s greedy. The world runs on individuals pursuing their separate interests. The great achievements of civilization have not come from government bureaus. Einstein didn’t construct his theory under order from a bureaucrat. Henry Ford didn’t revolutionize the automobile industry that way. In the only cases in which the masses have escaped from the kind of grinding poverty you’re talking about, the only cases in recorded history, are where they have had capitalism and largely free trade. If you want to know where the masses are worse off, worst off, it’s exactly in the kinds of societies that depart from that. So that the record of history is absolutely crystal clear, that there is no alternative way so far discovered of improving the lot of the ordinary people that can hold a candle to the productive activities that are unleashed by the free-enterprise system.

February 16, 2016

February 14, 2016

QotD: President Herbert Hoover’s lasting economic legacy

Until March 1933, these were the years of President Herbert Hoover — the man that anti-capitalists depict as a champion of non-interventionist, laissez-faire economics.

Did Hoover really subscribe to a “hands off the economy,” free-market philosophy? His opponent in the 1932 election, Franklin Roosevelt, didn’t think so. During the campaign, Roosevelt blasted Hoover for spending and taxing too much, boosting the national debt, choking off trade, and putting millions of people on the dole. He accused the president of “reckless and extravagant” spending, of thinking “that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible,” and of presiding over “the greatest spending administration in peacetime in all of history.” Roosevelt’s running mate, John Nance Garner, charged that Hoover was “leading the country down the path of socialism.” Contrary to the modern myth about Hoover, Roosevelt and Garner were absolutely right.

The crowning folly of the Hoover administration was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed in June 1930. It came on top of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which had already put American agriculture in a tailspin during the preceding decade. The most protectionist legislation in U.S. history, Smoot-Hawley virtually closed the borders to foreign goods and ignited a vicious international trade war.

Officials in the administration and in Congress believed that raising trade barriers would force Americans to buy more goods made at home, which would solve the nagging unemployment problem. They ignored an important principle of international commerce: trade is ultimately a two-way street; if foreigners cannot sell their goods here, then they cannot earn the dollars they need to buy here.

Foreign companies and their workers were flattened by Smoot-Hawley’s steep tariff rates, and foreign governments soon retaliated with trade barriers of their own. With their ability to sell in the American market severely hampered, they curtailed their purchases of American goods. American agriculture was particularly hard hit. With a stroke of the presidential pen, farmers in this country lost nearly a third of their markets. Farm prices plummeted and tens of thousands of farmers went bankrupt. With the collapse of agriculture, rural banks failed in record numbers, dragging down hundreds of thousands of their customers.

Hoover dramatically increased government spending for subsidy and relief schemes. In the space of one year alone, from 1930 to 1931, the federal government’s share of GNP increased by about one-third.

Hoover’s agricultural bureaucracy doled out hundreds of millions of dollars to wheat and cotton farmers even as the new tariffs wiped out their markets. His Reconstruction Finance Corporation ladled out billions more in business subsidies. Commenting decades later on Hoover’s administration, Rexford Guy Tugwell, one of the architects of Franklin Roosevelt’s policies of the 1930s, explained, “We didn’t admit it at the time, but practically the whole New Deal was extrapolated from programs that Hoover started.”

To compound the folly of high tariffs and huge subsidies, Congress then passed and Hoover signed the Revenue Act of 1932. It doubled the income tax for most Americans; the top bracket more than doubled, going from 24 percent to 63 percent. Exemptions were lowered; the earned income credit was abolished; corporate and estate taxes were raised; new gift, gasoline, and auto taxes were imposed; and postal rates were sharply hiked.

Can any serious scholar observe the Hoover administration’s massive economic intervention and, with a straight face, pronounce the inevitably deleterious effects as the fault of free markets?

Lawrence W. Reed, “The Great Depression was a Calamity of Unfettered Capitalism”, The Freeman, 2014-11-28.

November 18, 2015

Adam Smith – The Inventor of Market Economy I THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Published on 22 Feb 2015

Adam Smith was one of the first men who explored economic connections in England and made clear, in a time when Mercantilism reigned, that the demands of the market should determine the economy and not the state. In his books Smith was a strong advocator of the free market economy. Today we give you the biography of the man behind the classic economic liberalism and how his ideas would change the world forever.

April 9, 2014

Being “pro-business” does not mean the same as being “pro-market”

It’s a common misunderstanding (especially with people who don’t know what laissez faire actually means):

For years, Republicans benefited from economic growth. So did pretty much everyone else, of course. But I have something specific in mind. Politically, when the economy is booming — or merely improving at a satisfactory clip — the distinction between being pro-business and pro-market is blurry. The distinction is also fuzzy when the economy is shrinking or imploding.

But when the economy is simply limping along — not good, not disastrous — like it is now, the line is easier to see. And GOP politicians typically don’t want to admit they see it.

Just to clarify, the difference between being pro-business and pro-market is categorical. A politician who is a “friend of business” is exactly that, a guy who does favors for his friends. A politician who is pro-market is a referee who will refuse to help protect his friends (or anyone else) from competition unless the competitors have broken the rules. The friend of business supports industry-specific or even business-specific loans, grants, tariffs, or tax breaks. The pro-market referee opposes special treatment for anyone.

[…]

GOP politicians can’t have it both ways anymore. An economic system that simply doles out favors to established stakeholders becomes less dynamic and makes job growth less likely. (Most jobs are created by new businesses.) Politically, the longer we’re in a “new normal” of lousy growth, the more the focus of politics turns to wealth redistribution. That’s bad for the country and just awful politics for Republicans. In that environment, being the party of less — less entitlement spending, less redistribution — is a losing proposition.

Also, for the first time in years, there’s an organized — or mostly organized — grassroots constituency for the market. Historically, the advantage of the pro-business crowd is that its members pick up the phone and call when politicians shaft them. The market, meanwhile, was like a bad Jewish son; it never called and never wrote. Now, there’s an infrastructure of tea-party-affiliated and other free-market groups forcing Republicans to stop fudging.

A big test will be on the Export-Import Bank, which is up for reauthorization this year. A bank in name only, the taxpayer-backed agency rewards big businesses in the name of maximizing exports that often don’t need the help (hence its nickname, “Boeing’s Bank”). In 2008, even then-senator Barack Obama said it was “little more than a fund for corporate welfare.” The bank, however, has thrived on Obama’s watch. It’s even subsidizing the sale of private jets. Remember when Obama hated tax breaks for corporate jets?

July 2, 2012

What value do speculators offer?

In most newspapers, you don’t need to wait long to read some journalist beating up on evil speculators for the “damage” they do and the claimed “uselessness” of their activities. Tim Worstall points out that speculators are actually essential to smooth operation of free markets:

What is it that the speculator in food manages to achieve? They move prices through time. At the moment, there’s a drought, and so we think there will be less corn available for consumption next year, so its price goes up.

What would we like to happen? Should prices stay stable? We would all carry on using the amount of corn that we originally thought we’d get. And we’d run out — there may even be a famine. People tend to die in famines.

So what we’d actually like to happen is for people to prepare by consuming a bit less corn this year.

Some of this should come from substitution: farmers will feed wheat to animals not corn. Consumers might move from grits to weetabix for breakfast. Perhaps the fools putting corn into cars will move over to sugar cane to make ethanol from.

We would also like a supply effect: those who are currently growing corn might add a bit more fertiliser, take more care in harvesting, make sure less gets spoiled or lost in transport.

Rising prices causes both of those pretty neatly. Put up the price and people will use less, while suppliers will make more. And what is it that the speculators on the futures markets have done in response to this report of drought? They have raised prices.