Feral Historian

Published 15 Aug 2025Soviet science fiction is a long winding road and it starts with Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star. Let’s start down that road.

00:00 Intro

03:15 Introducing Martian Socialism

06:35 Tektology

10:03 Crafting Communism

15:08 Mars Has Problems

19:06 Old Man of the Mountain

20:32 The Engineer Menni

(more…)

January 7, 2026

Red Star: The Dawn of Soviet Sci-Fi

January 2, 2026

QotD: From Rousseau to Marx, Hegel to Gramsci

How did we get here? Can those of us who understand what Communism and socialism would mean for our republic win the election that will be upon us in less than 100 days? Only if we understand how on earth Karl Marx’s ideology survived the end of the Cold War to flourish and grow here in America.

The fundamentals are clear enough. The New Left in America, which is the conveyor belt for everything from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s (D-N.Y.) Green New Deal to Black Lives Matter, can trace its genetic roots back to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who almost single-handedly upturned centuries of Western philosophical and theological wisdom.

Instead of believing that man is fallen, fatally flawed, and prone to selfishness and evil, Rousseau denied the reality of thousands of years of human history and posited that man is inherently good. Further, this goodness could be maximized by engineering society away from individual rights and liberties, prioritizing communal good, communal needs, and the communal will.

Thus civilization built according to how man actually behaves in real life fell out of favor; and eventually, Karl Marx’s collectivist ideology predicated on the subversion of individual human souls to the common interest (as defined by political leaders) gained steam.

Like an ideological scrapbooker, Marx picked and purloined the ideas of others to build his theory. Socialism is but a temporary stepping stone towards the eventual and inevitable end-state of all mankind, the utopian “Worker’s Paradise.” Marx stole the “inevitability” factor from Hegel and his eponymous “dialectic.”

Hegel, a profoundly religious man, unlike the rabidly and militantly atheist Marx, saw the history of man as a perpetual progression, a series of qualitative improvements in our collective lot as one new idea (antithesis) impacted upon an existing idea (thesis) and resulted in an improved conceptualization (synthesis) that has more truth value than the previous two ideas combined. This progression, so Hegel believed, would increase our enlightenment, until we perceived the ultimate synthesis, the purest version of truth’s expression, which is God himself.

Marx took Hegel’s key inevitability dynamic and removed the metaphysical elements. For Marx the intangible was irrelevant. His “dialectic materialism” posits that thesis and antithesis are instead expressions of the inherent conflict within society — the clash between the have and have nots, the oppressor and the oppressed, the capitalist and the exploited workers — which will result in a final revolution permanently removing class distinction and conflict from society.

This garbage is what Karl Marx sold the world with his books Das Kapital and the Communist Manifesto. And incredibly, some people believed this rubbish. So much so that they used it as a blueprint to sabotage and subvert multiple nations around the world, starting with czarist Russia and stretching all the way to Cuba and China. But then there was a problem. In all their attempts to effect a Communist revolution west of the Russian Empire, Marx’s followers would fail. America was an especially tough nut for Marxists to crack, because of how our nation was born.

America’s Founders, knowing full well that man is fallen and tends toward the selfish and the bad, built America with a system of separation of powers and also bequeathed us a written Constitution founded not on some absurd utopian collectivist vision of society, but built upon the recognition of the liberty of the individual and the unalienable God-given rights we each possess. Despite the advent of Progressive presidents, such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, America remained staunch in its resistance to socialism. Marx’s disciples, however, were not ready to surrender.

This is where the influence of a hunchback Italian cripple comes in.

Antonio Francesco Gramsci is the ideational grandfather to all that threatens modern America and our freedoms today, from AOC’s Green New Deal to the violence of Antifa. His writings, penned in an Italian prison cell, would be leveraged by the Hungarian Jewish writer and politician, Gyӧrgy Lukacs, each sharing the same conviction: Communism had failed in established Western democracies — as opposed to the backward and mostly peasant society of czarist Russia — because these societies are too resilient and too developed. For Marxism to flourish in the rest of Europe and America, these “bourgeois” societies must be dismantled piece by piece. From the inside.

The conceptual progeny of that realization leads straight to the panoply of Democratic Party articles of belief today — from Obamacare’s unprecedented intrusion into private healthcare choices to the anti-scientific insanity of transgenderism and beyond. This isn’t a random accusation, devoid of context. It’s not some accusation floating in space. The path from Gramsci and Lukacs to Ocasio-Cortez and Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) is a path that may be mapped historically, geographically, and institutionally.

Sebastian Gorka, “From Alinsky to AOC: Will Communism Finally Win in America?”, American Greatness, 2020-07-29.

Update, 3 January: Welcome, Instapundit readers! Please do have a look around at some of my other posts you may find of interest. I send out a daily summary of posts here through my Substack – https://substack.com/@nicholasrusson that you can subscribe to if you’d like to be informed of new posts in the future.

November 22, 2025

“Whig history”

If you’ve read any history books written before the Second World War (aside from explitly Marxist interpretations), you’ll probably recognize the worldview which, subtly or overtly, informed the stories being told (and those not mentioned). On her Substack, Mary Catelli discusses “the Whig interpretation of history”:

Among the many perils of viewpoint that lurk in your path when you read history, one of the nastiest is the Whig Interpretation of History, and its variants, and other teleological views.

The original interpretation, popular in British history writing of the 19th century, was that all of history had been aiming for the wonderfully wonderful wonder that was 19th century Britain. And if it was not quite so smooth as a train ride gliding over well-laid tracks, it was unnecessary to point out minor details.

The most disastrous effect, for the reader, is that the things of the past are described for their presumed effect on the progress toward that aim. They were not described for their actual effect on the era, or how they appeared to the people of that era (possibly more important for the fiction writer), which is what a reader using them for that era needs. Down to and including excluding vital details as unimportant.

(Obviously, “development of what they regard as progress” books are more or less resistant to this, though they can press some very odd things into the service of their thesis, and sandpaper off quite a bit of things they deem anomalies. It is when it colors works about something else — or nominally about something else — that the peril really arises.)

Plus of course any coloring the viewpoint gives them in regarding the people of the era as stepping stones toward the ideal future. In particular, the heroes and villains are assigned not for the moral character of their deeds but whether they sped history along the right path. Frequently enough, any openly and clearly stated motives by the historical figures will be breezed over for the “real” motives according to the historian’s agenda. Some quote the primary source and not even apparently noticing that it contradicts the agenda before writing as if the historical figures’ intentions matched the agenda.

H. G. Wells, in The Outline of History, gets all starry-eyed about any attempt, or success, at union between countries because he’s looking forward to the beneficent World State, regardless of how the union was imposed, and what its consequences were, and again looking with a jaundiced eye on any division regardless of how justified.

It would be easier if the issue were limited to the historians of that school, but, of course, anyone who regards history in light of a progress toward the wonderful present — or future — will have the same issues. World War I hit the original Whig interpretation quite hard, but the Marxist interpretation kept roaring along, and is not quite dead yet.

October 7, 2025

QotD: “That wasn’t real communism …”

Leftism has always been a ridiculously reductive creed, but the One Thing all Leftism reduces to has undergone a radical shift. For Marx, of course, the One Thing was that thesis-antithesis-synthesis Hegelian schmear. Hegel’s ontology claims that the universe is talking to itself. Literally. That thesis-antithesis-synthesis thing, summarized by the untranslatable German word Aufheben (“self-transcendence”; something like that), is literally a debate the World Spirit (or whatever) is having with itself.

All Karl Marx did was bring that down to the material level — it’s not the world spirit having a debate with itself, it’s the world, the material object. Both the debate and its conclusion are made manifest in History, capital-H, which is why Marx was one of a long line of gurus who claimed to make History into a hard science. That “wrong side of History” stuff the Left is always going on about? That’s why they use that phrase so much, and why it has such emotional resonance for them. If you’re a Dialectical Materialist, being against Socialism is like being against gravity. What could possibly be the point? You’re just being perverse, comrade, and on some level you must know that …

Alas, History isn’t a hard science. There are patterns, of course, any fool can see that, but those patterns are the intersection of human nature and emergent behavior. The proof is in the writings of Karl Marx himself — every prediction the man ever made was not just wrong, but ludicrously so, and after getting burned a few times he admitted in his letters to writing in such a way that he could never be “proven” wrong. See also: The complete history of the Soviet Union, 1917-1991, and as a side note, you can tell the intellectual caliber of Socialism’s defenders by the fact that they trot out the excuse “That wasn’t real Communism; real Communism has never been tried.” Ah, so Lenin — he of Marxism-Leninism — wasn’t a true Communist. They’ll shoot you for saying that in, say, China, but do please go on …

Severian, “Power”, Founding Questions, 2022-02-02.

Update, 8 October: Welcome, Instapundit readers! Please do have a look around at some of my other posts you may find of interest. I send out a daily summary of posts here through my Substack – https://substack.com/@nicholasrusson that you can subscribe to if you’d like to be informed of new posts in the future.

October 2, 2025

November 19, 2024

The state and society

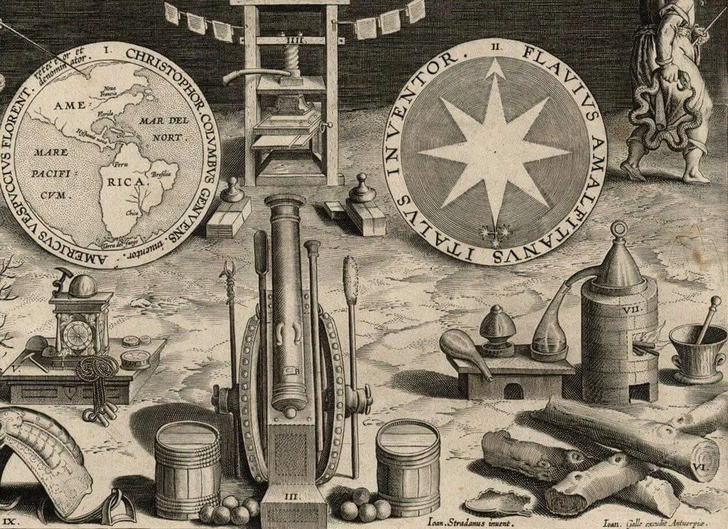

Lorenzo Warby explains why Karl Marx was wrong about the origins of what he called “the three great inventions” and therefore also mistaken about the societal impact of those inventions:

Gunpowder, the compass, and the printing press were the 3 great inventions which ushered in bourgeois society. Gunpowder blew up the knightly class, the compass discovered the world market and founded the colonies, and the printing press was the instrument of Protestantism and the regeneration of science in general; the most powerful lever for creating the intellectual prerequisites.

Karl Marx, “Division of Labour and Mechanical Workshop. Tool and Machinery” in Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63, Part 3) Relative Surplus Value.

With this quote we can see what is wrong both with Marx’s notion of the role of technology in social causation and with a very common notion of the relationship between state and society.

The false — but very common — view of the relationship of state and society is that the state is a product of its society, that the state emanates from its society. This gets the dominant relationship almost entirely the wrong way around. It is far more true to say that the state is a fundamental structuring element of the social dynamics of the territory it rules rather than the reverse.

It is perhaps easiest to see this by noting the glaring flaw in Marx’s reasoning. The gunpowder, the compass and the printing press were all originally Chinese inventions. Indeed, Europe acquired — via intermediaries — gunpowder and the compass from China. (Gutenberg’s printing press appears to have been an independent invention.)

Source: Nova Reperta Frontispiece, 1588.

Yet, as Marx was very well aware, China did not develop a bourgeoisie in his sense. Indeed, Marx’s notion of the Asiatic mode of production grappled with precisely that lack.1

In 1620, Sir Francis Bacon wrote in his Instauratio magna that

… printing, gunpowder, and the nautical compass … have altered the face and state of the world: first, in literary matters; second, in warfare; third, in navigation …

This was true of the effect of these inventions in European, but not Chinese, hands.

Why were these inventions globally transformative in European, but not Chinese hands? Because of the differences in the structure of European state(s) compared to the Chinese state.

Unified China …

The first difference is that the European states were states, plural. Europe had competitive jurisdictions, it had centuries of often intense inter-state conflict. From the Sui (re)unification (581) onwards China was, with brief interruptions, a single polity.2 What the evidence — both Chinese and Roman — shows quite clearly is that civilisational unity in a single polity is bad for institutional, technological and intellectual development.

The second difference is with the internal structure of European states compared to the Chinese state. The Sui dynasty, by introducing the Keju, the imperial examination — refining the use of appointment by exam that went back to the Warring States period — created a structure that directed Chinese human capital to the service of the Emperor.

There were three tiers of examinations (local, provincial, palace). You could sit for them as often as you wished. So a significant proportion of Chinese males devoted decades of their lives to attempting to pass the exams. Over time, the exams became more narrowly Confucian — probably because it required a high level of detailed mastery, so had more of a sorting effect — thereby promoting intellectual conformism.

[…]

… and divided Europe

Conversely, when gunpowder, the compass and the printing press came to Europe, European states already had a military aristocracy; self-governing cities; an armed mercantile elite; organised religious structures; so a rich array of cooperative institutions. Moreover, kin-groups had been suppressed across manorial Europe, forcing — or giving the social space for — alternative mechanisms for social cooperation to evolve.3, 4 In particular, due [to] its self-governing cities with armed militias, medieval Europe had an (effectively) armed mercantile elite before gunpowder, the compass or printing reached Europe.

Alfonso IX of Leon and Galicia (r.1188-1230) first summoned the Cortes of Leon in 1188. This became the start of the first institutionalised use of merchant representatives in deliberative assemblies. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (r.1155-1190) had tried something similar earlier, but the mercantile elites of North Italy preferred de facto independence, defeating him at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

The first European reference to the compass is in a text written some time between 1187 and 1202, with its use appearing to expand over the 1200s. The first reference to gunpowder in Europe is not until 1267 and it took centuries before gunpowder played a major role in European warfare.

Both the compass and gunpowder really only have transformative effects from the late C15th onwards, which is also when the printing press is spreading across Latin Europe. By that time, medieval Europe has already become a machine culture and it had been for centuries the civilisation with the most powerful mercantile elite. A reality driven by competitive jurisdictions, a rural-based military aristocracy, law that was not based on revelation (so it could entrench social bargains), suppression of kin-groups, and self-governing cities.

Competition between European states was a powerful driver of the transformative use of technologies. But so was the level of striving within such states: adventurers able to mobilise resources — and seeking wealth, power, prestige — had far more room to operate (and receive official sanction) in Europe than in China.

In other words, the differences in the development and use of technology — and in social dynamics and formations — between China and medieval Europe was fundamentally driven by the differences in state structures, in how the relevant polities worked.

1. Marx was not an honest intellectual reasoner:

As to the Delhi affair, it seems to me that the English ought to begin their retreat as soon as the rainy season has set in in real earnest. Being obliged for the present to hold the fort for you as the Tribune’s military correspondent I have taken it upon myself to put this forward. NB, on the supposition that the reports to date have been true. It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way.

Marx to Engels, [London,] 15 August 1857, (emphasis in the original).2. The Song (960-1279) failed to fully unify China, but they were the only significant Han polity. That the Song were effectively within a mini-state system does seem to have affected their policies, including the unusually — for a Chinese imperial dynasty — strong focus on trade and technological development.

3. Kin-groups had already been suppressed in the city-states of the Classical world, including Rome. They re-emerged with the incoming Germanic peoples, and then were suppressed again by the Church and the manorial elite, remaining in the agro-pastoralist Celtic fringe and Balkan uplands.

4. Economists Avner Greif and Guido Tabellini define clan (i.e. kin-group) as “a kin-based organization consisting of patrilineal households that trace their origin to a (self-proclaimed) common male ancestor“. They contrast this with a corporation: “a voluntary association between unrelated individuals established to pursue common interests“. They note they perform similar functions: “they sustained cooperation among members, regulated interactions with non-members, provided local public or club goods, and coordinated interactions with the market and with the state“. Triads, tongs and cults can also perform these functions.

September 27, 2024

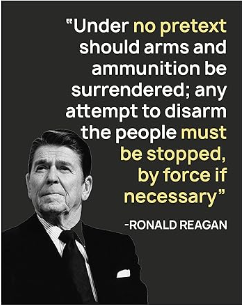

Ronald Reagan never said this … but Karl Marx did

At The Take, Jon Miltimore discusses a fake Ronald Reagan quote-on-a-poster being sold through Amazon and reveals that the quote actually originates with Karl Marx:

For just $9.99, people can go on Amazon and buy wall art of Ronald Reagan apparently defending the Second Amendment.

“Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered,” the text reads next to a picture of Reagan; “any attempts to disarm the people must be stopped, by force if necessary”.

There are a few problems with the quote, but the biggest one is that Reagan never said it.

As numerous fact checkers have noted — including Reuters, Snopes, Factcheck.org, and Politifact — the author of the quote is none other than Karl Marx, the German philosopher and author of The Communist Manifesto who used language nearly verbatim to this in an 1850 address in London.

“Under no pretext should arms and ammunition be surrendered; any attempt to disarm the workers must be frustrated, by force if necessary,” Marx said in his “Address of the Central Committee to the Communist League“.

Marxists Not Embracing Marx’s Messaging?

In fairness to the many internet users duped by the fake Reagan meme, the quote sounds a bit like something Reagan could have said (though it’s highly unlikely the Gipper, a skilled and careful orator, would have ever said “by force if necessary”).

Reagan, after all, generally — though not universally — supported gun rights and was skeptical of efforts to restrict firearms.

“You won’t get gun control by disarming law-abiding citizens,” Reagan famously noted in a 1983 speech.

Some might be surprised that Marx and Reagan had similar views on gun control. Marx was of course the father of communism, whereas Reagan was famously anti-communist. Moreover, Marx’s modern disciples are staunch supporters of gun control, whether they identify as socialists or progressives.

“Guns in the United States pose a real threat to public health and safety and disproportionately impact communities of color,” Nivedita Majumdar, an associate professor of English at John Jay College, wrote in the Marxist magazine Jacobin. “Their preponderance only serves corporate interests, a corrupt political establishment, and an alienated capitalist culture.”

This distaste for guns goes beyond socialist magazines. As The Atlantic reported during the 2020 presidential election cycle, progressive politicians are increasingly embracing more stringent federal gun control laws.

“No longer are primary candidates merely calling for tighter background checks and a ban on assault weapons,” journalist Russell Berman wrote; “in 2019, contenders like Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey and Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas were calling for national licensing requirements and gun-buyback programs”.

The point here is not to disparage politicians like O’Rourke and Booker as “Marxists”, a label they’d almost certainly object to. The point is that progressive politicians like Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) might channel Marx in their class rhetoric, but they are not embracing his messaging when it comes to the proletariat’s access to firearms.

As it happens, this is a common theme with Marxists throughout history.

September 15, 2024

June 18, 2024

December 8, 2023

QotD: Prices as information

Price = information, gang. Adam Smith said that any item’s real value is what its purchaser is willing to pay, and this is exactly the kind of thing he was talking about.

Let’s all take another huge toke and return to our Libertarian paradise, where all conceivable information is both completely accurate and totally free to circulate. And since we’re now all so very, very mellow, let’s give Karl Marx due credit. One of his main gripes with “capitalism” is that it “commodifies” everything. Everything has its price under “capitalism”, Marx said, even stuff that shouldn’t – human life, human dignity. Since this is a college classroom and I’m the prof, I can assign some homework. Go google up “kid killed over sneakers”. You can always find stories like that. Put your natural, in-many-ways-admirable young person’s urge to rationalize aside, and simply consider the information. What were those Air Jordans really worth, based on the stuff we’ve learned today?

See what I mean? Marx had a point. What are those sneakers worth, considered from the standpoint of “demand”? Obviously more than whatever a human life is worth, considered from the same standpoint. Hence Marxism’s enduring appeal to young people whose hearts are in the right place. “Commodificiation”, or “reification” as he sometimes called it, is very real, and very nasty …

Severian, “Velocity of Information (I)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-26.

November 18, 2023

QotD: Teaching Marx’s Labour Theory of Value in university

You have to deal with Marx and Marxists in every nook and cranny of the ivory tower, of course, but when you teach anything in modern history you have to confront him head on. Since Marx was a shit-flinging nihilist pretending to be a philosopher while masquerading as an economist, economics is the easiest entry point to his thought. So I’d go at him head-on.

The Labor Theory of Value makes intuitive sense, especially to college kids, who consider themselves both idealists and socially sophisticated. So, I’d tell them, we all agree: Nike’s sneakers cost $2 to make, but sell for $200; therefore, the other $198 must be capitalist exploitation, right? In a socially-just world, sneakers would never cost more than $2, since that’s the amount of “socially useful” labor that went into making them.

To really get them thinking, at that point I’d offer to trade them my shoes, which were of course the butt-ugliest things I could find, bought special at the local Salvation Army just for that purpose. “These cost $2,” I’d tell them. “They’re my social justice shoes. Who’s willing to trade? Oh, nobody? Why ever not?” Or I’d come to class in a plain Wal-Mart t-shirt, on which I’d written “I Heart [This University]” in Magic Marker. Same deal, I’d tell them. “The stuff you guys are wearing sends the same message, but I’ve been in the bookstore, I know for a fact that the hoodie you’re wearing [pointing to the most dolled-up Basic Becky I could find] costs $75. My shirt only cost $2. We’re both telling the world that we love [this university], but yours cost a whole lot more. You, Becky, are taking like $73 out of the mouths of poor people by wearing that … right?”

Repeat as often as needed, until they get the idea that “price” isn’t the same thing as “cost”. This isn’t physics class, I’d tell them, where we can assume away important real-world stuff like friction. Out here in the real world, we have to take stuff like “overhead” and “taxes” into account, such that even if those ugly sneakers or that crappy college-logo t-shirt only “cost” $2 at the point of manufacture, getting them onto the shelves at the the store here in College Town adds a whole bunch more. And then there’s demand, which we’ve already covered. I offered to trade y’all my shoes. Hell, I offered to give away my homemade t-shirt, and nobody took me up on it. You might change your tune if you were naked – and here we will note that this was the kind of situation Karl Marx was putatively addressing – but if you have any choice at all you’ll stick with what you have, because nobody in his right mind wants to wander around campus in a homemade t-shirt …

In short, I’d tell them, price is information. Done right – in an absolutely free market, the capital-L Libertarian paradise, which is of course as bong-addled a fantasy as Marx’s – price is perfect information. Nike’s sneakers don’t sell for $200 because that’s what it cost to make them. The $200 is the aggregate of all those costs we talked about before – cost of materials, labor, transportation, taxes, and, as we’ve seen by the fact that y’all still won’t trade me shoes, the most important piece of information, demand.

Severian, “Velocity of Information (I)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-26.

September 5, 2023

August 2, 2023

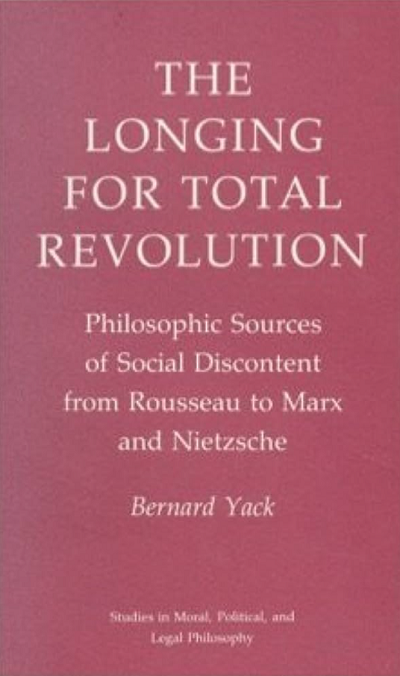

You say you want a revolution …

The latest book review from the Psmiths is Bernard Yack’s The Longing for Total Revolution: Philosophic Sources of Social Discontent from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsche, by John Psmith:

This is a book by Bernard Yack. Who is Bernard Yack? Yack is fun, because for a mild-mannered liberal Canadian political theorist he’s dropped some dank truth-bombs over the years. For example, check out his short and punchy 2001 journal article “Popular Sovereignty and Nationalism” if you need a passive-aggressive gift for the democratic peace theorist in your life.1 The subject of that essay is unrelated to the subject of the book I’m reviewing, but the approach, the method, and the vibe are similar. The general Yack formula is to take some big trendy topic (like “nationalism”) and examine its deep philosophical and intellectual substructure while totally refusing to consider material conditions. He’s kind of like the anti-Marx — in Yack’s world not only do ideas have consequences, they’re about the only things that do. Even when this is unconvincing, it’s usually very interesting.

The topic of this book is radicalism in the ur-sense of “a desire to get to the root”. What Yack finds interesting about radicalism is that it’s so new. It’s a surprising fact that the entire idea of having a revolution, of burning down society and starting again with radically different institutions, was seemingly unthinkable until a certain point in history. It’s like nobody on planet Earth had the idea, and then suddenly sometime in the 17th or 18th century a switch flips and it’s all anybody is talking about. We’re used to that sort of pattern for scientific discoveries, or for very original ways of thinking about the universe, but “let’s destroy all of this and try again” isn’t an incredibly complex or sophisticated thought, so why did it take so many millennia for somebody to have it?

Well, first of all, is this claim even true? One thing you do see a lot of in premodern history is peasant rebellions, but dig a little deeper into any of them and the first thing you notice is that (sorry vulgar Marxists)2 there’s nothing especially “revolutionary” in any of these conflagrations. The most common cause of rebellion is some particular outrage, and the goal of the rebellion is generally the amelioration of that outrage, not the wholesale reordering of society as such. The next most common cause of rebellions is a bandit leader who is some variety of total psycho and gets really out of control. But again, prior to the dawn of the modern era, these psychos led movements that were remarkably undertheorized. The goal was sometimes for the psycho to become the new king, sometimes the extinguishment of all life on earth, but you hardly ever saw a manifesto demanding the end of kings as such. Again, this is weird, right? Is it really such a difficult conceptual leap to make?

Peasant rebellions are demotic movements, but modern revolutions are usually led by frustrated intellectuals and other surplus elites. When elites did get involved in pre-modern rebellions, their goals were still fairly narrow, like those of the peasants — sometimes they wanted to slightly weaken the power of the king, other times they wanted to replace the king with his cousin. But again this is just totally different in kind from the 18th century onwards, when intellectuals and nobles are spending practically all of their time sitting around in salons and cafés, debating whose plan for the total overhaul of society, morality, and economic relations is best.

The closest you get to this sort of thing is the tradition of Utopian literature, from Plato’s Republic to Thomas More, but what’s striking about this stuff is how much ironic distance it carried — nobody ever plotted terrorism to put Plato’s or More’s theories into practice. Nobody ever got really angry or excited about it. But skip forward to the radical theorizing of a Rousseau or a Marx or a Bakunin, and suddenly people are making plans to bomb schools because it might bring the Revolution five minutes closer. So what changed?

Well this is a Bernard Yack book, so the answer definitely isn’t the printing press. It also isn’t secularization, the Black Death, urbanization, the Reformation, the rise of industrial capitalism, the demographic transition, or any of the dozens of other massive material changes that various people have conjectured as the cause of radical political ferment. Instead Yack points to two abstract philosophical premises: the first is a belief in the possibility of “dehumanization”, the idea that one can be a human being and yet be living a less than human life. The second is “historicism” in the sense of a belief that different historical eras have fundamentally different modes of social interaction.

Both views had some historical precedent (for instance historicism is clearly evident in the writings of Machiavelli and Montesquieu), but it’s their combination that’s particularly explosive, and Rousseau is the first person to place the two elements together and thereby assemble a bomb. Because for Rousseau, unlike for any of the ancient or medieval philosophers, merely to be a member of the human species does not automatically mean you’re living a fully-human life. But if humanity is something you can grow into, then it’s also something that you can be prevented from growing into. Thus: “that I am not a better person becomes for Rousseau a grievance against the political order. Modern institutions have deformed me. They have made me the weak and miserable creature that I am.”

But what if the qualities of social interaction which have this dehumanizing effect are inextricably bound up with the dominant spirit of the age? In that case, it might be impossible to really live, impossible to produce happy and well-adjusted human beings, without a total overhaul of society and all of its institutions. This also clarifies how the longing for total revolution is distinct from utopianism — utopian literature is motivated by a vision of a better or more just order. Revolutionary longing springs from a hatred of existing institutions and what they’ve done to us. This is an important difference, because hate is a much more powerful motivator than hope. In fact Yack goes so far as to say (in a wonderfully dark passage) that the key action of philosophers and intellectuals upon history is the invention of new things to hate. Can you believe this guy is Canadian?

1. Of course, if my reading of MITI and the Japanese Miracle is correct, popular sovereignty may not be around for that much longer.

2. I say “vulgar” Marxists, because for the sophisticated Marxists (including Marx himself) it’s already pretty much dogma that premodern rebellions by immiserated peasants aren’t “revolutionary” in the way they care about.

May 28, 2023

QotD: Karl Marx and the “excess labour” problem

In short: If you want to know what kind of society you’re going to have, look at labor mobility.

This is not to say that slavery is the only answer. There are lots of ways to absorb excess labor. Ever gone shopping in the Third World? There’s one guy who greets you at the door. Another guy follows you around the store, helpfully suggesting items to buy. A third guy rings up your purchases, which are packed up by a fourth guy, and a fifth guy carries them out (or arranges delivery by a sixth guy). And none of those guys are actually the shopkeeper. They’re all his cousins and whatnot, fresh from the sticks, and all of them are working four jobs with four other uncles at different places in the city.

Nor is it just a Third World thing. Basic College Girls love that Downton Abbey show, so I’d use that to illustrate the point if BCGs were capable of comprehending metaphors. George Orwell wrote eloquently about growing up on the very ragged edge of “respectability” at the turn of the century. He knew all about servants, he said, and the elaborate codes of conduct in dealing with them, even though his family could afford only one part-time helper. Your real toffs, of course, had battalions of servants to do every conceivable job for them. What else is that, old bean, but an elegant solution to labor oversupply?

Note also, since I’m giving you very basic Marxist history here, that we’ve just discovered the foundations of Feminism. Though Karl Marx was — of course — a total asshole to both his wife and his domestic help (of course he had “help”; the tradition of using and abusing servants while bemoaning the plight of the proletariat comes straight from the Master himself), he realized that his theories had a hard time accounting for the very real economic effects of domestic labor. Hence Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, which proves that even lemon-faced termagants with three degrees and six cats pulling down $100K per year shrieking about Feminism are MOPEs. You can cut the labor supply in half by shackling single gals to the Kinder, Küche, Kirche treadmill.

Severian, “Excess Labor”, Rotten Chestnuts<, 2020-07-28.

May 20, 2023

QotD: Alienation

One of Marx’s most famous concepts, “alienation” initially meant “the systemic separation of a worker from the product of his labor”. The result of a craftsman’s labor is directly visible beneath his hands, growing by the day; when he’s done, the shirt (or whatever) sits there before him, fully finished. The factory worker, by contrast, is little more than a machine-tender; he pulls the lever, and the finished article is squirted out somewhere far down the line, automatically, by machine. His “labor” consists of lever-pulling and jam-clearing.

It was a real enough insight into the psychology of factory work, and Marx deserves all the credit he got for it, but “alienation” was even more useful in a broad social context — the separation of man from the cultural products of his society. After all, if capitalism is the mode of production around which society organizes itself, and the products of capitalism are by definition alienated from their producers, then by extension capitalist society must be alienated from itself. Indeed, what could “society” even mean, in a world of lever-pullers and bearing-lubers and jam-clearers?

Again, a profound and important insight into the social conditions of the Industrial Age. Ours is a mechanical, transactional world, one not well-suited to the kind of organism we are. That’s why Marxism and its spacey little brother Nazism are both what Jeffrey Herf calls “reactionary modernism.” The Communists thought they were the endpoint of the Enlightenment; the Nazis rejected it entirely; but both of them were curdled Romantics, in love with Enlightenment science while terrified of that science’s society. Lenin said that Communism was “Soviet power plus electrification”. Goebbels wasn’t that pithy, but “the feudal system plus autobahns” is pretty much what he meant by Nazism, and both boil down to “medieval peasant villages with air conditioning”.

That the one excludes the other — necessarily, comrade, necessarily, in the full Hegelian sense of the word — never occurred to either of them shouldn’t really be held against them, since both of them were determined to freeze the world exactly as it was. Both were so terrified of individuality that they were determined to stamp it out, not realizing that individuality was the only thing that made their fantasy worlds possible. Medieval peasants who were happy being medieval peasants never would’ve invented air conditioning in the first place, nicht wahr?

Severian, “Alienation”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-29.