One of the predictions I’m seeing everywhere, for instance, is how now Human Resources will need a lot more power over companies to prevent more #metoo incidents of sexual importuning of women.

The funny thing about this is that anyone with two eyes and a modicum of understanding of the world knows that this is not where the crazy is headed. As the attempt to drown out the legitimate cases of harassment — mostly by leftists, in leftist-dominated institutions — by claiming #metoo and that all men were essentially harassers becomes more frantic, it has become obvious that any man can be accused of harassment at any time by anyone.

So, here is a genuine prediction: I predict that instead of giving HR more power, this will give companies pause before hiring women, which will lead to a lot of decent and qualified women being left unemployed.

The second-order effect of that, for companies that can’t avoid hiring women, is two-fold: they’ll either hire women to “make-believe” positions, in which they interact only or primarily with other women, creating a drain on the bottom line, or they will allow a lot more work-at-home by both men and women. I predict we’ll see a great move towards that in the next year. Sure, it’s still possible to claim someone is harassing you via the phone, but one-party consent states at least will allow men to record everything in order to defend themselves.

Weirdly, I believe the long-term result of this will be the dismantling of the daycare and child-warehousing practice which has led to a lot of the left’s ascendency in education.

This is because no matter how much you wish to wishful think that companies will just give Human Resources more power, people who actually live and work in the world know this isn’t likely. Human Resources would mostly just make it impossible for anyone to get any work done.

Sarah Hoyt, “Nobody Expects These Predictions”, PJ Media, 2017-12-31.

March 16, 2020

QotD: Company incentives to prevent sexual harassment

March 9, 2020

One of the economic effects of the Coronavirus outbreak might actually be bottom-line positive

Tim Worstall explains:

“Trade Show Portfolio – Guy Lewis Photography” by Guy Lewis is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

One notable thing about tech events is that they tend to be in interesting places like Amsterdam and Barcelona, and you don’t get many self-employed attending. Because someone self-employed loses days of paid hours, has to pay for the flights and the tickets. And they can get the same stuff from YouTube or various learning sites like Lynda.com. Tech events are mostly a jolly for employees in bloated companies. You get 3 days out of the office, have some fun and the boss picks up the tab. Losing this will probably improve the bottom line. And “business conferences” are mostly the same.

For people working more from home, that’s a good thing. Reduced travel costs (time and petrol), less tiredness. This is gradually happening anyway, but Coronavirus has given it a boost.

And maybe everyone realises that a system of education inherited from the time before Gutenberg, when books were a scarce resource, is perhaps in need of reform. OK, you probably need to be at a university for cutting up cadavers in medicine, but for history or computer science you can probably do most of it from your parent’s spare room.

One thing about the way people work is that they often fall into habits. Change often comes from startups and small businesses because they don’t have habits. Sometimes, they’re even anti-habit. Someone in a large company sees something as wasteful and scraps it in the new company. Microsoft let their people wear what they wanted for work, rather than suits. And gradually, those new businesses replace the old. But there’s also sometimes crises that break habits. Someone is forced to do something and gets their eyes opened. They perhaps realise that the alternative works fine, or maybe better.

March 5, 2020

Chain Your Woman to the Stove – Feminism in the 1930s | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1938 Part 2 of 4

TimeGhost History

Published 4 Mar 2020Under the yoke of economic depression and more and more authoritarian rulers, Western women face renewed misogyny, patriarchy, and decreasing independence. But not all women think this is such a bad thing.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Spartacus Olsson

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Spartacus Olsson

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiSources:

Bundesarchiv_Bild:

101III-Alber-174-14A, 102-04517A, 102-17313, 102-17818,

111-098-069, 137-055879, 146-1973-010-31, 146-1975-069-35,

146-1976-112-03A, 146-2006-205, 146-2008-0271,

183-2000-0110-500, 183-2005-0502-502, 183-2005-0530-500,

183-E10868, 183-E20457, 183-H28245, 183-J02040,

183-S08630, 183-S68014, 183-S68021, 183-S68029,

noun_pipe By Icon Lauk,

noun_company By wardehpillai,

noun_Farmer By Francisca Muñoz Colina.Colorizations by:

– Daniel Weiss

– Norman StewartSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “Sophisticated Gentlemen” – Golden Age Radio

– “The Inspector 4” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Magnificent March 3” – Johannes Bornlöf

– “Last Point of Safe Return” – Fabien Tell

– “Step On It 5” – Magnus Ringblom

– “First Responders” – Skrya

– “Step Lightly” – Farrell Wooten

– “Try and Catch Us Now” – David Celeste

– “Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar Johnsen

– “The Dominion” – Bonnie Grace

– “The Charleston 3” – Håkan ErikssonA TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago (edited)

So, we take a little break from the geopolitical developments in 1938 to look at the situation of women in the Western World in 1938. We’ve received a lot of requests on the WW2 channel to cover the situation on the home fronts. While we do mention it in the weekly episodes, and War Against Humanity covers the horrid parts of it, WWII was so much more. It literally changed the world’s culture in just six years. To do that subject justice we have asked Anna to join us as host for a new monthly WW2 series: On the Homefront.A few years back Anna was a regular feature on German YouTube on her own channel and some of the bigger YouTube entertainment channels. She left YouTube to finish her studies, and because she was searching for more depth than YT entertainment content was offering her. As Astrid’s and my daughter, and having grown up with Indy around all the time, she has a passion for human history form childhood, especially cultural history.

She also has a personal relationship to this time through her grandparents, Herbert and Renate, Astrid’s parents who served in Germany during the war, on the front and at home. Herbert, a career administrator and later NCO in the Wehrmacht engineer corps, went on after the war to work for the British as translator, and then as a public servant supporting the creation of the Bundeswehr, the German defense forces, and eventually Germany’s contribution as NATO member.

Renate’s father, a bank director, died under mysterious circumstance in 1936 after repeatedly refusing to pay out money belonging to Jewish families to the Nazis. Her mother and sisters soldiered on under the Nazis as best they could, When the war broke out they first suffered under the Allied bombing, losing their home three times. When the bombing became a daily occurrence, Renate was drafted to the German flak and only barely survived the war.

Several years after the war Herbert and Renate met and started a family together. They both passed away only a few years ago, late enough so that Anna had a chance to spend countless hours over 23 years listening to their war stories, and what they took away from it: hope for a better world, and the knowledge that what happened in Germany between 1933 and 1945, must never happen again. Please join us to welcome Anna, our daughter to TimeGhost.

Spartacus

February 21, 2020

British wages to be further impacted by Brexit

As we were told for years, if Brexit happened there were going to be dire consequences to the British economy, and here’s the latest one:

Employers are complaining that without badly paid immigrant labour they’ll just not be able to get the staff. The answer to which is that they’d better start paying higher wages then, eh?

[…]

The analysis here stems from something Marx got right. It’s competition among capitalists for scarce labour which pushes wages up. If there’s a vast reserve army of the unemployed then anyone needing more straining backs just tosses a crust to those in that army and gets as many limbs and torsos to exploit as desired. But if all are already employed then any desire for extra labour requires tempting it away from current employer and occupation to the new. That means a better job offer. Some mixture of conditions, enjoyment of the job, cash and so on that makes up a more attractive package.

The combination of cheap flights and free movement of labour has meant that the reserve army lives in Wroclaw and Debrecen. It’s also been near unlimited – compared to the size of the UK economy – these past couple of decades.

The absence of free movement – what is being complained about here – will mean that to gain the desired labour those employers are going to have to offer higher wages, higher compensation rather, to those not ordinarily resident or stemming from central Europe.

[…]

But back to the basic complaint here. These employers are complaining that Brexit will mean they’ve got to raise the wages they pay. To which the correct response is “Ah, Diddums”.

February 10, 2020

QotD: Welfare programs as a form of subsidy to employers

A final line of argument is that these public assistance programs have become de facto subsidies for low-wage employers. For a program to be a subsidy for an employer, it needs to lower wages. Is this plausible for the public assistance programs considered? I think it is for the EITC [Earned Income Tax Credit], but not for other programs. Depending on where one is on the EITC schedule, that policy can increase work incentives. And there is a lot of empirical evidence showing EITC encourages labor force participation. An unintended consequence of that labor supply response, however, is that employers capture some of the tax subsidies. This can happen in a simple supply and demand framework, where an increased labor supply to the market drive wages down. This can also happen in a bargaining context where the size of the bilateral surplus expands from lower taxes, and employers capture some of this increased surplus. Work by UC Berkeley’s Jesse Rothstein suggests that for every $1 of transfer to workers using the EITC, post-tax income rises only by $0.73 because of employer capture.

But what about other programs like food stamps or housing assistance? These means tested public assistance programs are not tied to work, and we should not expect them to lower wages. Let’s take food stamps, which are available to eligible families whether or not a family member works or not. Indeed, when people are not working, they are more likely to be eligible for food stamps since their family incomes will be lower. Therefore, SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program] is likely to raise, and not lower a worker’s reservation wages — the fallback position if she loses her job. This will tend to contract labor supply (or improve a worker’s bargaining position), putting an upward pressure on the wage. Whether or not wages are increased is an empirical matter: there is evidence that the initial roll-out of the food stamps program across counties in the 1970s lowered work hours, consistent with an increase in the reservation wage. The key point is that it is difficult to imagine how food stamps would lower wages. And if they don’t lower wages, they can’t be thought of as subsidies to low wage employers. The same logic applies to other means tested programs like energy or housing assistance. Moreover, these conclusions hold in a wide array of models of the labor market, including ones that emphasize bargaining or efficiency wage concerns.

Arindrajit Dube, “Public Assistance, Private Subsidies and Low Wage Jobs”, Arindrajit Dube, 2015-04-19.

January 24, 2020

QotD: Writing as a career

Leftist writers raised in affluent circumstances — as I think even they would admit, in honest moments — suffer from heroic self-image as an occupational disease. And perhaps this is equally true of the conservatives as well. But when you come from the actual working class — when your father is someone who actually helps assemble buildings, as opposed to designing them — you can never, as a professional intellectual, shake the suspicion that you are going to get caught and sent back to [earn] a proper living. I think it’s part of why relatively minor career crises have such a shattering effect on my nerves; as a columnist I’ve turned out to be much more of a cowardly beggar for editorial reassurance than I ever thought I’d be. It’s because I see my career subconsciously, and always will, as the product of some inchoate power’s inexplicable carelessness.

Colby Cosh “Who let him in?”, ColbyCosh.com, 2005-01-19.

November 1, 2019

QotD: The much-ballyhoo’d open office benefits are a lie

As urban rents crept up and the economy reached full employment over the last decade, American offices got more and more stuffed. On average, workers now get about 194 square feet of office space per person, down about 8 percent since 2009, according to a report by the real estate firm Cushman & Wakefield. WeWork has been accelerating the trend. At its newest offices, the company can more than double the density of most other offices, giving each worker less than 50 square feet of space.

As a socially anxious introvert with a lot of bespoke workplace rituals (I can’t write without aromatherapy), I used to think I was simply a weirdo for finding modern offices insufferable. I’ve been working from my cozy home office for more than a decade, and now, when I go to the Times‘ headquarters in New York — where, for financial reasons, desks were recently converted from cubicles into open office benches — I cannot for the life of me get anything done.

But after chatting with colleagues, I realized it’s not just me, and not just the Times: Modern offices aren’t designed for deep work. […]

The scourge of open offices is not a new subject for ranting. Open offices were sold to workers as a boon to collaboration — liberated from barriers, stuffed in like sardines, people would chat more and, supposedly, come up with lots of brilliant new ideas. Yet study after study has shown open offices to foster seclusion more than innovation; in order to combat noise, the loss of privacy and the sense of being watched, people in an open office put on headphones, talk less, and feel terrible.

Farhad Manjoo, “Open Offices Are a Capitalist Dead End”, New York Times, 2019-09-25.

September 3, 2019

When “raising awareness” works too well

Dylan Gibbons reports on a recent finding from the Harvard Business Review:

A new study published by the Harvard Business Review shows that in addition to men’s growing fears about women in the workforce and potentially being falsely accused, women are becoming more aware of the backlash and are actually less likely to hire certain women, specifically attractive women.

“Most of the reaction to #MeToo was celebratory; it assumed women were really going to benefit,” said Leanne Atwater, a management professor at the University of Houston. However, Atwater was skeptical. Rather than seeing an endless trail of steps forward before her, she and her colleagues forecasted a backlash.

“We said, ‘We aren’t sure this is going to go as positively as people think — there may be some fallout.'” And so, they tested their hypothesis.

The study began in early 2018. Two surveys were created, one for men and one for women. These surveys were then distributed to workers in various professional fields. In the end, they collected a large amount of data from 152 male and 303 female responders.

According to the study, 74% of women now say they are more willing now to speak out against harassment, while 77% of men anticipated being more careful about potentially inappropriate behaviour.

As for the idea that men do not know what constitutes harassment, the researchers found the opposite was true. Both genders appear to both know what constitutes harassment, and women may be more lenient with some of their own definitions of what constitutes harassment.

According to the report, “The surveys described 19 behaviors — for instance, continuing to ask a female subordinate out after she has said no, emailing sexual jokes to a female subordinate, and commenting on a female subordinate’s looks — and asked people whether they amounted to harassment.”

“Most men know what sexual harassment is, and most women know what it is,” Atwater says. “The idea that men don’t know their behavior is bad and that women are making a mountain out of a molehill is largely untrue. If anything, women are more lenient in defining harassment.”

Another recent action intended to increase the number of women in STEM subjects at an Australian university — by selectively lowering academic standards for admission — will almost certainly not achieve its stated goals, but will work to increase negative views of those women in the working world:

[A female engineer] also rightly points out that this lowering the bar for women is unfair to men losing the university places to women with lesser qualifications.

She points out that male students will notice that women are struggling more with the course material — the women allowed in because the bar was lowered.

She feels this is a net negative for women in the engineering sector in general, and I have to agree.

How, she asks, can employers be expected to see a woman’s engineering degree the same as a man’s if the employer knows the women got a break getting into the program?

She uses the term “positive discrimination” to describe the leg-up practices, and I really prefer that to “affirmative action” to describe it because the word “discrimination” is plain in it. And that’s exactly what it is. Discrimination against qualified people that will ultimately harm women who are qualified.

As she puts it, the only way to ensure that a woman’s qualifications mean as much as a man’s is to have equal hurdles for women.

I’m completely with her.

August 24, 2019

QotD: Strikes at non-profit organizations

The usual argument in favour of union power and the right to strike and so on is that the workers have to be able to band together to beat back the concentrated power of the capitalists. I’m all in favour of the freedom of association, considering it just as important as the freedom of speech so unions themselves hold no terrors for me. But that standard case that labour must be protected, protect itself perhaps, from the profit gouging activities of the owners rather fails when there are no profits, are no owners trying to maximise them as they grind the workers into the dust. Which is what we see here at National Public Radio. There’s the threat of a strike in the air and yes, it’s about pay scales. But there just aren’t any greedy plutocrats to take the cash from, nor are there any taking anything at present. Thus we see the finances of an organisation in a rather more stark manner.

[…]

Which is where we get to see the pay deal matter in the raw. At the auto companies (well, absent those in and near bankruptcy problems) it was indeed possible to start shouting “But what about the workers?” Why should they get less generous pay or terms just so that the capitalists can make out like bandits? But here we’ve got exactly the same problem. And there are no capitalists, there are no profits. The income into NPR is pretty much exclusively used to pay the employees of NPR. There are no leakages to the capitalists so, in the absence of more money, what can be done?

[…]

You can see NPR’s finances here and it becomes obvious that they have available only two of the traditional three ways of dealing with a higher wage bill. In for profit companies there is that possibility of reducing the profit to pay the workers more. In the absence of profiteering this cannot of course happen. Thus, in order to accommodate higher wages they can either raise prices to stations which carry the programs or NPR can employ fewer people at those higher wages. They’re restricted to only two of those ways normally put forward. Something which does rather aid in highlighting why and how companies, for profit ones, react the way they do to forced pay rises.

That NPR is a non-profit aids in highlighting exactly the problems that all organisations have with demands for higher wages. With no profits to cut they can either charge more or employ fewer people, nothing else.

Tim Worstall, “NPR’s Problems – Isn’t It Fun When Workers At A Non-Profit Seek To Strike?”, Forbes, 2017-07-15.

July 6, 2019

Putting global worker pay into perspective

Tim Worstall explains why the headline-friendly numbers in a recent ILO report are nothing to be surprised at:

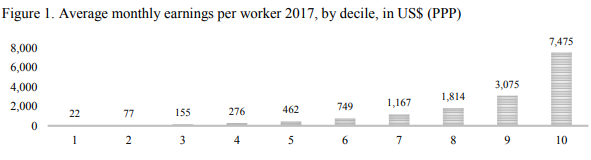

“Nearly half of all global pay is scooped up by only 10% of workers, according to the International Labour Organization, while the lowest-paid 50% receive only 6.4%.

“The lowest-paid 20% – about 650 million workers – get less than 1% of total pay, a figure that has barely moved in 13 years, ILO analysis found. It used labour income figures from 189 countries between 2004 and 2017, the latest available data.

“A worker in the top 10% receives $7,445 a month (£5,866), while a worker in the bottom 10% gets only $22. The average pay of the bottom half of the world’s workers is $198 a month.”

[…]

The explanation? To be in the top 10% of the global pay distribution you need to be making around and about minimum wage in one of the rich countries. Via another calculation route, perhaps median income in those rich countries. No, that £5,800 is the average of all the top 10%.

Note that this is in USD. About £2,000 a month puts you in the second decile, that’s about UK median income of 24,000 a year.

And as it happens about 20% of the people around the world are in one of the already rich countries. So, above median in a rich country and we’re there. Our definition of rich here not quite extending as far as all of the OECD countries even. Western Europe – plus offshoots like Oz and NZ, North America, Japan, S. Korea and, well, there’s not much else. Sure, it’s not exactly 10% of the people there but it’s not hugely off either.

So, what is it that these places have in common? They’ve been largely free market, largely capitalist, economies for more than a few decades. The most recent arrival, S. Korea, only just managing that few decades. It is also true that nowhere that hasn’t been such is in that listing. It’s even true that nowhere that is such hasn’t made it – not that we’d go to the wall for that last insistence although it’s difficult to think of places that breach that condition.

June 10, 2019

QotD: Robert Heinlein on “honest work”

The beginning of 1939 found me flat broke following a disastrous political campaign (I ran a strong second best, but in politics there are no prizes for place or show).

I was highly skilled in ordnance, gunnery, and fire control for Naval vessels, a skill for which there was no demand ashore — and I had a piece of paper from the Secretary of the Navy telling me that I was a waste of space — “totally and permanently disabled” was the phraseology. I “owned” a heavily-mortgaged house.

About then Thrilling Wonder Stories ran a house ad reading (more or less):

GIANT PRIZE CONTEST —

Amateur Writers!!!!!!

First Prize $50 Fifty Dollars $50In 1939 one could fill three station wagons with fifty dollars worth of groceries.

Today I can pick up fifty dollars in groceries unassisted — perhaps I’ve grown stronger.

So I wrote the story “Life-Line.” It took me four days — I am a slow typist. I did not send it to Thrilling Wonder; I sent it to Astounding, figuring they would not be so swamped with amateur short stories.

Astounding bought it… for $70, or $20 more than that “Grand Prize” — and there was never a chance that I would ever again look for honest work.

(“Honest work” — an euphemism for underpaid bodily exertion, done standing up or on your knees, often in bad weather or other nasty circumstances, and frequently involving shovels, picks, hoes, assembly lines, tractors, and unsympathetic supervisors. It has never appealed to me. Sitting at a typewriter in a nice warm room, with no boss, cannot possibly be described as “honest work.”)

Robert A. Heinlein, 1980.

June 6, 2019

New paper on minimum wage effects is bound to be mis-used

In the Washington Examiner, Tim Worstall explains why a new well-researched paper on the minimum wage will be misunderstood and then used to “prove” things it doesn’t actually say:

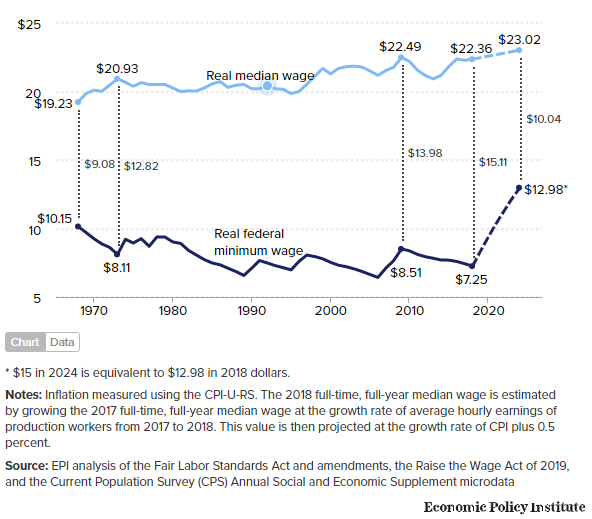

None of this changes the standard intuition that when there’s a heavy such bite then there will be ill effects. What it does do is then lead us to trying to calculate what is a wage that does have that snarl, that bite? What is a minimum wage that is “too high” in the sense of having an excess of those ill effects upon employment? This is where I predict — no, not fear, not posit, nor surmise, but predict — this paper will be misused.

Our thinking is that the effects come from the relationship between the minimum and median wages. If we insist that wages cannot be lower than more than we already pay half the people, then we really are going to have problems. A minimum wage of 100% of the median wage isn’t going to work, that is. That ratio is called the Kaitz Index. This paper shows us that there are few to no such bad things happening up to 0.59 on that Kaitz measure. We can have the minimum wage at 59% of the median wage and know that we’ll have the good effects and only trivial amounts, at worst, of the bad.

You can see what’s going to happen next, can’t you? The Economic Policy Institute tells us that the median wage is about $22 this year, and 59% of that is $13. A bit of rounding and some aspiration, and why not go for a $15 minimum wage?

Except there are two median wages. Part-time and seasonal wages tend to be lower than full-year and full-time ones. The Economic Policy Institute is using that higher full-time one. The one for all jobs is quite a bit lower, $18.58 per hour. Take 59% of that and you get a rather lower level of $10.95 an hour. That’s around and about what McDonald’s, Walmart, and similar establishments pay as entry-level wages, which does seem about right, doesn’t it?

So, the new research paper, from esteemed researchers, published in the world’s top English language economics journal, tells us that minimum wages up to a certain level cause few to no problems. They’ve shown this for up to 59% of median wages. But which median do they mean? Dube himself told me they mean that lower one — specifically, the “median wage of all workers, not just for full time.”

But we all know how this is going to be used, don’t we? As proof that $15 an hour won’t cause any problems — which isn’t what the paper shows at all. Rather, it says that a $10.95 an hour minimum wage shouldn’t cause any problems of note.

The new paper is good empirical work. The fault is in what people will argue it says, not what it does.

June 3, 2019

The state of US academia in juxtaposed tweets

American universities have problems, but the solutions they choose do not seem to be addressing those problems (screencapped, in case the tweet doesn’t load correctly):

May 23, 2019

Game of Theories: The Keynesians

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 7 Nov 2017When the economy is going through a recession, what should be done to ease the pain? And why do recessions happen in the first place? We’ll take a look at one of four major economic theories to find possible answers – and show why no theory provides a silver bullet.

May 12, 2019

Mechanisms for redressing employment gender imbalances

We’ve often been told that too many men occupy positions of power and influence in the working world, but what would it take to meaningfully address those imbalances?

Equity … is based on the idea that the only certain measure of “equality” is outcome — educational, social, and occupational. The equity-pushers axiomatically assume that if all positions at every level of hierarchy in every organization are not occupied by a proportion of the population that is precisely equivalent to that proportion in the general population that systematic prejudice (racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.) must be at play. This assumption has as its corollary the idea that there are perpetrators (the “privileged,” for current or historical reasons) who are unfair beneficiaries of the system or outright perpetrators of prejudice and who must be identified, limited and punished.

[…]

Now it doesn’t seem like mere imagination on my part that all the noise about “patriarchal domination” is not directed at the fact that far more men than women occupy what are essentially trade positions. Nor does it seem unreasonable to point out that these are not particularly high-status jobs, although they may pay comparative well. It is also obvious that none of these occupations and their hierarchies, in isolation, can be thoughtfully considered the kind of oppressive patriarchy supposed to constitute the “West,” and aimed at the domination and exclusion of women. By contrast, the trade occupations are composed of cadres of working men, with difficult and admirable jobs, who keep the staggeringly complex, reliable and essentially miraculous infrastructure of our society functioning through rain and snow and heat and gloom of night and who should be credited gratefully with exactly that.

Let’s assume for a moment that we should aim at equity, nonetheless, and then actually think through what policies would inevitably have to be put in place to establish such a goal. We might begin by eliminating pay scales that differ (hypothetically) by gender. This would mean introducing legislation requiring companies to rank-order their sex representation at each level of the company hierarchy, adjust that to 50:50, and then adjust the pay differential by gender at every rank, so that the desired equity was achieved. Companies could be monitored over a five-year period for improvement. Failure to meet the appropriate targets would be necessarily met with fines for discrimination. In the extreme, it might be necessary to introduce staggered layoffs of men so that the gender equity requirements could be met.

Then there are the much broader social policy implications. We could start by addressing the hypothetical problems with college, university and trade school training. Many companies, compelled to move rapidly toward gender equilibria, will object (and validly) that there are simply not enough qualified female candidates to go around. Changing this would mean implementing radical and rapid changes in the post-secondary education system, implemented in a manner both immediate and draconian — justified by the obvious “fact” that the reason the pipeline problem exists is the absolutely pervasive sexism that characterizes all the programs that train such workers (and the catastrophic and prejudicial failure of the education system that is thereby implied).

The most likely solution — and the one most likely to be attractive to those who believe in such sexism — would be to establish strict quota systems in the relevant institutions to invite and incentivize more female participants, once again in proportion to the disequilibria in enrollment rates. If quotas are not enough, then a system of scholarship or, more radically (and perhaps more fairly) women could be simply paid to enroll in education systems where their sex is badly under-represented. Alternatively, perhaps, men could be asked to pay higher rates of tuition, in some proportion to their over-representation, and the excess used to subsidize the costs of under-represented females.