Forgotten Weapons

Published 1 Dec 2019In 1884, Hugh Silver and Walther Fletcher patented a system to rapidly unload a gate-style revolver. They negotiated an agreement to have their system integrated into Webley revolvers (specifically the New Model RIC) as an option, and sold about 350 of them, including some to both the Royal Irish Constabulary and the Metropolitan London Police, under the name “The Expert”. Not so different from today’s tactical widget market, eh? The practical use of the system was to bypass the glacially-slow manual ejector rod and instead unload a cylinder full of empty cases simply by pulling the trigger six times in rapid succession. To avoid the obvious potential safety hazard this entailed, they also added a safety to retract the firing pin. It’s this firing pin safety that people usually notice when seeing the guns, as it is much more visible than the ejection mechanism.

The system could also be used to eject empty cases one by one as the gun was fired, although doing so required leaving the loading gate open while firing. The Webley revolvers made with the system are devoid of Webley company markings, although they do have both a Webley serial number (most being in the 33,000 – 36,000 range) and a Silver & Fletcher number (between 1 and about 350).

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85704

April 2, 2020

1884 Tacticool: Silver & Fletcher’s “Expert” Auto-Ejector

April 1, 2020

Curator’s Tank Museum Tour: Tank Story Hall – WW1 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 31 Mar 2020Join Curator David Willey as he takes you on a tour of The Tank Museum’s Tank Story Hall, which houses over 30 key vehicles from Little Willie to Challenger 2. In this section he looks at the First World War vehicles and gives you a potted history of WW1.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Visit The Tank Museum SHOP & become a Friend: ► https://tankmuseumshop.org/Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Instagram: ► https://www.instagram.com/tankmuseum/

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/

#tankmuseum #tanks

March 24, 2020

Thompson 1921: The Original Chicago Typewriter

Forgotten Weapons

Published 6 Oct 2018https://www.forgottenweapons.com/thom…

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

The first prototype Thompsons submachine guns (and it was Thompson who coined that term, by the way) were produced in 1919 and dubbed the “Annihilators”. The gun was intended to be a military weapon to equip American soldiers in World War One, but by the time the gun was developed the war had ended. Still, Thompson and his Auto-Ordnance company contracted with Colt to manufacture 15,000 of the guns. These were the Model of 1921, and they were marketed to both the US military and as many European armies as Thompson and his salesmen could reach. They found few takers in the climate of the early 1920s, however, and sales were slow.

This is the first in a 5-part series about the development of the Thompson, concluding with a trip to the range to fire three different patterns side by side…

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

March 10, 2020

Thought-saving inventions

In the latest issue of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the innovations that helped provide short-cuts for thought, rather than labour:

The world on Mercator projection between 85°3’4″S and 85°3’4″N, such that image is square. 15° graticule. Imagery is a derivative of NASA’s Blue Marble summer month composite with oceans lightened to enhance legibility and contrast. Image created with the Geocart map projection software.

Image by Strebe via Wikimedia Commons.

When we think of labour-saving inventions, the kind of labour that springs to mind tends to be manual. We think of machines replacing the muscle of limbs and the dexterity of fingers, and we worry about their effects on unemployment and unrest. But there’s a subset of labour-saving inventions that rarely gets discussed. They might best be called thought-saving.

A few weeks ago I mentioned the introduction of mathematical techniques to navigation. Before the mid-sixteenth century in England, pilots very rarely even knew how to calculate their latitude, let alone their longitude. But over the course of just a few decades, England became one of the world leaders in navigational improvements. A handful of mathematicians saved pilots the trouble of calculation, by coming up with tables, instruments, diagrams, and rules of thumb. In the process, they improved navigation’s accuracy, and ushered in an age of English dominance of the high seas.

The historian Eric H. Ash gives a few great examples. In the 1590s, the explorer John Davis shared a way to calculate the time of high tide, without requiring multiplication. Likewise, William Bourne, a self-taught mathematician and gunner, in the 1560s provided an easy means of calculating the linear distance in one degree of longitude, at any given latitude. He provided a diagram — really an instrument, even if it wasn’t made of wood or brass — which with just a simple piece of string could be used to derive the answer without needing to understand cosines, or really any trigonometry.

The mathematicians did the same with maps, too (after all, aren’t all maps thought-saving?) The sixteenth-century cartographic innovations simplified the pilot’s ability to chart a route, for example by taking away all need to worry about the curvature of the earth. The famous 1560s map projection of Gerardus Mercator stretched the distance between the lines of latitude as they got closer to the poles, so that charting a course on such a map was a simple matter of drawing straight lines rather than complex trigonometry. The Mercator projection may well make Africa look smaller than Greenland — it’s actually almost fifteen times as large — but it made life significantly easier for mariners. For similar reasons, the mathematician John Dee designed a special chart — what he called the “paradoxall compass” — to aid the English explorers who in the 1550s went in search of a northeast and northwest passage to Asia. Conventional charts made navigating high latitudes confusing, as the north pole was a straight line — the map’s top border. Dee’s map made things easier by putting the pole at the centre, as a point, with the lines of latitude as concentric circles.

March 4, 2020

England’s Secret Weapon: The Two Million Ton Megacarrier Made of Ice

Today I Found Out

Published 16 Feb 2018If you happen to like our videos and have a few bucks to spare to support our efforts, check out our Patreon page where we’ve got a variety of perks for our Patrons, including Simon’s voice on your GPS and the ever requested Simon Whistler whistling package: https://www.patreon.com/TodayIFoundOut

This video is sponsored by World of Warships

In this video:

Britain was taking a beating from the German ships and submarines and were looking for something to build a ship out of that couldn’t be destroyed by torpedoes, or at least could take a major pounding without incurring a fatal amount of damage. With steel and aluminum in short supply, Allied scientists and engineers were encouraged to come up with alternative materials and weapons.

Want the text version?: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.p…

February 29, 2020

Forced-Air Cooling in an Experimental Ross Machine Gun

Forgotten Weapons

Published 28 Feb 2020http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

In addition to building three main patterns of straight-pull bolt action rifle for the Canadian military and the commercial market, Sir Charles Ross also experimented with self-loading rifles. Starting with a standard Ross Mk III, this experimental rifle has a gas piston and trigger to allow automatic fire and a very neat forced-air cooling system. A one-way ratchet mechanism (now broken, unfortunately) spins the fan when the bolt cycles, pushing air into a barrel shroud similar to that of a Lewis gun. This rifle was most likely made in 1915 or 1916 with an eye to a military light machine gun or automatic rifle contract — which never happened.

Thanks to the Canadian War Museum for providing me access to film this Ross for you!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

Dardick Model 1500: The Very Unusual Magazine-fed Revolver

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Nov 2019This is Lot 1953 in the upcoming RIA December Premier auction.

The Dardick 1500 was a magazine-fed revolver designed by David Dardick in the 1950s. His patent was granted in 1958, and somewhere between 40 and 100 of the guns were made in 1959, before the company went out of business in 1960. The concept was based around a triangular cartridge (a “tround”) and a 3-chambered, open-sided cylinder. This wasn’t really of direct benefit to a handgun, but instead was ideal for a high rate of fire machine gun, where the system did not need to pull rounds forward or backward to chamber and eject them. In lieu of military machine gun contract, Dardick applied the idea to a sidearm.

The Model 1500 held 15 rounds, inside a blind magazine in the grip. It was chambered for a .38 caliber cartridge basically the same as .38 Special ballistically. A compact Model 1100 was also made in a small numbers, with a shorter grip and correspondingly reduced magazine capacity (11 trounds). A carbine barrel/stock adapter was also made. The guns were a complete commercial failure, with low production and lots of functional problems. Today, of course, they are highly collectible because of that scarcity and their sheer mechanical weirdness.

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85704

I’ve always had an interest in the Dardick, from their appearance in some of L. Neil Smith’s science fiction novels. I linked to an earlier article of his, and commented:

As Neil pointed out in one of his books, the Dardick was the answer to a bad crime writer’s prayers: it was literally an automatic revolver. (For those following along at home, an “automatic” has a magazine holding the bullets which are fed into the chamber to be fired by the action of the weapon: fire a bullet, the action cycles, clearing the expended cartridge and pushing a new one into place, cocking the weapon to fire again. A “revolver” holds bullets in the cylinder, rotating the cylinder when the gun is fired to put a new bullet in line with the barrel to be fired. The Dardick is the only example I know of that combines both in one gun.)

February 28, 2020

“The Future of Warfare” – British Tanks of the Great War – Sabaton History 056 [Official]

Sabaton History

Published 27 Feb 2020Tanks! What a terrible and frightening sight they must have been for the Germans, the first time they had appeared on the battlefield at the Somme in 1916. The tanks were the product of many different ideas and prototypes, that all sought to overcome the perils of the modern battlefield — the machine gun, the bombed out ground and the barbed wire. The British Mark I tank would crush those obstacles through its sheer weight and begin a new age of mechanized warfare!

Support Sabaton History on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/sabatonhistory

Listen to “The Future of Warfare” on the album The Great War:

CD: http://nblast.de/SabatonTheGreatWar

Spotify: https://sabat.one/TheGreatWarSpotify

Apple Music: https://sabat.one/TheGreatWarAppleMusic

iTunes: https://sabat.one/TheGreatWarItunes

Amazon: https://sabat.one/TheGreatWarAmazon

Google Play: https://sabat.one/TheGreatWarGooglePlayWatch the official lyric video of “The Future of Warfare” here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t8qJi…Check out the trailer for Sabaton’s new album The Great War right here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCZP1…

Listen to Sabaton on Spotify: http://smarturl.it/SabatonSpotify

Official Sabaton Merchandise Shop: http://bit.ly/SabatonOfficialShopHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Directed by: Astrid Deinhard and Wieke Kapteijns

Produced by: Pär Sundström, Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Executive Producers: Pär Sundström, Joakim Broden, Tomas Sunmo, Indy Neidell, Astrid Deinhard, and Spartacus Olsson

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound Editing by: Marek Kaminski

Maps by: Eastory – https://www.youtube.com/c/eastoryArchive by: Reuters/Screenocean https://www.screenocean.com

Music by Sabaton.Sources:

– Bundesarchiv

– Bibliothèque nationale de France

– Library and Archives Canada

– National Library of Scotland

– Australian War Museum

– National Army Museum

– IWM: Q 53204, Q 115391, Q 1419, Q 78121, Q 72864, HU 55578, Q 14496, Q 14495, Q 2487, Q 2486, Q 5574, Q 52, Q 43463, Q 3565, Q 3542, Q 5578, Q 80026, Q 68975

– IWM ART: REPRO 000684 7

– Sound of tracktor engine by viertelnachvier, tank sound by nicstage, from freesound.orgAn OnLion Entertainment GmbH and Raging Beaver Publishing AB co-Production.

© Raging Beaver Publishing AB, 2019 – all rights reserved.

February 23, 2020

Chambers Flintlock Machine Gun from the 1700s

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Nov 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Joseph Chambers invented a repeating flintlock weapon in the 1790s, and I think it is appropriate to consider it a “machine gun”. The design used a series of superposed charges in one or more barrels, with specially designed bullets that has hollow central tubes through them. This would allow the fire from a detonation charge to transit through a bullet at the rear and set off a subsequent charge. The result was a single trigger pull to use a flintlock action to start an unstoppable series of shots. Chambers made pistol and musket versions, as well as a full-on mounted machine gun.

He submitted his design to the fledgling US War Department in 1792, but it was not accepted. He brought the guns back to their attention when the War of 1812 was declared, and this time he found an eager client in the United States Navy. More than 50 of the machine guns were built and purchased to use on Navy warships. This version had 7 barrels, each loaded with 32 rounds, for a total of 224 shots, at (apparently) about a 120 round/minute rate of fire. The British found out about the guns and made some effort to reverse engineer them, and there was also interest in France, the Netherlands, and Spain. Ultimately, the potential unreliability of the system prevented more widespread adoption, but the gun is a fascinating example of early automatic firearms.

For more information, see Andrew Fagal’s article:

https://ageofrevolutions.com/2016/10/…Thanks to the Liege Arms Museum for access to film this for you! If you are in Belgium, definitely plan to stop into the museum, part of the Grand Curtius. They have a very good selection of interesting and unusual arms on display.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle #36270

Tucson, AZ 85704

February 21, 2020

QotD: Thought experiment

If you were hovering above Earth looking to be born randomly into any time period in human history, you’d pick now if you had any brains. And if you could pick a place, you’d pick a Western liberal democracy, and probably the United States of America (though as much as it pains me to say it, you wouldn’t be crazy to pick Canada or the U.K. or Holland). Sure, if you could pick being rich, white, and male — and didn’t really care too much about the plight of others — you might take the 1950s. But even then, your choices for food, entertainment, etc. would be terribly curtailed compared to today. If you chose to be a billionaire in 1917, you could still die from a minor infection, and good Thai food would be entirely unknown to you. You’d certainly never enjoy watching a Star Wars movie on an IMAX screen in air conditioning. In other words, while your homes would be bigger and cooler if you were a billionaire in 1917, a typical orthodontist in Peoria in 2017 is in many respects much richer than a billionaire a century earlier.

Still, that’s not the deal on offer. You have to buy an incarnation lottery ticket, and the results would be random.

I’m not big on dividing people up by abstract categories, and I certainly don’t mean them to be pejorative. But as a historical matter, being born poor, gay, black, Jewish, ugly, weird, handicapped, etc. today may certainly come with some problems or challenges, but on the whole those traits are less of a shackle or barrier than at any time in the past. The only trait where I think it might be a closer call is dumbness. All other things being equal, a not-terribly-intelligent person with a good work ethic and some decent values might have had more opportunities before machines replaced strong backs. But even here, I can think of lots of exceptions.

Jonah Goldberg, “America and the ‘Original Position'”, National Review, 2017-12-22.

February 14, 2020

Innovation and the “low-hanging fruit”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes wonders about the “low-hanging fruit” theories on innovation and why some things that seem obvious in hindsight took so long to be noticed:

A theme I keep coming back to is that a lot of inventions could have been invented centuries, if not millennia, before they actually were. My favourite example is John Kay’s flying shuttle, one of the most famous inventions of the British Industrial Revolution. It radically increased the productivity of weaving in the 1730s, but involved simply attaching a little extra wood and string. It involved no new materials, was applied to the weaving of wool — England’s age-old industry — and required no special skill or science. Weaving had been “performed for upwards of five thousand years, by millions of skilled workmen, without any improvement being made to expedite the operation, until the year 1733”, was how Bennet Woodcroft — one of the nineteenth century’s most important historians of technology — put it. (Lest you doubt that description of Woodcroft, he was, in addition to being an inventor himself, the man who compiled and categorised England’s entire patent record up to 1852, and who collected the inventions that would later form the basis of London’s Science Museum, particularly some of the earliest steam engines — among the most important machines in human history — that grace its engine hall today. My hero!) Weavers had been around for millennia, as had shuttles: one is even mentioned in the Old Testament (“My days are swifter than a weaver’s shuttle, And are spent without hope”). As a labour-saving invention, Kay’s flying shuttle was even technically illegal.

I keep coming back to this example, because it goes against so many common notions about the causes of innovation. When it comes to skill, materials, science, institutions, or incentives, none of them quite seem to fit. But I keep seeing more and more such cases. There’s the classic example, of course, of suitcases with wheels — why so late? Was the bicycle another candidate?

It strikes me as odd, too, that there was an explosion of signalling systems like semaphore only towards the end of the eighteenth century. Although there were some seventeenth-century precursors, the main telegraphing systems in Europe seem to have been as crude as Gondor’s lighting of the beacons, capable only of communicating a single pre-agreed message. Ancient China at least had its smoke signals, as did many indigenous American societies, and apparently the ancient Greeks too. So what took semaphore so long to take off? Many of the eighteenth-century systems did not even need multicoloured flags, my favourite being Lieutenant James Spratt’s “homograph”, subtitled “every man a signal tower”, which involved just a long white handkerchief.

The economist Alex Tabarrok calls these cases “ideas behind their time“. I tend to just call them low-hanging fruit. Hanging so low, and for so long, that the fruit are fermenting on the ground. I now see them everywhere, not just in history, but today — probably at least one per week.

February 8, 2020

Confederate Whitworth Sniper: Hexagonal Bullets in 1860

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Oct 2017NOTE: Please see this video for a correction regarding Whitworth accuracy: https://youtu.be/cUd2RQGfL7E

Sold for $161,000.

Sir Joseph Whitworth is quite the famous name in engineering circles, credited with the development of such things as Whitworth threading (the first standardized thread pattern) and engineer’s blue. When he decided to make a rifle, he decided that he could make flat surfaces more precisely than round ones, and chose to design a rifle with a hexagonal bore and mechanically fitted bullets.

The Whitworth rifles proved to be magnificently accurate, with a British military test showing a group of 0.85 MOA at 500 yards, and under 8MOA even at 1800 yards. However, the rifles were equally expensive, and were not given further consideration for military use. Whitworth made a total of about 13,700, selling them to high level competitive marksmen and wealthy shooting enthusiasts. A small number were purchased by Confederate agents during the Civil War, and between 50 and 125 were able to evade the Union blockades to be delivered into Confederate hands. These rifles were equipped with Davidson 4-power telescopic sights, and they were put to extremely good effect by Confederate sharpshooting units. In particular, they were used to shoot at Union artillery crews, and Whitworth bullets have been found on a great many Civil War battlefields. They were not available in large numbers, but they were excellent rifles and put to use as much as possible.

Given the small number originally brought into the CSA, the number of known surviving examples is extremely low. This one, like many, was found without its scope and mount, and those parts have been replaced with period examples. As a true Confederate Whitworth, however, this is an extremely rare and historically relevant rifle!

http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

If you enjoy Forgotten Weapons, check out its sister channel, InRangeTV! http://www.youtube.com/InRangeTVShow

January 25, 2020

Refuting the pessimism of Malthus

In the latest edition of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention newsletter, he looks at the predictions of that old gloomy Gus, Thomas Malthus:

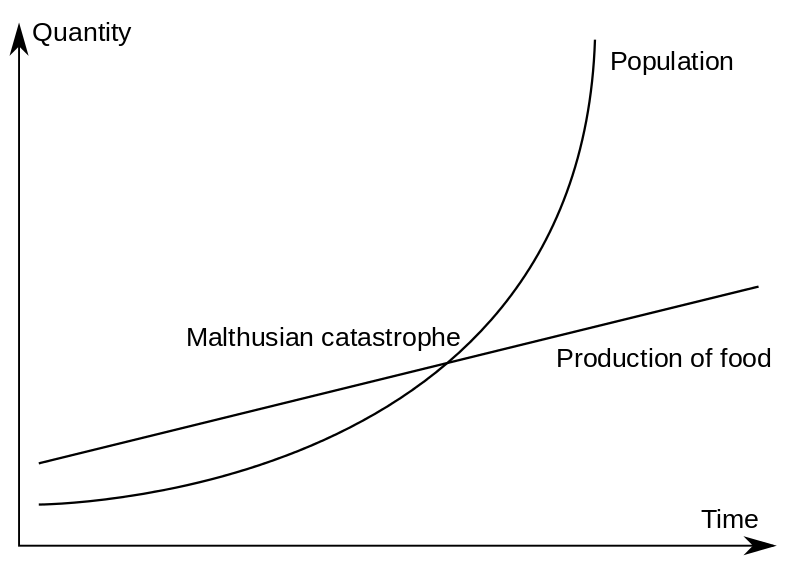

The Malthusian trap. For Malthus, as population increases exponentially and food production only linearly, a point where food supply is inadequate will inevitably be reached.

Graph by Kravietz via Wikimedia Commons.

For economies before the Industrial Revolution, population growth was an important and ever-present brake on prosperity — an observation most famously articulated by the Reverend Thomas Malthus. Writing at the end of the eighteenth century, he warned against the promises of improvement. Whereas the optimists looked at the acceleration of innovation around them and claimed infinite horizons for increasing living standards, Malthus pessimistically argued that population would always catch up. Although a new agricultural technology might briefly increase the amount of available food, the inexorability of population growth meant that it would soon be eaten up by extra mouths to feed. The population would end up larger than it was before the new technology, but with that population eventually no richer than it had been to begin with. Economic historians call this the Malthusian regime, or the Malthusian Trap.

Fortunately, Malthus’s pessimism would prove unfounded. Economy after economy has managed to escape the trap. British output had already been outpacing its population for two centuries by the time he was writing — England’s agricultural output alone had increased 171% while its population had grown 113% (not even taking into account the fact that it also increasingly relied on imported food, paid for by its other industries). And in the decades and centuries that followed, England’s output continued to shoot ahead, widening the lead. Output per capita rose and rose, to the extent that Malthus’s worries about overpopulation are now usually applied to resources other than food.

But while Malthus is famous for the theory, he wasn’t its inventor. Well before Malthus, the people who actually lived in the trap seem to have recognised its effects. Concerns about overpopulation may have led to the Garland or Flower Wars of the Aztec Empire and its neighbours: after a series of famines in the 1450s, the local states reportedly began to engage in ritual battles, with the losers captured and sacrificed to the gods. Still earlier, in ancient Greece, the young men of a settlement might be formally conscripted to go forth and colonise other islands and coastlines. They were typically banned from returning home for several years, and in at least one case slingers were posted on the shore to kill any of the colonists who tried to make a break for home. In a whole host of pre-industrial societies, “surplus” infants were often simply exposed to the elements.

By the sixteenth century, with the rise of print culture, Malthusian rationales were being clearly articulated. Here’s Richard Hakluyt writing in 1584, over two hundred years before Malthus:

Through our long peace and seldom sickness (two singular blessings of Almighty God) we are grown more populous than ever heretofore; so that now there are of every art and science so many, that they can hardly live one by another, nay rather they are ready to eat up one another.

It’s a direct statement of the Malthusian regime in action, expressed by one of England’s most influential Elizabethan intellectuals, and written specifically for the attention of the queen. Hakluyt thanked god for the recent and unusual lack of mass death, but now worried about overpopulation leading to low wages and unemployment. And he went on to list many other effects. Hakluyt argued that the misery would lead to unrest, thievery, begging, and “other lewdness”. The prisons filled up, where the poor either “pitifully pine away, or else at length are miserably hanged.”

January 22, 2020

Introduction to Military Flamethrowers with Charlie Hobson

Forgotten Weapons

Published 5 May 2016http://www.flamethrowerexpert.com

You can find Charlie Hobson’s book, US Portable Flamethrowers here:

http://amzn.to/1SP9yc5Flamethrowers are a significant piece of military weapons history which are very widely misunderstood, as flamethrowers have never been the subject of nearly as much collector interest as other types of small arms. The US military removed its flamethrowers from inventory in 1985, and all other major national militaries have done the same. In the US, the lack of general interest led to most of the surplussed weapons being destroyed as scrap, and few survive in private collections. At the same time (and for the same reason) a great deal of the information on these weapons was also discarded and lost.

One of the people who has done a tremendous amount of work to recover practical information on historical military flamethrowers as well as restore, service, and operate them is Charlie Hobson. He has worked extensively with the US military museum system as well as the entertainment industry (if you have seen a movie of TV show using a real flamethrower, it was almost certainly done under his supervision).

Today I am discussing the basic of flamethrowers with Charlie. The goal is to provide a good baseline foundation so we can go on to look at a couple specific historical flamethrowers and understand them in context. So sit back, relax, and enjoy a chat with a man who is truly passionate about this underappreciated aspect of military history!

January 20, 2020

The reasons HMS Queen Elizabeth has two islands – Russia copied the twin island design

Military TV

Published 5 Jan 2020Many have wondered why HMS Queen Elizabeth has two “islands”. Here we consider why she is the first aircraft carrier in the world to adopt this unique arrangement and the benefits it brings.

REDUNDANCY AND SEPARATION CAN BE GOOD

In a moment of inspiration back in 2001, an Royal Navy officer serving with the Thales CVF design team developing initial concepts for what became the Queen Elizabeth class, hit upon the idea of separate islands. There are several advantages to this design but the most compelling reason for the twin islands is to space out the funnels, allowing greater separation between the engines below. Queen Elizabeth class has duplicated main and secondary machinery in two complexes with independent uptakes and downtakes in each of the two islands. The separation provides a measure of redundancy, it increases the chances one propulsion system will remain operational in the event of action damage to the other. Gas turbine engines (situated in the sponsons directly below each island of the Queen Elizabeth class) by their nature require larger funnels and downtakes than the diesel engines (in the bottom of the ship). The twin island design helps minimise their impact on the internal layout.In a conventional single-island carrier design, either you have to have a very long island (like the Invincible class) which reduces flight deck space or, the exhaust trunkings have to be channelled up into a smaller space. There are limits to the angles this pipework may take which can affect the space available for the hangar. The uptakes can also create vulnerabilities, the third HMS Ark Royal was lost to a single torpedo hit in 1941, partly due to progressive engine room flooding through funnel uptakes.

The twin island design has several other benefits. Wind tunnel testing has proved that the air turbulence over the flight deck caused by the wind and the ship’s movement, is reduced by having two islands instead of one large one. Turbulent air is a hindrance to flight operations and aircraft carrier designers always have to contend with this problem. Twin islands allow greater flight deck area because the combined footprint of the two small islands is less than that of a single larger one. By having two smaller islands it allowed each to be constructed as a single block and then shipped to Rosyth to be lifted onto the hull. The forward island was built in Portsmouth and the aft island built in Glasgow.

This arrangement solves another problem by providing good separation for the main radars. The Type 1046 long range air surveillance radar is mounted forward while the Type 997 Artisan 3D medium range radar is aft. Powerful radars, even operating on different frequencies, can cause mutual interference or blind spots if the aerials are mounted too close together. Apart from a slim communications mast, both the Artisan and 1046 have clear, unobstructed arcs.