Timeline – World History Documentaries

Published 31 Dec 2019Lucy Worsley explores the different houses in which Jane Austen lived and stayed, to discover just how much they shaped Jane’s life and novels.

On a journey that takes her across England, Lucy visits properties that still exist, from grand stately homes to seaside holiday apartments, and brings to life those that have disappeared. The result is a revealing insight into one of the world’s best-loved authors.

Content licensed from Beyond Distribution to Little Dot Studios. Any queries, please contact us at: owned-enquiries@littledotstudios.com

March 31, 2020

Jane Austen: Behind Closed Doors (English Literature Documentary) | Timeline

March 15, 2020

Those damned unintended consequences

Sarah Hoyt on the differences between intention and the real world:

Unintended consequences are the bane of social engineers. They are why the “Scientific” and centralized method of governance never worked and will never work. (Sorry, guys, it just won’t.)

Part of it is because humans are contrary. Part of is because humans are chaotic. And part of it is because like weather systems, societies are so complex it’s almost impossible to figure out what a push in any given place will cause to happen in another place.

This is why price controls are the craziest of idiocies. They don’t work in the way they’re intended, but oh, they work in practically all the ways they’re not. So, take price controls on rent. All they really do is create a market in which housing is scarce, landlords don’t maintain their property AND the only people who can afford to live in cities that have rent control are the very wealthy.

BUT Sarah, you say, aren’t rent controls supposed to make them affordable. Yeah. All that and the good intentions will allow you to go skating in hell on the fourth of July weekend.

Let’s be real, okay? I saw rent control up close and personal in Portugal. Rents were controlled and landlords were penalized for “not keeping the property up”.

In Portugal at the time, and here too, most of the time from what I’ve seen, the administration of property might be some management company, but that’s not who OWNS the damn thing. The owners are usually people who bought the property so it would support them in old age/lean times.

To begin with, you’re removing these people’s ability to make money off their legitimately owned property. And no, they’re not the plutocrats bernie bros imagine. These are often people just making it by.

Second, people are going to get the money some other way, because the alternative is dying. And people don’t want to die or be destitute. So they’re going to find the money. I have no idea what it is in NYC, etc, but in Portugal? it was “key buying.” Sure, you can rent the house for the controlled price, but you have to make a huge payment upfront to “buy the key.” From what I remember this was on the order of a small house down payment. And if you couldn’t do that, you were stuck getting married and living with your parents. And if you say “greedy landlords” — well, see the other thing you could do was leave the lease in your will. So the landlord didn’t know if they’d ever get control of their property back, and they needed to live off this for x years (estimated length of life.) So, that was an unintended consequence. The kind that keeps surfacing in rent-controlled cities in the US.

The same applies to attempts to “help” the homeless. Part of this, as part of all attempts to “fix” poverty is that the people doing it, usually the result of generations of middle class parents and strives assume the homeless and the poor are people like them.

To an extent, they’re correct. The homeless and the poor are PEOPLE. But culture makes a difference, and culture is often based on class and place of upbringing. And the majority of humanity, judging by the world, might be made to strive but are not natural strivers. Without incentive, most of humanity sits back, relaxes and takes what it’s given.

October 2, 2019

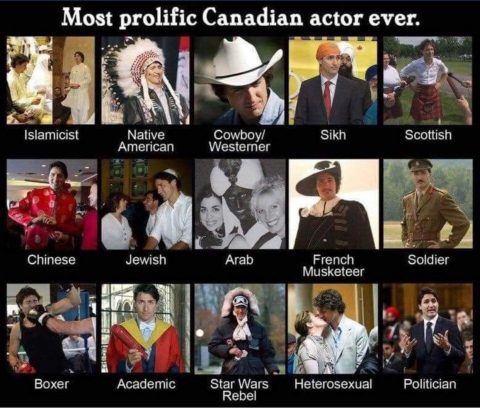

In a crowded field, Election 2019 may be the worst we’ve seen so far

Chris Selley makes the case that this year’s federal election is the worst of all:

It has been widely suggested that this might be Canada’s Worst Election. Certainly it is dreary as all get-out. We began with interminable back-and-forth about abortion, which all party leaders pledge to do absolutely nothing about. If one or more of them are lying, it seems very unlikely they would admit to it at a press conference. The next mania was over Justin Trudeau’s blackface revues, which were radioactively damaging to whatever was left of his Most Enlightened Gentleman brand, but which mostly served as an opportunity for exhibitionist partisan insanity and cringeworthy journalism.

[…]

By rights the Conservatives should be mopping the floor. But they can hardly attack Trudeau’s social-engineer budgeting when they’re relaunching their flotilla of boutique tax credits for kids’ sports and arts programs and public transit. Why not just make their tax cut even bigger and let people spend their money how they please?

Similarly, the Conservatives would be on much firmer ground criticizing Trudeau’s housing-market interventions if they weren’t promising to review the mortgage stress test and bring back 30-year mortgages — something Stephen Harper’s government eliminated in 2012. Having decided carbon pricing was evil almost entirely because Justin Trudeau supports it, the Tories still struggle to defend any effective or efficient policy against climate change.

Any hope that Maxime Bernier might hold Scheer’s feet to the fire on free minds and free markets went up in flames ages ago as his People’s Party attracted far more authoritarian/nativist refugees from the Conservative Party of Canada than libertarian ones. Jagmeet Singh is bargaining hard to sell the NDP’s credibility down the river to appease all-but-totally uninterested Quebec nationalists — shamefully promising not to intervene against Bill 21, as if he would ever get the chance. Elizabeth May and her Green Party constantly remind us that they’re really quite odd: May insisting Longueuil candidate Pierre Nantel isn’t a separatist while Nantel shouts “I’m a separatist!” through a bullhorn is the weirdest thing she has done since the last weird thing.

The debates have worked out as badly as conceivably possible: The Leaders’ Debate Commission, created by the Liberals to solve a problem that didn’t exist — aieeee! Too many debates! — has reinvented the wheel, crushing both Maclean’s debate (which Trudeau declined to attend) and the Munk debate on foreign affairs (which has been cancelled due to Trudeau’s lack of interest) beneath it.

June 18, 2019

QotD: The birth of Jesus and the open concept house

Jesus was not born in a stable. That’s not to say the birth wasn’t attended by farm animals — the Gospel of Luke tells us twice the baby’s first bed was a feeding trough — but rather that the animals lived in the house.

Peasant homes in first century Bethlehem were designed with what we would today call an “open concept.” They typically had one large room with the nicer living space in an open loft or on the roof, while the main floor area was where the family’s animals would be brought for safekeeping at night. The guestroom that was unavailable to Jesus, Mary, and Joseph was that loft or roof space, and the big room where they stayed instead served as the kitchen, living room, dining room, and farmyard all at once. The defining feature of Jesus’ birthplace was not isolation, as we often tend to think, but an utter lack of privacy: Mary delivered in a crowded farmhouse with few, if any, interior walls.

And that was perfectly normal, if not exactly desirable, for our modern fixation on the open floor plan is a historical anomaly. It flies in the face of literally millennia of consensus that more rooms is better, and it is a dreadful mistake. The last 70 years of open concept construction and remodeling has left us with dysfunctional houses, homes that are less conducive to hospitality, less energy efficient, and more given to mess.

Bonnie Kristian, “Open concept homes are for peasants”, The Week, 2019-05-12.

March 21, 2019

“It’s back to normal, basically. The emperor is naked. Votes are for sale. Caveat emptor“

Chris Selley somehow seems, I dunno, a bit … cynical about Prime Minister Trudeau and Finance Minister Morneau’s 2019 federal (election) budget:

Ahoy there, relatively young and middle-class Canadian! Did you vote Liberal in 2015? And are you, shall we say, somewhat less enthused about that prospect four years later, for various reasons we needn’t go into here?

Now, what if Justin Trudeau were to offer you a down payment on a shiny new condominium?

Well, that’s just the kind of guy he is. Starting this year, so long as your household income is below $120,000, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation will pitch in 5 per cent of the price of your first home — 10 per cent if it’s a new home, the construction of which the government hopes to incentivize.

That’s Item One in the 460-page federal budget tabled Tuesday in Ottawa.

On a new $400,000 condo, you could put down your own $20,000; CMHC would chip in another $40,000; and your monthly mortgage payment, on a 25-year term at 3.25 per cent, would drop by a not inconsiderable 12 per cent. You would reimburse CMHC, interest-free, if and when you sell. Cost to the taxpayer: $121 million over six years.

If you’re worried giving home-seekers free money might just push the price of a $400,000 condominium nearer to $440,000, Finance Minister Bill Morneau would first of all like you to stop. (“You’re wrong,” he admonished a reporter who dared suggest it during a press conference in the budget lockup Tuesday.) But if all else fails and you’re forced to rent, the feds also found $10 billion extra over nine years to throw at the Rental Construction Financing Initiative, a CMHC program that offers low-interest loans to qualified builders. The goal is 42,500 new rental units in a decade.

Can’t even think of home ownership until you pay off your student loans? Again, the government is here to help: From now on you’ll pay the Bank of Canada’s prime interest rate, instead of prime plus 2.5 points. And for the first six months after you graduate, you’ll pay nothing. The budget document introduces us to Angela, a recent psychology grad carrying $13,500 in student debt who landed a job at “a medium-sized consumer goods company.” (It doesn’t matter where she works. The writers just wanted to add some colour.) Angela will save something like $2,000 in interest over 10 years.

There’s also the new Canada Training Benefit, which the government intends to help Canadians with “the evolving nature of work.” (Maybe your parents were right, Angela. Maybe that psych degree wasn’t the best idea, Angela.) Starting in 2020, the feds will chip in $250 a year, and you can use the accumulated credit to pay up to half the cost of courses or training. And you can draw on up to four weeks of EI to complete it.

February 4, 2019

QotD: Brasilia and reconciling with Jane Jacobs

Brasilia is interesting only insofar as it was an entire High Modernist planned city. In most places, the Modernists rarely got their hands on entire cities at once. They did build a number of suburbs, neighborhoods, and apartment buildings. There was, however, a disconnect. Most people did not want to buy a High Modernist house or live in a High Modernist neighborhood. Most governments did want to fund High Modernist houses and neighborhoods, because the academics influencing them said it was the modern scientific rational thing to do. So in the end, one of High Modernists’ main contributions to the United States was the projects – ie government-funded public housing for poor people who didn’t get to choose where to live.

I never really “got” Jane Jacobs. I originally interpreted her as arguing that it was great for cities to be noisy and busy and full of crowds, and that we should build neighborhoods that are confusing and hard to get through to force people to interact with each other and prevent them from being able to have privacy, and no one should be allowed to live anywhere quiet or nice. As somebody who (thanks to the public school system, etc) has had my share of being forced to interact with people, and of being placed in situations where it is deliberately difficult to have any privacy or time to myself, I figured Jane Jacobs was just a jerk.

But Scott has kind of made me come around. He rehabilitates her as someone who was responding to the very real excesses of High Modernism. She was the first person who really said “Hey, maybe people like being in cute little neighborhoods”. Her complaint wasn’t really against privacy or order per se as it was against extreme High Modernist perversions of those concepts that people empirically hated. And her background makes this all too understandable – she started out as a journalist covering poor African-Americans who lived in the projects and had some of the same complaints as Brazilians.

Her critique of Le Corbusierism was mostly what you would expect, but Scott extracts some points useful for their contrast with the Modernist points earlier:

First, existing structures are evolved organisms built by people trying to satisfy their social goals. They contain far more wisdom about people’s needs and desires than anybody could formally enumerate. Any attempt at urban planning should try to build on this encoded knowledge, not detract from it.

Second, man does not live by bread alone. People don’t want the right amount of Standardized Food Product, they want social interaction, culture, art, coziness, and a host of other things nobody will ever be able to calculate. Existing structures have already been optimized for these things, and unlesss you’re really sure you understand all of them, you should be reluctant to disturb them.

Third, solutions are local. Americans want different things than Africans or Indians. One proof of this is that New York looks different from Lagos and from Delhi. Even if you are the world’s best American city planner, you should be very concerned that you have no idea what people in Africa need, and you should be very reluctant to design an African city without extensive consultation of people who understand the local environment.

Fourth, even a very smart and well-intentioned person who is on board with points 1-3 will never be able to produce a set of rules. Most of people’s knowledge is implicit, and most rule codes are quickly replaced by informal systems of things that work which are much more effective (the classic example of this is work-to-rule strikes).

Fifth, although well-educated technocrats may understand principles which give them some advantages in their domain, they are hopeless without the on-the-ground experience of the people they are trying to serve, whose years of living in their environment and dealing with it every day have given them a deep practical knowledge which is difficult to codify.

How did Jacobs herself choose where to live? As per her Wikipedia page:

[Jacobs] took an immediate liking to Manhattan’s Greenwich Village, which did not conform to the city’s grid structure.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Seeing Like a State”, Slate Star Codex, 2017-03-16.

December 10, 2018

Minneapolis abolishes residential zoning to combat racist segregation

I’ve never actually been to Minnesota (despite being a lifetime fan of the Minnesota Vikings), so I didn’t realize that Minneapolis — and presumably other Minnesota cities historically instituted residential zoning to enforce racial segregation:

Minneapolis will become the first major U.S. city to end single-family home zoning, a policy that has done as much as any to entrench segregation, high housing costs, and sprawl as the American urban paradigm over the past century.

On Friday, the City Council passed Minneapolis 2040, a comprehensive plan to permit three-family homes in the city’s residential neighborhoods, abolish parking minimums for all new construction, and allow high-density buildings along transit corridors.

“Large swaths of our city are exclusively zoned for single-family homes, so unless you have the ability to build a very large home on a very large lot, you can’t live in the neighborhood,” Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey told me this week. Single-family home zoning was devised as a legal way to keep black Americans and other minorities from moving into certain neighborhoods, and it still functions as an effective barrier today. Abolishing restrictive zoning, the mayor said, was part of a general consensus that the city ought to begin to mend the damage wrought in pursuit of segregation. Human diversity — which nearly everyone in this staunchly liberal city would say is a good thing — only goes as far as the housing stock.

It may be as long as a year before Minneapolis zoning regulations and building codes reflect what’s outlined in the 481-page plan, which was crafted by city planners. Still, its passage makes the 422,000-person city, part of the Twin Cities region, one of the rare U.S. metropolises to publicly confront the racist roots of single-family zoning—and try to address the issue.

“A lot of research has been done on the history that’s led us to this point,” said Cam Gordon, a city councilman who represents the Second Ward, which includes the University of Minnesota’s flagship campus. “That history helped people realize that the way the city is set up right now is based on this government-endorsed and sanctioned racist system.” Easing the plan’s path to approval, he said, was the fact that modest single-family homes in appreciating neighborhoods were already making way for McMansions. Why not allow someone to build three units in the same-size building? (Requirements on height, yard space, and permeable surface remain unchanged in those areas.)

November 19, 2018

“You call someplace paradise/kiss it goodbye”

The Eagles song “The Last Resort” references a generic paradise, not the California town of that name, yet it fits disturbingly well, as Gerard Vanderleun describes:

Paradise is not a town on some flat land out on the prairies or deep in the desert. Paradise is a series of cleared areas and roads superimposed on an extremely rugged terrain composed of deep, narrow ravines and high and densely wood ridges. The Skyway is fed by hundreds of paved and unpaved roads that twist and turn and rise and dip and then, at their OFFICIAL ends, run deeper still and far off the grid. If you live in Paradise you know there are hundreds of people living back up in those ravines and ridges that would be hard to find before the fire. In those places, the poor are lodged tighter than ticks.

I’ve seen, before the fire this time, people in the outback of Paradise so abidingly poor they were living in trailers from the 70s resting on cinder blocks and at most only two winters away from a pile of rust. These people would have had no warning of a fire, no warning at all. Instead of “sheltering in place” they would have been “incinerated in place.”

In the ravines and forests of Paradise, cell reception was so spotty that AT&T gave me my own personal internet driven cell-phone tower. If those off the grid in Paradise actually owned cell phones they would have been lucky to get an alert. But most of those did not own cell phones, and landlines didn’t run that deep in the woods. When the fire closed over them they would have had no warning. No warning until the trailer melted around them. And then there was, out behind but still close to their trailer, their large propane tank.

November 17, 2018

Modern houses are not flexible

Kate Wagner, of McMansion Hell fame, discusses the pressures that have combined to create the modern western house and why they are not as flexible in use as we really need:

Houses are a particular paradox. We expect them to serve as long-term, if not permanent, shelter — the word “mortgage” even has the prefix mort, death, implying that the house will live longer than we will — but we also expect them to shift in response to our needs and desires. As Christopher Alexander writes in his treatise The Timeless Way of Building, “You want to be able to mess around with it and progressively change it to bring it into an adapted state with yourself, your family, the climate … to reflect the variety of human situations.”

That is exactly what we want — and we’ve gone about it in exactly the wrong way. We’ve ended up with overstuffed houses that attempt to anticipate every direction our lives could go, when what we need are flexible houses that can adapt to the lives we’re actually living.

But flexibility rarely comes up, as [Stewart] Brand points out in his book [How Buildings Learn], in the fevered brouhaha of building and architectural consumption. And if we’re going to rethink how flexible our houses are, we need to do so at the level of our structures and the way they are built.

[…]

Of course, the premier example of a house designed for stuff is the McMansion, which, as I have argued at length elsewhere, is designed from the inside out. The reason it looks the way it does is because of the increasingly long laundry list of amenities (movie theaters, game rooms) needed to accumulate the highest selling value and an over-preparedness for the maximum possible accumulation of both people (grand parties) and stuff (grand pianos). This comes at the expense of structure, skin, and services. The structure becomes wildly convoluted, having to accommodate both ceilings of towering heights and others half that size, often within the same volume. Because of this, the rooflines are particularly complex, featuring several different pitches and shapes, and the walls are peppered with large great-room windows (a selling feature!), and other windows on any given elevation consist of many different sizes and shapes.

The skin — which often features many different types of cladding — and the roof are, due to their complexity, more prone to vulnerabilities, such as leaks. Because of the equally complex internal space plan, often following the trend of more and more open floorplans and large internal volumes, services like heating and cooling have to combat irregular volumes and energy leakage through features like massive picture windows. Rooms are programmed for specific activities: craft rooms, man caves, movie theaters. This is a kind of architectural stockpiling, devoting space to hobbies that could easily be performed in other parts of the house, out of a strange fear of not having enough space.

November 6, 2018

An alternative explanation for the population explosion of the “land whales”

Tim Worstall suggests that the real reason for our collective expanding waistlines isn’t evil capitalist exploiters pushing us to eat unhealthy fast food:

We don’t, for example, eat more than our forefathers did. Sure, we can all play games with how much people lie on those self-reported surveys about calorie intake. True, to make sense of it being lies we’d have to assume that people lie more now than they used to. So, instead, let’s look at official guidance. In WW1 the aim was, for the Army, to stuff some 4,300 calories a day into each frontline soldier out there in the trenches. Something they largely achieved too. In WWII rationing peeps started to worry that diets of less than 2,900 calories a day would lead to weight loss. Today official guidance is that 2,500 a day for men, 2,000 for women. Well, that’s the last one I recall at least.

I suspect that people actually do lie more on self-reporting surveys of that kind than they once did, if only because we’ve had several decades of prissy lecturing about what we should consume … the temptation to shade the answers in the “right” direction I’m sure plays some part, but not enough to explain the obesity crisis. If you doubt that this happens, remember that a significant number of people vote for the party they expect to win rather than the party that best represents their interests or desires. Sucking up to teacher is a very common psychological trait.

However, back to the swelling obesity numbers:

Actually, 40 years ago is about when central heating became a commonplace in Britain. Anyone of my maturity in years – which includes G. Monbiot – and even those from thoroughly upper middle class backgrounds – both me and G. Monbiot – will recall ice on the inside of bedroom windows in winter. Houses simply were not fully heated throughout. Actually, pretty much the entire country was in what we’d now call fuel poverty. That fuel poverty that we have standards for these days, you should be able to heat the entire house to such and such a temperature on less than 10% of income. A standard which just about no one pre-1950 reached, few pre-1970 did.

America had that heating rather earlier than we did. Americans also became land whales that little bit earlier than we did. Anecdata I know but a move to the US in 1981 was marked with an observation of how warm Americans kept their houses in winter.

We do actually spend quite a lot on all this public health stuff these days. It might be worth someone doing a little study of correlations. Different nations became lardbuckets at different times. Different nations adopted central heating as a commonplace at different times. Why don’t we go see what the correlation between those two is?

After all, the idea that mammals use some significant portion of their energy intake for body temperature regulation isn’t exactly fringe science, is it?

October 16, 2018

Fast food outlets cluster in poorer areas – because they’re low-margin businesses

Tim Worstall debunks the “fast food restaurants are preying on the poor” myth:

Contrary to the musings of Rod Liddle in the Sunday Times there is a cause and effect going on over the placings of fast food restaurants or outlets in British towns. The provision of burnt chicken and maybemeatburgers to the hoi polloi is a hugely competitive business. This means that it is also low margin. So, where do you put the places that are in a low margin line of business?

[…] this is about clustering of those nosh joints. Why are they in the poor areas? Well, for the same reason the poor are in the poor areas. They’re cheap. This being rather the defining point about poor people, they look for cheap places to live. The two are therefore synonymous, poor and cheap. And what is it we’ve just said about nosh? That it’s a low margin business. Therefore purveyors of the deep fried and battered saveloy – that joy of the ages – are going to be clustered in the poor part of town where they can afford the rents.

And that’s our cause and effect. Some poor people are poor because they’re, or have been, ill. They’re in the cheap part of town because they’re poor. Fried gut shops are in poor areas because they don’t make much money therefore they’re in the poor part of town. Absolutely any analysis of the phenomenon which doesn’t account for this is wrong. And no analysis done by anyone does take account of it – therefore all current analyses of the point are indeed wrong.

There are also other factors to consider, including the fact that poor people are less likely to have the ability or facilities to prepare their own meals (or the habit of cooking for themselves), so the easy availability of high-calorie fast food or snacks is rather important to them. When you’re hungry and don’t have a fridge or freezer full of food at home, a burger or fried chicken has a much stronger appeal than it does to more wealthy folks with well-stocked pantries. If you’ve been raised on high-fat/high-salt foods, the “healthier” alternatives may not appeal, as they also are less flavourful than their fast food options.

October 2, 2018

Costs of Inflation: Financial Intermediation Failure

Marginal Revolution University

Published on 7 Feb 2017In the previous video, we learned that inflation can add noise to price signals resulting in some costly mistakes from price confusion and money illusion. Now, we’ll look at how it can interfere with long-term contracting with financial intermediaries.

Let’s say you want to take out a big loan, such as a mortgage on a house. The financial intermediary (in this case, a commercial bank) is going to charge you an interest rate as their profit for loaning you the money. In this situation, inflation has the potential to work against you or it can work against the bank.

If the bank charges you a nominal interest rate (i.e., the interest rate on paper before taking inflation into account) of 5% and inflation climbs unexpectedly to 10% for the year, the real interest rate (nominal minus inflation) falls to -5%. The bank actually loses money. However, if inflation has been higher and banks are charging 15% for mortgages and inflation rates fall unexpectedly to 3%, you’re stuck paying a real interest rate of 12%!

The above scenarios are similar to what actually happened in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. Inflation was low in the 60s. But then in 70s, inflation rates climbed up unexpectedly. People that purchased a home in the 60s lucked out with low interest rates on their mortgages coupled with higher inflation, and many were able to pay off the loans more quickly than expected. But anyone that purchased a higher interest rate mortgage in the 70s only saw inflation fall back down. It was good for the banks and a costly choice for the homeowners. They were saddled with a high-interest mortgage while lower inflation meant a lower increase in wages.

It’s not that the people buying homes in the 1960s were smarter than those in the 70s. As we’ve noted in previous videos, inflation can be very difficult to predict. When banks expect that inflation might be 10% in the coming years, they will generally adjust their nominal interest rates in order to achieve the desired real interest rate. This relationship between real and nominal interest rates and inflation is known as the Fisher effect, after economist Irving Fisher.

We can see the Fisher effect in the data for nominal interest rates on U.S. mortgages from the 1960s through today. As inflation rates rise, nominal interest rates try to keep up. And as the inflation rates fall, nominal interest rates trail behind.

Now, if inflation rates are both high and volatile, lending and borrowing gets scary for both sides. Long-term contracts like mortgages become more costly for everyone with much higher risk, so it happens less. This is damaging for an economy. Coordinating saving and investment is an important function of the market. If high and volatile inflation is making that inefficient and less common, total wealth declines.

Up next, we’ll explore why governments create inflation in the first place.

September 7, 2018

QotD: Government distortion of the housing market

Behind the veneer of free-market governance is a deep expanse of government involvement in massive areas of the economy, such as the housing market and health care. People don’t make decisions on housing and health-care concerns every day, but when they do, they would benefit from the information that markets provide about whether they can afford a large house or whether a particular drug is worth the price. Government distortion of these key markets has scrambled these signals.

An annual congressional report, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures,” gives insight into how Washington manipulates supply and demand in these sectors. Consider house prices. This year, Washington will pay homeowners $99 billion in forgone taxes to borrow money to purchase or refinance a house or to sell that house and reap the profit. Americans will buy or sell about $600 billion worth of houses this year. Government subsidy, then, represents nearly one-sixth of this market. The federal government also provides a guarantee for most mortgages, thanks to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-supported mortgage companies that benefited for decades from an implicit government guarantee before they got an explicit guarantee during the 2008 financial crisis.

These subsidies have fired the growth of the housing industry. Between 1975 and 1979, the U.S. Treasury paid out $102.6 billion in mortgage-interest breaks in today’s dollars. Between 2015 and 2019, the Treasury will pay out $419.8 billion in such tax favoritism — a more than fourfold rise, nearly ten times the population increase. The hike is particularly extraordinary, considering that in the late 1970s, the annual interest rate on a mortgage was 9 percent, twice what it is today. Taking today’s lower rates into account, Washington has increased the mortgage subsidy more than eightfold.

It’s no surprise that mortgage debt has soared, to $9.5 trillion, from $2.6 trillion in inflation-adjusted dollars in 1981. Back then, mortgage debt constituted 31 percent of our nation’s GDP. Today, it makes up nearly 53 percent. [Dierdre] McCloskey, who thinks that free markets are generally healthy, acknowledges that “there are examples of the price signal not coming through.” The mortgage-interest deduction is “a silly idea,” she says, yet “very hard to change.”

Indeed, government subsidy is a critical factor in whether families can afford to purchase a home, and what kind of home, how large, and in what zip code. The home-mortgage deduction, then, helps determine how people live — yet we barely notice. Few of us consider how the government shapes one of the biggest decisions we’ll ever make, or how the U.S. government’s presence in the housing market maintains the value of our homes.

Nicole Gelinas, “Fake Capitalism: It’s not free markets that have failed us but government distortion of them”, City Journal, 2016-11-06.

August 2, 2018

Manufacturing the Engineered Wood Floor Joists

Bob Vila

Published on 30 Mar 2015Bob visits the Willamette I-Joist Mill in Woodburn, OR, before returning to Yonkers where the crew is assembling the second floor walls with structural insulated panels.

July 31, 2018

A gruesome experiment in determining the actual need for social housing

Tim Worstall discusses an aspect of the terrible Grenfell Tower fire in London that I hadn’t considered:

That the Grenfell Tower fire was a tragedy is obvious. That lessons need to be learned is equally so. At which point, OK, which lessons would we like to learn? One that would be useful is to work out how much of social housing in London – for that’s what the evidence allows us to estimate – is illegally sublet. Or, as we might also put it, how much social housing in London is not actually needed as social housing?

For sublets are, by their nature, at something close to market rents, the difference between those and the social rents being pocketed by those doing the renting out.

No, we don’t know and that might be just because we’ve not been paying the detailed attention required. But it’s also something we tend to think will have been glossed over in investigations into the events. Something that perhaps should not have been glossed over – if indeed it has.

[…] The thought that a place, in the centre of London, where we could house – safely perhaps this time – several hundred people not be used to house several hundred people? We have a housing shortage or not?

However, it’s the insight into that larger question that interests. We know that some amount of social (and or council) housing in London is illegally sublet. The very fact that it is shows that it’s not needed. Those who are paying the landlord a reduced rent clearly don’t need the property as they’re not living in it. Those paying the near market rents don’t need social housing as they’re paying near market rents. Thus subletting shows that the entire structure of – at least in that instance – the social rent isn’t necessary.

So, how prevalent is it? We know that some of it occurred at Grenfell. We’ve all admitted it, clearly, for we’ve not insisted that only those on the tenants’ listing are those who should be granted aid for having had their home burned down. So, we know there’s some. So, how much?

It’s unlikely that we’ve as much information on this concerning any other building in the country. Thus this is an excellent place to actually conduct such research.