Herbert Hoover spent his entire presidency miserable.

First, he has no doubt that the economy is going to crash. It’s been too good for too long. He frantically tries to cool down the market, begs moneylenders to stop lending and bankers to stop banking. It doesn’t work, and the Federal Reserve is less concerned than he is. So he sits back and waits glumly for the other shoe to drop.

Second, he hates politics. Somehow he had thought that if he was the President, he would be above politics and everyone would have to listen to him. The exact opposite proves true. His special session of Congress comes up with the worst, most politically venal tariff bill imaginable. Each representative declares there should be low tariffs on everything except the products produced in his own district, then compromises by agreeing to high tariffs on everything with good lobbyists. The Senate declares that the House of Representatives is corrupt nincompoops and sends the bill back in disgust. Hoover has no idea how to solve this problem except to ask the House to do some kind of rational economically-correct calculation about optimal tariffs, which the House finds hilarious. “Opposed to the House bill and divided against itself, the Senate ran out the remaining seven weeks [of the special session] in a debauch of taunts, accusations, recriminations, and procedural argument.” The public blames Hoover, pretty fairly – a more experienced president would have known how to shepherd his party to a palatable compromise.

Also, there are crime waves, prison riots, bootlegging, and a heat wave during which Washington DC is basically uninhabitable. Also, at one point the White House is literally on fire.

… and then the market finally crashes. Hoover is among the first to call it a Depression instead of a Panic – he thinks the new term might make people panic less. But in fact, people aren’t panicking. They assume Hoover has everything in hand.

At first he does. He gathers the heads of Ford, Du Pont, Standard Oil, General Electric, General Motors, and Sears Roebuck and pressures them to say publicly they won’t fire people. He gathers the AFL and all the union heads and pressures them to say publicly they won’t strike. He enacts sweeping tax cuts, and the Fed enacts sweeping rate cuts. Everyone is bedazzled […] Six months later, employment is back to its usual levels, the stock market is approaching its 1929 level, and Democrats are fuming because they expect Hoover’s popularity to make him unbeatable in the midterms. I got confused at this point in the book – did I accidentally get a biography from an alternate timeline with a shorter, milder Great Depression? No – this would be the pattern throughout the administration. Hoover would take some brilliant and decisive action. Economists would praise him. The economy would start to look better. Everyone would declare the problem solved – especially Hoover, sensitive both to his own reputation and to the importance of keeping economic optimism high. Then the recovery would stall, or reverse, or something else would go wrong.

People are still debating what made the Great Depression so long and hard. Whyte’s theory, insofar as he has one at all, is “one thing after another”. Every time the economy started to go up (thanks to Hoover), there was another shock. Most of them involved Europe – Germany threatening to default on its debts, Britain going off the gold standard. A few involved the US – the Federal Reserve made some really bad calls. The one thing Whyte is really sure about is that his idol Herbert Hoover was totally blameless.

He argues that Hoover’s bank relief plan could have stopped the Depression in its tracks – but that Congressional Democrats intent on sabotaging Hoover forced the plan to publicize the names of the banks applying. The Democrats hoped to catch Hoover propping up his plutocrat friends – but the change actually had the effect of making banks scared to apply for funding and panicking the customers of banks that were known to have applied. He argues that the “Hoover Holiday” – a plan to grant debt relief to Germany, taking some pressure off the clusterf**k that was Europe – was a masterstroke, but that France sabotaged it in the interests of bleeding a few more pennies from its arch-rival. International trade might have sparked a recovery – except that Congress finally passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, the end result of the corruption-plagued tariff negotiations, just in time to choke it off.

Whyte saves his barbs for the real villain: FDR. If the book is to be believed, Hoover actually had things pretty much under control by 1932. Employment was rising, the stock market was heading back up. FDR and his fellow Democrats worked to tear everything back down so he could win the election and take complete credit for the recovery. The wrecking campaign entered high gear after FDR won in 1932; he was terrified that the economy might get better before he took office, and used his President-Elect status to hint that he was going to do all sorts of awful things. The economy got skittish again and obediently declined, allowing him to get inaugurated at the precise lowest point and gain the credit for recovery he so ardently desired.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

March 23, 2025

QotD: Herbert Hoover as president

March 11, 2025

QotD: Herbert Hoover wins the presidency

Finally, it is 1928. Hoover feels like he has accomplished his goal of becoming the sort of knowledgeable political insider who can run for President successfully. Calvin Coolidge decides not to run for a second term (in typical Coolidge style, he hands a piece of paper to a reporter saying “I do not choose to run for President in 1928” and then disappears and refuses to answer further questions). The Democrats nominate Al Smith, an Irish-Italian Catholic with a funny accent; it’s too early for the country to really be ready for this. Historians still debate whether Hoover and/or his campaign deserves blame for being racist or credit for being surprisingly non-racist-under-the-circumstances.

The main issue is Prohibition. Smith, true to his roots, is against. Hoover, true to his own roots (his mother was a temperance activist) is in favor. The country is starting to realize Prohibition isn’t going too well, but they’re not ready to abandon it entirely, and Hoover promises to close loopholes and fix it up. Advantage: Hoover.

The second issue is tariffs. Everyone wants some. Hoover promises that if he wins, he will call a special session of Congress to debate the tariff question. Advantage: Hoover.

The last issue is personality. Republican strategists decide the best way for their candidate to handle his respective strengths and weaknesses is not to campaign at all, or be anywhere near the public, or expose himself to the public in any way. Instead, they are “selling a conception. Hoover was the omnicompetent engineer, humanitarian, and public servant, the ‘most useful American citizen now alive’. He was an almost supernatural figure, whose wisdom encompasses all branches, whose judgment was never at fault, who knew the answers to all questions.” Al Smith is supremely charismatic, but “boasted of never having read a book”. Advantage: unclear, but Hoover’s strategy does seem to work pretty well for him. He racks up most of the media endorsements. Only TIME Magazine dissents, saying that “In a society of temperate, industrious, unspectacular beavers, such a beaver-man would make an ideal King-beaver. But humans are different.”

Apparently not that different. Hoover wins 444 votes to 87, one of the greatest electoral landslides in American history.

Anne McCormick of the New York Times describes the inauguration:

We were in a mood for magic … and the whole country was a vast, expectant gallery, its eyes focused on Washington. We had summoned a great engineer to solve our problems for us; now we sat back comfortable and confidently to watch our problems being solved. The modern technical mind was for the first time at the head of a government. Relieved and gratified, we turned over to that mind all of the complications and difficulties no other had been able to settle. Almost with the air of giving genius its chance, we waited for the performance to begin.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

December 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover in the Harding and Coolidge years

[Herbert] Hoover wants to be president. It fits his self-image as a benevolent engineer-king destined to save the populace from the vagaries of politics. The people want Hoover to be president; he’s a super-double-war-hero during a time when most other leaders have embarrassed themselves. Even politicians are up for Hoover being president; Woodrow Wilson has just died, leaving both Democrats and Republicans leaderless. The situation seems perfect.

Hoover bungles it. He plays hard-to-get by pretending he doesn’t want the Presidency, but potential supporters interpret this as him just literally not wanting the Presidency. He refuses to identify as either a Democrat or Republican, intending to make a gesture of above-the-fray non-partisanship, but this prevents either party from rallying around him. Also, he might be the worst public speaker in the history of politics.

Warren D. Harding, a nondescript Senator from Ohio, wins the Republican nomination and the Presidency. Hoover follows his usual strategy of playing hard-to-get by proclaiming he doesn’t want any Cabinet positions. This time it works, but not well: Harding offers him Secretary of Commerce, widely considered a powerless “dud” position. Hoover accepts.

Harding is famous for promising “return to normalcy”, in particular a winding down of the massive expansion of government that marked WWI and the Wilson Administration. Hoover had a better idea – use the newly-muscular government to centralize and rationalize American In his first few years in Commerce – hitherto a meaningless portfolio for people who wanted to say vaguely pro-prosperity things and then go off and play golf – Hoover instituted/invented housing standards, traffic safety standards, industrial standards, zoning standards, standardized electrical sockets, standardized screws, standardized bricks, standardized boards, and standardized hundreds of other things. He founded the FAA to standardize air traffic, and the FCC to standardize communications. In order to learn how his standards were affecting the economy, he founded the NBER to standardize government statistics.

But that isn’t enough! He mediates a conflict between states over water rights to the Colorado River, even though that would normally be a Department of the Interior job. He solves railroad strikes, over the protests of the Department of Labor. “Much to the annoyance of the State Department, Hoover fielded his own foreign service.” He proposes to transfer 16 agencies from other Cabinet departments to the Department of Commerce, and when other Secretaries shot him down, he does all their jobs anyway. The press dub him “Secretary of Commerce and Undersecretary Of Everything Else”.

Hoover’s greatest political test comes when the market crashes in the Panic of 1921. The federal government has previously ignored these financial panics. Pre-Wilson, it was small and limited to its constitutional duties – plus nobody knows how to solve a financial panic anyway. Hoover jumps into action, calling a conference of top economists and moving forward large spending projects. More important, he is one of the first government officials to realize that financial panics have a psychological aspect, so he immediately puts out lots of press releases saying that economists agree everything is fine and the panic is definitely over. He takes the opportunity to write letters saying that Herbert Hoover has solved the financial panic and is a great guy, then sign President Harding’s name to them. Whether or not Hoover deserves credit, the panic is short and mild, and his reputation grows.

While everyone else obsesses over his recession-busting, Hoover’s own pet project is saving the Soviet Union. Several years of civil war, communism, and crop failure have produced mass famine. Most of the world refuses to help, angry that the USSR is refusing to pay Czarist Russia’s debts and also pretty peeved over the whole Communism thing. Hoover finds $20 million to spend on food aid for Russia, over everyone else’s objection […]

So passed the early 1920s. Warren Harding died of a stroke, and was succeeded by Vice-President “Silent Cal” Coolidge, a man famous for having no opinions and never talking. Coolidge won re-election easily in 1924. Hoover continued shepherding the economy (average incomes will rise 30% over his eight years in Commerce), but also works on promoting Hooverism, his political philosophy. It has grown from just “benevolent engineers oversee everything” to something kind of like a precursor modern neoliberalism:

Hoover’s plan amounted to a complete refit of America’s single gigantic plant, and a radical shift in Washington’s economic priorities. Newsmen were fascinated by is talk of a “third alternative” between “the unrestrained capitalism of Adam Smith” and the new strain of socialism rooting in Europe. Laissez-faire was finished, Hoover declared, pointing to antitrust laws and the growth of public utilities as evidence. Socialism, on the other hand, was a dead end, providing no stimulus to individual initiative, the engine of progress. The new Commerce Department was seeking what one reporter summarized as a balance between fairly intelligent business and intelligently fair government. If that were achieved, said Hoover, “we should have given a priceless gift to the twentieth century.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

June 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover as Woodrow Wilson’s “Food Dictator”

In 1917, America enters World War I. Hoover […] returns to the US a war hero. The New York Times proclaims Hoover’s CRB work “the greatest American achievement of the last two years”. There is talk that he should run for President. Instead, he goes to Washington and tells President Woodrow Wilson he is at his service.

Wilson is working on the greatest mobilization in American history. He realizes one of the US’ most important roles will be breadbasket for the Allied Powers, and names Hoover “food commissioner”, in charge of ensuring that there is enough food to support the troops, the home front, and the other Allies. His powers are absurdly vast – he can do anything at all related to the nation’s food supply, from fixing prices to confiscating shipments from telling families what to eat. The press affectionately dubs him “Food Dictator” (I assume today they would use “Food Czar”, but this is 1917 and it is Too Soon).

Hoover displays the same manic energy he showed in Belgium. His public relations blitz telling families to save food is so successful that the word “Hooverize” enters the language, meaning to ration or consume efficiently. But it turns out none of this is necessary. Hoover improves food production and distribution efficiency so much that no rationing is needed, America has lots of food to export to Europe, and his rationing agency makes an eight-digit profit selling all the extra food it has.

By 1918, Europe is in ruins. The warring powers have declared an Armistice, but their people are starving, and winter is coming on fast. Also, Herbert Hoover has so much food that he has to swim through amber waves of grain to get to work every morning. Mountains of uneaten pork bellies are starting to blot out the sky. Maybe one of these problems can solve the other? President Wilson dispatches Hoover to Europe as “special representative for relief and economic rehabilitation”. Hoover rises to the challenge:

Hoover accepted the assignment with the usual claim that he had no interest in the job, simultaneously seeking for himself the broadest possible mandate and absolute control. The broad mandate, he said, was essential, because he could not hope to deliver food without refurnishing Europe’s broken finance, trade, communications, and transportation systems …

Hoover had a hundred ships filled with food bound for neutral and newly liberated parts of the Continent before the peace conferences were even underway. He formalized his power in January 1919 by drafting for Wilson a post facto executive order authorizing the creation of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with Hoover as its executive director, authorized to feed Europe by practically any means he deemed necessary. He addressed the order to himself and passed it to the president for his signature …

The actual delivery of relief was ingeniously improvised. Only Hoover, with his keen grasp of the mechanics of civilization, could have made the logistics of rehabilitating a war-ravaged continent look easy. He arranged to extend the tours of thousands of US Army officers already on the scene and deployed them as ARA agents in 32 different countries. Finding Europe’s telegraph and telephone services a shambles, he used US Navy vessels and Army Signal Corps employees to devise the best-functioning and most secure wireless system on the continent. Needing transportation, Hoover took charge of ports and canals and rebuilt railroads in Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA was for a time the only agency that could reliably arrange shipping between nations …

The New York Times said it was only apparent in retrospect how much power Hoover wielded during the peace talks. “He has been the nearest approach Europe has had to a dictator since Napoleon.”

Once again, Hoover faces not only the inherent challenge of feeding millions, but opposition from the national governments he is trying to serve. Britain and France plan to let Germany starve, hoping this will decrease its bargaining power at Versailles. They ban Hoover from transporting any food to the defeated Central Powers. Hoover, “in a series of transactions so byzantine it was impossible for outsiders to see exactly what he was up to”, causes some kind of absurd logistics chain that results in 42% of the food getting to Germany in untraceable ways.

He is less able to stop the European powers’ controlled implosion at Versailles. He believes 100% in Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a fair peace treaty with no reparations for Germany and a League Of Nations powerful enough to prevent any future wars. But Wilson and Hoover famously fail. Hoover predicts a second World War in five years (later he lowers his estimate to “thirty days”), but takes comfort in what he has been able to accomplish thus far.

He returns to the US as some sort of super-double-war-hero. He is credited with saving tens of millions of lives, keeping Europe from fraying apart, and preventing the spread of Communism. He is not just a saint but a magician, accomplishing feats of logistics that everyone believed impossible. John Maynard Keynes:

Never was a nobler work of disinterested goodwill carried through with more tenacy and sincerity and skill, and with less thanks either asked or given. The ungrateful Governments of Europe owe much more to the statesmanship and insight of Mr. Hoover and his band of American workers than they have yet appreciated or will ever acknowledge. It was their efforts … often acting in the teeth of European obstruction, which not only saved an immense amount of human suffering, but averted a widespread breakdown of the European system.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

September 2, 2022

The winner in 1932 campaigned against high taxes, big government, and more debt. Then he turned all those up to 11

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Lawrence W. Reed notes that we often get the opposite of what we vote for, and perhaps the best example of that was the 1932 presidential campaign between high-taxing, big-spending, government-expanding Republican Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who ran against all of Hoover’s excesses … until inauguration day, anyway:

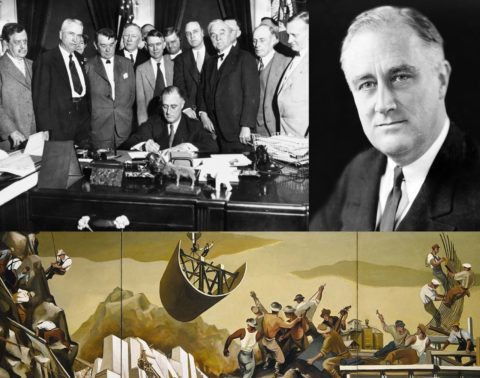

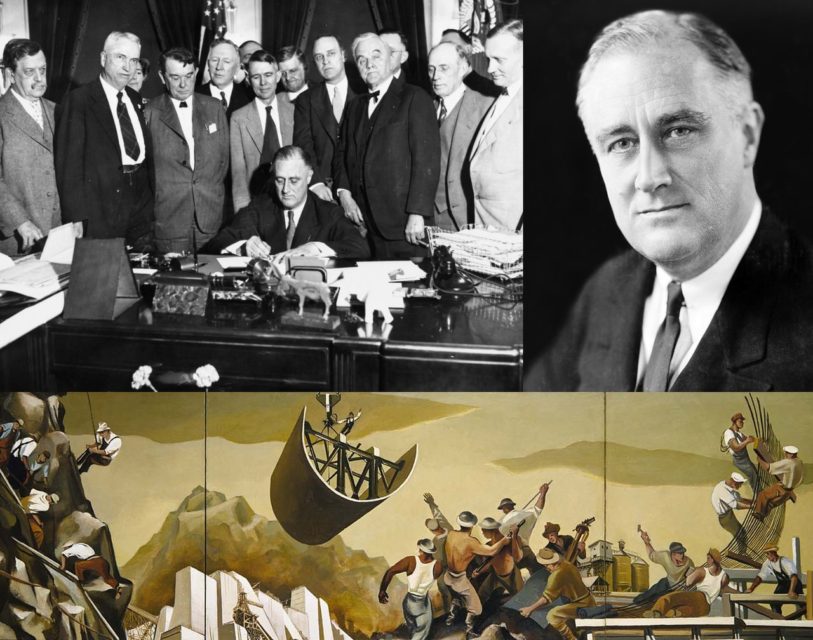

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

If you were a socialist (or a modern “liberal” or “progressive”) in 1932, you faced an embarrassment of riches at the ballot box. You could go for Norman Thomas. Or perhaps Verne Reynolds of the Socialist Labor Party. Or William Foster of the Communist Party. Maybe Jacob Coxey of the Farmer-Labor Party or even William Upshaw of the Prohibition Party. You could have voted for Hoover who, after all, had delivered sky-high tax rates, big deficits, lots of debt, higher spending, and trade-choking tariffs in his four-year term. Roosevelt’s own running mate, John Nance Garner of Texas, declared that Republican Hoover was “taking the country down the path to socialism”.

Journalist H.L. Mencken famously noted that “Every election is a sort of advance auction sale of stolen goods.” If you agreed with Mencken and preferred a non-socialist candidate who promised to get government off your back and out of your pocket in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt was your man — that is, until March 1933 when he assumed office and took a sharp turn in the other direction.

The platform on which Roosevelt ran that year denounced the incumbent administration for its reckless growth of government. The Democrats promised no less than a 25 percent reduction in federal spending if elected.

Roosevelt accused Hoover of governing as though, in FDR’s words, “we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible.” On September 29 in Iowa, the Democrat presidential nominee blasted Hooverism in these terms:

I accuse the present Administration of being the greatest spending Administration in peace times in all our history. It is an Administration that has piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission, and has failed to anticipate the dire needs and the reduced earning power of the people. Bureaus and bureaucrats, commissions and commissioners have been retained at the expense of the taxpayer.

Now, I read in the past few days in the newspapers that the President is at work on a plan to consolidate and simplify the Federal bureaucracy. My friends, four long years ago, in the campaign of 1928, he, as a candidate, proposed to do this same thing. And today, once more a candidate, he is still proposing, and I leave you to draw your own inferences. And on my part, I ask you very simply to assign to me the task of reducing the annual operating expenses of your national government.

Once in the White House, he did no such thing. He doubled federal spending in his first term. New “alphabet agencies” were added to the bureaucracy. Nothing of any consequence in the budget was either cut or made more efficient. He gave us our booze back by ending Prohibition, but then embarked upon a spending spree that any drunk with your wallet would envy. Taxes went up in FDR’s administration, not down as he had promised.

Don’t take my word for it. It’s all a matter of public record even if your teacher or professor never told you any of this. For details, I recommend these books: Burton Folsom’s New Deal or Raw Deal; Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression; my own Great Myths of the Great Depression; and the two I want to tell you about now, John T. Flynn’s As We Go Marching and The Roosevelt Myth.

For every thousand books written, perhaps one may come to enjoy the appellation “classic”. That label is reserved for a volume that through the force of its originality and thoroughness, shifts paradigms and serves as a timeless, indispensable source of insight.

Such a book is The Roosevelt Myth. First published in 1948, Flynn’s definitive analysis of America’s 32nd president is arguably the best and most thoroughly documented chronicle of the person and politics of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Flynn’s 1944 book, As We Go Marching, focuses on the fascist-style economic planning during World War II and is very illuminating as well.

April 12, 2022

Calvin Coolidge: The Silent President

Biographics

Published 27 Sep 2021Simon’s Social Media:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SimonWhistler

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/simonwhistler/This video is #sponsored by Squarespace.

Source/Further reading:

Miller Center, in-depth overview: https://millercenter.org/president/co…

History Today, overview: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/…

New Yorker, “The case for Coolidge” (cached): https://webcache.googleusercontent.co…

NY Times, “Coolidge, the great refrainer”: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/17/bo…

NY Times, 1933 obituary for Coolidge: https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytim…

Atlantic, “Coolidge and depression”: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/…

Politico, “How Coolidge survived the Harding-era scandals”: https://www.politico.com/magazine/sto…

History, “Boston Police Strike of 1919”: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-h…

Coolidge letter written after death of his son: https://www.shapell.org/manuscript/pr…

October 6, 2020

QotD: Herbert Hoover and the Belgian relief program

Just as Hoover is preparing to rest on his laurels, he receives a cry for help. Germany has occupied and blockaded Belgium. The blockade prevents this tiny, heavily urban country from importing food, and the Belgians are starving. Germany needs its own food for its own armies, and is refusing to help. The Belgians order a thousand tons of grain from Britain, but when their representative comes to pick it up, Britain refuses to let them transport it, nervous at sending food into enemy-occupied territory. During tense negotiations, someone suggests using neutral power America as a go-between. But America is 5,000 miles away and busy with its own problems. So the US Ambassador to Britain asks his new best friend Herbert Hoover if he has any ideas.

Hoover invites Emile Francqui, a Belgian mining engineer he knows, to Britain. Together, they plan a Committee For The Relief of Belgium, intended not just to help transport the thousand tons of grain at issue, but to develop a long-term solution to the impending Belgian famine. Nothing like this has ever been tried before. Belgium has seven million people and almost no food. No government is offering to help, and they don’t have enough money to feed seven million people even for one day, let alone indefinitely. Hoover springs into action …

… by crushing all competing attempts to provide food for Belgium. He attacks the Rockefeller Foundation, which is trying to help, with a blitz of press coverage accusing it of various forms of insensitivity and interference, until it finally backs off. Then he gets to work on the government:

The letter bore several Hoover watermarks, beginning with its heavy load of facts and figures organized in point form. It noted that myriad relief committees were springing up both inside and outside of Belgium, and urged consolidation. “It is impossible to handle the situation except with the strongest centralization and effective monopoly, and therefore the two organizations [Hoover outside Belgium and Francqui inside it] will refuse to recognize any element except themselves alone.” The letter also contained Hoover’s usual autocratic and slightly paranoid demands for “absolute command” of his part of the enterprise.

Control attained, Hoover springs into action actually feeding Belgium. He launches one of the largest public relations campaigns the world has ever seen, sending letters to newspapers around the world asking for donations. He “urged reporters to investigate the famine conditions in Belgium and play up the ‘detailed personal horror stuff’. He personally arranged for a motion picture crew to capture footage of food lines in Brussels, and he hired famous authors, including Thomas Hardy and George Bernard Shaw, to plead for public support of the rescue effort.” He constantly telegrams his exasperated wife and children, now safely back in Palo Alto, demanding they raise more and more money from the West Coast elite.

He browbeats shipping conglomerates until they agree to ship his food for free, then browbeats railroads until they agree to carry it. By telegraph and letter he coordinates banks, railroads, docks, ships, and relief workers on both sides of the Atlantic. But that’s just the prelude. His real problem is the governments. Britain doesn’t want food shipped to Belgium, because right now the starving Belgians are Germany’s problem, and they don’t want to solve an enemy’s problem for them. But Germany also doesn’t want food shipped to Belgium, because the Belgians are resisting the occupation, and they figure starvation will make them more compliant. Shuttling back and forth across the North Sea, Hoover tries to get them to switch theories: Germany needs to think starving Belgians are their problem which it would be helpful to solve, and Britain needs to think starvation would make Belgians more compliant with the German occupation. In the end, both countries allow the shipments.

He goes on a fact-finding mission to Belgium, and managed to somehow offend everyone in the country that he is, at that very moment, saving from mass starvation […] By 1915, Hoover is, indeed, feeding millions of Belgians, indefinitely, using only private funding. He is also almost broke. Millions of Brits and Americans have given him contributions, from tycoons donating fortunes to ordinary people donating their wages, but it’s not enough. His expenses pass $5 million a month, which would be about $100 million today; all these bills are starting to catch up to him. In an act of supreme sacrifice, Hoover pledges his entire personal fortune as collateral for the Committee’s loans, then takes out more money. The grain shipments continue to flow, but his credit is at its end.

He continues beating on the doors of every government official he can find – British, German, American – demanding help. They all say their budgets are already occupied with the war effort. He begs them, lectures them, tells them that millions of people are doing to die. He goes all the way to the top, finagling an opportunity to meet with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Lloyd George later calls Hoover’s presentation “the clearest he had [ever] heard on any subject”, but he can offer only moral support.

What finally works is going to Germany and meeting with their top military brass. The brass are unimpressed; they still think that Belgium starving is as likely to help them as hinder. But the contact spooks top British officials, who agree to meet with Hoover again. Hoover feeds them carefully crafted lies, saying that the German brass have told him that British aid to Belgium would be a disaster to the Central Powers and so they, the Germans, are going to fund everything Hoover wants and more. “Oh no they don’t!” say the British, who promise to give Hoover even more funding than his imaginary German partners. The Committee for the Relief Of Belgium is finally back in the black. And what a black it is:

The scope and powers of the Committee For Relief of Belgium were mindboggling. Its shipping fleet flew its own flag. Its members carried special documents that served as CRB passports. Hoover himself was granted a form of diplomatic immunity by all belligerents, with the British permitting him to cross the Channel at will and the Germans providing him a document saying “this man is not to be stopped anywhere under any circumstances”. Hoover had privileged access to generals, diplomats, and ministers. He enjoyed personal contacts with the heads of warring governments. He negotiated treaties with the belligerents, advised them on policy, and delivered private messages among them. Great Britain, France, and Belgium would soon be turning over to him $150 million a year, enough to run a small country, and taking nothing for it beyond his receipt. As one British official observed, Hoover was running “a piratical state organized for benevolence.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

August 23, 2020

August 10, 2020

FDR’s “New Deal” and the Great Depression

The Great Depression began with the collapse of the stock market in 1929 and was made worse by the frantic attempts of President Hoover to fix the problem. Despite the commonly asserted gibe that Hoover tried laissez faire methods to address the economic crisis, he was a dyed-in-the-wool progressive and a life-long control freak (the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act which devasted world trade was passed in 1930). Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 election by promising to undo Hoover’s economic interventions, yet once in office he turned out to be even more of a control freak than Hoover. His economic and political plans made Hoover’s efforts seem merely a pale shadow.

For newcomers to this issue, “New Deal” is the term used to describe the various policies to expand the size and scope of the federal government adopted by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (a.k.a., FDR) during the 1930s.

And I’ve previously cited many experts to show that his policies undermined prosperity. Indeed, one of my main complaints is that he doubled down on many of the bad policies adopted by his predecessor, Herbert Hoover.

Let’s revisit the issue today by seeing what some other scholars have written about the New Deal. Let’s start with some analysis from Robert Higgs, a highly regarded economic historian.

… as many observers claimed at the time, the New Deal did prolong the depression. … FDR and Congress, especially during the congressional sessions of 1933 and 1935, embraced interventionist policies on a wide front. With its bewildering, incoherent mass of new expenditures, taxes, subsidies, regulations, and direct government participation in productive activities, the New Deal created so much confusion, fear, uncertainty, and hostility among businessmen and investors that private investment, and hence overall private economic activity, never recovered enough to restore the high levels of production and employment enjoyed in the 1920s. … the American economy between 1930 and 1940 failed to add anything to its capital stock: net private investment for that eleven-year period totaled minus $3.1 billion. Without capital accumulation, no economy can grow. … If demagoguery were a powerful means of creating prosperity, then FDR might have lifted the country out of the depression in short order. But in 1939, ten years after its onset and six years after the commencement of the New Deal, 9.5 million persons, or 17.2 percent of the labor force, remained officially unemployed.

Writing for the American Institute for Economic Research, Professor Vincent Geloso also finds that FDR’s New Deal hurt rather than helped.

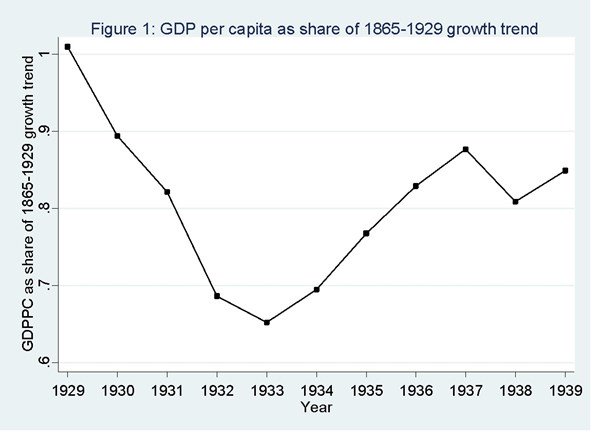

… let us state clearly what is at stake: did the New Deal halt the slump or did it prolong the Great Depression? … The issue that macroeconomists tend to consider is whether the rebound was fast enough to return to the trendline. … The … figure below shows the observed GDP per capita between 1929 and 1939 expressed as the ratio of what GDP per capita would have been like had it continued at the trend of growth between 1865 and 1929. On that graph, a ratio of 1 implies that actual GDP is equal to what the trend line predicts. … As can be seen, by 1939, the United States was nowhere near the trendline. … Most of the economic historians who have written on the topic agree that the recovery was weak by all standards and paled in comparison with what was observed elsewhere. … there is also a wide level of agreement that other policies lengthened the depression. The one to receive the most flak from economic historians is the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). … In essence, it constituted a piece of legislation that encouraged cartelization. By definition, this would reduce output and increase prices. As such, it is often accused of having delayed recovery. … other sets of policies (such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the National Labor Relations Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act) … were very probably counterproductive.

Here’s one of the charts from his article, which shows that the economy never recovered lost output during the 1930s.

July 23, 2020

QotD: Herbert Hoover in Australia and China

Hoover graduates Stanford in 1895 with a Geology degree. He plans to work for the US Geological Survey, but the Panic of 1895 devastates government finances and his job is cancelled. Hoover hikes up and down the Sierra Nevadas looking for work as a mining engineer. When none materializes, he takes a job an ordinary miner, hoping to work his way up from the bottom […]

After a few months, he finds a position as a clerk at a top Bay Area mining firm. One year later, he is a senior mining engineer. He is moving up rapidly – but not rapidly enough for his purposes. An opportunity arises: London company Berwick Moreing is looking for someone to supervise their mines in the Australian Outback. Their only requirement is that he be at least 35 years old, experienced, and an engineer. Hoover (22 years old, <1 year experience, geology degree only) travels to Britain, strides into their office, and declares himself their man. The executives “professed astonishment at Americans’ ability to maintain their youthful appearance” (Hoover had told them he was 36), but hire him and send him on an ocean liner to Australia.

[…]

After a year, Hoover is the most hated person in Australia, and also doing amazing. His mines are producing more ore than ever before, at phenomenally low prices. He scouts out a run-down out-of-the-way gold mine, realized its potential before anyone else, bought it for a song, and raked in cash when it ended up the richest mine in Australia. He received promotion after promotion.

Success goes to his head and makes him paranoid. He starts plotting against his immediate boss, Berwick Moreing’s Australia chief Ernest Williams. Though Williams didn’t originally bear him any ill will, all the plotting eventually gets to him, and he arranges for Hoover to be transferred to China. Hoover is on board with this, since China is a lucrative market and the transfer feels like a promotion. He travels first back to Stanford – where he marries his college sweetheart Lou Henry – and then the two of them head to China.

China is Australia 2.0. Hoover hates everyone in the country and they hate him back […] The same conflicts are playing itself out on the world stage, as Chinese resentment at their would-be-colonizers boils over into the Boxer Rebellion. A cult with a great name – “Society Of Righteous And Harmonious Fists” – takes over the government and encourages angry mobs to go around killing Westerners. Thousands of Europeans, including Herbert and Lou, barricade themselves in the partly-Europeanized city of Tientsin to make a final last stand.

In between dodging artillery shells, Hoover furiously negotiates property deals with his fellow besiegees. He argues that if any of them survive, it will probably because Western powers invade China to save them. That means they will soon be operating under Western law, and people who had already sold their mines to Western companies would be ahead of the game and avoid involuntary confiscation. Somehow, everything comes up exactly how Hoover predicts. US Marines arrived in Tientsin to liberate the city (Hoover marches with them as their local guide) and he is ready to collect his winnings.

Problem: it turns out that “Whatever, sure, you can have my gold mine, we’re all going to die anyway” is not legally ironclad. Hoover, enraged as he watches apparently done deals slip through his fingers, reaches new levels of moral turpitude. He offers the Chinese great verbal deals, then gives them contracts with terrible deals, saying that this is some kind of quaint foreign custom and if they just sign the contract then the verbal deal will be the legally binding one (this is totally false). At one point, he literally holds up a property office with a gun to get the deed to a mine he wants. Somehow, after consecutively scamming half the population of China, he ends up with the rights to millions of dollars worth of mines. Berwick Moreing congratulates him and promotes him to managing director. He and Lou sail for London to live the lives of British corporate bigshots.

As you might also predict, Hoover manages to offend everyone in Britain. Soon he is signing off on a “mutually agreeable”, “amicable” dismissal from Berwick Moreing. They agree to let him go on the condition that he does not compete with them – a promise he breaks basically instantly. He goes into banking, and his “bank” funds mining operations in a way indistinguishable from being a mining conglomerate. Eventually he abandons even this fig leaf, and just does the mining directly.

In other ways, his tens of millions of dollars are mellowing him out. Over his years in London, he develops hobbies besides making money and crushing people. He starts a family; he and Lou have two sons, Herbert Jr and Allen. He even hosts dinner parties, very gradually working on the skill of getting through an entire meal without mortally offending any guest…

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

July 16, 2020

QotD: The young Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover was born in 1874 to poor parents in the tiny Quaker farming community of West Branch, Iowa. His father was a blacksmith, his mother a schoolteacher. His childhood was strict. Magazines and novels were banned; acceptable reading material included the Bible and Prohibitionist pamphlets. His hobby was collecting oddly shaped sticks.

His father died when he is 6, his mother when he is 10. The orphaned Hoover and his two siblings are shuttled from relative to relative. He spends one summer on the Osage Indian Reservation in Oklahoma, living with an uncle who worked for the Department of Indian Affairs. Another year passes on a pig farm with his Uncle Allen. In 1885, he is more permanently adopted by his Uncle John, a doctor and businessman helping found a Quaker colony in Oregon. Hoover’s various guardians are dutiful but distant; they never abuse or neglect him, but treat him more as an extra pair of hands around the house than as someone to be loved and cherished. Hoover reciprocates in kind, doing what is expected of him but excelling neither in school nor anywhere else.

In his early teens, Hoover gets his first job, as an office boy at a local real estate company. He loves it! He has spent his whole life doing chores for no pay, and working for pay is so much better! He has spent his whole life sullenly following orders, and now he’s expected to be proactive and figure things out for himself! Hoover the mediocre student and all-around unexceptional kid does a complete 180 and accepts Capitalism as the father he never had.

His first task is to write some newspaper ads for Oregon real estate. He writes brilliant ads, ads that draw people to Oregon from every corner of the country. But he learns some out-of-towners read his ads, come to town, stay at hotels, and are intercepted by competitors before they negotiate with his company. Of his own initiative, he rents several houses around town and turns them into boarding houses for out-of-towners coming to buy real estate, then doesn’t tell his competitors where they are. Then he marks up rent on the boarding houses and makes a tidy profit on the side. Everything he does is like this. When an especially acrimonious board meeting threatens to split the company, a quick-thinking Hoover sneaks out and turns off the gas to the building, plunging the meeting into darknes. Everyone else has to adjourn, the extra time gives cooler heads a change to prevail, and the company is saved. Everything he does is like this.

(on the other hand, he has zero friends and only one acquaintance his own age, who later describes him to biographers as “about as much excitement as a china egg”.)

Hoover meets all sorts of people passing through the Oregon frontier. One is a mining engineer. He regales young Herbert with his stories of traveling through the mountains, opening up new sources of minerals to feed the voracious appetite of Progress. This is the age of steamships, skyscrapers, and railroads, and to the young idealistic Hoover, engineering has an irresistible romance. He wants to leave home and go to college. But he worries a poor frontier boy like him would never fit in at Harvard or Yale. He gets a tip – a new, tuition-free university might be opening in Palo Alto, California. If he heads down right away, he might make it in time for the entrance exam. Hoover fails the entrance exam, but the new university is short on students and decides to take him anyway.

Herbert Hoover is the first student at Stanford. Not just a member of the first graduating class. Literally the first student. He arrives at the dorms two months early to get a head start on various money-making schemes, including distributing newspapers, delivering laundry, tending livestock, and helping other students register. He would later sell some of these businesses to other students and start more, operating a constant churn of enterprises throughout his college career. His academics remain mediocre, and he continues to have few friends – until he tries out for the football team in sophomore year. He has zero athletic talent and fails miserably, but the coach (whose eye for talent apparently transcends athletics) spots potential in Hoover and asks him to come on as team manager. In this role, Hoover is an unqualified success. He turns the team’s debt into a surplus, and starts the Big Game – a UC Berkeley vs. Stanford football match played on Thanksgiving which remains a beloved Stanford football tradition.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

April 20, 2020

The four distinct phases of the Great Depression in the United States

An older post from Lawrence W. Reed at the Foundation for Economic Education outlines the low points of the Great Depression and debunks a few widely held myths about that cataclysmic economic era:

Phase 1, the Federal Reserve and the end of the Roaring 20’s:

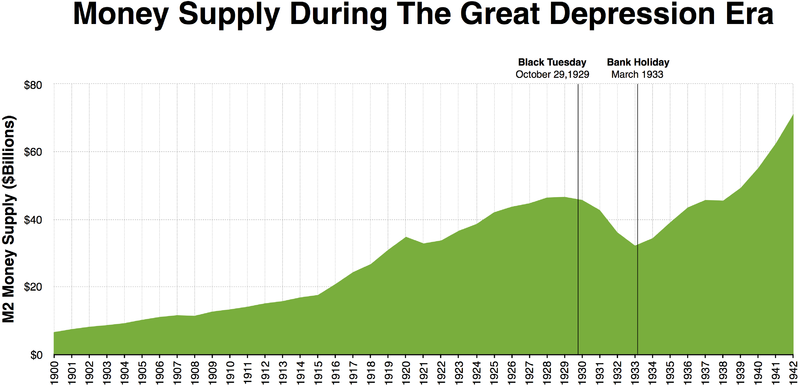

One of the most thorough and meticulously documented accounts of the Fed’s inflationary actions prior to 1929 is America’s Great Depression by the late Murray Rothbard. Using a broad measure that includes currency, demand and time deposits, and other ingredients, Rothbard estimated that the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply by more than 60 percent from mid-1921 to mid-1929. The flood of easy money drove interest rates down, pushed the stock market to dizzy heights, and gave birth to the “Roaring Twenties.”

By early 1929, the Federal Reserve was taking the punch away from the party. It choked off the money supply, raised interest rates, and for the next three years presided over a money supply that shrank by 30 percent. This deflation following the inflation wrenched the economy from tremendous boom to colossal bust.

The “smart” money — the Bernard Baruchs and the Joseph Kennedys who watched things like money supply — saw that the party was coming to an end before most other Americans did. Baruch actually began selling stocks and buying bonds and gold as early as 1928; Kennedy did likewise, commenting, “only a fool holds out for the top dollar.”

Phase 2, Hoover’s interventions and the disaster of Smoot-Hawley:

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot in April 1929, shortly before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives.

Library of Congress photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Unemployment in 1930 averaged a mildly recessionary 8.9 percent, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. It shot up rapidly until peaking out at more than 25 percent in 1933. Until March 1933, these were the years of President Herbert Hoover — the man that anti-capitalists depict as a champion of noninterventionist, laissez-faire economics.

Did Hoover really subscribe to a “hands off the economy,” free-market philosophy? His opponent in the 1932 election, Franklin Roosevelt, didn’t think so. During the campaign, Roosevelt blasted Hoover for spending and taxing too much, boosting the national debt, choking off trade, and putting millions of people on the dole. He accused the president of “reckless and extravagant” spending, of thinking “that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible,” and of presiding over “the greatest spending administration in peacetime in all of history.” Roosevelt’s running mate, John Nance Garner, charged that Hoover was “leading the country down the path of socialism.” Contrary to the modern myth about Hoover, Roosevelt and Garner were absolutely right.

The crowning folly of the Hoover administration was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed in June 1930. It came on top of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which had already put American agriculture in a tailspin during the preceding decade. The most protectionist legislation in U.S. history, Smoot-Hawley virtually closed the borders to foreign goods and ignited a vicious international trade war. Professor Barry Poulson notes that not only were 887 tariffs sharply increased, but the act broadened the list of dutiable commodities to 3,218 items as well.

Officials in the administration and in Congress believed that raising trade barriers would force Americans to buy more goods made at home, which would solve the nagging unemployment problem. They ignored an important principle of international commerce: trade is ultimately a two-way street; if foreigners cannot sell their goods here, then they cannot earn the dollars they need to buy here.

Phase 3, FDR and the New Deal:

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election in a landslide, collecting 472 electoral votes to just 59 for the incumbent Herbert Hoover. The platform of the Democratic Party whose ticket Roosevelt headed declared, “We believe that a party platform is a covenant with the people to be faithfully kept by the party entrusted with power.” It called for a 25 percent reduction in federal spending, a balanced federal budget, a sound gold currency “to be preserved at all hazards,” the removal of government from areas that belonged more appropriately to private enterprise, and an end to the “extravagance” of Hoover’s farm programs. This is what candidate Roosevelt promised, but it bears no resemblance to what President Roosevelt actually delivered.

In the first year of the New Deal, Roosevelt proposed spending $10 billion while revenues were only $3 billion. Between 1933 and 1936, government expenditures rose by more than 83 percent. Federal debt skyrocketed by 73 percent.

[…] in 1935 the Works Progress Administration came along. It is known today as the very government program that gave rise to the new term, “boondoggle,” because it “produced” a lot more than the 77,000 bridges and 116,000 buildings to which its advocates loved to point as evidence of its efficacy. The stupefying roster of wasteful spending generated by these jobs programs represented a diversion of valuable resources to politically motivated and economically counterproductive purposes.

The American economy was soon relieved of the burden of some of the New Deal’s excesses when the Supreme Court outlawed the NRA in 1935 and the AAA in 1936, earning Roosevelt’s eternal wrath and derision. Recognizing much of what Roosevelt did as unconstitutional, the “nine old men” of the Court also threw out other, more minor acts and programs which hindered recovery.

Phase 4, the Wagner Act:

The stage was set for the 1937–38 collapse with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 — better known as the Wagner Act and organized labor’s “Magna Carta.” […] Armed with these sweeping new powers, labor unions went on a militant organizing frenzy. Threats, boycotts, strikes, seizures of plants, and widespread violence pushed productivity down sharply and unemployment up dramatically. Membership in the nation’s labor unions soared; by 1941 there were two and a half times as many Americans in unions as in 1935.

[…]

Higgs draws a close connection between the level of private investment and the course of the American economy in the 1930s. The relentless assaults of the Roosevelt administration — in both word and deed — against business, property, and free enterprise guaranteed that the capital needed to jumpstart the economy was either taxed away or forced into hiding. When Roosevelt took America to war in 1941, he eased up on his antibusiness agenda, but a great deal of the nation’s capital was diverted into the war effort instead of into plant expansion or consumer goods. Not until both Roosevelt and the war were gone did investors feel confident enough to “set in motion the postwar investment boom that powered the economy’s return to sustained prosperity.”

October 18, 2019

The State of the US is Depressing | BETWEEN 2 WARS I 1933 Part 2 of 3

TimeGhost History

Published 17 Oct 2019The American economy is in a state of despair. Mass unemployment and poverty sweep the lands. In 1933, a new President is elected, promising to change things for the better. His name is Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Subscribe to our World War Two series: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwo…

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel and Spartacus Olsson

Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Wieke Kapteijns

Sound design: Marek KaminskiColorized pictures by Norman Steward, Daniel Weiss and Joram Appel.

Sources:

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

12 minutes ago (edited)

If you’re new here, you might not be familiar with Indy Neidell and his other work. Not only are we doing “Between Two Wars”, on the events and years leading up to World War Two (of which this video is a part), also we’re covering World War Two in realtime week-by-week, exactly 79 years after it all happened. We have now entered the second year of the war. If you haven’t already, check out the World War Two Channel for what maybe one day will become the most complete account of The Second World War: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwoCheers,

Joram

July 27, 2019

The US Economy is About to Crash Hard | Between 2 Wars | 1929 Part 1 of 3

TimeGhost History

Published on 25 Jul 2019In 1929 it’s been nothing but growth for the US economy for years, at least if you judge by the New York Stock Exchange. But all that glitters is not gold, and when the gilding comes off this bubble it sinks like a lead ballon.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Produced and directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound Mix by: Iryna DulkaArchive by: Reuters/Screenocean http://www.screenocean.com

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

3 hours ago (edited)

Now… ladies and gents – this is not a video about 2019 and we are not making any political statements. We know that some of you love making parallels between the present day and historical events. Although we can learn from history, try to remember that the circumstances were very different. Others among you feel it appropriate to extend partisan conflicts backwards and make out our videos, or events in the videos as partisan statements or issues. First of all we simply don’t do that, we just relate the events and the circumstances as factually as possible with the best possible sources. Second of all it is pointless to look for the 2019 partisan left/right divide according to party lines in events that happened 90 years ago. There’s just no comparison as both reality, and political parties have gone through so much change that the members of the same party, from today and then would probably disagree so vehemently on so many points the they would not even understand each other. So please, try your best to not go off on partisan rants, as it distracts form the actual historical issues at hand

September 28, 2018

The staunch Progressive dismissal of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge

In Richard Epstein’s review of Jill Lepore’s recent book These Truths: A History of the United States, there’s some interesting discussion of the Harding and Coolidge administrations:

Lepore’s narrative of this period begins with President Warren Harding, who, she writes, “in one of the worst inaugural addresses ever delivered,” argued, in his own words, “for lightened tax burdens, for sound commercial practices, for adequate credit facilities, for sympathetic concern for all agricultural problems, for the omission of unnecessary interference of Government with business, for an end to Government’s experiment in business, for more efficient business in Government, and for more efficient business in Government administration.” Harding’s sympathetic reference of farmers is a bit out of keeping with the rest of his remarks. Indeed, farmers had already been a protected class before 1920, and the situation only got worse when Franklin Roosevelt’s administration implemented the Agricultural Adjustment Acts of the 1930s, which cartelized farming. But for all her indignation, Lepore never explains what is wrong with Harding’s agenda. She merely rejects it out of hand, while mocking Harding’s conviction.

Given her doggedly progressive premises, Lepore may have predicted a calamitous meltdown in the American economy under Harding, but exactly the opposite occurred. Harding appointed an exceptionally strong cabinet that included as three of its principal luminaries Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, Andrew Mellon as Secretary of Treasury, and Herbert Hoover as the ubiquitous Secretary of Commerce, with a portfolio far broader than that position manages today. And how did they perform? Lepore does not mention that Harding coped quickly and effectively with the serious recession of 1921 by refusing to follow Hoover’s advice for aggressive intervention. Instead, Harding initiated powerful recovery by slashing the federal budget in half and reducing taxes across the board. Both Roosevelt and Obama did far worse in advancing recovery with their more interventionist efforts.

To her credit, Lepore notes the successes of Harding’s program: the rise of industrial production by 70 percent, an increase in the gross national product by about 40 percent, and growth in per capita income by close to 30 percent between 1922 and 1928. But, she doesn’t seem to understand why that recovery was robust, especially in comparison with the long, drawn-out Roosevelt recession that lingered on for years when he adopted the opposite policy of extensive cartelization and high taxes through the 1930s.

Lepore is on sound ground when she attacks Harding and Coolidge for their 1920s legislation that isolated the American economy from the rest of the world. The Immigration Act of 1924 responded to nativist arguments by seriously curtailing immigration from Italy and Eastern Europe, subjecting millions to the ravages of the Nazis a generation later. Harding and Coolidge also increased tariffs on imports during this period. What Lepore never quite grasps is that any critique of these actions rests most powerfully on the classical liberal worldview that she rejects. Indeed, Harding and Coolidge exhibited the same intellectual confusion that today animates Donald Trump, who gets high marks for supporting deregulation and tax reductions at home, while simultaneously indulging in unduly restrictive immigration policies and mercantilist trade wars abroad. Analytically, however, the same pro-market policies should control both domestically and abroad. Hoover never got that message — as president, he signed the misguided Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 that sharply reduced the volume of international trade to the detriment of both the United States and all of its trading partners, which helped turn what had been a short-term stock market downturn in 1929 into the enduring Great Depression of the 1930s.