Rex Krueger

Published 28 Oct 2020Learn about the famous infill planes of Scotland and England. Do they deliver on the hype?

More video and exclusive content: http://www.patreon.com/rexkrueger

Links from this video:

Hans Bruner’s Book on Infills (affiliate): https://amzn.to/3mlwXpj

(It’s $42.00, which is more than I remembered when I called it “reasonably priced.”)

Patrick Leach, renowned tool dealer: http://supertool.com/oldtools.htm

(READ the page and sign up for the email list to see what Patrick is selling. The list comes out on the 1st of each month. I have no affiliation with Patrick and I pay full retail for anything I get from him.)

Mortise and Tenon Magazine: https://www.mortiseandtenonmag.com/

(No affiliation.)Sign up for Fabrication First, my FREE newsletter: http://eepurl.com/gRhEVT

Wood Work for Humans Tool List (affiliate):

*Cutting*

Gyokucho Ryoba Saw: https://amzn.to/2Z5Wmda

Dewalt Panel Saw: https://amzn.to/2HJqGmO

Suizan Dozuki Handsaw: https://amzn.to/3abRyXB

(Winner of the affordable dovetail-saw shootout.)

Spear and Jackson Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/2zykhs6

(Needs tune-up to work well.)

Crown Tenon Saw: https://amzn.to/3l89Dut

(Works out of the box)

Carving Knife: https://amzn.to/2DkbsnM

Narex True Imperial Chisels: https://amzn.to/2EX4xls

(My favorite affordable new chisels.)

Blue-Handled Marples Chisels: https://amzn.to/2tVJARY

(I use these to make the DIY specialty planes, but I also like them for general work.)*Sharpening*

Honing Guide: https://amzn.to/2TaJEZM

Norton Coarse/Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/36seh2m

Natural Arkansas Fine Oil Stone: https://amzn.to/3irDQmq

Green buffing compound: https://amzn.to/2XuUBE2*Marking and Measuring*

Stockman Knife: https://amzn.to/2Pp4bWP

(For marking and the built-in awl).

Speed Square: https://amzn.to/3gSi6jK

Stanley Marking Knife: https://amzn.to/2Ewrxo3

(Excellent, inexpensive marking knife.)

Blue Kreg measuring jig: https://amzn.to/2QTnKYd

Round-head Protractor: https://amzn.to/37fJ6oz*Drilling*

Forstner Bits: https://amzn.to/3jpBgPl

Spade Bits: https://amzn.to/2U5kvML*Work-Holding*

Orange F Clamps: https://amzn.to/2u3tp4X

Screw Clamp: https://amzn.to/3gCa5i8Get my woodturning book: http://www.rexkrueger.com/book

Follow me on Instagram: @rexkrueger

October 29, 2020

The Legendary Scottish Infill Plane

October 22, 2020

When England “Londonized”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at changes in urbanization in England from the Middle Ages onward and the astonishing growth of London in particular:

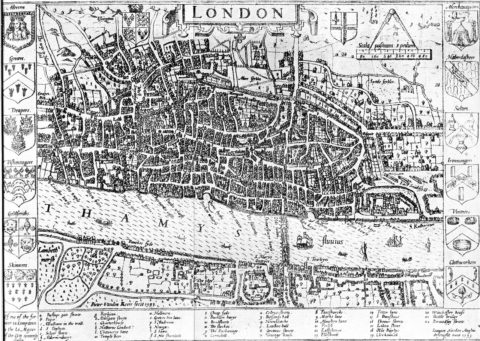

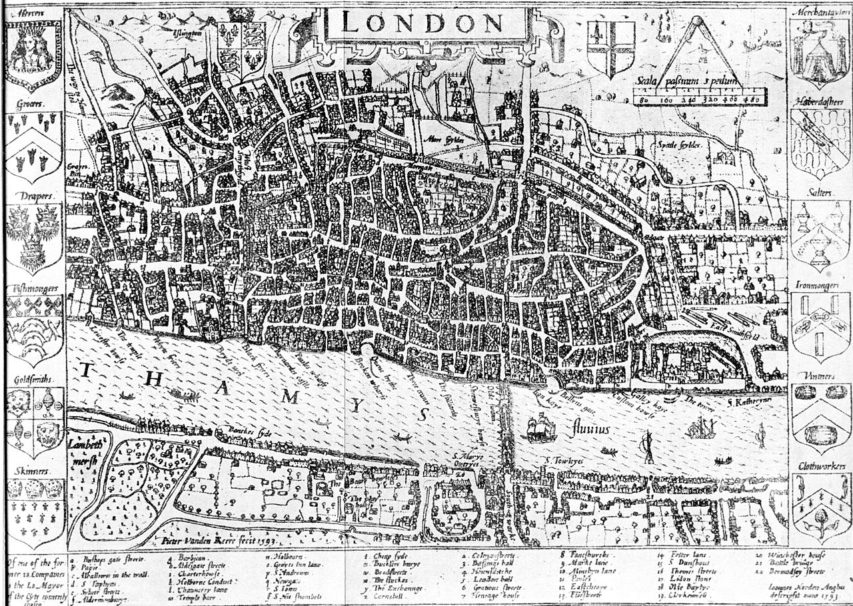

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

We must thus imagine pre-modern England as a land of tens of thousands of teeny tiny villages, each having no more than a couple of hundred people, which were in turn served by hundreds of slightly larger market towns of no more than a few hundred inhabitants, and with only a handful of regional centres of more than a few thousand people. By the 1550s, the country’s population had still not recovered to its pre-Black Death peak, and still only about 4% of the population lived in cities. London alone accounted for about half of that, with approximately 50-70,000 people (about five times the size of its closest rival, Norwich). So after a couple of centuries of recovery, London was only a little past its medieval peak.

But over the following century and a half, things began to change. At first glance, England’s continued population growth was unremarkable. By 1700, its overall population had finally reached and even surpassed the medieval 5 million barrier, despite the ravages of civil war. This was, perhaps, to be expected, with a little additional agricultural productivity allowing it to surpass the previous record. But the composition of that population had changed radically, largely thanks to the extraordinary growth of London. England’s overall population had not only recovered, but now 16% of them lived in cities of over 5,000 inhabitants — over two thirds of whom lived in London alone. Rather than simply urbanise, England londonised. By 1700, the city was nineteen times the size of second-place Norwich — even though Norwich’s population had more or less tripled.

London had, by 1700, thus risen from obscurity to become one of the largest cities in Europe. At an estimated 575,000 people, it was rivalled in Europe only by Paris and Constantinople, both of which had been massive for centuries. And although by modern standards it was still rather small, it could at least now be comfortably called a city — more or less on par with the populations of modern-day Glasgow or Baltimore or Milwaukee.

During that crucial century and a half then, London almost single-handedly began to urbanise the country. Its eighteenth-century growth was to consolidate its international position, such that by 1800 the city was approaching a million inhabitants, and from the 1820s through to the 1910s was the largest city in the world. In the mid-nineteenth century England also finally overtook Holland in terms of urbanisation rates, as various other cities also came into their own. But this was all just the continuation of the trend. London’s growth from 1550 to 1700 is the phenomenon that I think needs explaining — an achievement made all the more impressive considering how many of its inhabitants were dropping dead.

Throughout that period, urban death rates were so high that it required waves upon waves of newcomers from the countryside to simply keep the population level, let alone increase it. London was ridden with disease, crime, and filth. Not to mention the occasional mass death event. The city lost over 30,000 souls — almost of a fifth of its population — in the plague of 1603 (which was apparently exacerbated by many thousands of people failing to social distance for the coronation of James I), followed by the loss of a fifth again — 41,000 deaths — in the plague of 1625, and another 100,000 deaths — by now almost a quarter of the city’s population — in 1665. And yet, between 1550 and 1700 its population still managed to increase roughly tenfold.

I’ve been hard-pressed to find an earlier, similarly rapid rise to the half-a-million mark that was not just a recovery to a pre-disaster population or simply the result of an empire’s seat of government being moved. Chang’an, Constantinople, Ctesiphon, Agra, Edo, for example — all owed their initial, massive populations to an administrative change (often accompanied by a degree of forcible relocation), and all then grew fairly gradually up to or beyond half a million. As for a very long-term capital like Rome, it seems to have taken about three or four centuries to achieve the increases that London managed in just one and a half (though bear in mind just how rough and ready our estimates of ancient city populations are — our growth guesstimate for Rome is almost entirely based on the fact that the water supply system roughly doubled every century before its supposed peak). The rapidity of London’s rise from obscurity may thus have been unprecedented in human history — and was certainly up there with the fastest growers — though we’ll likely never know for sure.

But how? I can think of a multitude of factors that may have helped it along, but I find that each of them — even when considered altogether — aren’t quite satisfactory.

October 19, 2020

A bowyer talks about authentic longbows

Lindybeige

Published 10 Sep 2016Shot in Visby. I talk to Swedish bowyer Henrik Thurfjell about bows, asking stupid questions so that he sounds comparatively clever.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/LindybeigeHe talks about wood, of hunting, of string, and of bear fat. Many people in the comments have suggested exotic meanings for the mark on the side of the yew bow. The comparatively mundane truth is that the symbol is a combination of the Norse runes for H and T – the bowyer’s initials.

Thanks to Johan Käll for showing me round the re-enactors’ camp.

Picture credits:

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Mary Rose Trust – Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Mary Rose Trust – Mary Rose Trust – official webpage, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By Own scan. Photo by Gerry Bye. Original by Anthony Anthony. – Anthony Roll as reproduced in The Anthony Roll of Henry VIII’s Navy: Pepys Library 2991 and British Library Additional MS 22047 With Related Documents ISBN 0-7546-0094-7, p. 42., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…

By the Mary Rose Trust, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index…Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Lindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

website: www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

October 1, 2020

English lead and the European markets of the 1600s

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the meteoric rise in lead production in England and Wales from the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII to the Thirty Years’ War in Europe:

The well-preserved ruins of Fountains Abbey, a Cistercian monastery near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Founded in 1132 and dissolved by order of King Henry VIII in 1539. It is now owned by the Royal Trust as part of Studley Royal Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Photo by Admiralgary via Wikimedia Commons.

In the early sixteenth century, England was a minor producer of the stuff. It was widespread and cheap enough to be used for roofing buildings (unlike much of the rest of Europe, where copper was preferred), but the country never produced more than a few hundred tons per year. It didn’t really need to. Like stone in [the game] Dawn of Man, you could amass a stockpile and not worry too much about any leaky bucket problems [where stockpiles need to be replenished due to wastage or other “drains”]. The lead in roofs could always be recycled, and hardly any more was needed for pipes or cisterns. The vast majority of the demand came from Germany, and then the New World, where it was used to extract silver from copper ore. Even this dissipated in the mid-sixteenth century, when the New World silver mines began to switch to using mercury instead.

Yet by 1600, England was producing about 3,000 tons of lead a year, up from just 300 in the 1560s. By 1700, it was producing two thirds of Europe’s lead — a whopping 20,000 tons a year. How?

Unlike copper or iron, there is no evidence that lead mining or processing techniques were imported. If anything, they seem to have emerged from the Mendips, in Somerset, where production costs fell with the introduction of furnace smelting in the 1540s. As well as raising the extraction rates from the ore coming up from the mines, the new furnaces allowed previously unusable ores — found in the easily-accessible waste tips of old mining camps — to be smelted after some simple sifting. Unfortunately, we don’t have a clear idea of who was responsible for the innovation.

Yet the source of England’s supremacy was really, at first, religious. Following the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in the 1530s, the melting down of their roofs dumped some 12,000 tons of lead onto England’s markets — at least a year’s worth of Europe’s entire output. Although the immediate effect was to annihilate England’s own lead industry, the medium-term effect was to send the other European producers into disarray. By the 1580s, once the stockpile had depleted, England’s lead producers were among the only ones left standing. The sale of monastic lead ensured that the English retained a foothold in foreign markets, while the cost-saving innovations then gave them the competitive edge. These factors explain, at least, England’s eventual hold over the European lead market.

But there was yet another phenomenon responsible for the industry’s massively increased scale: the development of hand-held firearms. Gunpowder technology was of course centuries old, but cannon had largely fired balls made of stone or cast iron. Muskets and pistols, however, used bullets made of lead. With the proliferation of the weapons over the course of the seventeenth century, lead thus acquired a major leaky bucket problem. Bullets were too costly to recycle, leading to an estimated fifth of Europe’s annual production of lead disappearing every year — a wastage that only increased as armies grew, weapons’ rate of fire improved, and the continent experienced extraordinary violence. Europe lost an estimated fifth of its population to the Thirty Years’ War, and England itself succumbed to civil strife.

England’s lead industry thus had to drastically increase its production just to maintain Europe’s stock of lead, let alone increase it. It was from soldiers entering the fray, to trade bullets across sodden fields, that it owed its extraordinary success.

September 18, 2020

From innovation to absolutism — English inventors and the Divine Right of Kings

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at how innovations during the late Tudor and Stuart eras sometimes bolstered the monarchy in its financial battles with Parliament (which, in turn, eventually led to actual battles during the English Civil War):

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

The various schemes that innovators proposed — from finding a northeast passage to China, to starting a brass industry, to colonising Virginia, or boosting the fish industry by importing Dutch salt-making methods — all promised to benefit the public. They were to support the “common weal”, or commonwealth. And to a certain extent, many projects did. The historian Joan Thirsk did much pioneering work in the 1970s to trace the impact of various technological or commercial projects, revealing that even something as mundane as growing woad, for its blue dye, could have a dramatic impact on local economies. With woad, the income of an ordinary farm labouring household might be almost doubled, for four months in the year, by employing women and children. In the late 1580s, the 5,000 or so acres converted to woad-growing in the south of England likely employed about 20,000 people. That may seem small today, but at a time when the population of a typical market town was a paltry 800 people, even a few hundred acres of woad being cultivated here or there might draw in workers from across the whole region. In the mid-sixteenth century, even the entire population of London had only been about 50-70,000. As Thirsk discovered, innovative projectors also sometimes fulfilled their other public-spirited promises, for example by creating domestic substitutes for costly imported goods, or securing the supplies of strategic resources.

But the ideal of benefiting the commonwealth could also, all too frequently, be elided with serving the interests of the Crown. Projectors might promise the monarch a direct share of an invention’s profits, or that a stimulated industry would result in higher income from tariffs or excise taxes. Increasingly, they proposed schemes that were almost entirely focused on maximising state revenue, with little evidence of new technology. They identified “abuses” in certain industries — at this remove, it’s difficult to tell if these justifications were real — and asked for monopolies over them in order to “regulate” them, then making money by selling licences. Last week I mentioned patents over alehouses, and on playing cards. They also offered to increase the income from the Crown’s property, for example by finding so-called “concealed lands” — lands that had been seized during the Reformation, but which through local resistance or corruption had ostensibly not been paying their proper rents. The projectors would take their share of the money they identified as “missing”. And they proposed enforcing laws, especially if the punishments involved levying fines or confiscating property. The projectors offered to find the lawbreakers and prosecute them, after which they’d take their share of the financial punishments.

Projectors thus came to present themselves as state revenue-raisers and enforcers, circumventing all of the traditional constraints on the monarch’s money and power. They provided an alternative to Parliaments, as well as to city corporations and guilds, in raising money and propagating their rule. Taking it a step further, projectors offered the tantalising possibility that kings like James I and Charles I might rule through proclamation and patents alone, without having to answer to anybody. They thus experimented with absolutism for much of 1610-40, only occasionally being forced to call Parliament for as briefly as possible when the pressing financial demands of war intervened.

In the process, with the growing multitude of projects — a few bringing technological advancement, but many merely lining the pockets of courtier and king — the designation “projector” became mud. It was as if, today, the Queen were to use her prerogative to grant a few of her courtiers monopolies on collecting all traffic fines, or litter penalties, to be rewarded solely on commission. Or if she were to award an unscrupulous private company the right to award all alcohol-selling licences (perhaps on the basis that underage drinking was becoming common). The country would soon be awash with hidden speed cameras and incognito litter wardens, and the price of alcohol would go through the roof. The people responsible would not be popular. A recent book by economic historian Koji Yamamoto meticulously charts the changing public perceptions of projects, describing the ways in which innovators then struggled, for decades, to regain the public’s trust.

September 5, 2020

Beginning the transition from personal rule to the modern bureaucratic state

Anton Howes discusses some of the issues late Medieval rulers had which in some ways began the ascendency of our modern nation state with omnipresent bureaucratic oversight of everyone and everything:

… the bureaucratic state of today, with its officials involving themselves with every aspect of modern life, is a relatively recent invention. In a world without bureaucracy, when state capacity was relatively lacking, it’s difficult to see what other options monarchs would have had. Suppose yourself transported to the throne of England in 1500, and crowned monarch. Once you bored of the novelty and luxuries of being head of state, you might become concerned about the lot of the common man and woman. Yet even if you wanted to create a healthcare system, or make education free and universal to all children, or even create a police force (London didn’t get one until 1829, and the rest of the country not til much later), there is absolutely no way you could succeed.

King James I (of England) and VI (of Scotland)

Portrait by Daniel Myrtens, 1621 from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.For a start, you would struggle to maintain your hold on power. Fund schools you say? Somebody will have to pay. The nobles? Well, try to tax them — in many European states they were exempt from taxation — and you might quickly lose both your throne and your head. And supposing you do manage to tax them, after miraculously stamping out an insurrection without their support, how would you even begin to go about collecting it? There was simply no central government agency capable of raising it. Working out how much people should pay, chasing up non-payers, and even the physical act of collection, not to mention protecting that treasure once collected, all takes substantial manpower. Not to mention the fact that the collecting agents will likely siphon most of it off to line their own pockets.

[…]

It was not until 1689, when there was a coup, that an incoming ruler allowed the English parliament to sit whenever it pleased. Before that, it was convened only at the whim of the ruler, and dispersed even at the slightest provocation. In 1621, for example, when James I was planning to marry his heir to a Spanish princess, Parliament sent him a petition asserting their right to debate the matter. Upon hearing of it, he called for the official record of parliamentary proceedings, personally ripped out the page with the offending vote, and promptly dissolved the Parliament. The downside, of course, was that James could not then acquire any parliamentary subsidies.

Ruling was thus an intensely personal affair, of making deals and finding ways to circumvent deals you had inherited. Increasing your capabilities as a ruler – state capacity – was thus no easy task, as the typical ruler was stuck in an essentially medieval equilibrium. Imposing a policy costs money, but raising money involves imposing policy. Breaking out of this chicken-and-egg problem took centuries of canny leadership. The rulers who achieved it most would today seem hopelessly corrupt.

To gain extra cash without interference from Parliament, successive monarchs first asserted and then abused their ancient prerogative rights to grant monopolies over trades and industries. They eventually granted them to whomever was willing to pay, establishing monopolies over industries like gambling cards or alehouses under the guise of regulating unsavoury activities. They also sold off knighthoods and titles, and in 1670 Charles II even made a secret deal with the French that he would convert to Catholicism and attack the Protestant Dutch, all in exchange for cash. Anything to not have to call a potentially pesky Parliament. At times, the most effective rulers even resembled mob bosses. Take Elizabeth I’s anger when a cloth-laden merchant fleet bound for an Antwerp fair in 1559 was allowed to depart. Her order to stop them had not arrived in time, thus preventing her from extracting “loans” from the merchants while she still had their goods within her power.

September 4, 2020

How England used to vote

Learnhistory3

Published 1 May 2011Rowan Atkinson as Edmund BlackAdder in a sketch on the voting situation before 1832. Rotten boroughs and pocket boroughs etc

Script excerpt from BlackAdder Scripts:

At Mrs. Miggins’ home

E: Well, Mrs. Miggins, at last we can return to sanity. The hustings are

over, the bunting is down, the mad hysteria is at an end. After the

chaos of a general election, we can return to normal.M: Oh, has there been a general election, then, Mr. BlackAdder?

E: Indeed there has, Mrs. Miggins.

M: Oh, well, I never heard about it.

E: Well of course you didn’t; you’re not eligible to vote.

M: Well, why not?

E: Because virtually no-one is: women, peasants, (looks at Baldrick)

chimpanzees (Baldrick looks behind himself, trying to see the animal),

lunatics, Lords…B: That’s not true — Lord Nelson’s got a vote!

E: He’s got a boat, Baldrick. Marvelous thing, democracy. Look at

Manchester: population, 60,000; electoral roll, 3.M: Well, I may have the brain the size of a sultana…

E: Correct…

M: …but it hardly seems fair to me.

E: Of course it’s not fair — and a damn good thing too. Give the like of

Baldrick the vote and we’ll be back to cavorting druids, death by

stoning, and dung for dinner.B: Oh, I’m having dung for dinner tonight.

M: So, who are they electing when they have these elections?

E: Ah, the same old shower: fat tory landowners who get made MPs when

they reach a certain weight; raving revolutionaries who think that just

because they do a day’s work that somehow gives them the right to get

paid… Basically, it’s a right old mess. Toffs at the top, plebs at the

bottom, and me in the middle making a fat pile of cash out of both of them.M: Oh, you’d better watch out, Mr. BlackAdder; things are bound to change.

E: Not while Pitt the Elder’s Prime Minister they aren’t. He’s about as

effective as a catflap in an elephant house. As long as his feet are warm

and he gets a nice cup of milky tea in the sun before his morning nap,

he doesn’t bother anyone until his potty needs emptying.

August 31, 2020

Military Equipment of the Anglo Saxons and Vikings

Invicta

Published 19 Apr 2018Today we dive into the world of Early Medieval England to analyze the military equipment available to the warring Anglo Saxons and Vikings!

Support future documentaries: https://www.patreon.com/InvictaHistory

Twitter: https://twitter.com/InvictaHistoryDocumentary Credits:

Research: Invicta

Script: Invicta

Artwork: Osprey Publishing

Game: Total War Saga: Thrones of Britannia

Editing: Invicta

Music: Total War: Attila and Total War Battles: Kingdoms SoundtrackLiterary Sources

–Anglo-Saxon Thegn by Mark Harrison (Osprey Publishing)

–Viking Hersir 793–1066 AD by Mark Harrison (Osprey Publishing)

–Saxon, Viking and Norman by Terence Wise (Osprey Publishing)

August 22, 2020

John Cabot’s patent monopoly grant and the rise of the modern corporation

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the line of descent of modern corporate structures from the patent granted to John Cabot to explore (and exploit) a trade route to China:

The replica of John Cabot’s ship Matthew in Bristol harbour, adjacent to the SS Great Britain.

Photo by Chris McKenna via Wikimedia Commons.

I discussed last time [linked here] how the use of patent monopolies came to England in the sixteenth century. Since then, however, I’ve developed a strong hunch that the introduction of patent monopolies may also have played a crucial role in the birth of the business corporation. I happened to be reading Ron Harris’s new book, Going the Distance, in which he stresses the unprecedented constitutions of the Dutch and English East India Companies — both of which began to emerge in the closing years of the sixteenth century. Yet the first joint-stock corporation, albeit experimental, was actually founded decades earlier, in the 1550s. Harris mentions it as a sort of obscure precursor, and it wasn’t terribly successful, but it stood out to me because its founder and first governor was also one of the key introducers of patent monopolies to England: the explorer Sebastian Cabot.

As I mentioned last time, Cabot was named on one of England’s very first patents for invention — though we’d now say it was for “discovery” — in 1496. An Italian who spent much of his career serving Spain, he was coaxed back to England in the late 1540s to pursue new voyages of exploration. Indeed, he reappeared in England at the exact time that patent monopolies for invention began to re-emerge, after a hiatus of about half a century. In 1550, Cabot obtained a certified copy of his original 1496 patent and within a couple of years English policymakers began regularly granting other patents for invention. It started as just a trickle, with one 1552 patent granted to to some enterprising merchant for introducing Norman glass-making techniques, and a 1554 patent to the German alchemist Burchard Kranich, and in the 1560s had developed into a steady stream.

Yet Cabot’s re-certification of his patent is never included in this narrative. It’s a scarcely-noted detail, perhaps because he appears not to have exploited it. Or did he? I think the fact of his re-certification — a bit of trivia that’s usually overlooked — helps explain the origins of the world’s first joint-stock corporation.

Corporations themselves, of course, were nothing new. Corporate organisations had existed for centuries in England, and indeed throughout Europe and the rest of the world: officially-recognised legal “persons” that might outlive each and any member, and which might act as a unit in terms of buying, selling, owning, and contracting. Cities, guilds, charities, universities, and various religious organisations were usually corporations. But they were not joint-stock business corporations, in the sense of their members purchasing shares and delegating commercial decision-making to a centralised management to conduct trade on their behalves. Instead, the vast majority of trade and industry was conducted by partnerships of individuals who pooled their capital without forming any legally distinct corporation. Shares might be bought in a physical ship, or even in particular trading voyages, but not in a legal entity that was both ongoing and intangible. There were many joint-stock associations, but they were not corporations.

And to the extent that some corporations in England were related to trade, such as the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London, or the Company of Merchants of the Staple, they were not joint-stock businesses at all. They were instead regulatory bodies. These corporations were granted monopolies over the trade with certain areas, or in certain commodities, to which their members then bought licenses to trade on their own account. Membership fees went towards supporting regulatory or charitable functions — resolving disputes between members, perhaps supporting members who had fallen on hard times, and representing the interests of members as a lobby group both at home and abroad — but not towards pooling capital for commercial ventures. The regulated companies were thus more akin to guilds, or to modern trade unions or professional associations, rather than firms. Members were not shareholders, but licensees who used their own capital and were subject to their own profits and losses.

Before the 1550s, then, there had been plenty of unincorporated business associations that were joint-stock, and even more unincorporated associations that were not joint-stock. There had also been a few trade-related corporations that were not joint-stock. Sebastian Cabot’s innovation was thus to fill the last quadrant of that matrix: he created a corporation that would be joint-stock, in which a wide range of shareholders could invest, entrusting their capital to managers who would conduct repeated voyages of exploration and trade on their behalves.

August 20, 2020

Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury 1162-1170

Reverend Steve Morris tries to show why St. Thomas of Canterbury needs a “reboot” for modern eyes:

Stained glass showing the murder of St. Thomas at Canterbury on 29 December, 1170.

Wikimedia Commons.

It’s 850 years since that night when four knights murdered the Archbishop of Canterbury. It’s been a rocky old road for Thomas Becket despite hundreds of years as the poster-boy of the cult of saints which swept medieval England. His reputation, his legacy and his conduct have been filleted over the last few centuries and we are left with just a ghost of the man who, once upon a time, stood for all that was good.

It is a cautionary tale of historical revisionism, measuring yesterdays’ saints by today’s “standards” and assembling a set of half-truths to trash the reputation of England’s great, perhaps greatest, saint. It is high time he made a comeback – especially in these political times. After all, Becket was perhaps the greatest political martyr we have. Of course, there is always truth in just about any criticism. And Becket lays himself open. He was, to say the least, stubborn. He was a contrarian and he was reckless with his own safety. In an age of kingly power, it doesn’t do to embarrass the monarch.

The charge sheet does quickly stack up. Becket was a canny careerist (although you’d be hard pushed to find anyone of influence at the time who wasn’t). He seemed to have a death wish, or at least refused to listen to perfectly sensible advice on taking a more circumspect path. And his cause, seen through a certain lens, seems off-beam for modern times. He has been painted as standing for the ancient legal power of the church against a reforming king who began to kick-start Common Law. But of course, it’s never as simple as this.

But none of this was the real problem and none of it was what caused our great saint to be consigned to the historical dustbin. As is often the way, the problem comes down to background and class. Becket was born to only modestly well-off parents in London (he has always been London’s saint). His father was middle-class, and a merchant. Becket was “trade” by background and it was something he couldn’t shake off. But his rise was an astounding feat of defying gravity.

In an era of complex geopolitics and conflicts between pope and state Thomas rose through the ranks and became Archbishop of Canterbury. At first, he seemed like the king’s man, but relations soured. Becket and the king were entangled in a fight to the death, with the archbishop excommunicating various opponents and generally throwing his weight around.

His death was gruesome. Four knights ambushed him. He could have run or barricaded himself in the cathedral, but he told his followers that God’s house should not be made a fortress. He pushed one of his attackers. What followed was a flurry of sword-strokes to the head – one of which took his tonsured skull right off. The contemporaneous reports paint a ghastly picture of brain fluid and blood mixing freely on the cathedral floor. But it didn’t end there.

August 7, 2020

From Medieval Letters Patent to our modern patents, by way of Venice

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes traces the lines of descent from the Letters patent of the Middle Ages, through Venetian legal innovations, to what began to resemble our modern patent system:

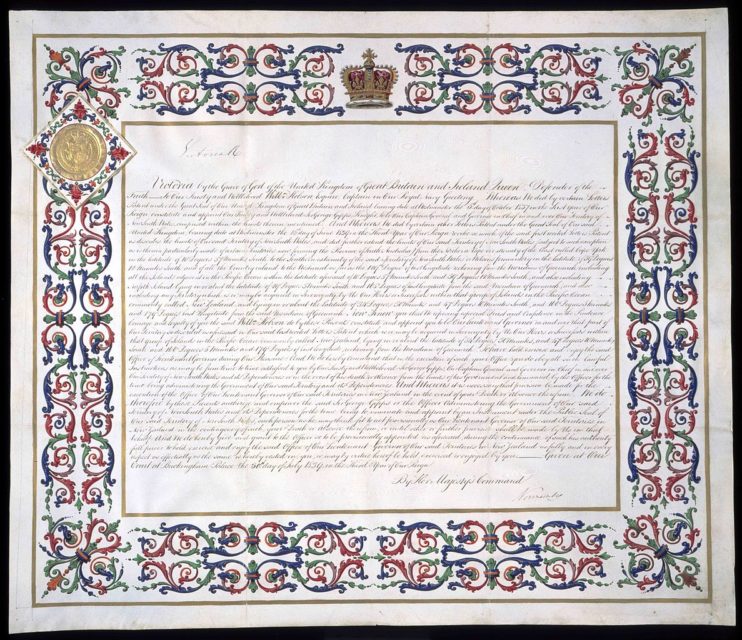

Letters Patent Issued by Queen Victoria, 1839

On 15 June 1839 Captain William Hobson was officially appointed by Queen Victoria to be Lieutenant Governor General of New Zealand. Hobson (1792 – 1842) was thus the first Governor of New Zealand. This position was renamed in 1907 as “Governor General”. Hobson arrived in New Zealand in late January 1840, and oversaw the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi only a few days later. By the end of 1840, New Zealand became a colony in its own right and Hobson moved the capital of the colony from the Bay of Islands to Auckland. He served as Governor until his death in 1842 after he suffered a stroke at the age of 49.

Constitutional Records group of Archives NZ via Wikimedia Commons.

Patents for invention — temporary monopolies on the use of new technologies — are frequently cited as a key contributor to the British Industrial Revolution. But where did they come from? We typically talk about them as formal institutions, imposed from above by supposedly wise rulers. But their origins, or at least their introduction to England, tell a very different story.

England’s monarchs had long used their prerogative powers to grant special dispensations by letters patent — that is, orders from the monarch that were open for all the public to see (think of the word patently, from the same root, which means openly or clearly). For the most part, such public proclamations had been used to grant titles of nobility, or to appoint people to positions in various official hierarchies — legal, religious, and governmental. And, of course, letters patent could be used to promote the introduction of new technologies.

[…]

Monopolies in general, of course, over particular trades or industries had been granted for centuries, by rulers all across Europe. They granted such privileges to groups of merchants, artisans, and city-dwellers, giving them rights to organise and regulate their own activities as guilds or as city corporations. Inherent to all such charters was the ability of the in-group to restrict competition from outsiders, at least within the confines of their city. And the ruler, in exchange for granting such privileges, typically received a share of the guild’s or corporation’s revenues. But such monopolies were very rarely given to individuals. When they were, it was often so unpopular as to be almost immediately overturned. And they were rarely used to encourage innovation.

With one exception: Italy. Throughout the fifteenth century, some Italian city guilds had begun to forbid their members from copying newly-invented patterns for silk and woollen cloth, effectively granting a monopoly over those patterns to the individual inventors. In Venice, a 50-year monopoly was granted in 1416 to one Franciscus Petri, of Rhodes, to introduce superior fulling mills. In Florence, the famous architect and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi was granted a monopoly in 1421 for a vessel he designed for transporting heavy loads of marble, in exchange for revealing the secrets of his design. The printing press was also introduced to Venice using such a privilege, with a 5-year monopoly granted in 1469 to Johannes of Speyer, though he died only a few months after receiving it. And these ad hoc grants were made with increasing frequency, such that in 1474 Venice legislated to make them more systematic, declaring that 10-year monopolies could be obtained for all new technologies, either invented or imported (though it continued to also grant ad hoc patents, with the terms and durations decided on a case-by-case basis as before). Under the 1474 law, Venice was soon granting patent monopolies to the introducers of various mills, pumps, dredges, textile machines, printing techniques, and even special kinds of lasagna. It granted over a hundred patents in the first half of the sixteenth century, with many more thereafter.

From Venice, the use of patent monopolies as an instrument of policy spread abroad, with the initiative coming from the would-be introducers of novelties themselves. In the mid-fifteenth century, for example, a French inventor who had acquired patents in Venice was also successfully lobbying for similar privileges from the archbishop of Salzburg, the duke of Ferrara, and the Hapsburg Holy Roman Emperor. The use of patent monopolies thus soon diffused to the rest of Italy, to Germany, and to the various dominions of the Spanish emperor — including Spain itself, its American colonies, and the Low Countries.

And, eventually, to England. But not in the way we might expect. In 1496, the Venetian explorer Zuan Chabotto (aka John Cabot) acquired a patent monopoly from Henry VII over the trade and products of any lands he was to discover — a legal procedure unlike anything that earlier English explorers had attempted (they had merely been granted licenses). Cabot’s grant even differed from the agreements made by Christopher Columbus with the Spanish crown, or by earlier explorers for the Portuguese. Columbus, for example, was effectively granted a patent of nobility — the hereditary titles of viceroy, admiral, and governor. He and the Portuguese explorers were direct agents of the crown, with military and justice-dispensing responsibilities over any newly conquered lands — a model derived from the Christian conquests of Muslim Iberia. Columbus effectively became a marcher lord, a custodian and defender of Spain’s new borderlands.

July 22, 2020

A brief look at the life of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s “main fixer”

Michael Coren discusses the career and reputation of Henry VIII’s powerful and capable Lord Chamberlain until he fell from favour and was executed in 1540:

Portrait of Thomas Cromwell, First Earl of Essex painted by Hans Holbein 1532-33.

From the Frick Collection via Wikimedia Commons.

The panoply of British history doesn’t include too many monsters. The nation was founded more on meetings than massacres, and other than the usual round of chronic blood-letting in the Middle Ages, and a civil war in the seventeenth-century, the English have left it to the French, the Russians, and the Germans to provide the mass murderers and the genuine villains. But if anyone was generally regarded as being unscrupulous, with a touch of the devil always around his character, it was Thomas Cromwell, the main fixer for Henry VIII in the 1530s, and according to the Oscar-winning movie A Man for all Seasons, the dark politician who had hagiographical Thomas More executed. For decades both on British television and in Hollywood epics it was this self-made man who was willing to smash the monasteries, torture innocent witnesses into giving false evidence, and assemble lies to have that nice Anne Boleyn beheaded.

This was the dictatorship of reputation. Historians provided the framework, and popular entertainment dressed it all up in countless Tudor biopics. But then it all began to change.

The first person to seriously challenge the caricature was himself a victim of lies and hatred. The revered Cambridge historian GR Elton was born Gottfried Rudolf Otto Ehrenberg, son of a German Jewish family of noted scholars, who fled to Britain shortly before the Holocaust. He’s also, by the way, the uncle of the comedian and writer Ben Elton. GR, Geoffrey Rudolph, was one of the dominant post-war historians, and insisted that modern Britain, with its secular democracy and parliamentary system, was very much the child of Thomas Cromwell the gifted administrator and political visionary.

So we had the Cromwell wars. On the one side were the traditionalist, often Roman Catholic, writers who insisted that Cromwell was a corrupt brute and a cruel tyrant; and the rival school that regarded him as the first modern leader of the country, setting it on a road that would distinguish it from the ancient regimes of the European continent. But there was more. While previous political leaders – the term “Prime Minister” didn’t develop until the early eighteenth-century – had sometimes been of relatively humble origins, and Cromwell’s mentor and predecessor Thomas Wolsey was the son of a butcher, they were invariably clerics. Cromwell wasn’t only from rough Putney on the edge of London, and the son of a blacksmith, but he was a layman, and someone who had lived abroad, even fought for foreign armies.

Here was have the embodiment of the great change: the autodidact who was multi-lingual, well travelled, reformed in his religion and politics, and prepared to rip the country out of its medieval roots. Yet no matter how many historians might believe and write this, the culture is notoriously difficult to change, and understandably indifferent to academics. Not, however, to novelists. And in 2009 the award-winning author Hilary Mantel published Wolf Hall, a fictional account of Cromwell’s life from 1500 to 1535. Three years later came the sequel, Bring Up the Bodies. Both books won the Man Booker Prize, an extraordinary achievement for two separate works. The trilogy was completed recently with The Mirror and the Light. The first two volumes were turned into an enormously successful stage play and a six-part television show. Forget noble academics working away in relative obscurity, this was sophisticated work watched and read by tens of millions of people. Cromwell was back.

“It is as a murderer that Cromwell has come down to posterity: who turned monks out on to the roads, infiltrated spies into every corner of the land, and unleashed terror in the service of the state”, wrote Mantel in the Daily Telegraph back in 2012. “If these attributions contain a grain of truth, they also embody a set of lazy assumptions, bundles of prejudice passed from one generation to the next. Novelists and dramatists, who on the whole would rather sensationalise than investigate, have seized on these assumptions to create a reach-me-down villain.”

Glorious Revolution | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 21 Jul 2015Sorry about the delay I’ve been without internet while I’ve moved apartment. And thanks for the 9,000 subs

Thanks to Xios, Alan Haskayne, Lachlan Lindenmayer, William Crabb, Derpvic, Seth Reeves and all my other Patrons. If you want to help out – https://www.patreon.com/Jabzy?ty=h

Please let me know if I’ve forgot to mention you, I’m a little disorganized without internet.

July 18, 2020

“Agglomerationists” today and in the Middle Ages

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes compares the views of today’s “urbanists” with the “agglomerationists” of the late Medieval period:

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

The other day, economic historian Tim Leunig tagged me into a comment on twitter with the line “intellectually I think the biggest change since settled agriculture was the idea that most people could live in cities and not produce food”. What’s interesting about that, I think, is the idea that this was not just an economic change, but an intellectual one. In fact, I’ve been increasingly noticing a sort of ideology, if one can call it that, which seemingly took hold in Britain in the late sixteenth century and then became increasingly influential. It was not the sort of ideology that manifested itself in elections, or even in factions, but it was certainly there. It had both vocal adherents and strenuous opponents, the adherents pushing particular policies and justifying them with reference to a common intellectual tradition. Indeed, I can think of many political and economic commentators who are its adherents today, whether or not they explicitly identify as such.

Today, the people who hold this ideology will occasionally refer to themselves as “urbanists”. They are in favour of large cities, large populations, and especially density. They believe strongly in what economists like to call “agglomeration effects” — that is, if you concentrate people more closely together, particularly in cities, then you are likely to see all sorts of benefits from their interactions. More ideas, more trade, more innovation, more growth.

Yet urbanism as a word doesn’t quite capture the full scope of the ideology. The group also heavily overlaps with natalists — people who think we should all have more babies, regardless of whether they happen to live in cities — and a whole host of other groups, from pro-immigration campaigners, to people setting up charter cities, to advocates of cheaper housing, to enthusiasts for mass transit infrastructure like buses, trams, or trains. The overall ideology is thus not just about cities per se — it seems a bit broader than that. Given the assumptions and aims that these groups hold in common, perhaps a more accurate label for their constellation of opinions and interests would be agglomerationism.

So much for today. What is the agglomerationist intellectual tradition? In the sixteenth century, one of the mantras that keeps cropping up is the idea that “the honour and strength of a prince consists in the multitude of the people” — a sentiment attributed to king Solomon. It’s a phrase that keeps cropping up in some shape or form throughout the centuries, and used to justify a whole host of agglomerationist policies. And most interestingly, it’s a phrase that begins cropping up when England was not at all urban, in the mid-sixteenth century — only about 3.5% of the English population lived in cities in 1550, far lower than the rates in the Netherlands, Italy, or Spain, each of which had urbanisation rates of over 10%. Even England’s largest city by far, London, was by European standards quite small. Both Paris and Naples were at least three times as populous (don’t even mention the vast sixteenth-century metropolises of China, or Constantinople).

Given their lack of population or density, English agglomerationists had a number of role models. One was the city of Nuremburg — through manufactures alone, it seemed, a great urban centre had emerged in a barren land. Another was France, which in the early seventeenth century seemed to draw in the riches to support itself through sheer exports. One English ambassador to France in 1609 noted that its “corn and grain alone robs all Spain of their silver and gold”, and warned that it was trying to create still new export industries like silk-making and tapestry weaving. (The English rapidly tried to do the same, though with less success.) France may not have been especially urban either, but Paris was already huge and on the rise, and the country’s massive overall population made it “the greatest united and entire force of any realm or dominion” in Christendom. Today, the population of France and Britain are about the same, but in 1600 France’s was about four times as large. Some 20 millions compared to a paltry 5. If Solomon was right, then England had a lot of catching up to do to even approach France in honour.

July 10, 2020

English Civil War | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 9 Mar 2015I cut quite a bit out to save time. I’ll try and do a video on the Protectorate or the Restoration soon.