TimeGhost History

Published 5 May 2025In early 1949, the Arab-Israeli War finally comes to an uneasy end. After brutal fighting, armistice talks in Rhodes redraw borders with a green pencil line, displacing hundreds of thousands and reshaping the Middle East. Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon reluctantly sign ceasefires, leaving core issues — Jerusalem, refugees, and recognition — unresolved. But can forced armistices really bring lasting peace, or is Palestine fated to endless conflict?

(more…)

May 6, 2025

1949: How the Arab-Israeli War Ended – W2W 27

April 15, 2025

How the UN Plan Tore Palestine Apart – W2W 20 – 1948 Q2

TimeGhost History

Published 13 Apr 2025In 1948, the British departure from Palestine plunges the region into chaos. Amid bombings, massacres, and forced displacements, a brutal civil war escalates into the Arab-Israeli conflict, reshaping the Middle East forever. As Israel declares independence, Arab armies invade, and atrocities on both sides deepen hatred and tragedy. Can either side emerge victorious, or has the cycle of violence become unstoppable?

(more…)

April 6, 2025

The Last Pagan Temple in Egypt

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 6 Dec 2024The Temple of Isis at Philae, on Egypt’s southern edge, survived until the reign of Justinian, long after every other temple had been shut down.

March 25, 2025

QotD: The nature of kingship

As I hammer home to my students, no one rules alone and no ruler can hold a kingdom by force of arms alone. Kings and emperors need what Hannah Arendt terms power – the ability to coordinate voluntary collective action – because they cannot coerce everyone all at once. Indeed, modern states have far, far more coercive power than pre-modern rulers had – standing police forces, modern surveillance systems, powerful administrative states – and of course even then rulers must cultivate power if only to organize the people who run those systems of coercion.

How does one cultivate power? The key factor is legitimacy. To the degree that people regard someone (or some institution) as the legitimate authority, the legitimate ruler, they will follow their orders mostly just for the asking. After all, if a firefighter were to run into the room you are in right now and say “everybody out!” chance are you would not ask a lot of questions – you would leave the room and quickly! You’re assuming that they have expertise you don’t, a responsibility to fight fires, may know something you don’t and most importantly that their position of authority as the Person That Makes Sure Everything Doesn’t Burn Down is valid. So you comply and everyone else complies as a group which is, again, the voluntary coordination of collective action (the firefighter is not going to beat all of you if you refuse so this isn’t violence or force), which is power.

At the same time, getting that compliance, for the firefighter, is going to be dependent on looking the part. A firefighter who is a fit-looking person in full firefighting gear who you’ve all seen regularly at the fire station is going to have an easier time getting you all to follow directions than a not-particularly-fit fellow who claims to be a firefighter but isn’t in uniform and you aren’t quite sure who they are or why they’d be qualified. The trappings contribute to legitimacy which build power. Likewise, if your local firefighters are all out of shape and haven’t bothered to keep their fire truck in decent shape, you – as a community – might decide they’ve lost your trust (they’ve lost legitimacy, in fact) and so you might replace them with someone else who you think could do the job better.

Royal power works in similar ways. Kings aren’t obeyed for the heck of it, but because they are viewed as legitimate and acting within that legitimate authority (which typically means they act as the chief judge, chief general and chief priest of a society; those are the three standard roles of kingship which tend to appear, in some form, in nearly all societies with the institution). The situation for monarchs is actually more acute than for other forms of government. Democracies and tribal councils and other forms of consensual governments have vast pools of inherent legitimacy that derives from their government form – of course that can be squandered, but they start ahead on the legitimacy game. Monarchs, by contrast, have to work a lot harder to establish their legitimacy and doing so is a fairly central occupation of most monarchies, whatever their form. That means to be rule effectively and (perhaps more importantly) stay king, rulers need to look the part, to appear to be good monarchs, by whatever standard of “good monarch” the society has.

In most societies that has traditionally meant that they need not only to carry out those core functions (chief general, chief judge, chief priest), but they need to do so in public in a way that can be observed by their most important supporters. In the case of a vassalage-based political order, that’s going to be key vassals (some of whom may be mayors or clerics rather than fellow military aristocrats). We’ve talked about how this expresses itself in the “chief general” role already.

I’m reminded of a passage from the Kadesh Inscription, an Egyptian inscription from around 1270 BC which I often use with students; it recounts (in a self-glorifying and propagandistic manner) the Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC). The inscription is, of course, a piece of royal legitimacy building itself, designed to convince the reader that the Pharaoh did the “chief general” job well (he did not, in the event, but the inscription says he did). What is relevant here is that at one point he calls his troops to him by reminding them of the good job he did in peace time as a judge and civil administrator (the “chief judge” role) (trans. from M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol 2 (1976)):

Did I not rise as lord when you were lowly,

and made you into chiefs [read: nobles, elites] by my will every day?

I have placed a son on his father’s portion,

I have banished all evil from the land.

I released your servants to you,

Gave you things that were taken from you.

Whosoever made a petition,

“I will do it,” said I to him daily.

No lord has done for his soldiers

What my majesty did for your sakes.Bret Devereaux, “Miscellanea: Thoughts on CKIII: Royal Court”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-02-18.

February 23, 2025

QotD: The Hellenistic army system as a whole

I should note here at the outset that we’re not going to be quite done with the system here – when we start looking at the third and second century battle record, we’re going to come back to the system to look at some innovations we see in that period (particularly the deployment of an enallax or “articulated” phalanx). But we should see the normal function of the components first.

No battle is a perfect “model” battle, but the Battle of Raphia (217BC) is handy for this because we have the two most powerful Hellenistic states (the Ptolemies and Seleucids) both bringing their A-game with very large field armies and deploying in a fairly standard pattern. That said, there are some quirks to note immediately: Raphia is our only really good order of battle of the Ptolemies, but as our sources note there is an oddity here, specifically the mass deployment of Egyptians in the phalanx. As I noted last time, there had always been some ethnic Egyptians (legal “Persians”) in the phalanx, but the scale here is new. In addition, as we’ll see, the position of Ptolemy IV himself is odd, on the left wing matched directly against Antiochus III, rather than on his own right wing as would have been normal. But this is mostly a fairly normal setup and Polybius gives us a passably good description (better for Ptolemy than Antiochus, much like the battle itself).

We can start with the Seleucid Army and the tactical intent of the layout is immediately understandable. Antiochus III is modestly outnumbered – he is, after all, operating far from home at the southern end of the Levant (Raphia is modern-day Rafah at the southern end of Gaza), and so is more limited in the force he can bring. His best bet is to make his cavalry and elephant superiority count and that means a victory on one of the wings – the right wing being the standard choice. So Antiochus stacks up a 4,000 heavy cavalry hammer on his flank behind 60 elephants – Polybius doesn’t break down which cavalry, but we can assume that the 2,000 with Antiochus on the extreme right flank are probably the cavalry agema and the Companions, deployed around the king, supported by another 2,000 probably Macedonian heavy cavalry. He then uses his Greek mercenary infantry (probably thureophoroi or perhaps some are thorakitai) to connect that force to the phalanx, supported by his best light skirmish infantry: Cretans and a mix of tough hill folks from Cilicia and Caramania (S. Central Iran) and the Dahae (a steppe people from around the Caspian Sea).

His left wing, in turn, seems to be much lighter and mostly Iranian in character apart from the large detachment of Arab auxiliaries, with 2,000 more cavalry (perhaps lighter Persian-style cavalry?) holding the flank. This is a clearly weaker force, intended to stall on its wing while Antiochus wins to the battle on the right. And of course in the middle [is] the Seleucid phalanx, which was quite capable, but here is badly outnumbered both because of how full-out Ptolemy IV has gone in recruiting for his “Macedonian” phalanx and also because of the massive infusion of Egyptians.

But note the theory of victory Antiochus III has: he is going to initiate the battle on his right, while not advancing his left at all (so as to give them an easier time stalling), and hope to win decisively on the right before his left comes under strain. This is, at most, a modest alteration of Alexander-Battle.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy IV seems to have anticipated exactly this plan and is trying to counter it. He’s stacked his left rather than his right with his best troops, including his elite infantry (the agema and peltasts, who, while lighter, are more elite) and his best cavalry, supported by his best (and only) light infantry, the Cretans.1 Interestingly, Polybius notes that Echecrates, Ptolemy’s right-wing commander waits to see the outcome of the fight on the far side of the army (Polyb. 6.85.1) which I find odd and suggests to me Ptolemy still carried some hope of actually winning on the left (which was not to be). In any case, Echecrates, realizing that sure isn’t happening, assaults the Seleucid left.

I think the theory of victory for Ptolemy is somewhat unconventional: hold back Antiochus’ decisive initial cavalry attack and then win by dint of having more and heavier infantry. Indeed, once things on the Ptolemaic right wing go bad, Ptolemy moves to the center and pushes his phalanx forward to salvage the battle, and doing that in the chaos of battle suggests to me he always thought that the matter might be decided that way.

In the event, for those unfamiliar with the battle: Antiochus III’s right wing crumples the Ptolemaic left wing, but then begins pursuing them off of the battlefield (a mistake he will repeat at Magnesia in 190). On the other side, the Gauls and Thracians occupy the front face of the Seleucid force while the Greek and Mercenary cavalry get around the side of the Seleucid cavalry there and then the Seleucid left begins rolling up, with the Greek mercenary infantry hitting the Arab and Persian formations and beating them back. Finally, Ptolemy, having escaped the catastrophe on his left wing, shows up in the center and drives his phalanx forward, where it wins for what seem like obvious reasons against an isolated Seleucid phalanx it outnumbers almost 2-to-1.

But there are a few structural features I want to note here. First, flanking this army is really hard. On the one hand, these armies are massive and so simply getting around the side of them is going to be difficult (if they’re not anchored on rivers, mountains or other barriers, as they often are). Unlike a Total War game, the edge of the army isn’t a short 15-second gallop from the center, but likely to be something like a mile (or more!) away. Moreover, you have a lot of troops covering the flanks of the main phalanx. That results, in this case, in a situation where despite both wings having decisive actions, the two phalanxes seem to be largely intact when they finally meet (note that it isn’t necessarily that they’re slow; they seem to have been kept on “stand by” until Ptolemy shows up in the center and orders a charge). If your plan is to flank this army, you need to pick a flank and stack a ton of extra combat power there, and then find a way to hold the center long enough for it to matter.

Second, this army is actually quite resistive to Alexander-Battle: if you tried to run the Issus or Gaugamela playbook on one of these armies, you’d probably lose. Sure, placing Alexander’s Companion Cavalry between the Ptolemaic thureophoroi and Gallic mercenaries (about where he’d normally go) would have him slam into the Persian and Medean light infantry and probably break through. But that would be happening at the same time as Antiochus’ massive 4,000-horse, 60-elephant hammer demolished Ptolemaic-Alexander’s left flank and moments before the 2,000 cavalry left-wing struck Alexander himself in his flank as he advanced. The Ptolemaic army is actually an even worse problem, because its infantry wings are heavier, making that key initial cavalry breakthrough harder to achieve. Those chunky heavy-cavalry wings ensure that an effort to break through at the juncture of the center and the wing is foolhardy precisely because it leaves the breakthrough force with heavy cavalry to one side and heavy infantry to the other.

I know this is going to cause howls of pain and confusion, but I do not think Alexander could have reliably beaten either army deployed at Raphia; with a bit of luck, perhaps, but on the regular? No. Not only because he’d be badly outnumbered (Alexander’s army at Gaugamela is only 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry) but because these armies were adapted to precisely the sort of army he’d have and the tactics he’d use. Even without the elephants (and elephants gave Alexander a hell of a time at the Hydaspes), these armies can match Alexander’s heavy infantry core punch-for-punch while having enough force to smash at least one of his flanks, probably quite quickly. Note that the Seleucid Army – the smaller one at Raphia – has almost exactly as much heavy infantry at Raphia as Alexander at Gaugamela (30,000 to 31,000), and close to as much cavalry (6,000 to 7,000), but of course also has a hundred and two elephants, another 5,000 more “medium” infantry and massive superiority in light infantry (27,000 to 9,000). Darius III may have had no good answer to the Macedonian phalanx, but Antiochus III has a Macedonian phalanx and then essentially an entire second Persian-style army besides (and his army at Magnesia is actually more powerful than his army at Raphia).

This is not a degraded form of Alexander’s army, but a pretty fearsome creature of its own, which supplements an Alexander-style core with larger amounts of light and medium troops (and elephants), without sacrificing much, if any, in terms of heavy infantry and cavalry. The tactics are modest adjustments to Alexander-Battle which adapt the military system for symmetrical engagements against peer armies. The Hellenistic Army is a hard nut to crack, which is why the kingdoms that used them were so successful during the third century, to the point that, until the Romans show up, just about the only thing which could beat a Hellenistic army was another Hellenistic army.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part Ib: Subjects of the Successors”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-01-26.

1. You can tell how much those Cretans are valued, given that they get placed in key positions in both armies.

January 11, 2025

QotD: “Composite” pre-gunpowder infantry units

I should be clear I am making this term up (at least as far as I know) to make a contrast between what Total War has, which are single units made up of soldiers with identical equipment loadouts that have a dual function (hybrid infantry) and what it doesn’t have: units composed of two or more different kinds of infantry working in concert as part of a single unit, which I am going to call composite infantry.

This is actually a very old concept. The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-609 BC) is one of the earliest states where we have pretty good evidence for how their infantry functioned – there was of course infantry earlier than this, but Bronze Age royal records from Egypt, Mesopotamia or Anatolia tend to focus on the role of elites who, by the late Bronze Age, are increasingly on chariots. But for the early Iron Age Neo-Assyrian empire, the fearsome effectiveness of its regular (probably professional) infantry, especially in sieges, was a key component of its foreign-policy-by-intimidation strategy, so we see a lot more of them.

That infantry was split between archers and spear-and-shield troops, called alternately spearmen (nas asmare) or shield-bearers (sab ariti). In Assyrian artwork, they are almost always shown in matched pairs, each spearman paired off with a single archer, physically shielding the archer from attack while the archer shoots. The spearmen are shown with one-handed thrusting spears (of a fairly typical design: iron blade, around 7 feet long) and a shield, either a smaller round shield or a larger “tower” shield. Assyrian records, meanwhile, reinforce the sense that these troops were paired off, since the number of archers and spearmen typically match perfectly (although the spearmen might have subtypes, particularly the “Qurreans” who may have been a specialist type of spearman recruited from a particular ethnic group; where the Qurreans show up, if you add Qurrean spearmen to Assyrian spearmen, you get the number of archers). From the artwork, these troops seem to have generally worked together, probably lined up in lines (in some cases perhaps several pairs deep).

The tactical value of this kind of composite formation is obvious: the archers can develop fire, while the spearmen provide moving cover (in the form of their shields) and protection against sudden enemy attack by chariot or cavalry with their spears. The formation could also engage in shock combat when necessary; the archers were at least sometimes armored and carried swords for use in close combat and of course could benefit (at least initially) from the shields of the front rank of spearmen.

The result was self-shielding shock-capable foot archer formations. Total War: Warhammer also flirts with this idea with foot archers who have their own shields, but often simply adopts the nonsense solution of having those archers carry their shields on their backs and still gain the benefit of their protection when firing, which is not how shields work (somewhat better are the handful of units that use their shields as a firing rest for crossbows, akin to a medieval pavisse).

We see a more complex version of this kind of composite infantry organization in the armies of the Warring States (476-221 BC) and Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) periods in China. Chinese infantry in this period used a mix of weapons, chiefly swords (used with shields), crossbows and a polearm, the ji which had both a long spearpoint but also a hook and a striking blade. In Total War: Three Kingdoms, which represents the late Han military, these troop-types are represented in distinct units: you have a regiment of ji-polearm armed troops, or a regiment of sword-and-shield troops, or a regiment of crossbowmen, which maneuver separately. So you can have a block of polearms or a block of crossbowmen, but you cannot have a mixed formation of both.

Except that there is a significant amount of evidence suggesting that this is exactly how the armies of the Han Dynasty used these troops! What seems to have been common is that infantry were organized into five-man squads with different weapon-types, which would shift their position based on the enemy’s proximity. So against a cavalry or chariot charge, the ji might take the front rank with heavier crossbows in support, while the sword-armed infantry moved to the back (getting them out of the way of the crossbows while still providing mass to the formation). Of course against infantry or arrow attack, the swordsmen might be moved forward, or the crossbowmen or so on (sometimes there were also spearmen or archers in these squads as well). These squads could then be lined up next to each other to make a larger infantry formation, presenting a solid line to the enemy.

(For more on both of these military systems – as well as more specialist bibliography on them – see Lee, Waging War (2016), 89-99, 137-141.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

December 20, 2024

The Murder of Egypt’s Forgotten Queen – Shajar al-Durr & Om Ali

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Aug 13, 2024The national dessert of Egypt: bread pudding made from crisp flatbread, pistachios, almonds, sultanas, spices, and rose water

City/Region: Egypt | Baghdad

Time Period: 10th-13th CenturiesOm Ali is the national dessert of Egypt, and its roots go back at least to the 10th century, when we get the base recipe for my version. I took inspiration from other medieval recipes and added the nuts, sultanas, and spices, though they would also use ingredients like camphor, chicken, poppyseeds, and musk.

I really like the flavors, and the dish is sweet without being too sweet, but the bread gives it a kind of noodle-like texture which is a bit odd. Modern versions often use dry croissants, so I won’t judge if you use them or something like phyllo or puff pastry in place of the homemade roqaq.

Take semolina or white bread and soak it in milk until saturated. Then, take half a pound of sugar, or as much as is needed for the amount of bread, crush it, and mix it with the bread. Then, take a clean and shallow pot … add the soaked bread, milk, and sugar … Return the pot to slow burning coals. When the filling is cooked and set, remove the pot from the fire, turn it out onto a wide bowl and serve, God willing.

— Kitab al-Tabikh by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, 10th Century

December 4, 2024

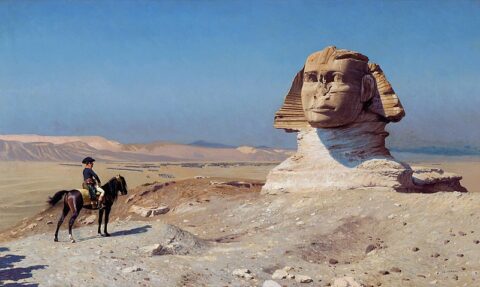

Facing the Sphinx

Andrew Doyle provides a bit of historical context for the question currently convulsing Britain’s supreme court:

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, 1886, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904).

Painting from the Hearst Castle collection (Accession number 529-9-5092) via Wikimedia Commons.

It was known as the sphinx: a terrifying hybrid with a lion’s body and a human head. According to the legend, the sphinx was sent to guard the city of Thebes by the goddess Hera who wanted to punish the citizens for some ancient crime. It perched on a nearby mountain, and whenever anyone attempted to enter or leave the city it would pose a riddle. If the traveller failed to answer, he or she would be devoured, but the riddle was so confounding, so esoteric, so abstruse, that even the greatest intellectuals of the day soon found themselves reduced to snacks for the mighty sphinx.

And what was this riddle? What was the question that foxed even the sharpest of minds? It was simply: “what is a woman?”

And now, a hearing at the UK’s supreme court has taken place to solve the sphinx’s riddle once and for all. The campaign group For Women Scotland raised the case in order to challenge the Scottish government’s contention that the word “sex” in the Equality Act includes men who identify as female and hold a Gender Recognition Certificate. We can expect the results of this hearing over the next few months.

And yet I’m sure most of you are thinking to yourselves: “How will these judges possibly answer such a metaphysical conundrum?” And you’re not alone. Many valiant and learned individuals have fallen in the attempt.

[…]

Inevitably, activists tend to frame the entire question of “what is a woman?” as some kind of “gotcha”. Or they claim that to even broach the question of sex differences is “transphobic” and “hateful”, a means to bully the most marginalised. But of course, the transgender lobby wields incredible power in our society; it can see people silenced, harassed and even arrested for speaking truth, and all in the name of “progress”. Genuinely marginalised groups do not enjoy this kind of clout.

Others will say that all of this is a distraction from the “real issues”. But gender identity ideology has a deleterious impact on everyone, and has proved to be a major factor in political change. In its post-election analysis in November 2024, entitled “How Trump won, and how Harris lost”, the New York Times singled out an advertising campaign by Trump’s team which drew attention to Kamala Harris’s statement that all prison inmates identifying as transgender ought to have access to surgery. The tagline was: “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you”.

Although the New York Times considered this a “seemingly obscure topic”, its writers were forced to admit its efficacy. Even Trump’s aides had been astonished at how popular the campaign had proven. According to the political action committee Future Forward, a group established to support the Democratic Party, this advertisement actuated a 2.7 point shift in favour of Trump among those who saw it. Inevitably, the New York Times misclassified the message as “anti-trans”, a ploy guaranteed to exacerbate the very resentment that made the campaign so effective in the first place.

To ask a politician the question “what is a woman?” isn’t some kind of cruel test. It’s a way to ensure that those in power are being honest with us. We know that they know the answer. And they know that we know that they know the answer. It isn’t that they can’t define it, it’s that they are too frightened to do so. It’s one thing for politicians to lie and hope they get away with it, but quite another for them to lie when they know that we are all fully aware that they are lying. It suggests a degree of contempt for the electorate that is unlikely to translate to success at the ballot box. And it hasn’t escaped the attention of feminists that the question “what is a man?” mysteriously never seems to be asked.

November 29, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 8 – The Hellenistic Age

seangabb

Published Jul 17, 2024This eighth lecture in the course covers the Hellenistic Age of Greece — from the death of Alexander in 323 BC to about the death of Cleopatra in 30 BC.

(more…)

November 27, 2024

The Deadly Job of Royal Food Taster

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jul 23, 2024Sautéed mushrooms in a honey, long pepper, and garum glaze

City/Region: Rome

Time Period: 1st CenturyFood tasters checking for poison aren’t around so much anymore, but it was an important job for thousands of years. But what happens when the food taster is the one adding in the poison?

Emperor Claudius found this out the hard way when he supposedly ate some of his favorite mushrooms, and then became the victim of a double-poisoning by his taster and his physician.

We can’t know for sure what Emperor Claudius’s favorite mushroom dish was, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it was this. I don’t care for the texture of mushrooms, but the flavor is excellent. The sweetness from the honey, spiciness from the long pepper, and the earthiness of the mushrooms combine for a complex dish that is delicious.

Another Method for Mushrooms

Place the chopped stalks in a clean pan, adding pepper, lovage, and a little honey. Mix with garum. Add a little oil.

— Apicius de re coquinaria, 1st century

QotD: The Great Library and its competitors

One of the odder elements of the New Atheist myths about the Great Library is the strange idea that its (supposed) destruction somehow singlehandedly wiped out the (alleged) advanced scientific knowledge of the ancient world in one terrible cataclysm. It doesn’t take much thought, however, to realise this makes absolutely no sense. The idea that there was just one library in the whole of the ancient world is clearly absurd and, as the mentions of other rival libraries above have already made clear, there were of course hundreds of libraries, great and small, across the ancient world. Libraries and the communities of scholars and scribes that serviced them were established by rulers and civic worthies as the kind of prestige project that was seen as part of their role in ancient society and marked their city or territory as cultured and civilised.

The Ptolemies were not the only successors to Alexander who built a Mouseion with a library; their Seleucid rivals in Syria also built one in Antioch in the reigns of Antiochus IX Eusebes (114-95 BC) or Antiochus X Philopater (95-92 BC). Roman aristocrats and rulers also included the establishment of substantial libraries as part of their civic service. Julius Caesar had intended to establish a library next to the Forum in Rome but this was ultimately achieved after his death by Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 BC – 4 AD), a soldier, politician and scholar who retired to a life of study after the tumults of the Civil Wars. Augustus established the Palatine Library in the Temple of Apollo and founded another one in the Portus Octaviae, next to the Theatre of Marcellus at the southern end of the Field of Mars. Vespasian established one in the Temple of Peace in 70 AD, but probably the largest of the Roman libraries was that of Trajan in his new forum beside the famous column that celebrates his Dacian wars. As mentioned above, this large building probably contained around 20,000 scrolls and had two main chambers – one for Greek and the other for Latin authors. Trajan’s library also seems to have established a design and layout that would be the model for libraries for centuries: a hall with desks and tables for readers with books in niches or shelves around the walls and on a mezzanine level. Libraries also came to be established in Roman bath complexes, with a very large one at the Baths of Caracalla and another at the Baths of Diocletian.

Several of these libraries were substantial. The Library of Celsus at Ephesus was built in c. 117 AD by the son of Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus in honour of his father, who had been a senator and consul in Rome, and its reconstructed facade is one of the major archaeological features of the site today. It was said to be the third largest library in the ancient world, surpassed only by the great libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria. The Great Library of Pergamon was established by the Attalid rulers of that city state and it was the true rival of the library of the Alexandrian Mouseion. It is said that the Ptolemies were so threatened by its size and the reputation of its scholars that they banned the export of papyrus to Pergamon, causing the Attalids to commission the invention of parchment as a substitute, though this is most likely a legend. What is absolutely clear, however, is that the idea that the Great Library of Alexandria was unique, whether in nature or even in size, is nonsense.

The weird idea that the loss of the Great Library was some kind of singular disaster is at least partially due to the fact that none of the various other great libraries of the ancient world are known to casual readers, so it may be easy for them to assume it was somehow unique. It also seems to stem, again, from the emphasis in popular sources on the mythical immense size of its collection which, as discussed above, is based on a naive acceptance of varied and wildly exaggerated sources. Finally, it seems to stem in no small part from (yet again) Sagan’s influential but fanciful picture of the institution as a distinctively secular hub of scientific research and, by implication, technological innovation.

Tim O’Neill, “The Great Myths 5: The Destruction Of The Great Library Of Alexandria”, History for Atheists, 2017-07-02.

September 26, 2024

Why Three Arab Nations Lost the Six-Day War Against Israel

Real Time History

Published Jun 5, 2024In just six days in 1967 Israel managed to decisively defeat Egypt, Jordan and Syria in the Six Day War. In the process they expand the territory they control with the Golan Heights, Sinai, the West Bank, and Gaza.

(more…)

September 8, 2024

Ancient sources

In writing history from the early modern period onward, it’s a common problem to have too many sources for a given event so that it’s the job of the historian to (carefully, one hopes) select the ones that hew closer to the objective truth. In ancient history, on the other hand, we have so few sources to rely upon that it’s a luxury to have multiple accounts of a given event from which to choose:

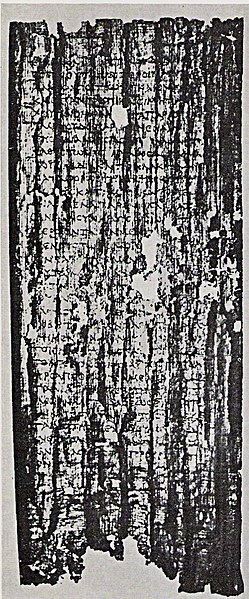

Unrolled papyrus scroll recovered from the Villa of the Papyri.

Picture published in a pamphlet called “Herculaneum and the Villa of the Papyri” by Amedeo Maiuri in 1974. (Wikimedia Commons)

We used to play this game in graduate school: find one, lose one. Find one referred to finding a lost ancient text, something that we know existed at one time because other ancient sources talk about it, but which has been lost to the ages. What if someone was digging somewhere in Egypt and found an ancient Greco-Roman trash dump with a complete copy of a precious text – which one would we wish into survival? Lose one referred to some ancient text we have, but we would give up in some Faustian bargain to resurrect the former text from the dead. Of course there is a bit of the butterfly effect; that’s what made it fun. As budding classicists, we grew up in an academic world where we didn’t have A, but did have B. How different would classical scholarship be if that switched? If we had had A all along, but never had B? For me, the text I always chose to find was a little-known pamphlet circulated in the late fourth century by a deposed Spartan king named Pausanias. It’s one of the few texts about Sparta written by a Spartan while Sparta was still hegemonic. I always lost the Gospel of Matthew. It’s basically a copy of Mark, right down to the grammar and syntax. Do we really need two?

What would you choose? Consider that Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are only two of the poems that make up the eight-part Epic Cycle. Or that Aristotle wrote a lost treatise on comedy, not to mention his own Socratic dialogues that Cicero described as a “river of gold”. Or that only eight of Aeschylus’s estimated 70 plays survive. Even the Hebrew Old Testament refers to 20 ancient texts that no longer exist. There are literally lost texts that, if we had them, would in all likelihood have made it into the biblical canon.

The problem is more complex than the fact that many texts were lost to the annals of history. Most people just see the most recent translation of the Iliad or works of Cicero on the shelf at a bookstore, and assume that these texts have been handed down in a fairly predictable way generation after generation: scribes faithfully made copies from ancient Greece through the Middle Ages and eventually, with the advent of the printing press, reliable versions of these texts were made available in the vernacular of the time and place to everyone who wanted them. Onward and upward goes the intellectual arc of history! That’s what I thought, too.

But the fact is, many of even the most famous works we have from antiquity have a long and complicated history. Almost no text is decoded easily; the process of bringing readable translations of ancient texts into the hands of modern readers requires the cooperation of scholars across numerous disciplines. This means hours of hard work by those who find the texts, those who preserve the texts, and those who translate them, to name a few. Even with this commitment, many texts were lost – the usual estimate is 99 percent – so we have no copies of most of the works from antiquity.1 Despite this sobering statistic, every once in a while, something new is discovered. That promise, that some prominent text from the ancient world might be just under the next sand dune, is what has preserved scholars’ passion to keep searching in the hope of finding new sources that solve mysteries of the past.

And scholars’ suffering paid off! Consider the Villa of the Papyri, where in the eighteenth century hundreds, if not thousands, of scrolls were discovered carbonized in the wreckage of the Mount Vesuvius eruption (79 AD), in a town called Herculaneum near Pompeii. For over a century, scholars have hoped that future science might help them read these scrolls. Just in the last few months – through advances in computer imaging and digital unwrapping – we have read the first lines. This was due, in large part, to the hard work of Dr. Brent Seales, the support of the Vesuvius Challenge, and scholars who answered the call. We are now poised to read thousands of new ancient texts over the coming years.

[…]

Now let’s look at a text with a very different history, the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia. The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia is the name given to a group of papyrus fragments found in 1906 at the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus, modern Al-Bahnasa, Egypt (about a third of the way down the Nile from Cairo to the Aswan Dam). These fragments were found in an ancient trash heap. They cover Greek political and military history from the closing years of the Peloponnesian War into the middle of the fourth century BC. In his Hellenica, Xenophon covers the exact same time frame and many of the same events.2 Both accounts pick up where Thucydides, the leading historian of the Peloponnesian War (fought between Athens and Sparta in the fifth century BC), leaves off.

While no author has been identified for the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, the grammar and style date the text to the era of the events it describes. This is a recovered text, meaning it was completely lost to history and only discovered in the early twentieth century. Here, the word discovered is appropriately used, as this was not a text that was renowned in ancient times. No ancient historians reference it, and it did not seem to have a lasting impact in its day. What is dismissible in the past is forgotten in the present. The text is written in Attic Greek. This implies that whoever wrote the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia must have been an elite familiar enough with the popular Attic style to replicate it, and likely intended for the history to equal those of Thucydides and Xenophon. There were other styles available to use at the time but Attic Greek was the style of both the aforementioned historians, as well as the writing style of the elite originating in Athens. Any history not written in Attic would have been seen as inferior. Given that the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was lost for thousands of years, it would seem our author failed in his endeavor to mirror the great historians of classical Greece.

The Hellenica Oxyrhynchia serves as a reminder that the modern discovery of ancient texts continues. Many times, these are additional copies of texts we already have. This is not to say these copies are not important. Such was the case of the aforementioned Codex Siniaticus, discovered by biblical scholar Konstantin von Tischendorf in a trash basket, waiting to be burned, in a monastery near Mount Sinai in Egypt in 1844. Upon closer examination, Tischendorf discovered this “trash” was in fact a nearly complete copy of the Christian Bible, containing the earliest complete New Testament we have. One major discrepancy is that the famous story of Jesus and the woman taken in adultery – from which the oft-quoted passage “let he who is without sin cast the first stone” originates – is not found in the Codex Sinaiticus.

Yet, sometimes something truly new to us, that no one has seen for thousands of years, is unearthed. In the case of the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia, no one seemingly had looked at this text for at least 1,500 years, maybe more. This demonstrates that there is always the possibility that buried in some ancient scrap heap in the desert might be a completely new text that, once published for wider scholarship, greatly increases our knowledge of the ancients.

How does this specific text increase our knowledge? Bear in mind that before this period of Greek history, we have just one historian per era. Herodotus is the only source we have for the Greco-Persian Wars (480–479), and the aforementioned Thucydides picks up from there and quickly covers the political climate before beginning his history proper with the advent of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. But Thucydides’s history is unfinished – one ancient biography claims he was murdered on his way back to Athens around 404 BC. Many doubt this, citing evidence that he lived into the early fourth century BC. Either way, his narrative ends abruptly. Xenophon picks it up from there, and later we get a more brief history of this period from Diodorus, who wrote much later, between 60 and 30 BC. While describing the same time frame and many of the same events, these two sources vary widely in their descriptions of certain events. In some cases, they make mutually exclusive claims. One historian must have got it wrong.

For centuries, Xenophon’s account was the preferred text. That is not to say Diodorus’s history was dismissed, but when the two accounts were in conflict, Xenophon’s testimony got the nod. This was partially because Xenophon actually lived during the times he wrote about, whereas Diodorus lived 200 years after these events in Greek history. Consider if there were two conflicting accounts of the Battle of Gettysburg from two different historians: one actually lived during and participated in the war, while the other was a twenty-first century scholar living 150 years after the events he describes. They disagree on key elements of the battle. Who do you believe? This was precisely the case with Xenophon and Diodorus. Yet, once the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia was published, it corroborated Diodorus’s history far more than that of Xenophon, forcing historians to reconsider their bias toward the older of the two accounts.

1. You can find a list of texts we know that we have lost at the Wikipedia page “Lost literary work“.

2. “Oxyrhynchus Historian”, in The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, ed. MC Howatson (Oxford University Press, 2011).

June 24, 2024

History Summarized: Augustus Versus Antony

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Apr 6, 2018Now that Caesar’s assassins are out of the picture, which would-be dictator will defeat the other to become the sole-ruler of Rome? In today’s episode of “How Long Before There’s Another Civil War?”: Not a lot … honestly not a very long time … BUT THEN WE GET THE ROMAN EMPIRE WOOOOOOOOO~~~

May 4, 2024

Shakespeare Summarized: Antony and Cleopatra

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published Dec 2, 2016Hey, remember almost exactly three years ago when I summarized Julius Caesar? Published on December 1st, even? A coincidence I totally planned when I spontaneously decided to do this video today?