The importance of the Carolingian Renaissance for text-preservation, by the by, is immediately relevant to anyone who has looked at almost any manuscript tradition: the absolute crushing ubiquity of Caroline minuscule, the standard writing form of the period, is just impossible to ignore (also, I love the heck out of Caroline minuscule because it is easy to both read and write – which is why it was so popular in this period; an unadorned, practical script – I love it; it’s the only medieval script I can write in with any meager proficiency). The sudden burst of book-copying tends to mean – for ancient works, at least, that if they survived to c. 830, then they probably survive to the present. Sponsored by Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, the scribes of the Carolingian period (mostly monks) rescued much of the Latin classical corpus we now have from oblivion. It is depressingly common to hear “hot-takes” or pop-culture references to how the “medievals” or the Church were supposedly responsible for destroying literature or ancient knowledge (this trope runs wild in Netflix’s recent Castlevania series, for instance) – the reverse is true. Without those 9th century monks, we’d probably have about as much Latin literature as we have Akkadian literature: not nothing, but far, far less. Say what you will about the medieval Church, you cannot blame the loss of the Greek or Roman tradition on them.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: A Trip Through Dhuoda of Uzès (Carolingian Values)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-27.

October 11, 2022

QotD: The debt we owe to the Carolingian Renaissance

August 20, 2022

The historical tourist attractions of Pisa

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes talks about a recent trip to Italy, specifically the historically interesting places in Pisa and Lucca:

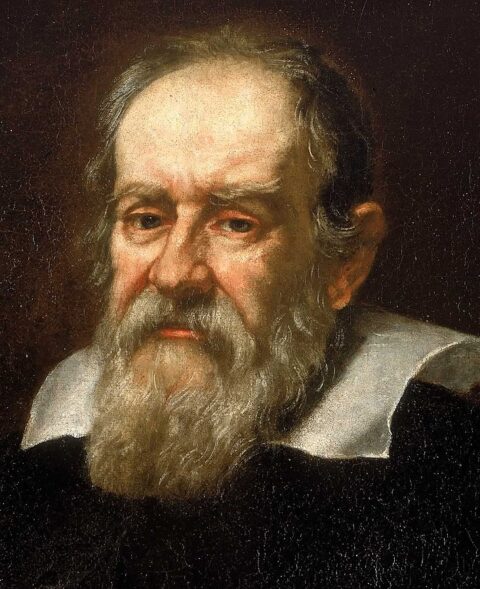

Galileo Galilei circa 1640.

Detail of an oil portrait by Justus Sustermans (1597-1681) from the National Maritime Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

Some are famous. Galileo Galilei, for example, is said to have used the leaning tower of Pisa to drop two spheres of different masses, to show that they would fall at the same speed — at least, that’s what his disciple Vincenzo Viviani claimed, ten years after Galileo’s death, and many decades after the alleged demonstration. Even if Viviani was being accurate, however, Galileo certainly wasn’t the first to demonstrate the concept. And Viviani mistakenly claimed priority for all sort of other scientific breakthroughs for his master, so like most other historians I’m inclined to doubt the story.

Nonetheless, Pisa was certainly Galileo’s birthplace — though it turns out that there are three different locations in the city to have claimed the honour over the years.

Galileo was initially thought to have been born in or near the fortress (its walls are impressive to look at and contain a pleasant garden). But this location was then refuted on the basis that for Galileo’s father Vincenzo Galilei to have lived in the fortress he would have had to have been a master at arms, which he was not. He was in fact a merchant and lute-maker. So in the nineteenth century a new location emerged: the casa Bocca, on the Stretto Borgo, which Vincenzo rented a few months before Galileo’s birth, and where the Galilei family lived for the next decade. It seemed a secure candidate for a while, except for a weird discrepancy: Galileo’s baptismal certificate assigned his birth to the wrong parish.

It then emerged that Galileo’s mother’s family — the Ammannati — lived in the correct parish, and that the custom of the time was for women to return to their parents’ home for the birth of their first child. Thus, the evidence points to Galileo having been born at the Casa Ammanati on the via Giusti. It’s a neat story of how a tourist destination can jump around based on new research, though there’s unfortunately not much to visit there other than a plaque.

In terms of things to actually see, one of the most impressive things in Pisa is the Museo delle Navi Antiche (Museum of Ancient Ships), which we found to be undeservedly deserted. Housed in the old stables for the city’s cavalry, and once the site of the Medici-era naval arsenal, the museum gives a fantastically thorough overview of the city from its Etruscan beginnings through to Roman subjugation, Ostrogothic invasion, Byzantine reconquest, and Longbeard settlement in the sixth century (although they’re usually called the Lombards, this comes from langobardi — literally, longbeards — so I think calling them that is both more accurate and more fun).

The museum’s highlight, however, is the ancient ships for which it is named, and which are incredibly well-preserved. I was stunned to see a massive actual wooden anchor, not just a reconstruction, of a cargo ship from the second century BC. It’s so well-preserved that you can even make out a decoration, carved into the wood, of a ray fish. The same goes for the rest of the various ships’ timbers. You can see almost all of their original hulls and planking, as well as finer details like rudder-oars, benches for the rowers, and in one case even the ship’s name carved into the wood — the Alkedo, which appears to have been a pleasure boat from the first century. Apparently, during excavation, the archaeologists could even make out the Alkedo‘s original red and white paint, as well as the impression left by an iron sheet that had covered its prow. The ships’ contents are often just as astonishing, with well-preserved baskets, fragments of clothing, and even bits of the rigging like its wooden pulleys and ropes. Well worth a visit.

August 15, 2022

QotD: Sparta – the North Korea of the Classical era

When we started this series, we had two myths, the myth of Spartan equality and the myth of Spartan military excellence. These two myths dominate the image of Sparta in the popular consciousness, permeating game, film and written representations and discussions of Sparta. These myths, more than any real society, is what companies like Spartan Race, games like Halo, and – yes – films like 300 are tapping into.

But Sparta was not equal, in fact it was the least equal Greek polis we know of. It was one of the least equal societies in the ancient Mediterranean, and one which treated its underclasses – who made up to within a rounding error of the entire society by the end – terribly. You will occasionally see pat replies that Sparta was no more dependent on slave labor than the rest of Greece, but even a basic demographic look makes it clear this is not true. Moreover our sources are clear that the helots were the worst treated slaves in Greece. Even among the Spartiates, Sparta was not equal and it never was.

And Sparta was not militarily excellent. Its military was profoundly mediocre, depressingly average. Even in battle, the one thing they were supposed to be good at, Sparta lost as much as it won. Judging Sparta as we should – by how well it achieved strategic objects – Sparta’s armies are a comprehensive failure. The Spartan was no super-soldier and Spartan training was not excellent. Indeed, far from making him a super-soldier, the agoge made the Spartans inflexible, arrogant and uncreative, and those flaws led directly to Sparta’s decline in power.

And I want to stress this one last time, because I know there are so many people who would pardon all of Sparta’s ills if it meant that it created superlative soldiers: it did not. Spartan soldiers were average. The horror of the Spartan system, the nastiness of the agoge, the oppression of the helots, the regimentation of daily life, it was all for nothing. Worse yet, it created a Spartan leadership class that seemed incapable of thinking its way around even basic problems. All of that supposedly cool stuff made Sparta weaker, not stronger.

This would be bad enough, but the case for Sparta is worse because it – as a point of pride – provided nothing else. No innovation in law or government came from Sparta (I hope I have shown, if nothing else, that the Spartan social system is unworthy of emulation). After 550[BC], Sparta produced no trade goods or material culture of note. It produced no great art to raise up the human condition, no great literature to inspire. Despite possessing fairly decent farmland, it was economically underdeveloped, underpopulated and unimportant.

Athens produced great literature and innovative political thinking. Corinth was economically essential – a crucial port in the heart of Greece. Thebes gave us Pindar and was in the early fourth century a hotbed of military innovation. All three cities were adorned by magnificent architecture and supplied great art by great artists. But Sparta, Sparta gives us almost nothing.

Sparta was – if you will permit the comparison – an ancient North Korea. An over-militarized, paranoid state which was able only to protect its own systems of internal brutality and which added only oppression to the sum of the human experience. Little more than an extraordinarily effective prison, metastasized to the level of a state. There is nothing of redeeming value here.

Sparta is not something to be emulated. It is a cautionary tale.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

August 13, 2022

QotD: Erich von Manstein

One parallel between the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the conduct of the Second World War that has hitherto escaped notice concerns the relationship between the dictator and his generals. Just as the German General Staff obeyed Hitler’s orders, even when they knew him to be leading them not only to defeat but to depravity, so the Russian high command has capitulated to Putin despite realising that his war was not only a mistake but a crime.

In the Britain of the Sixties, a certain mystique still attached to the generals of the Third Reich. In their stylish uniforms and their gleaming jackboots, they had swaggered. Only two, Keitel and Jodl, were executed at Nuremberg; the rest got away with murder.

Even some of those who were convicted of war crimes had friends in high places. One of the most prominent was Erich von Manstein, the architect of many German victories both in the Battle of France and on the Eastern front. He was also complicit in the genocide of more than a million Jews and others by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen in Ukraine.

Yet Churchill was among those who successfully campaigned to have Manstein’s 18-year sentence reduced to 12, of which he served only four.

Manstein’s memoir Verlorene Siege (translated as Lost Victories) appeared in 1958, a key text in the mythology that depicted the Wehrmacht as “clean” and laid the blame for war crimes on Hitler. Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of the postwar Federal Republic, also played his part in the rehabilitation of Manstein, on the grounds that West German rearmament required a sharp distinction between the Nazis and an untainted military tradition as the basis for the new Bundeswehr.

Daniel Johnson, “The moral blindness of Putin’s generals”, The Critic, 2022-05-10.

August 11, 2022

Nostalgia seen as harmful

In The Critic, Michael Ledger-Lomas reviews a new book that is critical of Britain’s chronic case of nostalgia for “the good old days”:

Indulging in pained regret for lost times might seem a harmless pleasure, but Hannah Rose Woods is here to warn it has become a pathological “fixation”. The Right, she argues, has “weaponised” nostalgia, tapping “inchoate yearnings about fading pride and glory” to fuel hatred against historians who are simply “putting the facts back in” to the national “storybook”.

Apparently, the first cure for this “peculiarly English affliction” involves refuting errors and egregious simplifications in Tory talk about the national past. Woods is an inveterate Tweeter and her Rule, Nostalgia often works like a book-length version of the “Hi, historian here” threads that infest that medium.

The Government exhorted people to get through Covid by showing the Blitz spirit, but historians know German bombing caused as much fear and resentment as pride and resolve. Britons were supposed to Keep Calm and Carry On, “but this was a fantasy”, Woods writes, because the 1940s poster with that motto never entered circulation. The tea towels lied to us.

Woods is more productive when she probes nostalgia as a cluster of emotions, rather than condemning it as a set of errors. For like all emotions, it can be usefully historicised. This insight shapes the basic structure and approach of the book, which is more ironic than irate. Our times seem to be gripped by nostalgia for the days before yesterday, but the sixties, seventies and eighties abounded with yearning for the simplicities of the Second World War.

The thirties and forties were, in turn, full of voices lamenting what one of Orwell’s heroes called the “newness of everything”, pining for the sun-dappled afternoons of Edwardian England. The Edwardians themselves lamented the lost certainties of the high Victorian age and fretted that rural tranquillity was on the wane. And so on. Woods turns the periods of our history into Russian dolls of nostalgia, each nested within the other.

It is an engaging literary device which palls as succeeding chapters ask readers to re-enact their surprise that apparently stable times were consumed with anxiety about losing touch with tradition. Woods says the “calmly elegant Georgian heyday” fretted about whether Britain should go global or remain a tight little island, while it would be a “hard sell” to claim that the age of the Reformation and the Civil War was an “age of contentment and stability”. Well, quite.

The further Woods progresses away from the “rancid Englishness” of the present, the more forgiving she becomes of nostalgia — or at least of wistful absorption in the past, which is not quite the same thing. She rightly sees that nostalgia has generally not been an obstacle to rapid social change — what bolder Victorians would have called “progress” — but has offered psychological compensation for them.

August 7, 2022

QotD: The post-WW1 experiment in banning chemical weapons

This week, we’re going to talk briefly about why “we” – and by “we” here, I mean the top-tier of modern militaries – have generally eschewed the systematic or widespread use of chemical weapons after the First World War. And before you begin writing your comment, please note that the mountain of caveats that statement requires are here, just a little bit further down. Bear with me.

Now, when I was in school – this was a topic I was taught about in high school – the narrative I got was fairly clear: we didn’t use chemical weapons because after World War I the nations of the world got together and decided that chemical weapons were just too horrible and banned them, and that this was a sign of something called “progress“. In essence, the narrative I got was, we had become too moral for chemical weapons and so the “civilized” nations (a term sometimes still used unironically in this context) got together and enforced a moral taboo against chemical (and biological) weapons. And, we were told (this was, I should note, the late 90s and early aughts, long before the Syrian Civil War) that this taboo had mostly held.

Which was important, because in this narrative as it was impressed upon that younger version of me, the ban on chemical weapons showed the path towards banning all sorts of other terrible weapons: landmines, cluster-munitions and of course most of all, nuclear weapons. All we would need to do is for the “civilized” nations of the world to summon the moral courage to abandon such brutal weapons of war. Man, the end of history was nice while it lasted! But the example of the “successful” ban on chemical and biological weapons was offered as proof that the dream of a world without nuclear weapons was possible, if only we showed the same will.

When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put away childish things. But what was my teacher’s excuse? I guess the end of history was a hell of a drug.

[…] all three of these answers (including my high school answer) actually miss the point, because they all assume something fundamental: that chemical weapons are effective weapons, and so the decision not to use them is fundamentally moral, rather than practical.

Quite frankly, we don’t use chemical weapons for the same reason we don’t use war-zeppelin-bombers: they don’t work, at least within our modern tactical systems.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Don’t We Use Chemical Weapons Anymore?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-20.

August 3, 2022

QotD: Relative wealth among the Spartiates

… economic inequality among the spartiates was not new at any point we can see. But the nature of all of our sources – Plutarch, Xenophon, etc – is that they are almost always more interested in describing the ideal Spartan polity than the one that actually existed. And I want to emphasize […] that this ideal policy does not seem to ever have existed, with one author after another placing that ideal Sparta in the time period of the next author, who in turn informs us that, no, the ideal was even further back.

It is important to begin by noting that the sheer quantity of food the spartiates were to receive from their kleros would make almost any spartiate wealthy by the standards of most Greek poleis – spartiates, after all, lived a live of leisure (Plut. Lyc. 24.2) supported by the labor of slaves (Plut. Lyc. 24.3), where the closest they got to actual productive work was essentially sport hunting (Xen. Lac. 4.7). If the diet of the syssition was not necessarily extravagant, it was also hardly … well, Spartan – every meal seems to have included meat or at least meat-broth (Plut. Lyc. 12.2; Xen. Lac. 5.3), which would have been a fine luxury for most poorer Greeks. So when we are talking about disparities among the spartiates, we really mean disparities between the super-rich and the merely affluent. As we’ll see, even among the spartiates, these distinctions were made to matter sharply and with systematic callousness.

Now, our sources do insist that the Spartan system offered the Spartiates little opportunity for the accumulation or spending of wealth, except […] they also say this about a system they admit no longer functions … and then subsequently describe the behavior of wealthy Spartans in their own day. We’ve already noted Herodotus reporting long-standing wealthy elite spartiates as early as 480 (Hdt. 7.134), so it’s no use arguing they didn’t exist. Which raises the question: what does a rich Spartiate spend their wealth on?

In some ways, much the same as other Greek aristocrats. They might spend it on food: Xenophon notes that rich spartiates in his own day embellished the meals of their syssitia by substituting nice wheat bread in place of the more common (and less tasty) barley bread, as well as contributing more meat and such from hunting (Xen. Lac. 5.3). While the syssitia ought to even this effect out, in practice it seems like rich spartiates sought out the company of other rich spartiates (that certainly seems to be the marriage pattern, note Plut. Lys. 30.5, Agis. 5.1-4). Some spartiates, Xenophon notes, hoarded gold and silver (Xen Lac. 14.3; cf. Plut. Lyc. 30.1 where this is supposedly illegal – perhaps only for the insufficiently politically connected?). Rich spartiates might also travel and even live abroad in luxury (Xen. Lac. 14.4; Cf. Plut. Lyc. 27.3).

Wealthy spartiates also seemed to love their horses (Xen. Ages. 9.6). They competed frequently in the Olympic games, especially in chariot-racing. I should note just how expensive such an effort was. Competing in the Olympics at all was the preserve of the wealthy in Greece, because building up physical fitness required a lot of calories and a lot of protein in a society where meat was quite expensive. But to then add raising horses to the list – that is very expensive indeed (note also spartiate cavalry, Plut. Lyc. 23.1-2). Sparta’s most distinguished Olympic sport was also by far the most expensive one: the four-horse chariot race.

In other ways, however, the spartiates were quite unlike other Greek aristocrats. They do not seem to have patronized artists and craftsmen. The various craft-arts – decorative metalworking, sculpture, etc – largely fade away in Sparta starting around 550 B.C. – it may be that this transition is the correct date for the true beginning of not only “Spartan austerity” but also the Spartan system as we know it. There are a few exceptions – Cartledge (1979) notes black-painted Laconian finewares persist into the fifth century. Nevertheless, the late date for the archaeological indicators of Spartan austerity is striking, as it suggests that the society the spartiates of the early 300s believed to have dated back to Lycurgus in the 820s may well only have dated back to the 550s.

The other thing we see far less of in Sparta is euergitism – the patronage of the polis itself by wealthy families as a way of burnishing their standing in society. While there are notable exceptions (note Pritchard, Public Spending and Democracy in Classical Athens (2015) on the interaction and scale of tribute, taxes and euergitism at Athens), most of the grand buildings and public artwork in Greek cities was either built or maintained by private citizens, either as voluntary acts of public beneficence (euergitism – literally “doing good”) or as obligations set on the wealthy (called liturgies). Sparta had almost none of this public building in the Classical period – Thucydides’ observation that an observer looking only at the foundation of Sparta’s temples and public buildings would be hard-pressed to say the place was anything special is quite accurate (Thuc. 1.10.2). There are a handful of exceptions – the Persian stoa, a few statue groups, some hero reliefs, but far, far less than other Greek cities. In short, while other Greek elites felt the need – or were compelled – to contribute some of their wealth back to the community, the spartiates did not.

Passing judgment on those priorities, to a degree, comes down to taste. It is easy to cast the public building and patronage of the arts that most Greek elites engaged in as crass self-aggrandizement, wasting their money on burnishing their own image, rather than actually helping anyone except by accident. And there is truth to that idea – the Greek imagination has little space for what we today would call a philanthropist. On the other hand – as we’ll see – a handful of spartiates will come to possess a far greater proportion of the wealth and productive capacity of their society. Those wealthy spartiates will do even less to improve the lives of anyone – even their fellow spartiates. Moreover, following the beginning of Spartan austerity in the 550s, Sparta will produce no great artwork, no advances in architecture, no great works of literature – nothing to push the bounds of human achievement, to raise the human spirit.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part IV: Spartan Wealth”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-29.

July 27, 2022

When the founder of the SAS was captured by Italian troops in 1943

In The Critic, Saul David describes what happened when Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling was captured during his “most hare-brained scheme” to link up the troops of Britain’s First and Eighth armies in Tunisia:

In January 1943 Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling, founder of the SAS, was flown to Rome for interrogation. He had been captured by the Italians on his “most hare-brained scheme yet” — leading a small raiding party deep into enemy territory in Tunisia to attack lines of communication, reconnoitre the terrain and become the first Eighth Army unit to link up with the First Army advancing from the west.

Cautious when speaking to the Italians, he was “vain and voluble” in conversation with a fellow “captive”, Captain John Richards. Unbeknown to Stirling, Richards was an Anglo-Swiss stool pigeon, Theodore Schurch, who had deserted from the British army and was working for fascist intelligence.

Prior to Schurch’s court-martial for treachery in late 1945, Stirling denied he had revealed any sensitive information. If he had, it was inaccurate and “designed to deceive”. This was a lie, told to protect Stirling’s reputation. In fact, as the British authorities knew all too well from intercepted signals, Stirling had told Richards vital details about current SAS operations, including the location of patrols and their orders. He had even given them the name of his probable replacement as SAS commander: Paddy Mayne.

The story of Stirling’s unfortunate encounter with Schurch has been told before, notably by Ben Macintyre in his bestselling SAS: Rogue Heroes. But Macintyre underplays Stirling’s indiscretion and fails to link it to the many other examples of the SAS commander’s recklessness and poor judgement of character. For Gavin Mortimer, on the other hand, both the capture and loose talk were typical of a man who was “imaginative, immature, immoderate and ill-disciplined”. Small wonder that even his own brother Bill thought he would be better off in a prisoner-of-war camp.

The subtitle of Mortimer’s book — a carefully researched and impeccably sourced take-down of the legendary special forces pioneer — is a corrective to the flattering but inaccurate nickname that was first coined for Stirling by British tabloids during the Second World War. “When word reached Cairo of the Phantom Major moniker,” writes Mortimer, “it must have sparked a mix of hilarity and indignation. All the falsehoods and fabrications would have been harmless enough had Stirling not stolen the valour of his comrades.”

Thread by thread, Mortimer unpicks the myth of Stirling’s life and war service that the subject and his fawning admirers had so carefully constructed, both during and after the war. Stirling was not training in North America for an attempt on Mount Everest’s summit when war broke out in 1939, as he later claimed, but rather working as a ranch hand because his exasperated family hoped it might give the feckless youth some focus and direction.

July 20, 2022

The Myth of Rosie the Riveter – On the Homefront 016

World War Two

Published 19 Jul 2022With American men going off to fight the war, there are concerns about a labor shortage. Enter Rosie the Riveter. The women who answered the “We Can Do It” call and entered the factories. But did she really exist?

(more…)

July 8, 2022

QotD: Sparta’s vaunted hoplite phalanx differed little from hoplite armies from other Greek cities

The hoplite phalanx was the common fighting style of essentially all Greek poleis. It was not unique to Sparta.

That comes with all sorts of implications. The Spartans used the same military equipment as all of the other Greeks: a thrusting spear (the dory), a backup sword (a xiphos or kopis; pop-culture tends to give Spartans the kopis because it looks cool, but there is no reason to suppose they preferred it), body armor (either textile or a bronze breastplate), one of an array of common Greek helmet styles, and possibly greaves. We might expect the Spartiates – being essentially very wealthy Greeks – to have equipment on the high end of the quality scale, but the Perioikoi, and other underclasses who fought with (and generally outnumbered) the Spartiates will have made up the normal contingent of “poor hoplites” probably common for any polis army.

Xenophon somewhat oddly stops to note that the Spartiates were to carry a bronze shield (kalken aspida; Xen. Lac. 11.3 – this is sometimes translated as “brass” – it is the same word in Greek – but all Greek shield covers I know of are bronze). This is not the entire shield, as in [the movie] 300 – that would be far too heavy – but merely a thin (c. 0.25mm) facing on the shield. It’s odd that Xenophon feels the need to tell us this, because this was standard for Greek shields. Perhaps poorer hoplites couldn’t afford the bronze facing and used a cheaper material (very thin leather, essentially parchment, is common in many other shield traditions) and Xenophon is merely noting that all of the Spartiates were wealthy enough to afford the fancy and expensive sort of shield (it has also been supposed that elements of this passage have dropped out and it would have originally included a complete panoply, in which case Xenophon is just uncharacteristically belaboring the obvious).

The basics of the formation – spacing, depth and so on – also seem to have been essentially the same. The standard depth for a hoplite phalanx seems to have been eight (-ish; there’s a lot of variation). The Spartans seem to have followed similar divisions with a fairly wide range of depths, perhaps trending towards thinner lines in the fourth century than in the fifth, though certainty here is difficult. The drop in depth may be a consequence of manpower depletion, but it may also indicate a greater faith held by Spartan commanders of their line’s ability to hold. Depth in a formation is often about morale – the deeper formation feels safer, which improves cohesion.

It’s hard to say if the Spartan phalanx was more cohesive. It might have been, at least for the Spartiates. The lifestyle of the Spartiates likely created close bonds which might have aided in holding together in the stress of combat – but then, this was true of essentially every Greek polis to one degree or another. The best I can say on this point is that the Spartan battle record – discussed at length below – argues against any large advantage in cohesion.

That said, the Spartan battle order does seem to have been notably different in two respects:

First: it had a much higher ratio of officers to regular soldiers. This was clearly unusual and more than one ancient source remarks on the fact (Thuc. 5.68; Xen. Lac. 11.4-5, describing what may be slightly different command systems). Each file was under the command of the man in front of it (Xen. Lac. 11.5). Six files made an enomotia (commanded by an enomotarchos); two of these put together were commanded by a pentekonter (lit: commander of fifty, although he actually had 72 men under his command); two of those form a lochos (commanded by a lochagos) and four lochoi made a mora, commanded by a polemarchos (lit: war-leader) – there were six of these in Xenophon’s time. Compared to most Greek armies of the time, that’s a lot of officers, which leads to:

Second: it seems to have been able to maneuver somewhat more readily than a normal phalanx. This follows from the first. Smaller tactical subdivisions with more command personnel made the formation more agile. Xenophon clearly presents this ability as exceptional, and it does seem to have been (Xen. Lac. 11.4). Hoplite armies victorious on one flank often had real trouble reorganizing those victorious troops and wheeling them to flank and roll up the rest of the line (e.g. the Athenians at Delium, Thuc. 4.96.3-4). The Spartans were rather better at this (e.g. at Mantinea, Thuc. 5.73.1-4). They also seem to have been better at marching and moving in time.

Now, I do not want to over-sell this point. We’re comparing the Spartans to other hoplite forces which – in the fifth century especially – were essentially dumbfire missiles. The general (or generals) point the phalanx at the enemy, hit “go” and then hope for the best. Really effective command – what Everett Wheeler refers to as the general as “battle manager” – really emerges in the fourth century, mostly after Spartan power was already broken (E. Wheeler, “The General as Hoplite” in Armies of Classical Greece, ed. Wheeler (2007)). While “right wing, left wheel” is hardly the most complicated of maneuvers (especially given that the predictable rightward drift of hoplite armies in battle meant that it could be planned for), compared to the limitations of most hoplite forces, it marked the Spartans out as unusually adept.

More complicated Spartan maneuvers often went badly. Spartan forces at Plataea (479 – Hdt. 9.53) failed to effectively redeploy under orders, precipitating an unintended engagement. Plugging a gap in the line once the advance was already underway, but before battle was joined (something Roman armies did routinely) was also apparently beyond the capabilities of a Spartan army (Thuc. 5.72). While the Spartans are often shown in popular culture with innovative tactical formations – like the anti-cavalry wedge or anti-missile shield-ball (both of which, to be clear, are nonsense) formations in 300 – in practice the Spartan army was tactically uncreative. Like every other hoplite army, the Spartans formed a big rectangle of men and smashed it into the front of the enemy’s big rectangle of men. Notably, as we’ll see, the Spartans made limited and quite poor use of other arms, like light infantry or cavalry, even compared to other Greek poleis (and the bar here is very low, Greek combined arms, compared to say, Roman or Macedonian or Persian combined arms, was dismal). If anything, the Spartans were less adaptable than other hoplites.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VI: Spartan Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-20.

June 30, 2022

QotD: Sparta had Lycurgus, while Athens had Solon … who at least actually existed

Lycurgus was the name the Spartans gave for their mythical founder figure, a Spartan who had supposedly lived in the late 9th century and had set up the Spartan society as we see it in the classical period. Almost all of our details for his life come from a biography by Plutarch, written c. 100 A.D. (date to be significant in a moment). The story the Spartans told went thusly:

Once upon a time … there was a Spartan named Lycurgus, and he was the very best Spartan …

Lycurgus had been the younger brother of one of Sparta’s two kings, but had left Sparta to travel when his brother died, so that he would be no threat to his young nephew.

After a time, the Spartans begged Lycurgus to come back and reorganize society, and Lycurgus – with the blessing of the Oracle at Delphi – radically remade Spartan society into the form it would have for the next 400 years. He did not merely change the government, but legislated every facet of life, from child-rearing to marriage, to the structure of households, the economic structure, everything. Once he had accomplished that, Lycurgus went back to Delphi, but before he left he made all the Spartans promise not to change his laws until he returned. Once the Oracle told him his laws were good, he committed suicide, so that he would never return to Sparta, thus preventing his laws from ever being overturned. So the Spartans never changed Lycurgus’ laws, which had been declared perfect by Apollo himself. Subsequently, the Spartans accorded Lycurgus divine honors, and within Sparta he was worshiped as a god.

And that’s how Lycurgus remade Sparta. The End.

The role Lycurgus serves in the sources is as the perfect, infallible founder figure. No less than the Oracle at Delphi – the divine word of Apollo – declared Lycurgus a god (Hdt. 1.65.3). For later sources who, we must stress – believe their own religion (as people everywhere are wont to do) – that means, essentially a priori that Lycurgus’ “constitution” must be practically flawless and all flaws must stem from its imperfect implementation.

But – wait a second – what is our evidence for the actual person of Lycurgus or the character of the state he set up?

Remember how I said Lycurgus is dated to the late 9th century – specifically the 820s B.C. or so. That’s a huge problem. The earliest Greek literature comes from around (very roughly – there is deep scholarly debate here that I’m glossing over) the mid-8th century (c. 750 or so) and is entirely mythological in nature. The first actual history is Herodotus, writing in the mid-400s. The earliest historical event we have evidence for is the Lelantine War (c. 700ish), at least a century after the life of Lycurgus. None of our sources have anything to go on about Lycurgus – save for what the Spartans – who already worship this figure as a god – tell them. Crucially, Tyrtaeus, writing in the 650s B.C., while he does mention the rhetra (an oracle the Spartans received concerning the arrangement of their government) does not mention Lycurgus (although Plutarch is quick to connect the two, Plut. Lyc. 6.5), meaning that the earliest source for Lycurgus’ existence is Herodotus.

Wait, it gets even better – the one thing we do know about Lycurgus’ laws is that they were not written down (Plut. Lyc. 13.1). Also, Lycurgus supposedly took steps to prevent his remains from returning to Sparta (Plut. Lyc. 29.5-6, but cf. 31.4) and no continued family line, which seems like exactly the sort of explanation you put at the end of a good campfire story for why there was absolutely no trace of such an important man save his legend. So not only the details of Lycrugus’ life, but also the society he created will have lived as oral tradition – potentially changing from one telling to the next, being embellished or expanded – for generations before being committed to the permanent, unchanging memory of written history.

In short, our only evidence for Lycurgus are the campfire stories told about him by people who worshiped him as a god, as related to individuals centuries later. Which is to say that, by historical standards, there is no reliable evidence at all that Lycurgus existed.

[…]

Lycurgus is often set against Solon – the early 6th century Athenian reformer. It is true that Athenians also tend to attribute things to Solon that were later developments, but we need to note the key differences: Solon comes two centuries after Lycurgus (thus, unlike Lycurgus, in the historical period), didn’t receive divine honors and most importantly writes to us (he wrote poetry, some of which survives), so that we can know he was an actual real person. Asking students – as I have seen done – to compare a real, flawed reformer with an idealized, semi-mythical demi-god without any kind of guidance as to the nature of these two figures is, quite frankly, educational malpractice.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part III: Spartan Women”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-29.

June 2, 2022

“Like many problems in American history, recycling began as a moral panic”

Jon Miltimore recounts the seminal event that kicked off the recycling pseudo-religion in North America:

The frenzy began in the spring of 1987 when a massive barge carrying more than 3,000 tons of garbage — the Mobro 4000 — was turned away from a North Carolina port because rumor had it the barge was carrying toxic waste. (It wasn’t.)

“Thus began one of the biggest garbage sagas in modern history,” Vice News reported in a feature published a quarter-century later, “a picaresque journey of a small boat overflowing with stuff no one wanted, a flotilla of waste, a trashier version of the Flying Dutchman, that ghost ship doomed to never make port.”

The Mobro was simply seeking a landfill to dump the garbage, but everywhere the barge went it was turned away. After North Carolina, the captain tried Louisiana. Nope. Then the Mobro tried Belize, then Mexico, then the Bahamas. No dice.

“The Mobro ended up spending six months at sea trying to find a place that would take its trash,” Kite & Key Media notes.

America became obsessed with the story. In 1987 there was no Netflix, smartphones, or Twitter, so apparently everyone just decided to watch this barge carrying tons of trash for entertainment. The Mobro became, in the words of Vice, “the most watched load of garbage in the memory of man.”

The Mobro also became perhaps the most consequential load of garbage in history.

“The Mobro had two big and related effects,” Kite & Key Media explains. “First, the media reporting around it convinced Americans that we were running out of landfill space to dispose of our trash. Second, it convinced them the solution was recycling.”

Neither claim, however, was true.

The idea that the US was running out of landfill space is a myth. The urban legend likely stems from the consolidation of landfills in the 1980s, which saw many waste depots retired because they were small and inefficient, not because of a national shortage. In fact, researchers estimate that if you take just the land the US uses for grazing in the Great Plains region, and use one-tenth of one percent of it, you’d have enough space for America’s garbage for the next thousand years. (This is not to say that regional problems do not exist, Slate points out.

The widespread imposition of recycling mandates across North America was probably an inevitable reaction to the voyage of the Mobro. For many people, this was the end of the story, as things that were previously just buried in landfill sites would now be safely and efficiently put back into the economy as re-used, re-purposed, or actual recycled products. Win-win, right?

Sadly, the economic case for recycling many items is weak to non-existant. The demand for recycled materials was lower than predicted and often only maintained through subsidies and hidden incentives that couldn’t last forever. Once the incentives went away, so did much of the created demand. Worse, the way a lot of the stream of recyclable materials was handled was by shipping it off to China or certain developing nations — in effect, paying them to take the problem off the hands of western governments. This resulted in even more problems:

Americans who’ve spent the last few decades recycling might think their hands are clean. Alas, they are not. As the Sierra Club noted in 2019, for decades Americans’ recycling bins have held “a dirty secret”.

“Half the plastic and much of the paper you put into it did not go to your local recycling center. Instead, it was stuffed onto giant container ships and sold to China,” journalist Edward Humes wrote. “There, the dirty bales of mixed paper and plastic were processed under the laxest of environmental controls. Much of it was simply dumped, washing down rivers to feed the crisis of ocean plastic pollution.”

It’s almost too hard to believe. We paid China to take our recycled trash. China used some and dumped the rest. All that washing, rinsing, and packaging of recyclables Americans were doing for decades — and much of it was simply being thrown into the water instead of into the ground.

The gig was up in 2017 when China announced they were done taking the world’s garbage through its oddly-named program, Operation National Sword. This made recycling much more expensive, which is why hundreds of cities began to scrap and scale back operations.

May 26, 2022

Alex Tabarrok reviews The Parent Trap

At Marginal Revolution, Alex Tabarrok looks at Nate G. Hilger’s new book, The Parent Trap:

Hilger argues that the problems of poverty, pathology and inequality that bedevil the United States are not primarily due to poor schools, discrimination, or low incomes per se. The primary cause is parents: parents who are unable to teach their children the skills that are necessary to succeed in the modern world. Since parents can’t teach the necessary skills, Hilger calls for the state to take their place with a dramatic expansion of not just child care but collective parenting.

Let’s unpack some details. Begin with schooling. It’s very common to bemoan the state of schools in the “inner city” or to complain about “local financing” which supposedly guarantees that poor counties will have underfunded schools. All of this, however, is decades out-of-date.

A hundred years ago there really were massive public-school resource gaps by class and race. These days, however, state and federal spending play a larger role than local property tax revenue and distribute educational resources more progressively … In fact, when we include federal aid, 42 states spent more on poor school districts than on rich school districts in 2012. The same pattern holds between schools within districts

… The highest spending districts are large urban centers such as New York City, Boston and Baltimore. These cities spend large sums to educate rich and poor children alike. p. 10-11

Hilger is correct. No matter what you saw on The Wire, Baltimore spends more than sixteen thousand dollars per student, among the highest in the nation in large school districts and above average for the nation as a whole. Public schools are quite egalitarian in funding with any bias running towards more funding for poorer districts.

Schools, Hilger writes are “actually the smallest and most equalizing part of a much larger skill-building system.” The real problem, says Hilger, are parents.

But what about discrimination? When it comes to wage discrimination, Hilger is brutally honest:

If we compare individuals with similar cognitive test scores, Black college graduates earn higher wages than white college graduates. Studies that don’t control for test score differences but examine earnings gaps within specific professions — lawyers, physicians, nurses, engineers, scientists — tend to find Black workers earn zero to 10 percent less than white workers. These gaps could reflect discrimination, unmeasured skill differences, or other factors such as geography. In any case, such gaps are small compared to the 50 percent overall Black-white earnings gap and reinforce the idea that closing skills gaps would go a long way toward closing income gaps.

Hilger argues that racism does play an important role in explaining Black-white wage differentials but it’s the historical racism that made black parents less skilled and less able to pass on skills to their children. In the twentieth century, Asians, Hilger argues, were discriminated against in the United States at least much as Black Americans. But the Asians that came to the United States had high skills while the legacy of slavery meant that Black Americans began with low skills. Asians, therefore, were better able to overcome discrimination. The success of Nigerians and Jamaican immigrants in the United States also speaks to this point. (Long time readers may recall that in 2016 I dubbed Hilger’s paper on Asian Americans and Black Americans the Politically Incorrect Paper of the Year.)

April 23, 2022

Historic “innovation prizes” (somewhat) debunked

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes does a bit of heavy lifting to debunk some accreted nonsense about the origins and success of early innovation prizes:

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Cloudsley Shovell (1650-1707).

Portrait by unknown artist from the National Maritime Museum collection via Wikimedia Commons.

Yesterday I had a piece in Works in Progress magazine, on the best ways to design modern innovation prizes — and why many of them fail.

I examined the famous “Longitude Prize” of 1714, and in the process busted some major myths about it. Almost every element of the popular story is wrong — something that experts on the topic like Richard Dunn and Rebekah Higgitt have been going on about for years. The popular story’s hero, John Harrison, often portrayed as an inventor shunned by a haughty scientific establishment, actually received massive amounts of funding from the committee for awarding the prize. The story’s villain, the Astronomer Royal Neville Maskelyne, was no villain at all. And there’s very little evidence that the prize actually incentivised people to innovate. The Board of Longitude, for that matter, ended up more like a grant-giving agency — a kind of navigation-themed DARPA — than just a committee of prize judges.

You can read the full piece here.

So what is the rest of this week’s newsletter about? Well, I’d like to take the chance to bust even more myths about innovation prizes!

Let’s start with a fairly small one, to do with longitude, that I’d missed. Take the narrative about the 1707 naval disaster off the Isles of Scilly, which led to the demise of the wonderfully-named admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell. The disaster is usually cited as having been the direct cause of the institution of the 1714 reward, and, of course, gives most Youtubers, bloggers, and TV presenters discussing longitude the opportunity to say the name “Sir Cloudesley Shovell”. Who wouldn’t?

I had already been sceptical of the disaster’s relevance to Parliament’s creation of the longitude reward, because of the seven-year delay. I had then noticed, when researching for the piece, that the disaster was hardly mentioned at all by those lobbying for the reward, by those consulted on it, or by the MPs who voted on it. It seemed to be irrelevant as a cause, so I repurposed that part of the popular story to simply use as a general example of a naval disaster caused by not knowing one’s position at sea.

But even my downgrading of its relevance, it turns out, may have been over-generous. Yesterday, after I published my piece, Richard Dunn pointed out to me that not only was the 1707 disaster irrelevant as a cause of the 1714 reward, but that the disaster itself may not have had very much to do with a specific failure to find longitude. It certainly wasn’t singled out as a cause at the time.

As for the actual causes, they were probably compass error, inconsistent charts, and even uncertainty over the fleet’s latitude, not just its longitude. And to the extent that not knowing the fleet’s longitude appears to have been a major part of the problem, it was also related to failures to accurately calculate longitude on land — something that could already be done using existing techniques. The navigational text-books, for example, disagreed on the position of Cape Spartel, in Morocco, from which the fleet departed and took its bearings. As the maritime historian William E. May put it, when he looked into the detail of the fleet’s route and navigational measurements, “the errors in longitudes in the accepted text-books must have introduced a danger just as great as any errors in reckoning the longitude.”

April 17, 2022

Queen Victoria’s Easter Cake

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 23 Mar 2021Help Support the Channel with Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/tastinghistory

Tasting History Merchandise: crowdmade.com/collections/tastinghistoryFollow Tasting History here:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tastinghist…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TastingHistory1

Tiktok: TastingHistory

Reddit: r/TastingHistory

Discord: https://discord.gg/d7nbEpyLINKS TO INGREDIENTS & EQUIPMENT**

Sony Alpha 7C Camera: https://amzn.to/2MQbNTK

Sigma 24-70mm f/2.8 Lens: https://amzn.to/35tjyoW

Self Rising Flour: https://amzn.to/3cKxIoy

Almond Flour: https://amzn.to/3cGN9Ox

Mixed Peel: https://amzn.to/3lp6MP2

Currants: https://amzn.to/3bWEXe4

Castor Sugar: https://amzn.to/3vJMjJR

8 Inch Cake Pan: https://amzn.to/3f3fL7JLINKS TO SOURCES**

Pot Luck: British Home Cookery Book by May Byron: https://amzn.to/3r1qQIp

The Chronicle of Battle Abbey: https://amzn.to/3ePfrco

Cake: A Slice of History by Alysa Levene: https://amzn.to/2Q7JOAs**Some of the links and other products that appear on this video are from companies which Tasting History will earn an affiliate commission or referral bonus. Each purchase made from these links will help to support this channel with no additional cost to you. The content in this video is accurate as of the posting date. Some of the offers mentioned may no longer be available.

Subtitles: Jose Mendoza

#tastinghistory #easter #simnelcake