In City Journal, Nicole Gelinas recounts the tale of the fateful merger of two great American railroad systems that lasted just long enough to support massive financial chicanery before descending into inevitable bankruptcy:

More than 50 years on now, the spectacular collapse of the Penn Central railroad in 1970 is little remembered today, but its legacy is still with us — not so much as a warning, but as a prelude: to New York City’s own near-bankruptcy in the 1970s; to four decades of financial engineering, beginning in the 1980s; to the 2001 Enron downfall; to the 2008 financial crisis and its “too big to fail” bailouts — and yes, even to the public discontent that elected President Donald Trump.

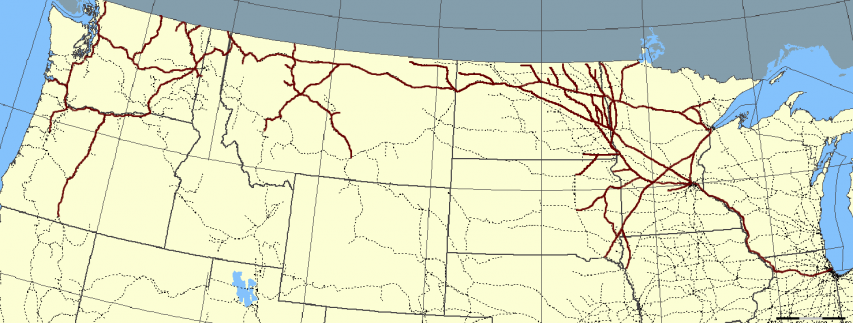

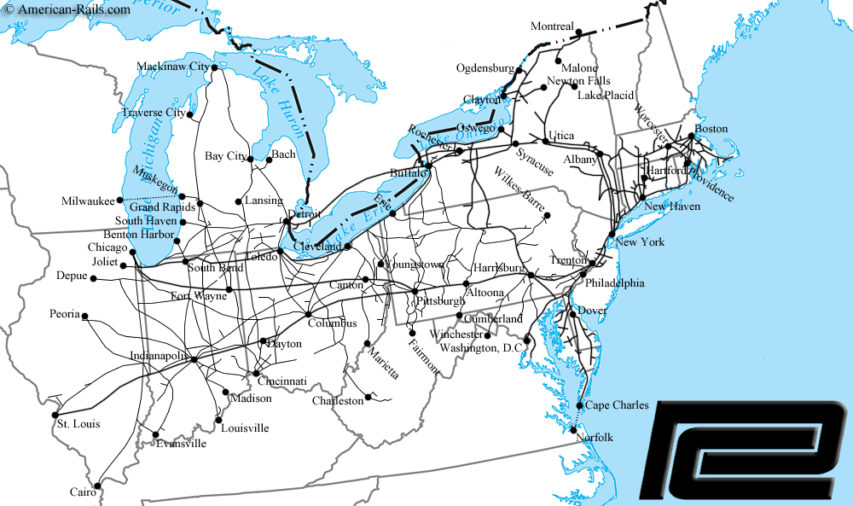

As America emerged from World War II, most people would have laughed at the idea of the nation’s two premier freight and passenger railroads, the Pennsylvania and the New York Central, going broke in a quarter-century’s time. By design, the Pennsy and the Central were not fierce competitors but complementary “frenemies” that had long agreed not to undercut one another’s monopoly profits. From Massachusetts to Missouri, the two railroads dominated freight and passenger travel in the northeast quarter of the United States, with nearly 21,000 miles of track between them.

Yet even as America built its powerhouse postwar economy, the railroads struggled. As Joseph R. Daughen and Peter Binzen write in The Wreck of the Penn Central, their cult-classic chronicle of the Penn Central’s demise, during the war the then-separate railroads had been running their equipment 24 hours a day to transport troops and supplies, leaving them with “worn-out” equipment.

In the fifties and sixties, moreover, new competitive pressures prevented them from catching their breath. Trucks competed with the railroads for freight hauling via the new, free highways the nation was building. Commuter-rail passengers moved to the highways as well, while long-haul rail passengers took to the skies. The railroads’ decline accelerated in the sixties, partly because of the collapse of northeast manufacturing.

In 1962, the two companies decided to merge. But railroading was one of the most heavily regulated industries in the United States, so the merger took six years, as it wound its way through multiple levels of public approval for the creation of the 100,000-worker, 100,000-shareholder, 100,000-creditor behemoth. Meantime, government-set rates already fell short of the railroads’ long-term costs.

The combined entity that would become the Penn Central made significant concessions to win political support for the merger, including no-layoff pledges that would hamper its ability to cut spending and a promise to take on the independent (and chronically insolvent) New York, New Haven, and Hartford passenger railroad.

After the merger, the railroads discovered that they had incompatible computer systems, which threw railyards into chaos and angered customers. The Penn Central’s three top officials, too, were incompatible. They “scarcely spoke to one another,” write Daughen and Binzen. Stuart Saunders, the board chairman, was a political guy. Alfred Perlman, the president, was a trains guy. These different outlooks could have complemented each other, but personalities got in the way. Rounding out this dysfunctional triumvirate was Penn vet David Bevan, the top financial official, perpetually “angry and humiliated” at not being picked for the top job.

Penn Central route map from us.leforum.eu

http://us.leforum.eu/t1355-Photos-du-Penn-Central-PC.htm

H/T to Ed Driscoll at Instapundit, who also posted this video the combined entity put together to celebrate the merger: