The environmentalist aesthetic is to love villages and despise cities. My mind got changed on the subject a few years ago by an Indian acquaintance who told me that in Indian villages the women obeyed their husbands and family elders, pounded grain, and sang. But, the acquaintance explained, when Indian women immigrated to cities, they got jobs, started businesses, and demanded their children be educated. They became more independent, as they became less fundamentalist in their religious beliefs. Urbanization is the most massive and sudden shift of humanity in its history.

Stewart Brand, “Environmental Heresies”, Technology Review, 2005-05

June 28, 2021

QotD: Urbanization

June 18, 2021

Innovation was minimal in the Roman Empire, because slave societies think they don’t need new inventions

Mark Koyama writes for the Foundation for Economic Education on the similarities and differences of the economy of the Roman Empire at its second-century peak and the booming European economies of the 17th and early 18th centuries:

“The Consummation of Empire” from the painting series “The Course of the Empire” by Thomas Cole (1801-1848).

New York HIstorical Society collection via Wikimedia Commons.

The most obvious institutional difference between the ancient world and the modern was slavery. Recently historians have tried to elevate slavery and labor coercion as a crucial causal mechanism in explaining the industrial revolution. These attempts are unconvincing […] but slavery certainly did dominate the ancient economy.

In its attempt to draw together the various strands through which slavery permeated the ancient economy, [Aldo] Schiavone’s chapter “Slaves, Nature, Machines” [in The End of the Past] is a tour de force. At once he captures the ubiquity of slavery in the ancient economy, its unremitting brutality — for instance, private firms that specialized in branding, retrieving, and punishing runaway slaves — and, at the same time, touches the central economic questions raised by ancient slavery: to what extent was slavery crucial to the economic expansion of the period between 200 BCE and 150 AD? And did the prevalence of slavery impede innovation?

It is impossible to do justice to the argument in a single post. Suffice to say that after much discussion, and many fascinating interludes, Schiavone suggests that ultimately the economic stagnation of the ancient world was due to a peculiar equilibrium that centered around slavery.

One can think of this equilibrium as resting on two legs. The first is the observation that the apparent modernity of the ancient economy — its manufacturing, trade, and commerce rested largely on slave labor. The expansion of trade and commerce in the Mediterranean after 200 BC both rested on and drove the expansion of slavery. Here Schiavone notes that the ancient reliance on slaves as human automatons — machines with souls — removed or at least weakened, the incentive to develop machines for productive purposes.

The existence of slavery, however, was not the only reason for the neglect of productive innovation. There was also a specific cultural attitude that formed the second leg of the equilibrium:

None of the great engineers and architects, none of the incomparable builders of bridges, roads, and aqueducts, none of the experts in the employment of the apparatus of war, and none of their customers, either in the public administration or in the large landowning families, understood that the most advantageous arena for the use and improvement of machines — devices that were either already in use or easily created by association, or that could be designed to meet existing needs — would have been farms and workshops

The relevance of slavery colored ancient attitudes towards almost all forms of manual work or craftsmanship. The dominant cultural meme was as follows: since such work was usually done by the unfree, it must be lowly, dirty and demeaning:

technology, cooperative production, the various kinds of manual labor that were different from the solitary exertion of the peasants on his land — could not but end up socially and intellectually abandoned to the lowliest members of the community, in direct contact with the exploitation of the slaves, for whom the necessity and demand increased out of all proportion … the labor of slaves was in symmetry with and concealed behind (so to speak) the freedom of the aristocratic thought, while this in turn was in symmetry with the flight from a mechanical and quantitative vision of nature

Thus this attitude also manifests itself in the disdain the ancients had for practical mechanics:

Similar condescension was shown to small businessmen and to most trade (only truly large-scale trade was free from this taint). The ancient world does not seem to have produced self-reproducing mercantile elites. Plausible this was in part because of the cultural dominance of the landowning aristocracy.

The phenomenon coined by Fernand Braudel, the “Betrayal of the Bourgeois”, was particularly powerful in ancient Rome. Great merchants flourished, but “in order to be truly valued, they eventually had to become rentiers, as Cicero affirmed without hesitation: ‘Nay, it even seems to deserve the highest respect, if those who are engaged in it [trade], satiated, or rather, I should say, satisfied with the fortunes they have made, make their way from port to a country estate, as they have often made it from the sea into port. But of all the occupations by which gain is secured, none is better than agriculture, none more delightful, none more becoming to a freeman'” (Schiavone, 2000, 103).

Such a cultural argument fits perfectly with Deirdre McCloskey’s claim in her recent trilogy that it was the adoption of bourgeois cultural norms and specifically bourgeois rhetoric that distinguished and caused the rise of north-western Europe after 1650.

June 14, 2021

Movies based on “classic literature”

Severian considers the relative glut of movies more-or-less based on the classics of literature from his formative years:

When I was a young buck, there was a fad for making movies out of “classic literature”. Scads of chick flicks, of course — Jane Austen’s complete works, the Brontës, and so on — but they also took a stab at Shakespeare. Mostly they stuck to the comedies — and trust me, watching Keanu Reeves trying to handle Much Ado About Nothing is hilarious, in all the wrong ways — but they’d occasionally give the tragedies a shot. Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet is pretty good despite all the distracting cameos, his Othello is at least sincere (ye gods, imagine trying to make that today!), I think I’m forgetting a few. Mel Gibson gave Hamlet a go back in the early 1990s, and so on. Again, I’m pretty sure I’m forgetting a few.

It always struck me as odd. Unless they timed the theatrical releases to midterm and finals week, hoping to hoover up the dollars of desperate sophomores who didn’t do the homework, it didn’t make much sense, marketing-wise. We were a much more culturally literate people once, it’s true*, but there’s just not much of an audience for the Bard anymore. Nor was it a case of SJWs trying to destroy something good just on general principles. I’m sure Gwyneth Paltrow was bad as Emma, but the idea of retconning every single female in the Western Canon into a Strong, Confident Woman(TM) was still in its infancy. My only other guess was that, since college enrollments were skyrocketing, maybe the parents of all those first-gen college kids were feeling mal-educated and trying to catch up …? Lame, I know, but it was the best I could do.

Looking back on it now, I see my problem: I was looking at it from the demand side. Silly and naive as I was, I assumed that Hollywood’s primary concern was making money, so they went out and found what the people wanted to see, then gave it to them. For instance, I thought Titanic was going to be a huge flop. I mean, the boat sinks. We know that. How do you squeeze any dramatic tension out of it? I should’ve realized they’d be playing it as a doomed-lovers tragedy — girls love that shit, what with the big flouncy costumes and all. Once I realized that, I thought I had it all figured out — every girl I, personally, knew found the works of Jane Austen tedious, but that’s because (I reasoned) you have to supply the images for yourself. Put Hunky McBeef up there in breeches and a peruke, Waify Beecup in a Regency dress, and it’s chick crack …

Or so I thought. Looking back on it now, that’s as dumb as my opinion that Titanic would bomb. Hollywood doesn’t care what you want. I doubt if Hollywood has ever cared what you want, but if they ever did, that time probably ended in tandem with Clara Bow’s career. Hollywood wants what they want, and so will you, because whaddaya gonna do, not watch it? The reason they made all those “classic literature” films in the 1990s, then, wasn’t because they thought we wanted (or needed) some cultural uplift.

No, the reason was: By the 1990s, the last of the old guard in Hollywood was dying off, replaced by the new guard, the Baby Boomers. As we know, it’s not enough for Boomers to control everything while making a shitload of money. No no, for them everything has to be deep and meaningful. They thought of themselves as artistes, not entertainers, so they had to put out a bunch of highbrow stuff, and we had to watch it. This is the sole reason goofy-looking Kenneth Branagh and his horse-faced wife (at the time) were a big cultural force. They made Shakespeare sexy, by which I mean, they allowed the studio heads to think of themselves as the arbiters of culture, not the carny trash they were and are. That some decent movies got made because of it, is entirely incidental.**

*Last summer, during the worst of lockdown mania, I introduced my little nephews to Bugs Bunny. The real ones, from the 40s and 50s, not the crap they put out ten, twenty years ago. I am an educated man by modern standards, but a lot of that stuff flew over my head … and they used to show these in front of popular movies, on military bases, etc.! There’s the classic Wagner one, of course — kill da wabbit!! — but another one involves The Barber of Seville, which I haven’t seen performed and had to look up. Even the “throwaway” music was classical — they could assume, in other words, that your average workaday guy or GI had a fairly large repertoire of classical pieces in his head, enough to recognize bits from Strauss, Chopin, Schumann, etc.

**I do kinda regret bashing Sir Kenneth, as wiki tells me he now is. I enjoyed Hamlet (again, despite the annoying cameos), and some of his other work was pretty entertaining, even, in a limited way, visionary — a quirky little picture like Dead Again didn’t do much in 1991, but it would clean up now (a PoMo costume drama!). I’m one of the few people who liked Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which again despite terrible casting (Robert De Niro? Seriously?) was loads of fun. Shelley’s novel as written is ludicrous, therefore unfilmable, but Branagh admirably captured the spirit of it. It’s as Goth as can be, in the original sense of “Gothic”. Wonderful stuff.

June 12, 2021

June 11, 2021

Latin and Greek are the next sacrifices to the great god Antiracism

In the latest edition of It Bears Mentioning, John McWhorter considers the Princeton University classics department decision to get rid of the requirement for students to read classic texts in the original languages:

“USA – New Jersey – Princeton” by Harshil.Shah is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

I have written recently about the Princeton classics department’s decision to eliminate the requirement that students engaging closely with Latin and Greek texts be able to … read them in Latin and Greek. The new idea is that the department will attract more majors by opening up to ideas from students who may be full of beans but just not inclined to tackle complex, ancient languages. And sub rosa, the idea is clearly – as we can see from words in the official statement like underrepresented, perspectives, and experiences – that of especial interest will be black students, especially in light of today’s racial reckoning which the department openly acknowledges was the primary spur for this change.

My disappointment with this decision is because it is part of a tradition of arguments that we do black people a favor by exempting them from certain kinds of faceless, put-up-or-shut-up challenges to entry. Back in the aughts, the classic example was brilliant, fierce black lawyers confidently arguing that because black firefighter applicants don’t do as well on the entrance exams required for the job, the exams are racist and should be eliminated. More recently there has been the idea that if black kids are rare at top-ranked public schools in New York City like Stuyvesant because few excel on the standardized test one must ace to be admitted, then the solution is to eliminate the test as “racist”. The Princeton decision is a variation: to get black kids into classics, it’s supposedly immoral to expect them to master the intricacies of Latin and Greek, languages which I suppose we can see as foreign, “white” to them as well. Rather, they must be admitted in shining expectation that their class comments will be bracingly “diverse” in good old English.

My Atlantic colleague Graeme Wood is more sanguine about the Princeton decision. He argues sagely that a certain kind of student happens to enjoy working their way through languages like Latin as a kind of puzzle (I openly admit being that type), but that there are others who don’t go in for that particular task and yet are itching and well-equipped to engage and analyze classical texts regardless. Graeme notes that we do not consider it an educational tragedy that specialists in English history are not required to be able to read Old English. (Although I wonder if this analogy would hold if the idea were someone specializing in England of the first millennium, where all of the relevant linguistic matter was in Old English [and Latin].)

I can go with him here to an extent. On the one hand, as I have argued here, to engage work only in translation is, of course, to lose a lot. Yet, in making that argument here, I was referring to my own reading War and Peace in English, as I myself was not inclined to hack through it in Russian (although my being black was not the reason for this disinclination [couldn’t help it!]). The question is how important we consider that loss to be.

Having no facility in languages myself, I’m more sympathetic to the students’ viewpoint than I might otherwise be, but depending on someone else’s translation of the text being studied has unexpected risks, as Sarah Hoyt explained from her own translation studies:

The discussion […] reminded me of when I was sixteen and embarked on a class called “Techniques of Translation”.

Although I had studied French and English and German, the translations I’d done so far were of the “I took the pen of my neighbor” variety. I thought the class would teach me to smooth out the sentence to “I took my neighbor’s pen” and that would be that.

I was wrong. Oh, it taught that also, but that was a minor portion of it. The class mostly hinged on the moral, ethical and — most of all — professional dilemmas of being a translator. I know any number of you are translators, formal or informal, but any number of you are also not. So, for the ones who are not, let me break the news with my usual gentleness:

There is no such thing as translation.

The French have a proverb “to translate is to betray a little” — or at least that’s the closest meaning in English. It’s fairly close to the true meaning, but slightly askew, of course. Every language is slightly askew to other languages.

The idea that there exists in every language a word that is exactly the equivalent of other languages is sort of like assuming that aliens will — of course — live in houses, go to school, ride buses, understand Rebecca Black’s “Friday”. [This was originally written in 2011.]

Language is how we organize our thoughts, and each word, no matter how simple, carries with it the cultural freight and experience of the specific language. Oh, “mother” will generally mean “the one who gave birth to” — except for some tribal, insular cultures where it might mean “the one who calls me by her name” or “my father’s principal wife” — but the “feel” behind it will be different, depending on the images associated with “mother” in the culture.

So, when you translate, you’re actually performing a function as a bridge. Translation is not the straightforward affair it seems to be but a dialogue between the original language and the language you translate into. If you’re lucky, you meet halfway. Sometimes that’s not possible, and you feel really guilty about “lying” to the people receiving the translation. When on top of language you need to integrate different cultures and living systems (which you do when translating anything even an ad) you feel even more guilty, because you’re going to betray, no matter how much you try. At one point, a while back, I had my dad on one phone, my husband on the other, and I was doing rapid-fire translation about a relatively straight forward matter. And even that caused me pangs in conscience, because my dad simply doesn’t understand how things are done here. I had to approach his experience and explain our experience in a way he wouldn’t think I was insane or explaining badly. That meant a thousand minor lies.

May 24, 2021

“The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared”

Sean Gabb discusses some outrageous elements of the ongoing cultural revolution against freedom of speech in Britain, the United States and many other western nations:

David Hume Tower at the University of Edinburgh (listed building number 50189).

Photo by Enric via Wikimedia Commons.

If I am a self-employed plumber or electrician, I can speak my mind and laugh at the complaints. If, like the great majority in this country, I am a salaried employee — whether in the state or private sectors is unimportant: the pressures to conformity are the same in both sectors — I must be careful what I say. I am scared of the sack. I am scared of sudden redundancy. I am scared of missing out on promotions. I am scared of generally unfair treatment because of my opinions. I therefore hide my opinions. The Peter Tatchells among us then look round complacently, telling themselves and each other that silence equals agreement, and that the few squeaks of opposition are from “disreputable extremists.”

This explains the present unbalanced debates over slavery and colonialism. Take these examples:

- First, in September 2020, the David Hume Tower at Edinburgh University was “denamed”. Someone had bothered to read the 1748 essay “Of National Characters”, and found in one of its footnotes an unfashionable statement about race. It was at once set aside that Hume was a philosopher of at least considerable note. More important was the “non-overt disrespect, offence, and racism that Black students have to go through at the University of Edinburgh”.

- Second, the Music Department at Oxford is presently worried that its curriculum “structurally centres white European music”, and that this causes “students of colour great distress”. It therefore wants to change its focus from the European classical tradition to things like “Artists Demanding Trump Stop Using Their Songs”. It also wants to discourage students from studying musical notation, as this is a “colonialist representational system”.

I could give a third illustration, and a fourth. I could fill a pamphlet with more. Some would be more alarming, though few less absurd. But these two can stand well enough for all the others. What makes these debates so irritating is that they are not debates. One side can put its case just as it pleases. The other is reduced to accepting all the main charges and begging for mitigation: “What Hume said was evil and unpardonable — but he was important for other things.” Or: “I feel your pain, but Mozart owned no slaves, and everyone knows that Beethoven was really black.” Because it has been so humbly begged, full mitigation will, in both cases, be granted. Hume will continue to be studied in the universities. Music students at Oxford will continue to use the standard notation and to analyse the usual classics. But preventing these things was never part of the agenda. The agenda was and is to transform what were honoured or unquestioned parts of our civilisation into things useful but more or less suspect, things subject to a toleration that may be varied or withdrawn at any time without notice.

It should be plain that we are, in both England and America, living through a revolution. This is not a normal revolution as these things are considered. Unlike in France or Russia, there has been no overthrow of an established order, no burst of state violence, no establishment after that of an overtly new order. There are no secret police. There are no labour camps. No one is beaten to death in a police cell. All the same, we are living through a revolution. It is a revolution that has involved the gradual capture of education, the media, the administration, the charities and the more permeable religious institutions, and the recent aligning of the larger or more glamorous business concerns. I see no point in discussing its ultimate objects. I am not sure if these are wholly agreed. But its provisional object is the destruction of our traditional identity, and of our liberty so far as this stands in the way of that provisional object.

These two elements of the provisional object are equally important. Our civilisation is being pulled apart because doing so strips away the mass of associations that, left in place, might hold up the more alarming parts of the transformation. Opposition is so feeble not only because that is all that will be tolerated: feeble opposition is all that can be tolerated. This is a revolution in which opponents are not murdered, but only scared into silence. They are scared into silence chiefly by fear of destroyed or blighted careers. The revolution will be defeated when people stop being scared. Then, there will be vicious and unrelenting public mockery, and commercial boycotts, and shareholder rebellions, and lost elections, and the general feeling of solidarity and impunity still sometimes found in a football stadium.

QotD: The internet is rewiring our brains

… there’s a reason 99.998% of the Internet is porn, and that reason is: The Internet, itself, has rewired our brains.

Yeah, I’m a history guy, not a biologist, and no, I can’t show you the specific spots on the fMRI that prove it, but look, you can test this yourself. Ever been around kids? It’s easiest to see in the early grades, so go to a daycare or afterschool program. Trust me, you can pick out right away, with 100% accuracy, the kids who spend more than 3 hours a day at daycare. This is not a knock on daycare providers, lots of whom are good, dedicated people doing hard work. Rather, it’s a knock on the situation, because if a kid’s in daycare that long, it means the parents both work long-hour, high-stress jobs. How do you think the kid’s home life is, under those conditions?

You know as well as I do that when the kid gets home from day care, he gets plunked in front of a tv, a video game, an iPad, a smartphone, some kind of glowing box. That’s what’s rewiring their brains. That’s not “ADHD,” which doesn’t really exist. “ADHD” is a cope, a bit of shorthand, to describe what’s actually going on, which is: These kids’ heads have been rewired. They need constant stimulation. Everything needs to be in five-minute chunks for them, because they’ve never known anything different. Asking them to sit down and pay attention for any length of time – say, in a 60 minute lecture, like our old Prussian (from the 18th century!) system requires – is like asking one of us to suddenly run a marathon, or bench press 300 lbs. It can’t be done; we don’t have the equipment.

Severian, “Bio-Marxism Grab Bag”, Founding Questions, 2021-01-21.

May 21, 2021

May 13, 2021

Canada’s (subdued-but-real) class system

In The Line, Howard Anglin offers some observations on how Canada’s class system developed and how it can be very roughly delineated:

This comfortably flat image of our social hierarchy, however, belies a more complicated series of gradations that, while clearly marked, are rarely observed and almost never described accurately. Peter C. Newman mapped some of the terrain in his three volumes on The Canadian Establishment, but his account was already dated when he began it in 1975 and it was a work of history rather than social commentary by the time he finished in 1998. [Line editor Jen] Gerson’s own description of the Canadian class system explains why it can be hard for outsiders, and even insiders, to see it: “[W]e manage the cognitive dissonance presented by the haves and have-nots of housing,” she says, “by requiring our rich people to keep quiet. They should wear clothes that are well-cut and well-designed, but not flash. Buy the multi-millionaires car, but paint it in a sedate hue.”

Social sorting is intrinsic to human nature, perhaps even necessary — as the Bard has Ulysses remind us: “Take but degree away … and, hark, what discord follows!” — and it’s here in Canada too, if you look for it. Like the United States, Canadians early on replaced a class system based on titles with one based on the more easily-acquired currency of, well, currency. And, as in America, this immediately created a new opportunity for class to subtly reassert itself.

I used to joke that the only meaningful class division in Canada is whether you use “summer” as a noun or as a verb; lately I’ve developed the Starbucks test. In this analogy, Starbucks is Canada’s middle class, with Tim Hortons and fast food franchise coffee below, and specialty cafes and boutique chains (Matchstick, Phil & Sebastian, Bridgehead) above.

Unlike the crude measure of income, coffee choice better replicates a traditional class system because it carries an implicit sense of social solidarity, cultural assumptions and biases. During the days of the Harper government, Tim Hortons became a symbol to a certain sort of conservative as iconic as the Greek fisherman’s cap is to aging Marxists. The Maple Leaf red cup represented the honest values of rural and suburban working families, in contrast to the globalist elites with their overpriced green Starbucks. Starbucks was sipped at dog parks and served in board rooms; Tim Hortons got the job done on a cold winter morning: it was Don Cherry in a mug.

The Starbucks test is a silly heuristic, but it reveals something about the complex nature of class: an aristocrat may be penniless, and a billionaire may love his Tims. It also puts the middle class back in its traditional place as the uneasy middle-child of the social order.

In the old British system, there was pride in being working class. There was a bond of mutual support that grew out of the shared experience of hard labour and was reinforced by institutions like working men’s clubs, the British Legion, and the trade union movement. The middle-class striver with his airs and pretensions, his flash new car and his evolving accent, was a figure of general mockery, even more to the working men he left behind than to the upper classes he aspired to join. Class was about more than money; it was an identity. And there was nothing that gave you away as middle class more than worrying about being middle class — an anxiety exploited by Nancy Mitford in her tongue-in-cheek guide to “U” and “Non-U” language and behaviour. The Starbucks test reveals something similar, something more reflective of Canada’s reality than the Liberal vision of one big happy middle-class family.

Tim Worstall explained that the British middle class is still despised by the upper class and hated by the lower class. Not a model for encouraging aspirational working class folks to “move up”.

May 12, 2021

Looking at a highly influential document among progressive groups

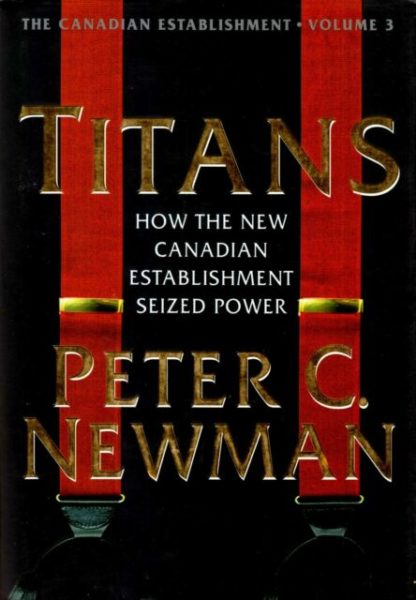

Matthew Yglesias on Tema Okun’s “The Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture” and its role in furthering progressive emotions over what they consider to be the most racist society in human history (that is, the modern west but especially the United States):

Debating abstractions is difficult and frustrating, and the discourse about “wokeness” and “cancel culture” has become a snakepit of semantic debates, bad-faith actors, and people of goodwill talking past each other.

So I want to talk instead about one specific document, not because I think it’s the most important document in the world, but because I don’t really see anyone who I read and respect talking about it even though I’ve seen it arise multiple times in real life.

I’m talking about “The Characteristics of White Supremacy Culture” by Tema Okun, which I first heard of this year from the leader of a progressive nonprofit group whose mission I strongly support. He told me that some people on the staff had started wielding this document in internal disputes and it was causing big headaches. Once I had that on my radar, I heard about it from a couple of other nonprofit workers. And I saw it come up at the Parent Teacher Association for my kid’s school.

It’s an excerpt from a longer book called Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups that was developed as a tool for Okun’s consulting and training gigs.

But today, even though it’s not what I would call a particularly intellectually influential work in highbrow circles — even ones that are very “woke” or left-wing — it does seem to be incredibly widely circulated. You see it everywhere from the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence to the Sierra Club of Wisconsin to an organization of West Coast Quakers.

Which is to say it’s sloshing around quite broadly in progressive circles even though I’ve never heard a major writer, scholar, or political leader praise or recommend it. And to put it bluntly, it’s really dumb. In my more conspiratorial moments, I wonder if it’s not a psyop devised by some modern-day version of COINTELPRO to try to destroy progressive politics in the United States by making it impossible to run effective organizations. Even if not, I think the document is worth discussing on its own terms because it is broadly influential enough that if everyone actually agrees with me that it’s bad, we should stop citing it and object when other people do. And alternatively, if there are people who think it’s good, it would be nice to hear them say so, and then we could have a specific argument about that. But while I don’t think this document is exactly typical, I do think it’s emblematic of some broader, unfortunate cultural trends.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.

May 4, 2021

Preparing for the worst (and hoping it won’t happen)

I’m generally optimistic about the big picture in any given situation no matter how pessimistic I’m inclined to be on smaller matters and individual details. For this reason, I try not to think too much on just how bad things might get if too many current cultural trends continue as they are. Sarah Hoyt, on the other hand, has some suggestions for getting past any potential social upheavals we may face in the very near future:

If you’re in a major city and I like you, I beg you, with tears in my eyes to get out as soon as you can (and yes, we’re working on it.) Some neighborhoods and places will be safe-ish, but in the US the brunt of the horrific will be in big cities, because that’s what the left thinks MATTERS and where they’ll concentrate their effort.

Forgive me for corporate speak from the nineties, but in this case it applies: their paradigm is broken and they can’t see it because they’ve done everything possible to insulate themselves from input coming from outside the paradigm.

When this happens and the people of the dead paradigm still have some power, the result is kind of like when you fill a container with gasoline, then drop a match in. It’s best to be in the places they think don’t matter.

Other than that: well, you don’t know how interconnected the world supply chains are, until they break. These last two years have been a lesson and no mistake. When I say we’ll unfuck ourselves relatively fast, it doesn’t mean we’ll reverse disastrous globalization in an eye blink. We won’t.

Try to have the things you think you’ll need for five-ten years. That includes newish computers (the silicon crisis is real) perhaps more expensive than you’re used to buying, and raw materials for what you’ll need, from fabric to … I don’t know. Probably not clay. But now might be a bad time to downsize and get rid of that “for company” dish set, depending on your rate of breakage of the everyday one. Lay by paper, too. If we start getting electricity brownouts and blackouts, having stuff you want to keep printed might help.

Food. I don’t need to say it. I think I have maybe enough for a year and a half, though at the end our diet would be mighty strange. But we’re already hearing screams of food supply failure. (I want to get us moved, and start laying in more food. The delays and set backs are driving me nuts.)

And what about the stupid laws proscribing wrong thinkers? For now? Nothing. If you’re hidden and submerged stay that way. Look at it this way: if the people who hid Jews in their attics had come out early to defend them, they too would be in the camps and unable to help. We’re already past the point where “a brave stand” will help. The left knows they’re losing. They can’t understand why, but they know they’re losing, and they’re angry and murderous because of it. And they won’t let go, until it all explodes in their faces. So if you are hidden, stay thus, and get ready to hide people in your metaphorical attic. Because those like me who are exposed, if they have a good bit of luck, just might manage to make it there.

Just prepare, prepare as hard as you can.

You’ll be blindsided. We all will be. Seriously. Books that go through this lie. It’s always more complex and more difficult than you can imagine, and you will be caught off guard.

If you’re lucky, the things you’re caught in won’t kill you.

If we’re all lucky we’ll come out the other side alive and well, most of us. Which is good, because we’ll be needed if we want future generations to grow up under a constitutional republic.

The rest of the world? Foggedaboutit. Not a chance. They’re going to try to crawl back to pre-English enlightenment. Some areas will manage it, too.

For us? I don’t know. There is a chance. Honestly. A chance is all we can ask for.

So, let’s survive and be ready to push the odds. Because the destruction will be everywhere. But the re-building must begin in America.

March 25, 2021

Modern Artists: The Original Shitposters! | B2W: ZEITGEIST! I E.14 – Winter 1922

TimeGhost History

Published 24 Mar 2021The interwar era has seen an explosion of art movements all vying to offer the most revolutionary response to modern society. The competition is intense and, as we shall see, often spills over into open conflict.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Edited by: Michał Zbojna

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/TheYankeeCol…Sources:

Some images from the Library of CongressSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

“Epic Adventure Theme 3” – Håkan Eriksson

“Crimp” – Hysics

“Substage” – Jay Varton

“Appeased Soundscape 01” – August Wilhelmsson

“Stranger Days” – Alexandra Woodward

“Superior” – Silver Maple

“Rememberance” – Fabien Tell

“Ghost Dungeons” – Ethan Sloan

“Ancient Discoveries” – Gabriel LewisArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago (edited)

The original idea for this episode came from me (Francis here, hello) stumbling across a passing reference to the 1922 trial of André Breton buried deep in a Wikipedia article. It led me down a huge rabbit hole on the history of the chaotic artists milling around in Paris, New York, Zurich, and beyond.Considering that it also takes place in the same season as the publication of Ulysses, the release of Nosferatu, the birth of Brazillian Modernism, and more, I realized that it was the perfect opportunity to dedicate an entire episode to the weird and wonderful artistic movements of the modern era. If this kind is new to you then consider this episode your introduction to the topic. Indy talks about the Cubist revolution, then Dadaism, Expressionism, and more.

In case all that seems a bit too niche for your liking then look at it this way: if you want to understand how people processed the horrors of the Great War, the rise of mass production, and modern geopolitical machinations, then diving into the art of the time is a great place to start.

Watch the video to find out why.

March 24, 2021

QotD: Politicians

The fact that so many successful politicians are such shameless liars is not only a reflection on them, it is also a reflection on us. When the people want the impossible, only liars can satisfy.

Thomas Sowell, “Big Lies in Politics” (syndicated column), 2012-05-22. (via Terry Teachout)

March 21, 2021

The two Britains, gastronomically speaking

Theodore Dalrymple on the British diet (at least before the neverending lockdowns):

“The Joy of Cookbooks” by shoutabyss is licensed under CC BY 2.0

As in many other things, the population has divided into two: those with increasingly refined tastes in gastronomy, and those who eat mainly junk and takeaway food for the quickest but also crudest possible gratification.

Gastronomy often seems the only aesthetic sphere in which the modern British display any real interest. Their dress, their music, their art (or at least such as gains any publicity), their literature, and of course their architecture, are hideously ugly, even militantly so, but a Michelin-starred restaurant receives their adulation — or did in the now-distant days when restaurants were open.

But the modern interest in food is not the same as a mass market for fish, which has, alas, mainly to be cooked, and the fact is that the British are, grosso modo, too lazy and ignorant to cook properly. Many millions of them would be horrified by the sight of a whole fish, or even any part of a raw fish: they don’t want to eat anything that hasn’t been through a complex industrial process, had chemicals and preservatives added to it, and cannot be just stuck in a microwave for a few minutes before consumption in front of the television. Besides, they wouldn’t know what to do with a fish, let alone a crustacean.

It is said that about a fifth of British children do not eat a meal with another member of their household (family would, perhaps, be a misleading term) more than once a fortnight, turning meals into asocial and even furtive occasions. Many households do not have a dining table, and in my visiting days as a doctor I discovered that the microwave is often a household’s entire batterie de cuisine.

This slovenly and asocial approach to eating — evident in the detritus left behind in British streets as people eat wherever they happen to be, in their cars, walking along, in trains and buses, in fact anywhere but a dining room and with others — is not the consequence of poverty, but of a degraded style of life.

Many years ago I noticed that shops in poor areas where there were many immigrants of Indian origin had enormous piles of a vast array of vegetables so cheap that the problem was carrying them home rather than their cost. I would see Indian housewives selecting their purchases with care and attention: the quality and not just the price mattered to them. Uncompelled by economic necessity to shop there, I would nevertheless do so; but I never saw poor whites doing so. The problem with all those vegetables was that they required cooking, preferably with skill, which very few poor whites, as against poor Indians, had. And this is a cultural problem, if the taste for and consumption of a diet of junk food (what the French more vividly call malbouffe) is a problem.

The Indians are fat, with bad health consequences, from eating too much good food; the native British, with bad health consequences, from eating too much bad food. The prevalence of obesity in Britain, greater than in most other European countries, is possibly one of the reasons that its death rate from COVID-19 is so high, among the highest if not actually the highest. And this obesity is immediately obvious on arrival in Britain from any European country.

March 15, 2021

QotD: The “Greatest Generation”‘s expectations of the Boomers

I’ve never bought into the “greatest generation” stuff. I saw it as a Jungian appeasement of the boomers towards their aging fathers whom they’d “sacrificed” in more ways than one. I’m at heart — or at back brain — very Roman. To explain why would take more uncomfortable biographical revelations than I have time for, including “because that’s what I was brought up to be.”

I get this dance very well. First comes the sacrifice, then the deification.

Did the World War II generation rise to the challenge? Yes, they did. But in a way they’d been brought up for it: a generation grown to continue Europe’s long war, because the previous generation had been eaten in the fields of WWI.

And can anyone blame the veterans, coming back from yet another European abattoir for wanting to put an end to the cycle?

Obviously something had gone wrong in Western civilization and it needed to be stopped. The next generation were going to be a brand new beginning. They were going to make it all better.

Did I mention the serpent in the garden? You can’t make the garden without the serpent.

A lot of the crazy of the sixties, and the unmaking of society was what the boomers were explicitly raised to do. A lot of the poison in our cultural waters was the rebellion of the veterans of WWII. An understandable rebellion, but one that threw the baby out with the bath water nonetheless.

However, even the boomers who weren’t raised on utopian ideals, who weren’t told the world was theirs to remake, even the ones who didn’t protest (or fought in) the war, even the ones who were and are decent human beings were raised with the idea that it was theirs to change Western Civ to be more … humane. Or at least not to self-destruct in battlefields.

This created an ur-programming, a back brain thing. Even responsible boomers who cut their hair, got jobs and raised families had the idea that they were supposed to transform everything.

Sarah Hoyt, “Business From The Wrong End”, According to Hoyt, 2018-09-27.