What are affairs like for poor spartiates?

First, we need to reiterate that a “poor” spartiate was still quite well off compared to the average citizen in many Greek poleis – we talk about “poor” spartiates the same way we talk about the “poor” gentry in a Jane Austen novel. None of them are actually poor in an absolute sense, they are only poor in the sense that they are the poorest of the rich, clinging to the bottom rung of the upper class.

Nevertheless, we should talk about them, because the consequences of falling off of that bottom rung of the economic ladder in Sparta were extremely severe because of the closed nature of the spartiate system. Here is the rub: membership in a syssition was a requirement of spartiate status, so failure to be a member in a syssition – either because of failure in the agoge or because a spartiate could no longer keep up the required mess contributions – that meant not being a spartiate anymore.

The term we have for ex-spartiates is hypomeiones (literally “the inferiors”), which seems to have been an informal term covering a range of individuals who were (or whose family were) spartiates, but had ceased to be so. The hypomeiones were, by all accounts, mostly despised by the spartiates and the hatred seems to have been mutual (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6). Interestingly in that passage there – Xenophon’s Hellenica 3.3.6 – he lists the Spartan underclasses in what appears to be rising order of status – first the helots (at the bottom), then the neodamodes (freed helots, one step up), then the hypomeiones, and then finally the perioikoi. The implication is that falling off of the bottom of the spartiate class due to cowardice, failure – or just poverty – meant falling below the largest group of free non-citizens, the perioikoi.

Herodotus gives some sense of the treatment of men who failed at being spartiates when he details the two survivors of Thermopylae – Aristodemus and Pantites. Both had been absent from the battle under orders – Pantites had been sent carrying a message and Aristodemus had suffered an infection. When they returned to Sparta, both were ostracized by the spartiates for failing to have died – Pantites hanged himself (Hdt. 7.232) while Aristodemus was held to have “redeemed” himself with a suicidal charge at Plataea which cost his life (Hdt. 7.231). And as a side note: Aristodemus is the model for 300’s narrator, Dilios – so when you see him in the movie, remember: the Spartan system drove these men to pointless suicide because they followed an order.

But my main point here is that falling out of the spartiate system meant social death. Remember that the spartiates are a closed class – failing at being a spartiate because your kleros is too poor to maintain the mess contribution means losing citizen status; it means your children cannot attend the agoge or become spartiates themselves. It means you, your wife, your entire family forever are shamed, their status as full members of society forever revoked and your social orbit collapses on you, since you are cut off from the very ties that bind you to your friends. No wonder Pantites preferred to hang himself.

In essence then, the core of the problem here is not that these poor spartiates were poor in any absolute sense – they weren’t. It was that the difference between being rich and being merely affluent in Sparta was a social abyss completely unlike any other Greek state. And that abyss was completely one way. As we’ll see – there was no way back.

Our sources are, unfortunately, profoundly uninterested in answering some crucial questions about the hypomeiones: did they keep their kleroi? What happened to the status of their children? What happened to the status of the women in their families? We can say one thing: it is clear that there was no “on-ramp” for hypomeiones to get back into the spartiate system. This is made quite clear, if by nothing else, by the collapsing number of spartiates (we’ll get to it), but also at the inability of extremely successful non-Spartan citizens – men like Gylippus and Lysander – to ever join the homoioi. Once a spartiate was a hypomeiones, they appear to have been so forever – along with any descendants they may have had. Once out, out for good.

All of that loops back to the impact of the great earthquake in 464. It is likely there were always spartiates who – because their kleroi were just a bit poorer, or were hit a bit harder by helot resistance, or for whatever reason – clung to the bottom of the spartiate system financially, struggling to make the contributions to the common mess. When the earthquake hit, the death of so many helots – on whom they relied for their economic basis – combined with the overall disruption seems to have pushed many of these men beyond the point where they could sustain themselves. Unlike in a normal Greek polis, they could not just take up some productive work to survive and continue as citizens, because that was forbidden to the spartiates, so they collapsed out of the class entirely.

(As an aside – the fact that wealthy spartiates, as mentioned, seemed to prefer each other’s company over the rest probably also meant that the social safety-net of the poor spartiates likely consisted of other poor spartiates. Perhaps in normal circumstances they remained stable by relying on each other (you help me in my bad year, I help you in yours – this is very common survival behavior in subsistence agriculture societies), but the earthquake – by hitting them all at once – may well have caused a downward spiral, as each spartiate who fell out of the system made the remainder more vulnerable, culminating in entire social groups falling out.)

As I said, our sources are uninterested in poor spartiates, so we can only imagine what it must have felt like, clinging desperately to the bottom of that social system, knowing how deep the hole was beneath you. One imagines the mounting despair of the spartiate wife whose job it is to manage the household trying to scrounge up the mess contributions out of an ever-shrinking pool of labor and produce, the increasing despair of her husband who because of the laws cannot do anything but watch as his household slides into oblivion. We cannot know for certain, but it certainly doesn’t seem like a particularly happy existence.

As for those who did fall out of the system we do not need to imagine because Xenophon – in a rare moment of candor – leaves us in no doubt what they felt. He puts it this way: “they [the leaders of a conspiracy against the spartiates] knew the secret of all of the others – the helots, the neodamodes, the hypomeiones, the perioikoi – for whenever mention was made of the spartiates among these men, not one of them could hide that he would gladly eat them raw” (Xen. Hell. 3.3.6; emphasis mine).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part IV: Spartan Wealth”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-08-29.

August 23, 2022

QotD: The fate of suddenly poor Spartiates

August 21, 2022

The pandemic lockdowns heralded the “worldwide end of the Nuremburg code”

At Samizdata, Perry de Havilland considers how British culture has been impacted by many of the worst notions coming out of American culture in the last few years:

… support for Brexit, by no means confined to the lumpenproletariat of Guardian reader’s imagination, might not indicate what purveyors of the high status opinion fondly imagine. The conflation of Brexit with the “Trump phenomenon” was always overblown, given the deep social and structural differences between UK and USA. Yes, we are influenced by America, but we are not the same in oh so many ways.

But western civilisation, not just Britain, is undeniably going through a very strange phase. The insane and demonstrably pointless covid lockdowns seem to have had a pressure cooker effect, with every -ism being dialled up several notches. The mainstreaming of transsexuality, a largely harmless hobby until a lunatic fringe grabbed hold of it, indicates the world is not running in well-oiled grooves. An inability to define “what is a woman?”, by sages and politicians who nevertheless expect to be treated as serious people, would have seemed implausible just a few years ago.

But the covid lockdowns, that is the “biggie”: an egregious abridgement of liberty & common sense that placed the global economy into repeated bouts of cardiac arrest. The worldwide end of the Nuremburg code.

The lockdowns were an even more polarising issue that Brexit or Trump or indeed anything else. Why? Because there was no opt-out, you could not just go to work, or visit granny, no ability to ignore the whole thing and just head down the pub or retire for a macha latte in some café. The effects of that will be enduring. That was the issue that taught a lot of people to fear what other people believe to be true, and people always hate what they fear.

Now just wait to see what happens when the green lunacy that stopped investment in reliable power supply and new reservoirs means we start running out of power and water. I suspect that will be what makes the cork finally blow off.

August 19, 2022

“This is her advice: Get Married and Make Sure You Stay Married”

Elizabeth Nickson was a feminist entrepreneur (although I’m sure she would not have used that word to describe herself) in her early 20s, earning money to support herself by pushing feminist ideology through theatrical performance and running consciousness raising sessions. It was, as she says, “fashionable”. She now realizes that the changes to sexual belief and behaviour led directly to the modern “hook-up” culture young people now have to navigate to find relationships:

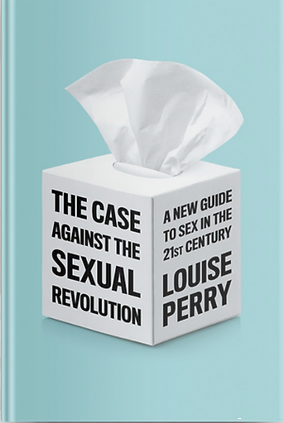

A new book, the Case Against Sexual Revolution, A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century, written by Louise Perry, a young writer for the New Statesman is published at the end of this month. Perry volunteers in rape centers, and works for the campaign group We Can’t Consent To This, which documents cases in which UK women have been killed and defendants have claimed in court that they died as a result of ‘rough sex’.

This is her advice: Get Married and Make Sure You Stay Married.

Dramatically well-argued and sourced, Perry goes through every “innovation” in the sexual space and demonstrates without flinching, that all of it, all of it, privileges a particular subset of male, the sociosexual male – the kind that preferences quantity over quality – and not only that the worst kind of sociosexual male. The kind who like choking women, the rapists, abusers, serial womanizers, the pedophiles, the pimps, and the traffickers.

Decades later, says Perry, the mothers and grandmothers of 2nd and 3rd stage feminism have created hook-up culture as the near exclusive method of finding a mate. She details the unassailable fact that women, by their very nature, by their evolutionary history, and their specific biology are victimized in every move of hook-up culture, which ruthlessly uses their femininity, their gentleness, kindness, and agreeableness against them. It coarsens men, inflames their worst natures and has turned the netherworld of the sexual marketplace into a vicious free-for-all, a Darwinian thrash-hunt of the most vulnerable.

Everyone is hurt by it. Without exception.

I live in a place socially advanced, jokingly known as the end of the hippie trail. It is prosperous because it is one of the most beautiful places in the world. But, because it is environmentally advanced, our population is aging. The young and busy cannot start businesses or families here, because the environmental regulation is so strict, they cannot afford it. The human wreckage of the sexual revolution, therefore, is on full display. The streets and markets are littered with broken older men and women, long divorced or separated, the women especially living on crumbs, alone and destined to die alone, many without family. Hey, but their 20s and 30s were free. They got to have sex with dozens, if not hundreds of gorgeous men or women. And they used all the drugs.

If you look hard enough, you will see the same people drifting along the margins of every city and town. Break sexual norms, you break the family, and then you break the culture. What is left is pitiable.

Perry makes the point that I have tried to make hundreds of times in the past 20 years. So many of the political aims of upper-middle-class work for them, but for no one else. They are luxury beliefs. Upper-middle-class mothers do not send their gorgeous teens away to college now without very stern warnings about what might happen to them. Without a full delineating of the horrors that attend hooking up. But the less advantaged, those who swallow the propaganda of the culture do not.

August 8, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 6 – The Birth of England

seangabb

Published 4 Aug 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western Provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 5, 2022

“… what explains the growing enthusiasm for ‘Drag Queen Story Hour'”?

In UnHerd, Andrew Doyle considers the deep weirdness of how not just “Drag Queen Story Hour” but all things drag are being pushed on children at any cost:

“One thing that drag queens don’t get on FLICKR is tips” by kennethkonica is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0 .

One Easter Sunday, many years ago, some friends and I attended a showcase of performances in a network of dank subterranean vaults. The event was self-consciously avant-garde, and many of the artists were drag queens who were exploring the more subversive aspects of their craft. This involved a great deal of screaming, bloodletting and carnal depravity. At one point I wandered into a chamber in which two naked performers were engaged in full penetrative sex. Around them a cluster of middle-class hipsters had formed, pensively observing them as though they were connoisseurs contemplating a Henry Moore.

These days we are accustomed to a somewhat tamed version of drag. But the best performers have always pushed the limits of acceptability: I once appeared at a comedy night at the Edinburgh fringe hosted by a drag queen whose interaction with the punters was not so much waspish as downright libellous. At another, I remember a drag artist smoking liberally during the performance, blowing smoke at a pregnant woman on the front row and saying “I hope you have a miscarriage”. It was a far cry from RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Traditional drag is clearly meant for adults. So what explains the growing enthusiasm for “Drag Queen Story Hour”, in which drag queens visit schools, libraries and other council venues to read to young children? For whatever reason, this bizarre subgenre has been championed by celebrities and politicians who wish to be seen as being on “the right side of history”. Last week the MP for Walthamstow, Stella Creasy, tweeted about taking her infant son to a show in which a drag queen called Greta Tude “put so much energy into story telling and entertaining local children”. Her colleague Nadia Whittome replied, describing the event as “so wholesome”.

But do fans of drag really want it to become “wholesome”? The appeal of drag shows is that they revel in sexual dissidence, as the American drag queen Kitty Demure has pointed out:

I have no idea why you want drag queens to read books to your children … Would you want a stripper or a porn star to influence your child? It makes no sense at all. A drag queen performs in a nightclub for adults. There is a lot of filth that goes on, a lot of sexual stuff that goes on, and backstage there’s a lot of nudity and sex and drugs. Okay? So I don’t think this is an avenue that you would want your child to explore.

The sexual element of drag is impossible to deny. Even the more tepid drag queens, whose repertoire extends no further than lip-synching to Donna Summer, tend to interlace their performances with suggestive gestures, provocative quips and the occasional slut-drop.

That’s not to say drag queens can’t adapt to a younger audience — they are actors after all. It’s perfectly possible for performers of Drag Queen Story Hour to read stories to children without all the eroticised preening and pouting we have come to expect from them. But why would any self-respecting artist want to do it? There is something deeply mystifying about drag queens who choose to anaesthetise their art form in order to regale infants with tales of teddy bears and picnics.

August 2, 2022

July 28, 2022

The History of American Chip Flavors

J.J. McCullough

Published 2 Apr 2022The story of chips is the story of America.

(more…)

July 27, 2022

July 25, 2022

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte, the Great Man’s Great Man

The point is, a culture can survive an incompetent elite for quite a while; it can’t survive a self-loathing one. This is because the Great Man theory of History, like everything in history, always comes back around. History is full of men whose society doesn’t acknowledge them as elite, but who know themselves to be such. Napoleon, for instance, and isn’t it odd that as much as both sides, Left and Right, seem to be convinced that some kind of Revolution is coming, you can scour all their writings in vain for one single mention of Bonaparte?

That’s because Napoleon was a Great Man, possibly the Great Man — a singularly talented genius, preternaturally lucky, whose very particular set of skills so perfectly matched the needs of the moment. There’s no “social” explanation for Napoleon, and that’s why nobody mentions him — the French Revolution ends with the Concert of Europe, and in between was mumble mumble something War and Peace. The hour really did call forth the man, in large part, I argue, because the Directory was full of men who were philosophically opposed to the very idea of elitism, and couldn’t bear to face the fact that they themselves were the elite.

Since our elite can’t produce able leaders of itself, it will be replaced by one that can. When our hour comes — and it is coming, far faster than we realize — what kind of man will it call forth?

Severian, “The Man of the Hour”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-05-22.

July 22, 2022

Sexual liberation to sexual revolution to … today’s sexual desert

Chris Bray thinks that the sexual revolution “missed a turn, somewhere out in the desert”:

The discussion of what we didn’t mean to do is becoming an interesting one:

After decades of sexual liberation — Mattachine, Stonewall, Loving v. Virginia, Griswold v. Connecticut, Second Wave feminism and the Sexual Revolution, Lawrence v. Texas, Obergefell v. Hodges, and whatever else I’m missing in there (and I’m not sure Roe belongs on the list, but maybe) — we somehow arrive at a moment in which we merge a sexualized display of childhood and a relentless media-driven commodification of sexuality with the very clear reality that nobody’s having any sex:

One of the most comprehensive sex studies to date — the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior — found evidence of declines in all types of partnered sexual activity in the U.S. Over the course of the study from 2009 to 2018, those surveyed reported declines in penile-vaginal intercourse, anal sex and partnered masturbation …

Over the last 22 years, Herbenick has co-authored several studies about our sexual activity. Her most recent research finds that all of us, regardless of age, are having less sex, with the most dramatic decline among teenagers.

At the start of the study in 2009, 79% of those ages 14 to 17, revealed they were not having sex. By 2018, that number rose to 89%.

Liberation stabbed pleasure in the heart; we emptied sex. Hypersexualization turns out to be desexualization. The unrelenting joylessness and death odor of contemporary sexual culture emerges from seventy years of growing openness and freedom. How?

There’s no way to fully cover a question of that scope in a single post — but I refer, as a start, to the earlier posts I wrote about the sexualization of childhood and the way Jim Jones used sex as a weapon. Breaking barriers and repressive anchors broke connections and reference points: Yes, some people were trapped in oppressive societal norms, and it’s not at all my view that all the sexual liberation in our past wasn’t really liberating. But we broke marriage to set people free, and whoops. Some people experienced bourgeois heteronormativity as a prison, and so set out to release everybody from their cages, which seem to have not been cages for a whole lot of people. Congratulations, we’ve freed you from being part of a family.

July 15, 2022

QotD: Modern and historical multiculturalism

For history’s rare multiracial and multiethnic republics, an “e pluribus unum” cohesion is essential. Each particular tribe must owe greater allegiance to the commonwealth than to those who superficially look or worship alike.

Yet over the last 20 years we have deprecated “unity” and championed “diversity”. Americans are being urged by popular culture, universities, schools and government to emphasize their innate differences rather than their common similarities.

Sometimes the strained effort turns comical. Some hyphenate or add accents or foreign pronunciations to their names. Others fabricate phony ethnic pedigrees in hopes of gaining an edge in job-seeking or admissions.

The common theme is to be anything other than just normal Americans for whom race, gender and ethnicity are incidental rather than essential to their character.

But unchecked tribalism historically leads to nihilism. Meritocracy is abandoned as bureaucrats select their own rather than the best-qualified. A Tower of Babel chaos ensues as the common language is replaced by myriad local tongues, in the fashion of fifth century imperial Rome. Class differences are subordinated to tribal animosities. Almost every contentious issue is distilled into racial or ethnic victims and victimizers.

History always offers guidance to the eventual end game when people are unwilling to give up their chauvinism. Vicious tribal war can break out as in contemporary Syria. The nation can fragment into ethnic enclaves as seen in the Balkans. Or factions can stake out regional no-go zones of power as we seen in Iraq and Libya.

In sum, the present identity-politics divisiveness is not a sustainable model for a multiracial nation, and it will soon reach its natural limits one way or another. On a number of fronts, if Americans do not address these growing crises, history will. And it won’t be pretty.

Victor Davis Hanson, “Things That Can’t Go on Forever Simply Don’t”, PJ Media, 2019-04-17.

July 1, 2022

Trust “the experts”

Chris Bray on the appalling track record of so many of our modern-day “experts”:

So the public health experts are baffled by the consistent failure of their predictive models, and the economic experts are baffled by the consistent failure of their predictive models. It’s like a chef who keeps trying to grill a steak, only to find that he’s burnt another lemon pie. “I SWEAR TO GOD I THOUGHT THIS ONE WAS A BEEF THING.”

These people aren’t stupid, but they’re stupid in practice because they show up to the game with the weight of what they know people in their position are supposed to say and think. Fashionable experts, in-group leaders in their status-compliant position in a field, aren’t reviewing the evidence — ever — but are instead reviewing a performative checklist dotted with social status land mines.

They’re on a team, so they say the team slogans.

[…]

If that’s how expertise works, we no longer have have any. We have actors who play the brow-furrowing expert role, but have no real job beyond intoning the message of the day. It says on this card that we recommend even more Covid vaccines for everyone. Let’s break for lunch!

But, mercifully, that’s not invariably how expertise works. And this is why politicians and trend-policing media figures are so completely baffled by experts like Robert Malone or Ryan Cole, or Geert Vanden Bossche or Clare Craig or Peter McCullough, experts who follow the evidence wherever it goes. Tone and social reception tells you a lot: Does an expert say things that aren’t comforting, that sound a little … not on the team? That person clears the first barrier, and you can start assessing the specifics of what they say. Look for journalists who are offended and triggered, and try to find the person who hurt their feelings. That person may turn out to be wrong, but he won’t turn out to be Paul Krugman wrong.

June 25, 2022

QotD: The Left’s long march through the institutions

Old-school Commies were consummate players of the long game. They knew they’d have to completely undermine bourgeois society before they could carry off The Revolution, so they did. Antonio Gramsci laid it all out theoretically, if you feel like slogging through that gunk, but the Commies had been doing it in practice for decades before that. Starting with the educational “reformers” surrounding John Dewey at the turn of the 20th century, they took over our grade schools. Then they took over the universities, working their way up from the community colleges (often Commie fronts from the get-go; there’s a reason the number of jucos nationwide went from 20 to 170 in just ten years, from 1909 to 1919).

Once they were in, they of course credentialized everything, such that the cultural-transmission professions — journalism, education, even art and music — suddenly required college training … and all the trainers were Reds. Ever wonder why you seemingly have to have a fucking Master’s Degree to get your lit-wank novel published? Seriously: read the author bio of any of the flavor-of-the-minute wunderkinder that get their painfully quirky dreck blurbed in the New York Times Review of Books — every blessed one of them has some kind of advanced degree in “creative writing”. All those graduate-level “creative writing” programs aren’t just make-work for otherwise unemployable Eng-Lit PhDs, in other words. They’re what the Union of Soviet Writers was in the USSR: The guarantors of politically-reliable content.

That’s the setup. Ready for the twist?

They won, but they don’t know it. Not only was the Revolution televised, it’s still being televised, 24 hours a day, on 587+ satellite cable channels and umpteen digital streaming services. Eugene V. Debs’s wettest wet dream couldn’t compare to Current Year America. The SJWs are like the Seekers, out there desperately trying to prepare the world for the UFOs … but the UFO already landed in their backyard, and they were too busy trying to save the world to see it.

That’s why widespread political violence is inevitable, and damn soon. Nancy Pelosi may be the nastiest evil old bitch to ever slime through the halls of Congress, but she’s not stupid. She’s just in an impossible situation. She’s the leader of an organization that didn’t manage its True Believers, and now she’s fucked either way. […]

That’s what the old-school Commies didn’t see coming. Those poor deluded fools really thought that “intellectual” was an adjective. The Russian word for the noun version is intelligentsia, and they gave the Soviet Union no end of trouble — Stalin had to send boxcars of them to Siberia fairly regularly to keep them in line. In the West, though, they really thought that you can have an “intellectual” steelworker, or dockhand, or farmer, and the like. They were counting on it, in fact — see “community colleges were all Red fronts”, above.

Instead, “intellectual” is the True Believer’s self-chosen job description. You can meet some fearsomely learned people in your day-to-day, but the only people you’ll ever meet who use the word “intellectual” without sneering are Media types and their panty-sniffers in the ivory tower. They’re extremely useful idiots, which is why none of Palsy Pelosi’s predecessors sent them to Siberia like they should’ve. And now it’s too late.

Severian, “If the UFO Actually Comes, Part II”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-09-26.

June 24, 2022

The Guardians of Free Speech

ReasonTV

Published 23 Jun 2022Because of the social media circus surrounding the Johnny Depp/Amber Heard defamation trial, it was easy to overlook one of the principal — yet least likely — actors in the courtroom drama: the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which ghostwrote and placed the 2018 Washington Post op-ed by Heard about surviving domestic abuse that was the basis of the trial.

——————-

It’s only the latest example of how the group has in recent years strayed from its original mission of defending speech, no matter how vile. Awash with money after former President Donald Trump was elected, the ACLU transformed into an organization that championed progressive causes, undermining the principled neutrality that helped make it a powerful advocate for the rights of clients ranging from Nazis to socialists.

It questioned the due process rights of college students accused of sexual assault and harassment under Title IX rules. It ran partisan ads against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh and for Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, a move that current Executive Director Anthony Romero told The New York Times was a mistake. The ACLU also called for the federal government to forgive $50,000 per borrower in student loans.

As the ACLU recedes from its mission, enter another free speech organization, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, or FIRE. Founded in 1999 to combat speech codes on college campuses, FIRE is expanding to go well beyond the university and changing its name to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. The group has raised $29 million toward a three-year “litigation, opinion research and public education campaign aimed at boosting and solidifying support for free-speech values.”

“I think there have been better moments for freedom of speech when it comes to the culture,” says FIRE’s president, Greg Lukianoff. “When it comes to the law, the law is about as good as it’s ever been. But when it comes to the culture, our argument is that it’s gotten a lot worse and that we don’t have to accept it.”

Lukianoff tells Reason that FIRE’s new initiatives have been in the works for years, but gained urgency during the COVID lockdowns. “Pretty much from day one, people have been asking us to take our advocacy off campus to an extent nationally,” he says. “But 2020 was such a scarily bad year for freedom of speech on campus and off, we decided to accelerate that process.” Despite 80 percent of campuses being closed and doing instruction remotely, Lukianoff says that FIRE received 50 percent more requests for help from college students and faculty. He also points to The New York Times‘ editorial page editor, James Bennet, getting squeezed out after running an article by Sen. Tom Cotton (R–Ark.) and high-profile journalists such as Bari Weiss, Andrew Sullivan, and Matt Yglesias “stepping away from [their publications], saying that the environment was too intolerant.”

FIRE is also expanding its efforts beyond legal advocacy and into promoting what Lukianoff calls “the culture of free speech.” As Politico reports, it will spend $10 million “in planned national cable and billboard advertising featuring activists on both ends of the political spectrum extolling the virtues of free speech.”

He says that people in their 40s and 50s grew up in a country where the culture of free speech was embedded in colloquial sayings and common attitudes. “Things like everyone’s entitled to their opinion, which is something you heard all the time when we were kids. It’s a free country, to each their own, statements of deep pluralism, like the idea that [you should] walk a mile in a man’s shoes,” he explains. “All of these things are great principles for taking advantage of pluralism, but they’ve largely sort of fallen out of usage due to a growing skepticism about freedom of speech, particularly on campus, that’s been about 40 years in the making.”

Lukianoff has nothing negative to say about the ACLU (in fact, he used to work there) and stresses that FIRE has worked with the organization since “day one” and continues to do so. But unlike the ACLU, FIRE isn’t at risk of turning into a progressive advocacy organization, partly because its staff is truly bipartisan.

That pluralistic pride extends to the groups funding FIRE, too. Lukianoff thinks that despite the rise of cancel culture, most Americans still understand the value of free speech, but they need to be encouraged to stand up for it. FIRE’s polling, he says, reveals that “it’s really a pretty small minority, particularly pronounced on Twitter, that is anti-free-speech philosophically and thinks that people should shut up and conform.”

For that reason, he’s upbeat that FIRE will succeed in helping to restore belief in the value and function of free speech.

Interview by Nick Gillespie. Edited by Regan Taylor.

June 23, 2022

QotD: Mis-preparing our kids for the future

I think that’s part of the issue, with our civilization at large. You see, the world is very complicated, and people are given the impression that it’s never been this complicated — which is a lie — and know for a fact that things are changing very fast. They no more find a path, than it dissolves and crumbles under them.

We’re preparing the new generation rottenly for this, too. Look, every generation is educated according to what their grandparents thought was desirable. Which is why I had the education that would have helped an upper class Portuguese Lady in the mid 19th century to make a good marriage and shine in society. For practical purposes, other than diplomacy […] the only use for my degree was academia by the time I took it. Though business desperately needed translators, we weren’t being taught office skills, or the terminology we needed to translate science or industrial stuff. (I learned those on my own, through running into them head first, as I learn practically anything.)

Kids now are being educated to the dreams of the early twentieth elites: for a communitarian world with a strong central government. They’re being told this is the future and what to expect, because when that idea made it into academia, and slowly worked itself through to curriculum and expectations, that was the future everyone EXPECTED. Even conservatives thought that the future would involve central planning. They just wanted to keep a little more individual freedom with it.

I remember blowing the world of Robert’s third grade teacher apart when we informed her that no, in the future there wouldn’t be a need for MORE group work, and that all creativity wouldn’t be communal (which frankly is funny. Creativity doesn’t work that way) but that it would be more individual, probably with people working on their piece of the project miles and miles away from the rest of the “team” and having to pull their weight alone. Dan and I explained why based on tech and trends, and all the poor woman kept saying is “that’s not what we were taught.”

Our kids were prepared not only for a world that doesn’t exist, but the world that idiot intellectuals (all intellectuals are idiots. They mostly don’t know a thing of the real world or real people) thought would come about, somehow, automagically. Think of Brave New World, but everyone is happy and doesn’t need the soma. (rolls eyes.)

And then we sneer at millenials for not finding their way, when people my age, who are self-directed and battlers, and have vocations, find ourselves caught in the grinding gears of change and get our goals and work broken over and over again, and yeah, also don’t find it easier to find our way.

Talk to the kids. Help them find something they’re “meant” to do (that’s not how it works, so make sure they know there isn’t only one goal and only one vocation, but there’s almost always something that their skills and ability are useful for RIGHT NOW. And the ability to learn more to change.) If needed, hook them on multiple streams of income. Help them see it’s possible. Dispel their illusions that life was ever easy.

Sure, in the past there were people who got “the one job” and stuck to it through thick and thin to the golden watch at the end. But I don’t think they were ever the majority. And by the time I came along, you couldn’t have any loyalty to your company, because it would have none to you.

Sarah Hoyt, “Finding Your Way”, According to Hoyt, 2019-02-18.