The Streetwise Professor explains what “stakeholder capitalism” is and why it needs to be staked through the heart to save western economies:

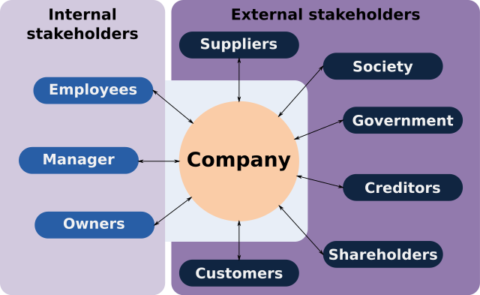

At its root, stakeholder capitalism represents a rejection – and usually an explicit one – of shareholder wealth maximization as the sole objective and duty of a corporation’s management. Instead, managers are empowered and encouraged to pursue a variety of agendas that do not promote and are usually inimical to maximizing value to shareholders. These agendas are usually broadly social in nature intended to benefit various non-shareholder groups, some of which may be very narrow (transsexuals) or others which may be all encompassing (all inhabitants of planet earth, human and non-human).

This system, such as it is, founders on two very fundamental problems: the Knowledge Problem and Agency problems.

The Knowledge Problem is that no single agent possesses the information required to achieve any goal – even if universally accepted. For example, even if reducing the risk of global temperature increases was broadly agreed upon as a goal, the information required to determine how to do so efficiently is vast as to be unknowable. What are the benefits of a reduction in global temperature by X degrees? The whole panic about global warming stems from its alleged impact on every aspect of life on earth – who can possibly understand anything so complex? And there are trade-offs: reducing temperature involves cost. The cost varies by the mix of measures adopted – the number of components of the mix is also vast, and evaluating costs is again beyond the capabilities of any human, no matter how smart, how informed, and how lavishly equipped with computational power. (Daron Acemoğlu, take heed).

[…]

Agency problems exist when due to information asymmetries or other considerations, agents may act in their own interests and to the detriment of the interests of their principals. In a simple example, the owner of a QuickieMart may not be able to monitor whether his late-shift employee is sufficiently diligent in preventing shoplifting, or exerts appropriate effort in cleaning the restrooms and so on. In the corporate world, the agency problem is one of incentives. The executives of a corporation with myriad shareholders may have considerable freedom to pursue their own interests using the shareholders’ money because any individual shareholder has little incentive to monitor and police the manager: other shareholders benefit from, and thus can free ride on, any individual’s efforts. So managers can, and often do, get away with extravagant waste of the resources owned by others placed in their control.

This agency problem is one of the costs of public corporations with diffuse ownership: this form of organization survives because the benefits of diversification (i.e., better allocation of risk) outweigh these costs. But agency costs exist, and increasing the scope of managerial discretion to, say, saving the world or achieving social justice inevitably increases these costs: with such increased scope, executives have more ways to waste shareholder wealth – and may even get rewarded for it through, say, glowing publicity and other non-pecuniary rewards (like ego gratification – “Look! I’m saving the world! Aren’t I wonderful?”)

H/T to Tim Worstall for the link.