The comments for that post were very active with suggestions for technological or strategic situations which would or would not make orbit-to-land operations (read: planetary invasions) unnecessary or obsolete, which were all quite interesting.

What I found most striking though was a relative confidence in how space battles would be waged in general, which I’ve seen both a little bit here in the comments and frequently more broadly in the hard-sci-fi community. The assumptions run very roughly that, without some form of magic-tech (like shields), space battles would be fought at extreme range, with devastating hyper-accurate weapons against which there could be no real defense, leading to relatively “thin-skinned” spacecraft. Evasion is typically dismissed as a possibility and with it smaller craft (like fighters) with potentially more favorable thrust-to-mass ratios. It’s actually handy for encapsulating this view of space combat that The Expanse essentially reproduces this model.

And, to be clear, I am not suggesting that this vision of future combat is wrong in any particular way. It may be right! But I find the relative confidence with which this model is often offered as more than a little bit misleading. The problem isn’t the model; it’s the false certainty with which it gets presented.

[…]

Coming back around to spaceships: if multiple national navies stocked with dozens of experts with decades of experience and training aren’t fully confident they know what a naval war in 2035 will look like, I find myself with sincere doubts that science fiction writers who are at best amateur engineers and military theorists have a good sense of what warfare in 2350 (much less the Grim Darkness of the Future Where There is Only War) will look like. This isn’t to trash on any given science fiction property mind you. At best, what someone right now can do is essentially game out, flow-chart style, probable fighting systems based on plausible technological systems, understanding that even small changes can radically change the picture. For just one example, consider the question “at what range can one space warship resolve an accurate target solution against another with the stealth systems and electronics warfare available?” Different answers to that question, predicated on different sensor, weapons and electronics warfare capabilities produce wildly different combat systems.

(As an aside: I am sure someone is already dashing down in the comments preparing to write “there is no stealth in space“. To a degree, that is true – the kind of Star Trek-esque cloaking device of complete invisibility is impossible in space, because a ship’s waste heat has to go somewhere and that is going to make the craft detectable. But detectable and detected are not the same: the sky is big, there are lots of sources of electromagnetic radiation in it. There are as yet undiscovered large asteroids in the solar-system; the idea of a ship designed to radiate waste heat away from enemies and pretend to be one more undocumented large rock (or escape notice entirely, since an enemy may not be able to track everything in the sky) long enough to escape detection or close to ideal range doesn’t seem outlandish to me. Likewise, once detected, the idea of a ship using something like chaff to introduce just enough noise into an opponent’s targeting system so that they can’t determine velocity and heading with enough precision to put a hit on target at 100,000 miles away doesn’t seem insane either. Or none of that might work, leading to extreme-range exchanges. Again, the question is all about the interaction of detection, targeting and counter-measure technology, which we can’t really predict at all.)

And that uncertainty attaches to almost every sort of technological interaction. Sensors and targeting against electronics warfare and stealth, but also missiles and projectiles against point-defense and CIWS, or any kind of weapon against armor (there is often an assumption, for instance, that armor is entirely useless against nuclear strikes, which is not the case) and on and on. Layered on top of that is what future technologies will even prove practical – if heat dissipation problems for lasers or capacitor limitations on railguns be solved problems, for instance. If we can’t quite be sure how known technologies will interact in an environment (our own planet’s seas) that we are intimately familiar with, we should be careful expressing confidence about how future technology will work in space. Consequently, while a science fiction setting can certainly generate a plausible model of future space combat, I think the certainty with which those models and their assumptions are sometimes presented is misplaced.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: August 14th, 2020”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-14.

January 15, 2023

QotD: The uncertain “certainties” of war in space

January 11, 2023

QotD: “Little” gods in the ancient world

When we teach ancient religion in school – be it high school or college – we are typically focused on the big gods: the sort of gods who show up in high literature, who create the world, guide heroes, mint kings. These are the sorts of gods – Jupiter, Apollo, Anu, Ishtar – that receive state cult, which is to say that there are rituals to these gods which are funded by the state, performed by magistrates or kings or high priests (or other Very Important People); the common folk are, at best, spectators to the rituals performed on their behalf by their social superiors.

That is not to say that these gods did not receive cult from the common folk. If you are a regular sailor on a merchant ship, some private devotion to Poseidon is in order; if you are a husband wishing for more children, some observance of Ishtar may help; if you are a farmer praying for rain, Jupiter may be your guy. But these are big gods, whose vast powers are unlimited in geographic scope and their right observance is, at least in part, a job for important people who act on behalf of the entire community. Such gods are necessarily somewhat distant and unapproachable; it may be difficult to get their attention for your particular issue.

Fortunately, the world is full up of smaller and more personal gods. The most pervasive of these are household gods – god associated with either the physical home, or the hearth (the fireplace), or the household/family as a social unit. The Romans had several of these, chiefly the Lares and Penates, two sets of gods who presided over the home. The Lares seem to have originally been hearth guardians associated with the family, while the Penates may have begun as the guardians of the house’s storeroom – an important place in an agricultural society! Such figures are common in other polytheisms too – the fantasy tropes of brownies, hobs, kobolds and the like began as similar household spirits, propitiated by the family for the services they provide.

(As an aside, the Lares and Penates provide an excellent example on how practice was valued more than belief or orthodoxy in ancient religion: when I say that they “seem” or “may have originally been”, that is because it was not entirely clear to the Romans, exactly what the distinction between the Lares and Penates were; ancient authors try to reconstruct exactly what the Penates are about from etymologies (e.g. Cic. De Natura Deorum 2.68) and don’t always agree! But of course, the exact origins of the Lares or the Penates didn’t matter so much as the power they held, how they ought to be appeased, and what they might do to you!)

Household gods also illuminate the distinctly communal nature of even smaller religious observances. The rituals in a Roman household for the Lares and Penates were carried out by the heads of the household (mostly the paterfamilias although the matron of the household had a significant role – at some point, we can talk about the hierarchy of Roman households, but now I just want to note that these two positions in the Roman family are not co-equal) on behalf of the entire family unit, which we should remember might well be multi-generational, including adult children with their own children – in just the same way that important magistrates (or in monarchies, the king or his delegates) might carry out rituals on behalf of the community as a whole.

There were other forms of little gods – gods of places, for instance. The distinction between a place and the god of that same place is often not strong – when Achilles enrages the god of the river Scamander (Iliad 20), the river itself rises up against him; both the river and the god share a name. The Romans cover many small gods under the idea of the genius (pronounced gen-e-us, with the “g” hard like the g in gadget); a genius might protect an individual or family […] or even a place (called a genius locus). Water spirits, governing bodies of water great and humble, are particularly common – the fifty Nereids of Greek practice, or the Germanic Nixe or Neck.

Other gods might not be particular to a place, but to a very specific activity, or even moment. Thus (these are all Roman examples) Arculus, the god of strongboxes, or Vagitanus who gives the newborn its first cry or Forculus, god of doors (distinct from Janus and Limentinus who oversaw thresholds and Cardea, who oversaw hinges). All of these are what I tend to call small gods: gods with small powers over small domains, because – just as there are hierarchies of humans, there are hierarchies of gods.

Fortunately for the practitioner, bargaining for the aid of these smaller gods was often quite a lot cheaper than the big ones. A Jupiter or Neptune might demand sacrifices in things like bulls or the dedication of grand temples – prohibitively expensive animals for any common Roman or Greek – but the Lares and Penates might be befriended with only a regular gift of grain or a libation of wine. A small treat, like a bowl of milk, is enough to propitiate a brownie. Many rituals to gods of small places amount to little more than acknowledging them and their authority, and paying the proper respect.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part IV: Little Gods and Big People”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-15.

January 7, 2023

QotD: The “camp followers” of a pre-modern army

It is worth keeping in mind that an army of 10,000 or 20,000 men was, by ancient or medieval standards, a mid-sized town or city moving across the landscape. Just as towns and cities created demand for goods that shaped life around them, so did armies (although they’d have to stay put to create new patterns of agriculture, though armies that did stay put did create new patterns of agriculture, e.g. the Roman limes). Thousands of soldiers demand all sorts of services and often have the money to pay for them and that’s in addition to what the army as an army needs. That in turn is going to mean that the army is followed by a host of non-combatants, be they attached to the soldiers, looking to turn a profit, or compelled to be there.

We can start with sutlers, merchants buying or selling from the soldiers themselves (the Romans called these fellows lixae, but also called other non-soldiers in the camp lixae as well, see Roth (2012), 93-4; they also call them mercatores or negotiatores, merchants). Sutlers could be dealing in a wide array of goods. Even for armies where ration distribution was regular (e.g. the Roman army), sutlers might offer for sale tastier and fancier rations: meat, better alcohol and so on. They might also sell clothing and other goods to soldiers, even military equipment: finding “custom” weapons and armor in the archaeology of military forts and camps is not uncommon. For less regularly rationed armies, sutlers might act as a supplement to irregular systems of food and pay, providing credit to soldiers who purchased rations to make up for logistics shortfalls, to collect when those soldiers were paid. By way of example, the regulations of the Army of Flanders issued in 1596 allowed for three sutlers per 200-man company of troops (Parker, op. cit.), but the actual number was often much higher and of course those sutlers might also have their own assistants, porters, wagons and so on which moved with the army’s camp. Women who performed this role in the modern period are often referred to by the French vivandière.

For some armies there would have been an additional class of sutlers: slave dealers. Enslaved captives were a major component of loot in ancient warfare and Mediterranean military operations into and through the Middle Ages. Armies would abduct locals caught in hostile lands they moved through or enemies captured in battles or sieges; naturally generals did not want to have to manage these poor folks in the long term and so it was convenient if slave-dealer “wholesalers” were present with the army to quickly buy the large numbers of enslaved persons the army might generate (and then handle their transport – which is to say traffic them – to market). In Roman armies this was a regularized process, overseen by the quaestor (an elected treasury official who handled the army’s finances) assigned to each army, who conducted regular auctions in the camp. That of course means that these slave dealers are not only following the army, but are doing so with the necessary apparatus to transport hundreds or even thousands of captives (guards, wagons, porters, etc.).

And then there is the general category of “camp follower”, which covers a wide range of individuals (mostly women) who might move with the camp. The same 1596 regulations that provided for just three sutlers per 200-man Spanish company also provided that there could be three femmes publiques (prostitutes), another “maximum” which must often have been exceeded. But prostitutes were not the only women who might be with an army as it moved; indeed the very same regulations specify that, for propriety’s sake, the femmes publiques would have to work under the “disguise of being washerwomen or something similar” which of course implies a population of actual washerwomen and such who also moved with the army. Depending on training and social norms, soldiers may or may not have been expected to mend their own clothes or cook their own food. Soldiers might also have wives or girlfriends with them (who might in turn have those soldier’s children with them); this was more common with professional long-service armies where the army was home, but must have happened with all armies to one degree or another. Roman soldiers in the imperial period were formally, legally forbidden from marrying, but the evidence for “soldier’s families” in the permanent forts and camps of the Roman Empire is overwhelming.

The tasks women attached to these armies have have performed varied by gender norms and the organization of the logistics system. Early modern gunpowder armies represent some of the broadest range of activities and some of the armies that most relied on women in the camp to do the essential work of maintaining the camp; John Lynn (op. cit., 118-163) refers to the soldiers and their women (a mix of wives, girlfriends and unattached women) collectively as “the campaign community” and it is an apt label when thinking about the army on the march. As Lynn documents, women in the camp washed and mended clothes, nursed the sick and cooked meals, all tasks that were considered at the time inappropriate for men. Those same women might also be engaged in small crafts or in small-scale trade (that is, they might also be sutlers). Finally, as Lynn notes, women who were managing food and clothing seem often to have become logistics managers for their soldiers, guarding moveable property during battles and participating in pillaging in order to scrounge enough food and loot for they and their men to survive. I want to stress that for armies that had large numbers of women in the camp, it was because they were essential to the continued function of the army.

And finally, you have the general category of “servants”. The range of individuals captured by this label is vast. Officers and high status figures often brought either their hired servants or enslaved workers with them. Captains in the aforementioned Army of Flanders seem generally to have had at least four or five servants (called mozos) with them, for instance; higher officers more. But it wasn’t just officers who did this. Indeed, the average company in the Army of Flanders, Parker notes, would have had 20-30 individual soldiers who also had mozos with them; one force of 5,300 Spanish veterans leaving Flanders brought 2,000 such mozos as they left (Parker, op. cit. 151).

Looking at the ancient world, many – possibly most – Greek hoplites in citizen armies seem to have very often brought enslaved servants with them to carry their arms and armor; such enslaved servants are a regular feature of their armies in the sources. The Romans called these enslaved servants in their armies calones; it was a common trope of good generalship to sharply restrict their number, often with limited success. At Arausio we are told there were half as many servants (calonum et lixarum) as soldiers (Liv. Per. 67, on this note Roth (2013), 105), though excessive numbers of calones et lixae was a standard marker of bad general and the Romans did lose badly at Arausio so we ought to take those figures with a grain of salt, as Livy (and his sources) may just be communicating that the generals there were bad. That said, the notion that a very badly led army might have as many non-combatants following it as soldiers is a common one in the ancient sources. And while Roman armies were considered notable in the ancient world for how few camp servants they relied on and thus how much labor and portage was instead done by the soldiers, getting Roman aristocrats to leave their vast enslaved household staff at home was notoriously difficult (e.g. Ps.Caes. BAfr. 54; Dio Cass. 50.11.6). Much like the early modern “campaign community”, our sources frequently treat these calones as part of the army they belonged to, even though they were not soldiers.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part I: The Problem”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-07-15.

January 3, 2023

QotD: Spartan dominance over the Peloponnese

Sparta initially seems to have attempted (Hdt. 1.66-8) to have extended its treatment of Messenia to other parts of the Peloponnese (namely Tegea) in the mid sixth-century – the failure of this policy led to a more measured effort to subjugate the Peloponnese more loosely into a Spartan-lead military league (the Peloponnesian League). This project was never fully completed: Argos – the next largest power in the Peloponnese proper, but a solidly second-tier power compared to Athens, Corinth, Sparta or Thebes – successfully resisted Spartan efforts to dominate it throughout the period. But on the whole, by the late 6th century, Sparta did exert a (perhaps somewhat loose – the trend in scholarship lately has been to stress the plastic and fairly loose organization of the Peloponnesian League) kind of dominance over the Peloponnese.

The core of this control lasted until 371, when Spartan defeat at the Battle of Leuktra shattered this control. Epaminondas, the Theban commander, used the opportunity to free the helots of Messenia and reform them into a polis to provide a local counter-weight to Sparta, while Arcadia and Elis split off from Sparta’s alliance to form their own defensive league against Sparta and, to top it off, a number of the perioikic communities – including the Spartans’ elite light infantry scouts, the Skiritae – along with various borderlands also formed the new polis of Megalopolis on the northern Spartan border – it promptly joined the Arcadian league (this polis would later give us the historian Polybius; his anti-Spartan stance comes out clearly in how he treats Cleomenes III). Sparta, surrounded now by hostile poleis who had once been allies, would spend the rest of Antiquity as a political non-entity, save for one brief effort to restore Spartan greatness in the 220s, crushed by the Macedonian Antigonids who were in no mood to entertain Spartan delusions of grandeur.

We might then say that Sparta is successful – though not entirely so (Argos!) – in establishing a hegemony over the Peloponnese, but only maintains it for c. 175 years. That’s not a bad run, but for the record of a larger state dominating its backyard, it is not tremendously impressive either.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

December 22, 2022

QotD: Sparta as the pre-eminent foe of tyranny

One of the ways that Sparta positioned itself was as the state which championed the freedom of the Greeks. Sparta had fought the Persian tyrant, had helped to oust tyrants in Athens and had later framed Athens itself as a “tyrant city”. Sparta itself had never had a tyrant (until Cleomenes III seized sole power in the 220s). On the flip side, Spartan hegemony was, apparently, little better than Athenian hegemony, given how Sparta’s own allies consistently reacted to it and Sparta would, in the end, do absolutely nothing to stop Philip II of Macedon from consolidating sole rule over Greece. When the call went out to once again resist a foreign invader in 338, Sparta was conspicuous in its absence.

It also matters exactly how tyranny is understood here. For the ancient Greeks, tyranny was a technical term, meaning a specific kind of one-man rule – a lot like how we use the word dictatorship to mean monarchies that are not kingdoms (though in Greece this word didn’t have quite so strong a negative connotation). Sparta was pretty reliable in opposing one-man rule, but that doesn’t mean it supported “free” governments. For instance, after the Peloponnesian War, Sparta foisted a brutal oligarchy – what the Athenians came to call “The Thirty Tyrants” – on Athens; their rule was so bad and harsh that it only lasted eight months (another feat of awful Spartan statecraft). Such a government was tyrannical, but not a tyranny in the technical sense.

But the Spartan reputation for fighting against tyrannies – both in the minds of the Greeks and in the popular consciousness – is predicted on fighting one very specific monarchy: the Achaemenids of Persia. […] This is the thing for which Sparta is given the most credit in popular culture, but Sparta’s record in this regard is awful. Sparta (along with Athens) leads the Greek coalition in the second Persian war and – as discussed – much of the Spartan reputation was built out of that. But Sparta had largely been a no-show during the first Persian war, and in the subsequent decades, Sparta’s commitment to opposing Persia was opportunistic at best.

During the late stages of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta essentially allied with Persia, taking funding and ships first from the Persian satrap Tissaphernes and later from Cyrus the Younger (a Persian prince and satrap). Sparta, after all, lacked the economic foundation to finance their own navy and the Spartans had – belatedly – realized that they needed a navy to defeat Athens. And of course the Persians – and any Spartan paying attention – knew that the Athenian navy was the one thing keeping Persia out of Greek affairs. So Sparta accepted Persian money to build up the fleets necessary to bring down the Athenian navy, with the consequence that the Ionian Greeks once again became subjects to the Persian Empire.

Subsequent Spartan diplomatic incompetence would lead to the Corinthian War (395-387), which turned into a nasty stalemate – due in part to the limitations of Spartan siege and naval capabilities. Unable to end the conflict on their own, the Spartans turned to Persia – again – to help them out, and the Persians brokered a pro-Spartan peace by threatening the Corinthians with Persian intervention in favor of Sparta. The subequent treaty – the “King’s Peace” (since it was imposed by the Persian Great King, Artaxerxes II) was highly favorable to Persia. All of Ionian, Cyprus, Aeolia and Carnia fell under Persian control and the treaty barred the Greeks from forming defensive leagues – meaning that it prevented the formation of any Greek coalition large enough to resist Persian influence. The treaty essentially made Sparta into Persia’s local enforcer in Greece, a role it would hold until its defeat in 371.

If Sparta held the objective of excluding Persian influence or tyranny from Greece, it failed completely and abjectly. Sparta opened not only the windows but also the doors to Persian influence in Greece – between 410 and 370, Sparta probably did more than any Greek state had ever or would ever do to push Greece into the Persian sphere of influence. Sparta would also refuse to participate in Alexander’s invasion of Persia – a point Alexander mocked them for by dedicating the spoils of his victories “from all of the Greeks, except the Spartans” (Arr. Anab. 1.16.7); for their part, the Spartans instead tried to use it as an opportunity to seize Crete and petitioned the Persians for aid in their war against Alexander, before being crushed by Alexander’s local commander, Antipater, in what Alexander termed “a clash of mice”.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

December 18, 2022

QotD: Citation systems and why they were developed

For this week’s musing I wanted to talk a bit about citation systems. In particular, you all have no doubt noticed that I generally cite modern works by the author’s name, their title and date of publication (e.g. G. Parker, The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road (1972)), but ancient works get these strange almost code-like citations (Xen. Lac. 5.3; Hdt. 7.234.2; Thuc. 5.68; etc.). And you may ask, “What gives? Why two systems?” So let’s talk about that.

The first thing that needs to be noted here is that systems of citation are for the most part a modern invention. Pre-modern authors will, of course, allude to or reference other works (although ancient Greek and Roman writers have a tendency to flex on the reader by omitting the name of the author, often just alluding to a quote of “the poet” where “the poet” is usually, but not always, Homer), but they did not generally have systems of citation as we do.

Instead most modern citation systems in use for modern books go back at most to the 1800s, though these are often standardizations of systems which might go back a bit further still. Still, the Chicago Manual of Style – the standard style guide and citation system for historians working in the United States – was first published only in 1906. Consequently its citation system is built for the facts of how modern publishing works. In particular, we publish books in codices (that is, books with pages) with numbered pages which are typically kept constant in multiple printings (including being kept constant between soft-cover and hardback versions). Consequently if you can give the book, the edition (where necessary), the publisher and a page number, any reader seeing your citation can notionally go get that edition of the book and open to the very page you were looking at and see exactly what you saw.

Of course this breaks down a little with mass-market fiction books that are often printed in multiple editions with inconsistent pagination (thus the endless frustration with trying to cite anything in A Song of Ice and Fire; the fan-made chapter-based citation system for a work without numbered or uniquely named chapters is, I must say, painfully inadequate.) but in a scholarly rather than wiki-context, one can just pick a specific edition, specify it with the facts of publication and use those page numbers.

However the systems for citing ancient works or medieval manuscripts are actually older than consistent page numbers, though they do not reach back into antiquity or even really much into the Middle Ages. As originally published, ancient works couldn’t have static page numbers – had they existed yet, which they didn’t – for a multitude of reasons: for one, being copied by hand, the pagination was likely to always be inconsistent. But for ancient works the broader problem was that while they were written in books (libri) they were not written in books (codices). The book as a physical object – pages, bound together at a spine – is more technically called a codex. After all, that’s not the only way to organize a book. Think of a modern ebook for instance: it is a book, but it isn’t a codex! Well, prior to codex becoming truly common in third and fourth centuries AD, books were typically written on scrolls (the literal meaning of libri, which later came to mean any sort of book), which notably lack pages – it is one continuous scroll of text.

Of course those scrolls do not survive. Rather, ancient works were copied onto codices during Late Antiquity or the Middle Ages and those survive. When we are lucky, several different “families” of manuscripts for a given work survive (this is useful because it means we can compare those manuscripts to detect transcription errors; alas in many cases we have only one manuscript or one clearly related family of manuscripts which all share the same errors, though such errors are generally rare and small).

With the emergence of the printing press, it became possible to print lots of copies of these works, but that combined with the manuscript tradition created its own problems: which manuscript should be the authoritative text and how ought it be divided? On the first point, the response was the slow and painstaking work of creating critical editions that incorporate the different manuscript traditions: a main text on the page meant to represent the scholar’s best guess at the correct original text with notes (called an apparatus criticus) marking where other manuscripts differ. On the second point it became necessary to impose some kind of organizing structure on these works.

The good news is that most longer classical works already had a system of larger divisions: books (libri). A long work would be too long for a single scroll and so would need to be broken into several; its quite clear from an early point that authors were aware of this and took advantage of that system of divisions to divide their works into “books” that had thematic or chronological significance. Where such a standard division didn’t exist, ancient libraries, particularly in Alexandria, had imposed them and the influence of those libraries as the standard sources for originals from which to make subsequent copies made those divisions “canon”. Because those book divisions were thus structurally important, they were preserved through the transition from scrolls to codices (as generally clearly marked chapter breaks), so that the various “books” served as “super-chapters”.

But sub-divisions were clearly necessary – a single librum is pretty long! The earliest system I am aware of for this was the addition of chapter divisions into the Vulgate – the Latin-language version of the Bible – in the 13th century. Versification – breaking the chapters down into verses – in the New Testament followed in the early 16th century (though it seems necessary to note that there were much older systems of text divisions for the Tanakh though these were not always standardized).

The same work of dividing up ancient texts began around the same time as versification for the Bible. One started by preserving the divisions already present – book divisions, but also for poetry line divisions (which could be detected metrically even if they were not actually written out in individual lines). For most poetic works, that was actually sufficient, though for collections of shorter poems it became necessary to put them in a standard order and then number them. For prose works, chapter and section divisions were imposed by modern editors. Because these divisions needed to be understandable to everyone, over time each work developed its standard set of divisions that everyone uses, codified by critical texts like the Oxford Classical Texts or the Bibliotheca Teubneriana (or “Teubners”).

Thus one cited these works not by the page numbers in modern editions, but rather by these early-modern systems of divisions. In particular a citation moves from the larger divisions to the smaller ones, separating each with a period. Thus Hdt. 7.234.2 is Herodotus, Book 7, chapter 234, section 2. In an odd quirk, it is worth noting classical citations are separated by periods, but Biblical citations are separated by colons. Thus John 3:16 but Liv. 3.16. I will note that for readers who cannot access these texts in the original language, these divisions can be a bit frustrating because they are often not reproduced in modern translations for the public (and sometimes don’t translate well, where they may split the meaning of a sentence), but I’d argue that this is just a reason for publishers to be sure to include the citation divisions in their translations.

That leaves the names of authors and their works. The classical corpus is a “closed” corpus – there is a limited number of works and new ones don’t enter very often (occasionally we find something on a papyrus or lost manuscript, but by “occasionally” I mean “about once in a lifetime”) so the full details of an author’s name are rarely necessary. I don’t need to say “Titus Livius of Patavium” because if I say Livy you know I mean Livy. And in citation as in all publishing, there is a desire for maximum brevity, so given a relatively small number of known authors it was perhaps inevitable that we’d end up abbreviating all of their names. Standard abbreviations are helpful here too, because the languages we use today grew up with these author’s names and so many of them have different forms in different languages. For instance, in English we call Titus Livius “Livy” but in French they say Tite-Live, Spanish says Tito Livio (as does Italian) and the Germans say Livius. These days the most common standard abbreviation set used in English are those settled on by the Oxford Classical Dictionary; I am dreadfully inconsistent on here but I try to stick to those. The OCD says “Livy”, by the by, but “Liv.” is also a very common short-form of his name you’ll see in citations, particularly because it abbreviates all of the linguistic variations on his name.

And then there is one final complication: titles. Ancient written works rarely include big obvious titles on the front of them and often were known by informal rather than formal titles. Consequently when standardized titles for these works formed (often being systematized during the printing-press era just like the section divisions) they tended to be in Latin, even when the works were in Greek. Thus most works have common abbreviations for titles too (again the OCD is the standard list) which typically abbreviate their Latin titles, even for works not originally in Latin.

And now you know! And you can use the link above to the OCD to decode classical citations you see.

One final note here: manuscripts. Manuscripts themselves are cited by an entirely different system because providence made every part of paleography to punish paleographers for their sins. A manuscript codex consists of folia – individual leaves of parchment (so two “pages” in modern numbering on either side of the same physical page) – which are numbered. Then each folium is divided into recto and verso – front and back. Thus a manuscript is going to be cited by its catalog entry wherever it is kept (each one will have its own system, they are not standardized) followed by the folium (‘f.’) and either recto (r) or verso (v). Typically the abbreviation “MS” leads the catalog entry to indicate a manuscript. Thus this picture of two men fighting is MS Thott.290.2º f.87r (it’s in Det Kongelige Bibliotek in Copenhagen):

MS Thott.290.2º f.87r which can also be found on the inexplicably well maintained Wiktenauer; seriously every type of history should have as dedicated an enthusiast community as arms and armor history.

And there you go.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 10, 2022”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-06-10.

December 14, 2022

QotD: The “tooth-to-tail ratio” in armies

The first issue is what in military parlance is called the “tooth to tail” ratio. This is the ratio of the number of actual combat troops (the “tooth”) to logistics and support personnel (the “tail”) in a fighting force. Note that these are individuals in the fighting force – the question of the supporting civilian economy is separate. The thing is, the tooth to tail ratio has tended to shift towards a longer tail over time, particular as warfare has become increasingly industrialized and technical.

The Roman legion, for instance, was essentially all tooth. While there was a designation for support troops, the immunes, so named because they were immune from having to do certain duties in camp, these fellows were still in the battle line when the legion fought. The immunes included engineers, catapult-operators, musicians, craftsmen, and other specialists. Of course legions were also followed around by civilian non-combatants – camp-followers, sutlers, etc. – but in the actual ranks, the “tail” was minimal.

You can see much the same in the organization of medieval “lances” – units formed around a single knight. The Burgundian “lance” of the late 1400s was composed of nine men, eight of which were combatants (the knight, a second horsemen, the coustillier, and then six support soldiers, three mounted and three on foot) and one, the page, was fully a non-combatant. A tooth-to-tail ratio of 8:1. That sort of “tooth-heavy” setup is common in pre-industrial armies.

The industrial revolution changes a lot, as warfare begins to revolve as much around mobilizing firepower, typically in the form of mass artillery firepower as in mobilizing men. We rarely in our fiction focus on artillery, but modern warfare – that is warfare since around 1900 – is dominated by artillery and other forms of [indirect] fires. Artillery, not tanks or machine guns, after all was the leading cause of combat death in both World Wars. Suddenly, instead of having each soldier carry perhaps 30-40kg of equipment and eat perhaps 1.5kg of food per day, the logistics concern is moving a 9-ton heavy field gun that might throw something like 14,000kg of shell per day during a barrage, for multiple days on end. Suddenly, you need a lot more personnel moving shells than you need firing artillery.

As armies motorized after WWI and especially after WWII, this got even worse, as a unit of motorized or mechanized infantry needed a small army of mechanics and logistics personnel handling spare parts in order to stay motorized. Consequently, tooth-to-tail ratios plummeted, inverted and then kept going. In the US Army in WWI, the ratio was 1:2.6 (note that we’ve flipped the pre-industrial ratio, that’s 2.6 non-combat troops for every front line combat solider), by WWII it was 1:4.3 and by 2005 it was 1:8.1. Now I should note there’s also a lot of variance here too, particularly during the Cold War, but the general trend has been for this figure to continue increasing as more complex, expensive and high-tech weaponry is added to warfare, because all of that new kit demands technicians and mechanics to maintain and supply it.

[NR: Early in WW2, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill frequently harassed his various North African generals for the disparity between the “ration strength” of their commands and the much-smaller number of combat troops deployed. If General Wavell had 250,000 drawing rations, Churchill (who last commanded troops in the field in mid-WW1) assumed that this meant close to 200,000 combat troops available to fight the Italians and (later) the Germans. This almost certainly contributed to the high wastage rate of British generals in the Western Desert.]

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, April 22, 2022”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-22.

December 10, 2022

QotD: The Western Roman Empire – “decline and fall” or “change and continuity”?

So who are our [academic] combatants? To understand this, we have to lay out a bit of the “history of the history” – what is called historiography in technical parlance. Here I am also going to note the rather artificial but importance field distinction here between ancient (Mediterranean) history and medieval European history. As we’ll see, viewing this as the end of the Roman period gives quite a different impression than viewing it as the beginning of a new European Middle Ages. The two fields “connect” in Late Antiquity (the term for this transitional period, broadly the 4th to 8th centuries), but most programs and publications are either ancient or medieval and where scholars hail from can lead to different (not bad, different) perspectives.

With that out of the way, the old view, that of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) and indeed largely the view of the sources themselves, was that the disintegration of the western half of the Roman polity was an unmitigated catastrophe, a view that held largely unchallenged into the last century; Gibbon’s great work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1789) gives this school its name, “decline and fall“. While I am going at points to gesture to Gibbon’s thinking, we’re not going to debate him; he is the “old man” of our title. Gibbon himself largely exists only in historiographical footnotes and intellectual histories; he is not at this point seriously defended nor seriously attacked but discussed as the venerable, but now out of date, origin point for all of this bickering.

The real break with that view came with the work of Peter Brown, initially in his The World of Late Antiquity (1971) and more or less canonically in The Rise of Western Christendom (1st ed. 1996; 2nd ed. 2003, 3rd ed. 2013). The normal way to refer to the Peter Brown school of thought is “change and continuity” (in contrast to the traditional “decline and fall”), though I rather like James O’Donnell’s description of it as the Reformation in late antique studies.

Among medievalists this reformed view, which focuses on continuity of culture and institutions from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages, remains essentially the orthodoxy, to the point that, for instance, the very recent (and quite excellent) The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (2021) can present this vision as an uncomplicated fact, describing the “so-called Fall of Rome” and noting that “there was never a moment in the next thousand years in which at least one European or Mediterranean ruler didn’t claim political legitimacy through a credible connection to the empire of the Romans” and that “the idea that Rome ‘fell’ on the other hand, relies upon a conception of homogeneity – of historical stasis … things changed. But things always change” (3-4, 12-3). As we’ll see, I don’t entirely disagree with those statements, but they are absolute to a degree that suggests there is no real challenge to the position. There have been a few cracks in this orthodoxy among medievalists, particularly the work of Robin Flemming (a revision, not a clear break, to be sure), to which we’ll return, but the cracks have been relatively few.

While some ancient historians also bought into this view, purchase there has always been uneven and seems, to me at least, now to be waning further. Instead, a process of what James O’Donnell describes as a “counter-reformation” (which he stoutly resists with his own The Ruin of the Roman Empire; O’Donnell is a declared reformer) is well underway, a response to the “change and continuity” narrative which seeks to update and defend the notion that there really was a fall of Rome and that it really was quite bad actually. This is not, I should note, an effort to revive Gibbon per se; it does not typically accept his understanding of the cause of this decline (and often characterizes exactly what is declining differently). Nevertheless, this position too is sometimes termed the “decline and fall” school. My own sense of the field is that while nearly all ancient historians will feel the need to concede at least some validity to the reformed “change and continuity” vision, that the counter-reformation school is the majority view among ancient historians at this point (in a way that is particularly evident in overview treatments like textbooks or the Cambridge Ancient History (second edition)). We’ll meet many of the core works of this revised “decline and fall” school as we go.

As O’Donnell noted in a 2005 review for the BMCR, the reformed school tends to be strongest in the study of the imperial east rather than the west (something that will make a lot of sense in a moment), and in religious and cultural history; the counter-reformation school is stronger in the west than the east and in military and political history, though as we’ll see, to that list must at this point now be added archaeology along with demographic and economic history, at which point the weight of fields tends to get more than a little lopsided.

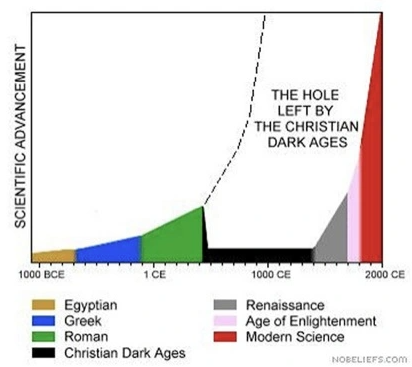

Those are our two knights – the “change and continuity” knight and the “decline and fall” knight (and our old man Gibbon, long out of his dueling days). To this we must add the nitwit: a popular vision, held by functionally no modern scholars, which represents the Middle Ages in their entirety as a retreat from a position of progress during the Roman period which was only regained during the “Renaissance” (generally represented as a distinct period from the Middle Ages) which then proceeded into the upward trajectory of the early modern period. Intellectually, this vision traces back to what Renaissance thinkers thought about themselves and their own disdain for “medieval” scholastic thinking (that is, to be clear, the thinking of their older teachers), a late Medieval version of “this ain’t your daddy’s rock and roll!”

But almost every intellectual movement represents itself as a radical break with the past (including, amusingly, many of the scholastics! Let me tell you about Peter Abelard sometime); as historians we do not generally accept such claims uncritically at face value. For a long time, well into the 19th century, the Renaissance’s cultural cachet in Europe (and the cachet of the classical period where it drew its inspiration) shielded that Renaissance claim from critique; that patina now having worn thin, most scholars now reject it, positioning the Renaissance as a continuation (with variations on the theme) of the Middle Ages, a smooth transition rather than a hard break. At the same time, knowledge of developments within the Middle Ages have made the image of one unbroken “Dark Age” untenable and made clear that the “upswing” of the early modern period was already well underway in the later Middle Ages and in turn had its roots stretching even deeper into the period. It is also worth noting here, that the term “Dark Age” has to do with the survival of evidence, not living conditions: the age was not dark because it was grim, it was dark because we cannot see it as clearly.

The popular version of this idea continues, however, to have a lot of sway in the popular conception of the Middle Ages, encouraged by popular culture that mistakes the excesses of the early modern period for “medieval” superstition and exaggerates the poverty of the medieval period (itself essentialized to its worst elements despite being approximately a millennia long), all summed up in this graph:

We are mostly going to just dunk relentlessly on this graph and yet we will not cover even half of the necessary dunking this graph demands. We may begin by noting that in its last century, the Roman Empire was Christian, a point apparently missed here.

While that sort of vision is not seriously debated by scholars, it needs to be addressed here too, in part because I suspect a lot of the energy behind the “change and continuity” position is in fact to counter some of the worst excesses of this thesis, which for simplicity, we’ll just refer to as “The Dung Ages” argument, but also because assessing how bad the fall of the Roman Empire in the West was demands that we consider how long-lasting any negative ramifications were.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Rome: Decline and Fall? Part I: Words”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-01-14.

December 6, 2022

QotD: Mao Zedong’s theory of “Protracted War”

The foundation for most modern thinking about this topic begins with Mao Zedong’s theorizing about what he called “protracted people’s war” in a work entitled – conveniently enough – On Protracted War (1938), though while the Chinese Communist Party would tend to subsequently represent the ideas there are a singular work of Mao’s genius, in practice he was hardly the sole thinker involved. The reason we start with Mao is that his subsequent success in China (though complicated by other factors) contributed to subsequent movements fighting “wars of national liberation” consciously modeled their efforts off of this theoretical foundation.

The situation for the Chinese Communists in 1938 was a difficult one. The Chinese Red Army has set up a base of power in the early 1930s in Jiangxi province in South-Eastern China, but in 1934 had been forced by Kuomintang Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek to retreat, eventually rebasing over 5,000 miles away (they’re not able to straight-line the march) in Shaanxi in China’s mountainous north in what became known as The Long March. Consequently, no one could be under any illusions of the relative power of the Chiang’s nationalist forces and the Chinese Red Army. And then, to make things worse, in 1937, Japan had invaded China (the Second Sino-Japanese War, which was a major part of WWII), beating back the Nationalist armies which had already shown themselves to be stronger than the Communists. So now Mao has to beat two armies, both of which have shown themselves to be much stronger than he is (though in the immediate term, Mao and Chiang formed a “United Front” against Japan, though tensions remained high and both sides expected to resume hostilities the moment the Japanese threat was gone). Moreover, Mao’s side lacks not only the tools of war, but the industrial capacity to build the tools of war – and the previous century of Chinese history had shown in stark terms how difficult a situation a non-industrial force faced in squaring off against industrial firepower.

That’s the context for the theory.

What Mao observed was that a “war of quick decision” would be one that the Red Army would simply lose. Because he was weaker, there was no way to win fast, so trying to fight a “fast” war would just mean losing. Consequently, a slow war – a protracted war – was necessary. But that imposes problems – in a “war of quick decision” the route to victory was fairly clear: destroy enemy armed forces and seize territory to deny them the resources to raise new forces. Classic Clausewitzian (drink!) stuff. But of course the Red Army couldn’t do that in 1938 (they’d just lose), so they needed to plan another potential route to victory to coordinate their actions. That is, they need a strategic framework – remember that strategy is the level of military analysis where we think about what our end goals should be and what methods we can employ to actually reach those goals (so that we are not just blindly lashing out but in fact making concrete progress towards a desired end-state).

Mao understands this route as consisting of three distinct phases, which he imagines will happen in order as a progression and also consisting of three types of warfare, all of which happen in different degrees and for different purposes in each phase. We can deal with the types of warfare first:

- Positional Warfare is traditional conventional warfare, attempting to take and hold territory. This is going to be done generally by the regular forces of the Red Army.

- Mobile Warfare consists of fast-moving attacks, “hit-and-run”, performed by the regular forces of the Red Army, typically on the flanks of advancing enemy forces.

- Guerrilla Warfare consists of operations of sabotage, assassination and raids on poorly defended targets, performed by irregular forces (that is, not the Red Army), organized in the area of enemy “control”.

The first phase of this strategy is the enemy strategic offensive (or the “strategic defensive” from the perspective of Mao). Because the enemy is stronger and pursuing a conventional victory through territorial control, they will attack, advancing through territory. In this first phase, trying to match the enemy in positional warfare is foolish – again, you just lose. Instead, the Red Army trades space for time, falling back to buy time for the enemy offensive to weaken rather than meeting it at its strongest, a concept you may recall from our discussions of defense in depth. The focus in this phase is on mobile warfare, striking at the enemy’s flanks but falling back before their main advances. Positional warfare is only used in defense of the mountain bases (where terrain is favorable) and only after the difficulties of long advances (and stretched logistics) have weakened the attacker. Mobile warfare is supplemented by guerrilla operations in rear areas in this phase, but falling back is also a key opportunity to leave behind organizers for guerrillas in the occupied zones that, in theory at least, support the retreating Red Army (we’ll come back to this).

Eventually, due to friction (drink!) any attack is going to run out of steam and bog down; the mobile warfare of the first phase is meant to accelerate this, of course. That creates a second phase, “strategic stalemate” where the enemy, having taken a lot of territory, is trying to secure their control of it and build new forces for new offensives, but is also stretched thin trying to hold and control all of that newly seized territory. Guerrilla attacks in this phase take much greater importance, preventing the enemy from securing their rear areas and gradually weakening them, while at the same time sustaining support by testifying to the continued existence of the Red Army. Crucially, even as the enemy gets weaker, one of the things Mao imagines for this phase is that guerrilla operations create opportunities to steal military materiel from the enemy so that the factories of the industrialized foe serve to supply the Red Army – safely secure in its mountain bases – so that it becomes stronger. At the same time (we’ll come back to this), in this phase capable recruits are also be filtered out of the occupied areas to join the Red Army, growing its strength.

Finally in the third stage, the counter-offensive, when the process of weakening the enemy through guerrilla attacks and strengthening the Red Army through stolen supplies, new recruits and international support (Mao imagines the last element to be crucial and in the event it very much was), the Red Army can shift to positional warfare again, pushing forward to recapture lost territory in conventional campaigns.

Through all of this, Mao stresses the importance of the political struggle as well. For the guerrillas to succeed, they must “live among the people as fish in the sea”. That is, the population – and in the China of this era that meant generally the rural population – becomes the covering terrain that allows the guerrillas to operate in enemy controlled areas. In order for that to work, popular support – or at least popular acquiescence (a village that doesn’t report you because it supports you works the same way as a village that doesn’t report you because it hates Chiang or a village that doesn’t report you because it knows that it will face violence reprisals if it does; the key is that you aren’t reported) – is required. As a result both retreating Red Army forces in Phase I need to prepare lost areas politically as they retreat and then once they are gone the guerrilla forces need to engage in political action. Because Mao is working with a technological base in which regular people have relatively little access to radio or television, a lot of the agitation here is imagined to be pretty face-to-face, or based on print technology (leaflets, etc), so the guerrillas need to be in the communities in order to do the political work.

Guerrilla actions in the second phase also serve a crucial political purpose: they testify to the continued existence and effectiveness of the Red Army. After all, it is very important, during the period when the main body of Communist forces are essentially avoiding direct contact with the enemy that they not give the impression that they are defeated or have given up in order to sustain will and give everyone the hope of eventual victory. Everyone there of course also includes the main body of the army holed up in its mountain bases – they too need to know that the cause is still active and that there is a route to eventual victory.

Fundamentally, the goal here is to make the war about mobilizing people rather than about mobilizing industry, thus transforming a war focused on firepower (which you lose) into a war about will – in the Clausewitzian (drink! – folks, I hope you all brought more than one drink for this …) sense – which can be won, albeit only slowly, as the slow trickle of casualties and defeats in Phase II steadily degrades enemy will, leading to their weakness and eventual collapse in Phase III.

I should note that Mao is very open that this protracted way of war would be likely to inflict a lot of damage on the country and a lot of suffering on the people. Casualties, especially among the guerrillas, are likely to be high and the guerrillas own activities would be likely to produce repressive policies from the occupiers (not that either Chiang’s Nationalists of the Imperial Japanese Army – or Mao’s Communists – needed much inducement to engage in brutal repression). Mao acknowledges those costs but is largely unconcerned by them, as indeed he would later as the ruler of a unified China be unconcerned about his man-made famine and repression killing millions. But it is important to note that this is a strategic framework which is forced to accept, by virtue of accepting a long war, that there will be a lot of collateral damage.

Now there is a historical irony here: in the event, Mao’s Red Army ended up not doing a whole lot of this. The great majority of the fighting against Japan in China was positional warfare by Chiang’s Nationalists; Mao’s Red Army achieved very little (except preparing the ground for their eventual resumption of war against Chiang) and in the event, Japan was defeated not in China but by the United States. Japanese forces in China, even at the end of the war, were still in a relatively strong position compared to Chinese forces (Nationalist or Communist) despite the substantial degradation of the Japanese war economy under the pressure of American bombing and submarine warfare. But the war with Japan left Chiang’s Nationalists fatally weakened and demoralized, so when Mao and Chiang resumed hostilities, the former with Soviet support, Mao was able to shift almost immediately to Phase III, skipping much of the theory and still win.

Nevertheless, Mao’s apparent tremendous success gave his theory of protracted war incredible cachet, leading it to be adapted with modifications (and variations in success) to all sorts of similar wars, particularly but not exclusively by communist-aligned groups.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

December 2, 2022

QotD: Rome’s legions settle down to permanent fortresses

The end of the reign of Augustus (in 14AD) is a convenient marker for a shift in Roman strategic aims away from expansion and towards a “frontier maintenance”. The usual term for both the Roman frontier and the system of fortifications and garrisons which defended it is the limes (pronounced “lim-ees”), although this wasn’t the only word the Romans applied to it. I want to leave aside for a moment the endless, complex conversation about the degree to which the Romans can actually be said to have strategic aims, though for what it is worth I am one of those who contends that they did. We’re mostly interested here in Roman behavior on the frontiers, rather than their intent anyway.

What absolutely does begin happening during the reign of Augustus and subsequently is that the Roman legions, which had spent the previous three centuries on the move outside of Italy, begin to settle down more permanently on Rome’s new frontiers, particularly along the Rhine/Danube frontier facing Central and Eastern Europe and the Syrian frontier facing the Parthian Empire. That in turn meant that Roman legions (and their supporting auxiliary cohorts) now settled into permanent forts.

The forts themselves, at least in the first two centuries, provide a fairly remarkably example of institutional inertia. While legionary forts of this early period typically replaced the earthwork-and-stakes wall (the agger and vallum) with stone walls and towers and the tents of the camp with permanent barracks, the basic form of the fort: its playing-card shape, encircling defensive ditches (now very often two or three ditches in sequence) remain. Of particular note, these early imperial legionary forts generally still feature towers which do not project outward from the wall, a stone version of the observation towers of the old Roman marching camp. Precisely because these fortifications are in stone they are often very archaeologically visible and so we have a fairly good sense of Roman forts in this period. In short then, put in permanent positions, Roman armies first constructed permanent versions of their temporary marching camps.

And that broadly seems to fit with how the Romans expected to fight their wars on these frontiers. The general superiority of Roman arms in pitched battle (the fancy term here is “escalation dominance” – that escalating to large scale warfare favored the heavier Roman armies) meant that the Romans typically planned to meet enemy armies in battle, not sit back to withstand sieges (this was less true on Rome’s eastern frontier since the Parthians were peer competitors who could rumble with the Romans on more-or-less even terms; it is striking that the major centers in the East like Jerusalem or Antioch did not get rid of their city walls, whereas by contrast the breakdown of Roman order in the third century AD and subsequently leads to a flurry of wall-building in the west where it is clear many cities had neglected their defensive walls for quite a long time). Consequently, the legionary forts are more bases than fortresses and so their fortifications are still designed to resist sudden raids, not large-scale sieges.

They were also now designed to support much larger fortification systems, which now gives us a chance to talk about a different kind of fortification network: border walls. The most famous of these Roman walls of course is Hadrian’s Wall, a mostly (but not entirely) stone wall which cuts across northern England, built starting in 122. Hadrian’s Wall is unusual in being substantially made out of stone, but it was of-a-piece with various Roman frontier fortification systems. Crucially, the purpose of this wall (and this is a trait it shares with China’s Great Wall) was never to actually prevent movement over the border or to block large-scale assaults. Taking Hadrian’s wall, it was generally manned by something around three legions (notionally; often at least one of the legions in Britain was deployed further south); even with auxiliary troops nowhere near enough to actually manage a thick defense along the entire wall. Instead, the wall’s purpose is slowing down hostile groups and channeling non-hostile groups (merchants, migrants, traders, travelers) towards controlled points of entry (valuable especially because import/export taxes were a key source of state revenue), while also allowing the soldiers on the wall good observation positions to see these moving groups. You can tell the defense here wasn’t prohibitive in part because the main legionary fortresses aren’t generally on the wall, but rather further south, often substantially further south, which makes a lot of sense if the plan is to have enemies slowed (but not stopped) by the wall, while news of their approach outraces them to those legionary forts so that the legions can form up and meet those incursions in an open battle after they have breached the wall itself. Remember: the Romans expect (and get) a very, very high success rate in open battles, so it makes sense to try to force that kind of confrontation.

This emphasis on controlling and channeling, rather than prohibiting, entry is even more visible in the Roman frontier defenses in North Africa and on the Rhine/Danube frontier. In North Africa, the frontier defense system was structured around watch-posts and the fossatum Africae, a network of ditches (fossa) separating the province of Africa (mostly modern day Tunisia) from non-Roman territory to its south. It isn’t a single ditch, but rather a system of at least four major segments (and possibly more), with watch-towers and smaller forts in a line-of-sight network (so they can communicate); the ditch itself varies in width and depth but typically not much more than 6m wide and 3m deep. Such an obstruction is obviously not an prohibitive defense but the difficulty of crossing is going to tend to channel travelers and raids to the intentional crossings or alternately slow them down as they have to navigate the trench (a real problem here where raiders are likely to be mounted and so need to get their horses and/or camels across).

On the Rhine and the Danube, the defense of the limes, the Roman frontier, included a border wall (earthwork and wood, rather than stone like Hadrian’s wall), similarly supported by legions stationed to the rear, with road networks positioned; once again, the focus is on observing threats, slowing them down and channeling them so that the legions can engage them in the field. This is a system based around observe-channel-respond, rather than an effort to block advances completely.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part II: Romans Playing Cards”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-11-12.

November 28, 2022

QotD: The Carolingian army

In essence, the Carolingian army was an odd sort of layer-cake, in part because it represented a transitional stage from the Germanic tribal levies of the earliest Middle Ages towards to emergence and dominance of the mounted aristocracy of the early part of the High Middle Ages (note: the Middle Ages is a long period, Europe is a big place, and it moves through a lot of military systems; to talk of a single “medieval European system” is almost always a dangerous over-generalization). The top of the layer-cake consisted of the mounted aristocrats, in basically the same organization as the lords of Rohan discussed above: the great magnates (including the king) maintained retinues of mounted warriors, while smaller (but still significant) landholders might fight as individual cavalrymen, being grouped into the retinues of the great magnates tactically, even if they weren’t subordinate to those magnates politically (although they were often both). These two groups – the mounted magnate with his retinue and the individual mounted warrior – would eventually become the nobility and the knightly class, but in the Carolingian period these social positions were not so clearly formed or rigid yet. We ought to understand that to speak of a Carolingian “knight” (translated for Latin miles, which ironically in classical Latin is more typically used of infantrymen) is not the same, in social consequence, as speaking of a 13th century knight (who might also be described as a miles in the Latin sources).

But below that in the Carolingian system, you have the select levy, relatively undistinguished (read: not noble, but often reasonably well-to-do) men recruited from the smaller farmers and townsfolk. This system itself seems to have derived from an earlier social understanding that all free men (or all free property owning men) held an obligation for military service; Halsall notes in the eighth century the term arimannus (Med. Lat.: army-man) or exercitalis (same meaning) as a term used to denote the class of free landowners on whom the obligation of military service fell in Lombard and later Frankish Northern Italy (the Roman Republic of some ten centuries prior had the same concept, the term for it was assidui). This was, on the continent at least, a part of the system that was in decline by the time of Charlemagne and especially after as the mounted retinues of the great magnates became progressively more important.

We get an interesting picture of this system in Charlemagne’s efforts in the first decades of the 800s to standardize it. Under Charlemagne’s system, productive land was assessed in units of value called mansi and (to simplify a complicated system) every four mansi ought to furnish one soldier for the army (the law makes provisions for holders of even half a mansus, to give a sense of how large a unit it was – evidently some families lived on fractions of a mansus). Families with smaller holdings than four mansi – which must have been most of them – were brigaded together to create a group large enough to be able to equip and furnish one man for the army. These fellows were expected to equip themselves quite well – shield, spear, sword, a helmet and some armor – but not to bring a horse. We should probably also imagine that villages and towns choosing who to send were likely to try to send young men in good shape for the purpose (or at least they were supposed to). Thus this was a draw-up of some fairly high quality infantry with good equipment. That gives it its modern-usage name, the select levy, because it was selected out of the larger free populace.

And I should note what makes these fellows different from the infantry who might often be found in the retinues of later medieval aristocrats is just that – these fellows don’t seem to have been in the retinues of the Carolingian aristocracy. Or at least, Charlemagne doesn’t seem to have imagined them as such. While he expected his local aristocrats to organize this process, he also sent out his royal officials, the missi to oversee the process. This worked poorly, as it turned out – the system never quite ran right (in part, it seems, because no one could decide who was in charge of it, the missi or the local aristocrats) and the decades that followed would see Carolingian and post-Carolingian rulers more and more dependent on their lords and their retinues, while putting fewer and fewer resources into any kind of levy. But Charlemagne’s last-gaps effort is interesting for our purpose because it illustrates how the system was supposed to run, and thus how it might have run (in a very general sense) in the more distant past. In particular, he seems to have imagined the select levy as a force belonging to the king, to be administered by royal officials (as the nation-in-arms infantry armies of the centuries before had been), rather than as an infantry force splintered into various retinues. In practice, the fragmentation of Charlemagne’s empire under his heirs was fatal for any hopes of a centralized army, infantry or otherwise, and probably hastened the demise of the system.

Beneath the select levy there was also the expectation that, should danger reach a given region, all free men would be called upon to defend the local redoubts and fortified settlements. This group is sometimes called the general levy. As you might imagine, the general levy would be of lower average quality and cohesion. It might include the very young and very old – folks who ought not to be picked out for the select levy for that reason – and have a much lower standard of equipment. After all, unlike select levymen, who were being equipped at the expense, potentially, of many households, general levymen were individual farmers, grabbing whatever they could. In practice, the general levy might be expected to defend walls and little else – it was not a field force, but an emergency local defense militia, which might either enhance the select levy (and the retinues of the magnates) or at least hold out until that field army could arrive.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Battle oF Helm’s Deep, Part IV: Men of Rohan”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-05-22.

November 24, 2022

QotD: Roman legionary fortified camps

The degree to which we should understand the Roman habit of constructing fortified marching camps every night as exceptional is actually itself an interesting question. Our sources disagree on the origins of the Roman fortified camp; Frontinus (Front. Strat 4.1.15) says that the Romans learned it from the Macedonians by way of Pyrrhus of Epirus but Plutarch (Plut. Pyrrhus 16.4) represents it the other way around; Livy, more reliable than either agrees with Frontinus that Pyrrhus is the origin point (Liv. 35.14.8) but also has Philip V, a capable Macedonian commander, stand in awe of Roman camps (Liv. 31.34.8). It’s clear there was something exceptional about the Roman camps because so many of our sources treat it as such (Liv. 31.34.8; Plb. 18.24; Josephus BJ 3.70-98). Certainly the Macedonians regularly fortified their camps (e.g. Plb. 18.24; Liv 32.5.11-13; Arr. Alex. 3.9.1, 4.29.1-3; Curtius 4.12.2-24, 5.5.1) though Carthaginian armies seem to have done this less often (e.g. Plb. 6.42.1-2 encamping on open ground is treated as a bold new strategy).

It is probably not the camps themselves, but their structure which was exceptional. Polybius claims Greeks “shirk the labor of entrenching” (Plb. 6.42.1-2) and notes that the stakes the Romans used to construct the wooden palisade wall of the camp are more densely placed and harder to remove (Plb. 18.18.5-18). The other clear difference Polybius notes is the order of Roman camps, that the Romans lay out their camp the same way wherever it is, whereas Greek and Macedonian practice was to conform the camp to the terrain (Plb. 6.42); the archaeology of Roman camps bears out the former whereas analysis of likely battlefield sites (like the Battle of the Aous) seem to bear out the latter.

In any case, the mostly standard layout of Roman marching camps (which in the event the Romans lay siege, become siege camps) enables us to talk about the Roman marching camp because as far as we can tell they were all quite similar (not merely because Polybius says this, but because the basic features of these camps really do seem to stay more or less constant.

The basic outline of the camp is a large rectangle with the corners rounded off, which has given the camps (and later forts derived from them) their nickname: “playing card” forts. The size and proportions of a fortified camp would depend on the number of legions, allies and auxiliaries present, from nearly square to having one side substantially longer than the other. This isn’t the place to get into the internal configuration of the camp, except to note that these camps seemed to have been standardized so that the layout was familiar to any soldier wherever they went, which must have aided in both building the camp (since issues of layout would become habit quickly) and packing it up again.

Now a fortified camp does not have the same defensive purpose as a walled city: the latter is intended to resist a siege, while a fortified camp is mostly intended to prevent an army from being surprised and to allow it the opportunity to either form for battle or safely refuse battle. That means the defenses are mostly about preventing stealthy approach, slowing down attackers and providing a modest advantage to defenders with a relative economy of cost and effort.

In the Roman case, for a completed defense, the outermost defense was the fossa or ditch; sources differ on the normal width and depth of the ditch (it must have differed based on local security conditions) but as a rule they were at least 3′ and 5′ wide and often significantly more than this (actual measured Roman defensive fossae are generally rather wider, typically with a 2:1 ratio of width to depth, as noted by Kate Gilliver. The earth excavated to make the fossa was then piled inside of it to make a raised earthwork rampart the Romans called the agger. Finally, on top of the agger, the Romans would place the valli (“stakes”) they carried to make the vallum. Vallum gives us our English word “wall” but more nearly means “palisade” or “rampart” (the Latin word for a stone wall is more often murus).

Polybius (18.18) notes that Greek camps often used stakes that hadn’t had the side branches removed and spaced them out a bit (perhaps a foot or so; too closely set for anyone to slip through); this sort of spaced out palisade is a common sort of anti-ambush defense and we know of similar village fortifications in pre- and early post-contact North America on the East coast, used to discourage raids. Obviously the downside is that when such stakes are spaced out, it only takes the removal of a few to generate a breach. The Roman vallum, by contrast, set the valli fixed close together with the branches interlaced and with the tips sharpened, making them difficult to climb or remove quickly.

The gateway obviously could not have the ditch cut across the entryway, so instead a second ditch, the titulum, was dug 60ft or so in front of the gate to prevent direct approach; the gate might also be reinforced with a secondary arc of earthworks, either internally or externally, called the clavicula; the goal of all of this extra protection was again not to prevent a determined attacker from reaching the gates, but rather to slow a surprise attack down to give the defender time to form up and respond.

And that’s what I want to highlight about the nature of the fortified Roman camp: this isn’t a defense meant to outlast a siege, but – as I hinted at last time – a defense meant to withstand a raid. At most a camp might need to withstand the enemy for a day or two, providing the army inside the opportunity to retreat during the night.