seangabb

Published Apr 7, 2024This sixth lecture in the course deals with the period of Greek history between the end of the Persian Wars and the assassination of Philip II of Macedon.

(more…)

April 12, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 6 – The Search for Stability

April 2, 2024

QotD: Supersizing the Polis, Roman-style

Discussing the Roman Republic after already looking at the normal structure of a polis offers an interesting vantage point. As we’ll see, the Roman Republic has a lot of the same features as a polis: a citizen body, magistrates, a citizen assembly, all structured around a distinct urban center and so on. On the other hand, as we’re going to see, the Romans have some different ideas about the res publica (that’s their phrase which gives us our word “republic”). They imagine the republic differently than a polis and that leads to some meaningful differences in its structure and nature, even though it seems to share a lot of “DNA” with a polis and in some sense could be described as an “overgrown” city-state.

Which leads into the other major difference: size. We’re going to be taking a snapshot of the Roman Republic, necessary because the republic changed over time. In particular what we’re going to look at here is really a snapshot of the republic as it functioned in the third and second centuries, what Roman historians call the “Middle Republic” (c. 287-91BC). Harriet Flower defines this period as part of “the republic of the nobiles” which as we’ll see is an apt title as well.

But even by the beginning of this period, the Roman Republic is enormous by the standards of a polis. While a polis like Athens or Sparta with total populations in the low hundreds of thousands was already very large by Greek standards, the Roman Republic was much bigger. We know that in Italy in 225 there was something on the order of three hundred thousand Roman citizens liable for conscription, which implies a total citizen population right around a million. And that massive polity in turn governed perhaps another two million other Italians who were Rome’s “socii” (“allies”), perhaps the social category at Rome closest to “resident foreigners” (metics) in Greek poleis. This is in Italy alone, not counting Rome’s “overseas” holdings (at that point, Sicily, Corsica and Sardinia). In short, the Roman Republic may in some ways be shaped like a polis, but it was a full order of magnitude larger than the largest poleis, even before it acquired provinces outside of Italy. As you may imagine, that has implications!

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part I: SPQR”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-07-21.

March 22, 2024

Rome conquered Greece … militarily, anyway

In The Critic, Gavin McCormick reviews Charles Freeman’s new book The Children of Athena: Greek writers and thinkers in the age of Rome, 150BC – 400AD:

“To a wise man,” said the first-century wonderworker Apollonius of Tyana, “everywhere is Greece.” That is to say, Greece is not a mere place, but a special state of mind. For Apollonius, on his extensive travels around the Greco-Roman world, the purported truth of this maxim is seldom open to doubt.

The author of Apollonius’s colourful biography, Philostratus, depicts his hero as not just a philosopher but also an impossibly accomplished champion of culture — a confounder of logic and expectations who could vanish in plain sight, now fascinating Roman emperors and foreign sages, now inspiring whole towns into acts of celebration and renewal. The guiding ideology that drove this hero is a heady mix of philosophy, religion, magic and political insouciance — or, to give it another name, Hellenism.

In the context of the third-century world, where Christianity was an increasingly noteworthy presence in the towns and cities of the Roman empire, pagans such as Philostratus were keen to highlight what their own tradition had to offer.

In fact, he seems almost to present his hero as a pagan rival to Jesus. And, in turn, Apollonius — in his successful renewal of the shrines and local cults of Hellas — seems to hint at what Philostratus would like to see happen in his own contemporary context.

Despite living under Rome, Apollonius (and Philostratus) wants to celebrate an emphatically Greek form of culture. The celebration of Greek culture in the Roman world was, of course, nothing new, and it was something the Romans themselves had long enjoyed.

Alongside their admiration for Greek literature, philosophy, art and architecture, there was the successful movement known as the “Second Sophistic” — whose parade of Greek-speaking intellectuals left a heavy imprint on the public life of the High Roman Empire.

But it is striking nonetheless that the virtues of Hellas — not Rome itself — were what many educated citizens of the empire turned to when they thought of cultural renewal. Indeed his was precisely the route taken later in the fourth century by the last pagan emperor of Rome, himself a champion of all things Greek, Julian the so-called Apostate.

Charles Freeman’s latest book, Children of Athena, is a highly readable tour through the lives and accomplishments of some of the great exponents of Greek culture under Rome. He introduces readers to a bracingly varied and energetic cast of characters — the geographers, doctors, polymaths, botanists, satirists, and orators are just part of the repertoire. In an early chapter, we meet the brilliant Greek historian Polybius, who wrote in the tradition of Herodotus and Thucydides, while training his sights on the rise of Rome in his own time.

March 20, 2024

QotD: Ancient Greek tyranny

The normal expectation for Greek tyranny is that the system works like the Empire from Star Wars: A New Hope, where the new tyrant abolishes the Senate, appoints his own cronies to formal positions as rulers and generally makes himself Very Obviously and Formally In Charge. But this isn’t how tyranny generally worked: the tyrant was Very Obviously but not formally in charge, because he ruled extra-constitutionally, rather than abolishing the constitution. This is what separates tyranny, a form of extra-constitutional one man rule, from monarchy, a form of traditional and thus constitutional one-man rule.

We see the first major wave of tyrannies emerging in Greek poleis in the sixth century, although this is also about the horizon where we can see political developments generally in the Greek world, still our sources seem to understand this development to have been somewhat novel at the time and it is certainly tempting to see the emergence of tyranny and democracy in this period both as responses to the same sorts of pressures and fragility found in traditional polis oligarchies, but again our evidence is thin. Tyrants tend to come from the elite, oligarchic class and often utilize anti-oligarchic movements (civil strife or stasis, στάσις) to come to power.

Because most poleis are small, the amount of force a tyrant needed to seize power was also often small. Polycrates supposedly seized power in Samos with just fifteen soldiers (Hdt. 3.120), though we may doubt the truth of the report and elsewhere Herodotus notes that he did so in conspiracy with his two brothers of whom he killed one and banished the other (Hdt. 3.39). I’ve discussed Peisistratos’ takeover(s) in Athens before but they were similarly small-ball affairs. In Corinth, Cypselus seized power by using his position as polemarch (war leader) to have the army (which, remember, is going to be a collection of the non-elite but still well-to-do citizenry, although this is early enough that if I call it a hoplite phalanx I’ll have an argument on my hands) expel the Bacchiadae, a closed single-clan oligarchy. A move by any member of the elite to put together their own bodyguard (even one just armed with clubs) was a fairly clear indicator of an attempt to form a tyranny and the continued maintenance of a bodyguard was a staple of how the Greeks understood a tyrant.

Having seized power, those tyrants do not seem to have abolished key civic institutions: they do not disband the ekklesia or the law courts. Instead, the tyrant controls these things by co-opting the remaining elite families, using violence and the threat of violence against those who would resist and installing cronies in positions of power. Tyrants also seem to have bought a degree of public acquiescence from the demos by generally targeting the oligoi, as with Cypselus and his son Periander killing and banishing the elite Bacchiadae from Corinth (Hdt. 5.92). But this is a system of government where in practice the laws appeared to still be in force and the major institutions appeared to still be functioning but that in practice the tyrant, with his co-opted elites, armed bodyguard and well-rewarded cadre of followers among the demos, monopolized power. And it isn’t hard to see how the fiction of a functioning polis government could be a useful tool for a tyrant to maintain power.

That extra-constitutional nature of tyranny, where the tyrant exists outside of the formal political system (even though he may hold a formal office of some sort) also seems to have contributed to tyranny’s fragility. Thales was supposedly asked what the strangest thing he had ever seen was and his answer was, “An aged tyrant” (Diog. Laert. 1.6.36) and indeed tyranny was fragile. Tyrants struggled to hold power and while most seem to have tried to pass that power to an heir, few succeed; no tyrant ever achieves the dream of establishing a stable, monarchical dynasty. Instead, tyrants tend to be overthrown, leading to a return to either democratic or oligarchic polis government, since the institutions of those forms of government remained.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Polis, 101, Part IIa: Politeia in the Polis”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-03-17.

March 19, 2024

Greek History and Civilization, Part 5 – The Greeks Fight Back

seangabb

Published Mar 17, 2024This fifth lecture in the course deals with the defeat of Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, ending with the creation of the Delian League and the varying fortunes of Xerxes and Themistocles.

(more…)

February 27, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 4 – The Ancient Greeks: The Great Invasion

seangabb

Published Feb 18, 2024This fourth lecture in the course deals with the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, ending with the glory of Thermopylae and the burning of Athens.

(more…)

February 21, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 3 – The Ancient Greeks: Rising Tensions with Persia

seangabb

Published Feb 18, 2024This third lecture in the course deals with the rise of the Persian Empire, and the growing tensions between the Persians and the Greeks, culminating in an account of the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC.

(more…)

“There’s a moral imperative to go dig out that villa … It could be the greatest archaeological treasure on earth”

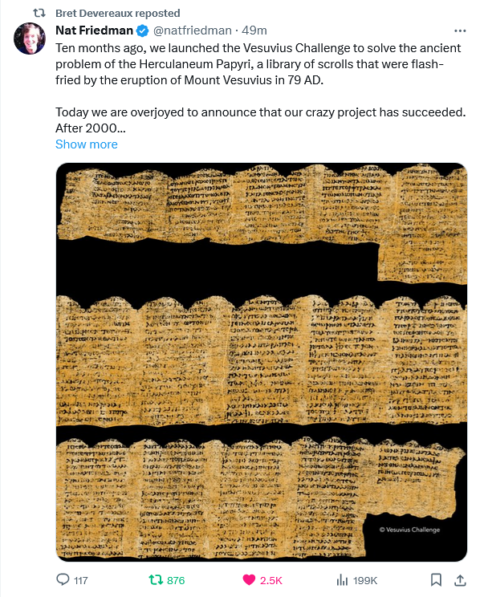

In City Journal, Nicholas Wade discusses the technical side of the ongoing attempts to read one of the Herculaneum scrolls:

A computer scientist has labored for 21 years to read carbonized ancient scrolls that are too brittle to open. His efforts stand at last on the brink of unlocking a vast new vista into the world of ancient Greece and Rome.

Brent Seales, of the University of Kentucky, has developed methods for scanning scrolls with computer tomography, unwrapping them virtually with computer software, and visualizing the ink with artificial intelligence. Building on his methods, contestants recently vied for a $700,000 prize to generate readable sections of a scroll from Herculaneum, the Roman town buried in hot volcanic mud from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

The last 15 columns — about 5 percent—of the unwrapped scroll can now be read and are being translated by a team of classical scholars. Their work is hard, as many words are missing and many letters are too faint to be read. “I have a translation but I’m not happy with it,” says a member of the team, Richard Janko of the University of Michigan. The scholars recently spent a session debating whether a letter in the ancient Greek manuscript was an omicron or a pi.

[…]

Seales has had to overcome daunting obstacles to reach this point, not all of them technical. The Italian authorities declined to make any of the scrolls available, especially to a lone computer scientist with no standing in the field. Seales realized that he had to build a coalition of papyrologists and conservationists to acquire the necessary standing to gain access to the scrolls. He was eventually able to x-ray a Herculaneum scroll in Paris, one of six that had been given to Napoleon. To find an x-ray source powerful enough to image the scroll without heating it, he had to buy time on the Diamond particle accelerator at Harwell, England.

In 2009, his x-rays showed for the first time the internal structure of a scroll, a daunting topography of a once-flat surface tugged and twisted in every direction. Then came the task of writing software that would trace the crumpled spiral of the scroll, follow its warped path around the central axis, assign each segment to its right position on the papyrus strip, and virtually flatten the entire surface. But this prodigious labor only brought to light a more formidable problem: no letters were visible on the x-rayed surface.

Seales and his colleagues achieved their first notable success in 2016, not with Napoleon’s Herculaneum scroll but with a small, charred fragment from a synagogue at the En-Gedi excavation site on the shore of the Dead Sea. Virtually unwrapped by the Seales software, the En-Gedi scroll turned out to contain the first two chapters of Leviticus. The text was identical to that of the Masoretic text, the authoritative version of the Hebrew Bible — and, at nearly 2,000 years old, its earliest instance.

The ink used by the Hebrew scribes was presumably laden with metal, and the letters stood out clearly against their parchment background. But the Herculaneum scroll was proving far harder to read. Its ink is carbon-based and almost impossible for x-rays to distinguish from the carbonized papyrus on which it is written. The Seales team developed machine-learning programs — a type of artificial intelligence — that scanned the unrolled surface looking for patterns that might relate to letters. It was here that Seales found use for the fragments from scrolls that earlier scholars had destroyed in trying to open them. The machine-learning programs were trained to compare a fragment holding written text with an x-ray scan of the same fragment, so that from the statistical properties of the papyrus fibers they could estimate the probability of the presence of ink.

February 20, 2024

Rome: Part 3 – The Expansion of Roman Power

seangabb

Published Feb 18, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 3: The Expansion of Roman Power

• The Conquest of Central Italy

• The Gallic Sack of 390 BC

• The Conquest of the Greek Cities

• Relations with Carthage

(more…)

February 13, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 2 – Sparta and Athens: Contrasting Societies

seangabb

Published Feb 11, 2024This second lecture in the course contrasts Athens and Sparta, the two leading societies in Greece — one a commercial society with high levels of personal freedom and citizen participation, the other a militarised oligarchy.

[NR: Some additional information to supplement Dr. Gabb’s lecture:

– “Citizenship” in the ancient and clasical world

– Sparta had Lycurgus, while Athens had Solon … who at least actually existed

– The Constitution of Athens

– The Constitution of the Spartans

– The Myth of Spartan Equality

– Relative wealth among the Spartiates

– Sparta’s military reputation as “the best warriors in all of Greece”

– Sparta – the North Korea of the Classical era

– Spartan glossary]

(more…)

February 11, 2024

QotD: Learning and re-learning the bloody art of war

The values composing civilization and the values required to protect it are normally at war. Civilization values sophistication, but in an armed force sophistication is a millstone.

The Athenian commanders before Salamis, it is reported, talked of art and of the Acropolis, in sight of the Persian fleet. Beside their own campfires, the Greek hoplites chewed garlic and joked about girls.

Without its tough spearmen, Hellenic culture would have had nothing to give the world. It would not have lasted long enough. When Greek culture became so sophisticated that its common men would no longer fight to the death, as at Thermopylae, but became devious and clever, a horde of Roman farm boys overran them.

The time came when the descendants of Macedonians who had slaughtered Asians till they could no longer lift their arms went pale and sick at the sight of the havoc wrought by the Roman gladius Hispanicus as it carved its way toward Hellas.

The Eighth Army, put to the fire and blooded, rose from its own ashes in a killing mood. They went north, and as they went they destroyed Chinese and what was left of the towns and cities of Korea. They did not grow sick at the sight of blood.

By 7 March they stood on the Han. They went through Seoul, and reduced it block by block. When they were finished, the massive railway station had no roof, and thousands of buildings were pocked by tank fire. Of Seoul’s original more than a million souls, less than two hundred thousand still lived in the ruins. In many of the lesser cities of Korea, built of wood and wattle, only the foundation, and the vault, of the old Japanese bank remained.

The people of Chosun, not Americans or Chinese, continued to lose the war.

At the end of March the Eighth Army was across the parallel.

General Ridgway wrote, “The American flag never flew over a prouder, tougher, more spirited and more competent fighting force than was Eighth Army as it drove north …”

Ridgway had no great interest in real estate. He did not strike for cities and towns, but to kill Chinese. The Eighth Army killed them, by the thousands, as its infantry drove them from the hills and as its air caught them fleeing in the valleys.

By April 1951, the Eighth Army had again proved Erwin Rommel’s assertion that American troops knew less but learned faster than any fighting men he had opposed. The Chinese seemed not to learn at all, as they repeated Chipyong-ni again and again.

Americans had learned, and learned well. The tragedy of American arms, however, is that having an imperfect sense of history Americans sometimes forget as quickly as they learn.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.

February 6, 2024

Greek History and Civilisation, Part 1 – What Makes the Greeks Special?

seangabb

Published Feb 1, 2024This first lecture in the course makes a case for the Greeks as the exceptional people of the Ancient World. They were not saints: they were at least as willing as anyone else to engage in aggressive wars, enslavement, and sometimes human sacrifice. At the same time, working without any strong outside inspiration, they provided at least the foundations for the science, mathematics, philosophy, art and secular literature of later peoples.

(more…)

QotD: Sparta’s actually mediocre military performance

Sparta was one of the largest Greek city-states in the classical period, yet it struggled to achieve meaningful political objectives; the result of Spartan arms abroad was mostly failure. Sparta was particularly poor at logistics; while Athens could maintain armies across the Eastern Mediterranean, Sparta repeatedly struggled to keep an army in the field even within Greece. Indeed, Sparta spent the entirety of the initial phase of the Peloponnesian War, the Archidamian War (431-421 B.C.), failing to solve the basic logistical problem of operating long term in Attica, less than 150 miles overland from Sparta and just a few days on foot from the nearest friendly major port and market, Corinth.

The Spartans were at best tactically and strategically uncreative. Tactically, Sparta employed the phalanx, a close-order shield and spear formation. But while elements of the hoplite phalanx are often presented in popular culture as uniquely Spartan, the formation and its equipment were common among the Greeks from at least the early fifth century, if not earlier. And beyond the phalanx, the Spartans were not innovators, slow to experiment with new tactics, combined arms, and naval operations. Instead, Spartan leaders consistently tried to solve their military problems with pitched hoplite battles. Spartan efforts to compel friendship by hoplite battle were particularly unsuccessful, as with the failed Spartan efforts to compel Corinth to rejoin the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League by force during the Corinthian War.

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

Bret Devereaux, “Spartans Were Losers”, Foreign Policy, 2023-07/22.

January 29, 2024

Ancient Roman Garum Revisited

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Nov 7, 2023

(more…)

January 26, 2024

QotD: How an oath worked in pre-modern cultures

You swear an oath because your own word isn’t good enough, either because no one trusts you, or because the matter is so serious that the extra assurance is required.

That assurance comes from the presumption that the oath will be enforced by the divine third party. The god is called – literally – to witness the oath and to lay down the appropriate curses if the oath is violated. Knowing that horrible divine punishment awaits forswearing, the oath-taker, it is assumed, is less likely to make the oath. Interestingly, in the literature of classical antiquity, it was also fairly common for the gods to prevent the swearing of false oaths – characters would find themselves incapable of pronouncing the words or swearing the oath properly.

And that brings us to a second, crucial point – these are legalistic proceedings, in the sense that getting the details right matters a great deal. The god is going to enforce the oath based on its exact wording (what you said, not what you meant to say!), so the exact wording must be correct. It was very, very common to add that oaths were sworn “without guile or deceit” or some such formulation, precisely to head off this potential trick (this is also, interestingly, true of ancient votives – a Roman or a Greek really could try to bargain with a god, “I’ll give X if you give Y, but only if I get by Z date, in ABC form.” – but that’s vows, and we’re talking oaths).

Thus for instance, runs an oath of homage from the Chronicle of the Death of Charles the Good from 1127:

“I promise on my faith that I will in future be faithful to count William, and will observe my homage to him completely against all persons in good faith and without deceit.”

Not all oaths are made in full, with the entire formal structure, of course. Short forms are made. In Greek, it was common to transform a statement into an oath by adding something like τὸν Δία (by Zeus!). Those sorts of phrases could serve to make a compact oath – e.g. μὰ τὸν Δία! (yes, [I swear] by Zeus!) as an answer to the question is essentially swearing to the answer – grammatically speaking, the verb of swearing is necessary, but left implied. We do the same thing, (“I’ll get up this hill, by God!”). And, I should note, exactly like in English, these forms became standard exclamations, as in Latin comedy, this is often hercule! (by Hercules!), edepol! (by Pollux!) or ecastor! (By Castor! – oddly only used by women). One wonders in these cases if Plautus chooses semi-divine heroes rather than full on gods to lessen the intensity of the exclamation (“shoot!” rather than “shit!” as it were). Aristophanes, writing in Greek, has no such compunction, and uses “by Zeus!” quite a bit, often quite frivolously.

Nevertheless, serious oaths are generally made in full, often in quite specific and formal language. Remember that an oath is essentially a contract, cosigned by a god – when you are dealing with that kind of power, you absolutely want to be sure you have dotted all of the “i”‘s and crossed all of the “t”‘s. Most pre-modern religions are very concerned with what we sometimes call “orthopraxy” (“right practice” – compare orthodoxy, “right doctrine”). Intent doesn’t matter nearly as much as getting the exact form or the ritual precisely correct (for comparison, ancient paganisms tend to care almost exclusively about orthopraxy, whereas medieval Christianity balances concern between orthodoxy and orthopraxy (but with orthodoxy being the more important)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.