I’ve never met Christopher Schwarz, but I’ve read a lot of his writing in books, magazine articles, and blog posts. He’s forgotten more about hand tool woodworking than I’ll ever know, and he’s amazingly generous in sharing his knowledge with others. He calls himself an anarchist, which often puzzles people who only know of anarchism from media-presented bomb-throwing nihilists and conspiratorial Russian stories. Here he explains what he means when he uses the term:

“Chris Schwarz and Meredith Schwarz” by jessamyn west is marked with CC0 1.0 .

I get asked a lot about what I mean by the word “anarchism”, and if I could please explain what I mean when I use that word.

My answer is always unsatisfying. Here’s why.

For the love of creamed corn, why would I publicly discuss ideas that are – for now – a crime in our country? Why would I say – for example – that I think that copyrights and patents on things that use public money are bullshit? That wars are founded on lies? And that the state – in general – seems to be a menace to peaceable living?

That would be stupid. Dumb nuts.

Also, I am a practitioner of anarchism, not a philosopher.

If you want to know more about American anarchism (and aesthetic anarchism, specifically), you need to ask a philosopher, not a front-of-house worker. Read Native American Anarchism (Hachette Books, 1983) by Eunice Minette Schuster for an easy on ramp. Or Josiah Warren’s Equitable Commerce (1852) for the full banana.

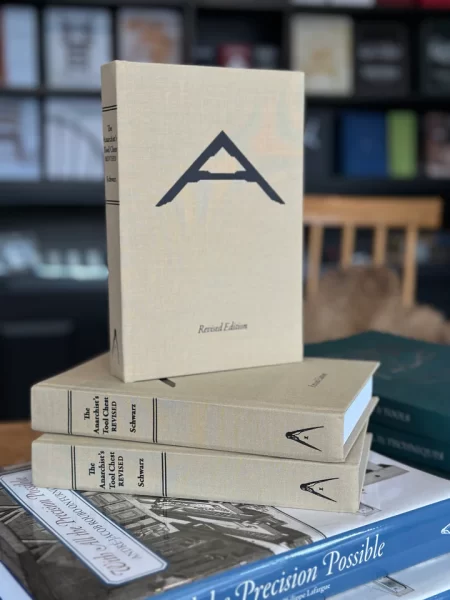

The Anarchist’s Tool Chest: Revised Edition by Christopher Schwarz – Link.

Or follow the trail of breadcrumbs left in The Anarchist’s Tool Chest to figure it out yourself. The book describes how to disrupt the furniture industry by building things that never need to be replaced. It’s also about how to jailbreak yourself from a tool industry that offers up aluminum jigs as a substitute for skill.

That book is not the only path. There are other ways to throw a bunch of ball bearings into the guts of the IKEA robots.

Buy antiques or used furniture. The other week I was in Savannah, Georgia, and visited one of my favorite antique stores. The price of handmade antiques has hit bottom. So-called “brown furniture” can be bought for less that the cost of the materials used to make it.

Even though I make furniture for a living, I sometimes save time and money by purchasing vintage industrial furniture for our warehouse, fulfillment center and workshop. Megan’s giant oak desk from the 1960s cost us zero dollars (we just had to move it from an insurance office). Our printer and scanning station? An old workbench from Pennsylvania. Our associate editors’ shared desk? A giant vintage drafting table from Sweden.

And if you think for a moment, there are other industries and organizations that can be farted upon by your actions. The clothing industry is even worse than the furniture industry when it comes to making flimsy crap and abusing workers.

Yes, you can buy ethically made jeans, shirts and socks. Yes, you will pay a premium for these items. And if you can afford that path, great. If you can’t, then buy secondhand clothing.

I’ve always wanted a pair of R.M. Williams boots but could never afford them on a writer’s salary. Last year I found a used pair for about $100 where the owner had ragged out the elastic part of the slip-on boots. It was a stupid easy fix. And now I have boots I shall wear at my funeral.

The other side of the equation is that I’m denying the new-boot-goofin’ industry my dollars. Forever. I don’t have to buy a pair of shoddily made boots that can’t be re-soled and will have to be replaced in a couple years. All my future “boot money” will go to our local cobbler so she can re-sole them every few years.