The late Lester Thurow was quite popular in the 1980s and 1990s for his incessant warnings that America was losing at the game of trade with other countries. Most ominous, Thurow (and others) warned, was our failure to compete effectively against the clever Japanese who, unlike us naive and complacent Americans, had the foresight to practice industrial policy, including the use of tariffs targeted skillfully and with precision. Trade, you see, said Thurow (and others) is indeed a contest in which the gains of the “winners” are the losses of the “losers”. Denials of this alleged reality come only from those who are bewitched by free-market ideology or blinded by economic orthodoxy.

And so – advised Thurow (and others) – we Americans really should step up our game by taking many production and consumption decisions out of the hands of short-sighted and selfish entrepreneurs, businesses, investors, and consumers and putting these decisions into the hands of the Potomac-residing wise and genius-filled faithful stewards of Americans’ interest.

Sound familiar? It should. While some of the details from decades ago of the news-making proponents of protectionism and industrial policy differ from the details harped on by today’s proponents of protectionism and industrial policy, the essence of the hostility to free trade and free markets of decades ago is, in most – maybe all – essential respects identical to the hostility that reigns today.

Markets in which prices, profits, and losses guide the decisions of producers and consumers were then – as they are today – asserted to be stupid, akin to a drunk donkey, while government officials (from the correct party, of course) alone have the knowledge, capacity, willpower, and power to allocate resources efficiently and in the national interest.

Nothing much changes but the names. Three or four decades ago protectionism and industrial policy in the name of the national interest was peddled by people with names such as Lester Thurow, Barry Bluestone, and Felix Rohatyn. Today protectionism and industrial policy in the name of the national interest is peddled by people with different names.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2020-03-12.

March 18, 2025

QotD: Lester Thurow and the other cheerleaders for “Industrial Policy” in the 1980s

March 5, 2025

Colt Boa: Rarest of the Snake Revolvers

Forgotten Weapons

Published 13 Nov 2024Of the seven revolvers Colt named after snakes, the rarest is the Colt Boa. Only a single production run of these were made totaling just 1,200 guns. They were made in 1985 as a custom order for the Lew Horton distribution company, which wanted something unique to offer its buyers. The Boa was an intermediary between the standard Colt MkV and the high-end Python. It was a 6-shot .357 Magnum with a full underlay and ventilated shroud. The only variation was in barrel length, as half were made with 4” barrels and half with 6” barrels. The serial numbers were “BOAxxxx”, with the 4” guns having odd numbers and the 6” ones getting even numbers. Five hundred of each were sold individually, but the first 100 of each length were packaged together into sequentially-numbered pairs in fancy cases.

The Boas all sold in 1985, and they are now the hardest to find for the Colt Snake collector. This particular pair is a gorgeous example of an original cased set, numbers 43 and 44.

(more…)

January 4, 2025

More on the “Boomers and Year Zero” thing

I sent the link I posted yesterday to Severian and asked for his reaction, saying that “Eric is three years older than me, so I’m on a cultural time-delay both for that and for not being American, but I still felt he was much more right than wrong here”. Sev’s thoughts as posted at FQ in the weekly mailbag post:

The upshot is that it isn’t the Boomers’ fault — they got tricked into it by Marxists, for whatever value of “it” is foremost in your mind, every time you’re tempted to say “OK, Boomer.”

I largely agree, with the caveat that “tricked” is a bit strong. There were conscious, indeed State-directed, attempts at outright cultural subversion — Raymond cites Yuri Bezmenov, and we’re all familiar with that. But there’s a limit to how much damage that kind of thing can do. What mostly happened, I think, circles back to that “excess calories” bit, above. That’s overly reductive — it’s a springboard for discussion, not a categorical statement — but the fact is, you need a certain baseline of physical security before Chesterton’s Fence becomes a thing. Or, as Confucius (or whoever) said, “The man with an empty belly has one problem, but the man with a full belly has a thousand”.

By 1960, at least in AINO, you had a critical mass of people who had never gone to bed hungry. Ever. And so it never crossed their minds that “going to bed hungry” is a thing people have to worry about. That had profound effects, that we’re still working through. It was never the case, ever, in the entire history of mankind, that the average person didn’t have to put some thought into where his next meal was coming from.

The entire human organism — physically, mentally, culturally — is oriented around the problem of caloric supply. Again, I acknowledge that’s overly reductive, but roll with me here: Our biochemistry has been profoundly fucked up by high fructose corn syrup, for the simple reason that a teaspoon of that shit has more, and more highly bioavailable, energy than an entire feast for our Paleolithic ancestors. At the risk of looking like a fool for using an engineering, especially an automotive, metaphor with this crowd, it’s like trying to run rocket fuel through a Model T.

You cannot blame the Boomers for fumbling a situation that has never before been seen, in the history of mankind.

And it’s even hard to blame them for not getting it, even now. One’s mental habits ossify, like one’s tastes, sometime in one’s twenties. It is very, very hard to break the conditioning of a lifetime, and it gets exponentially harder the older you get. I myself thought Ace of Normies was just crazy edgy — how can that maniac say these things?!? — when I first started reading him …

… back around 2004. That’s because I was in my 30s, which means my worldview was stuck a decade earlier. Even now, all my go-to cultural touchpoints are in the 1990s — Alanis, obviously, but pretty much all of them; the 21st century might as well not exist for me, culturally, if you go just by what I’ve written here. Which means that my own worldview tends to be kinda Boomerish, thanks to that weird telescoping effect TV had on the culture. The Boomers grew up watching TV, and then they made TV, such that you can ask anyone who was there — your typical college campus in 1994 was all but indistinguishable from a “liberal” campus in 1968 (your typical college campus in 1968 would’ve had sex-segregated dorms, a whole bunch of “married student housing”, and so on).

I got over it, obviously — and just as obviously tend to go a little overboard with my getting over it — but it takes tremendous effort. As I like to say, the Red Pill is really a suppository, usually administered by jackhammer. To expect a Donald Trump (born 1946), to say nothing of a million lesser lights, to fundamentally grok that it’s not 1968 anymore, is asking an awful lot. It is what it is.

November 16, 2024

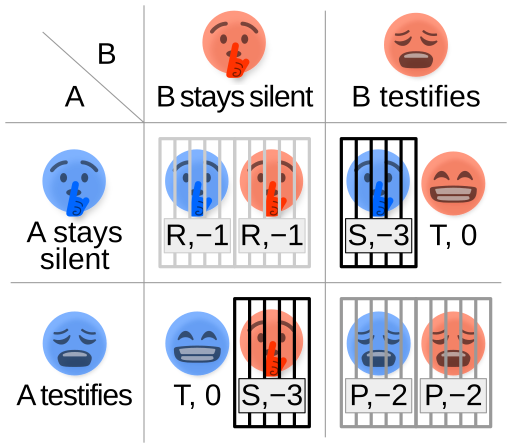

The 1980 Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Tournament

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander starts a post titled “The Early Christian Strategy” with some relevant back-story (fore-story?) involving game theory and the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma:

In 1980, game theorist Robert Axelrod ran a famous Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Tournament.

He asked other game theorists to send in their best strategies in the form of “bots”, short pieces of code that took an opponent’s actions as input and returned one of the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma outputs of COOPERATE or DEFECT. For example, you might have a bot that COOPERATES a random 80% of the time, but DEFECTS against another bot that plays DEFECT more than 20% of the time, except on the last round, where it always DEFECTS, or if its opponent plays DEFECT in response to COOPERATE.

In the “tournament”, each bot “encountered” other bots at random for a hundred rounds of Prisoners’ Dilemma; after all the bots had finished their matches, the strategy with the highest total utility won.

To everyone’s surprise, the winner was a super-simple strategy called TIT-FOR-TAT:

- Always COOPERATE on the first move.

- Then do whatever your opponent did last round.

This was so boring that Axelrod sponsored a second tournament specifically for strategies that could displace TIT-FOR-TAT. When the dust cleared, TIT-FOR-TAT still won — although some strategies could beat it in head-to-head matches, they did worst against each other, and when all the points were added up TIT-FOR-TAT remained on top.

In certain situations, this strategy is dominated by a slight variant, TIT-FOR-TAT-WITH-FORGIVENESS. That is, in situations where a bot can “make mistakes” (eg “my finger slipped”), two copies of TIT-FOR-TAT can get stuck in an eternal DEFECT-DEFECT equilibrium against each other; the forgiveness-enabled version will try cooperating again after a while to see if its opponent follows. Otherwise, it’s still state-of-the-art.

The tournament became famous because – well, you can see how you can sort of round it off to morality. In a wide world of people trying every sort of con, the winning strategy is to be nice to people who help you out and punish people who hurt you. But in some situations, it’s also worth forgiving someone who harmed you once to see if they’ve become a better person. I find the occasional claims to have successfully grounded morality in self-interest to be facile, but you can at least see where they’re coming from here. And pragmatically, this is good, common-sense advice.

For example, compare it to one of the losers in Axelrod’s tournament. COOPERATE-BOT always cooperates. A world full of COOPERATE-BOTS would be near-utopian. But add a single instance of its evil twin, DEFECT-BOT, and it folds immediately. A smart human player, too, will easily defeat COOPERATE-BOT: the human will start by testing its boundaries, find that it has none, and play DEFECT thereafter (whereas a human playing against TIT-FOR-TAT would soon learn not to mess with it). Again, all of this seems natural and common-sensical. Infinitely-trusting people, who will always be nice to everyone no matter what, are easily exploited by the first sociopath to come around. You don’t want to be a sociopath yourself, but prudence dictates being less-than-infinitely nice, and reserving your good nature for people who deserve it.

Reality is more complicated than a game theory tournament. In Iterated Prisoners’ Dilemma, everyone can either benefit you or harm you an equal amount. In the real world, we have edge cases like poor people, who haven’t done anything evil but may not be able to reciprocate your generosity. Does TIT-FOR-TAT help the poor? Stand up for the downtrodden? Care for the sick? Domain error; the question never comes up.

Still, even if you can’t solve every moral problem, it’s at least suggestive that, in those domains where the question comes up, you should be TIT-FOR-TAT and not COOPERATE-BOT.

This is why I’m so fascinated by the early Christians. They played the doomed COOPERATE-BOT strategy and took over the world.

May 20, 2024

The economic distortions of government subsidies

The Canadian federal and provincial governments are no strangers to the (political) attractions of picking winners and losers in the market by providing subsidies to some favoured companies at the expense not only of their competitors but almost always of the economy as a whole, because the subsidies almost never produce the kind of economic return promised. The current British government has also been seduced by the subsidies game, as Tim Congdon writes:

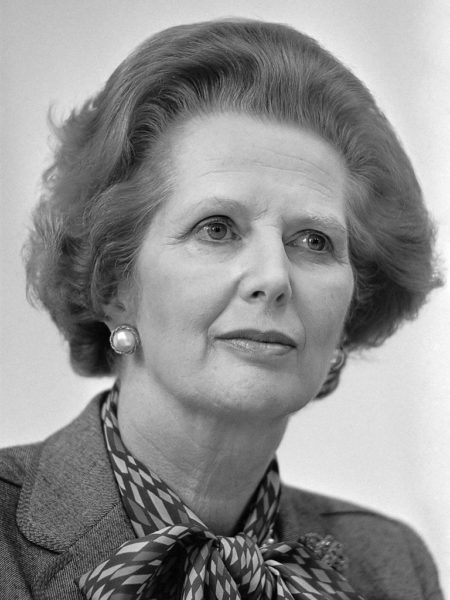

Former British Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1983. She was in office from May 1979 to November 1990.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Why do so many economists support a free market? By the phrase they mean a market, or even an economy dominated by such markets, where the government leaves companies and industries alone, and does not try to interfere by “picking winners” and subsidising them. Two of the economists’ arguments deserve to be highlighted.

The first is about the good use — the productivity — of resources. To earn a decent profit, most companies have to achieve a certain level of output to attract enough customers and to secure high enough revenue per worker.

If the government decides to give money to a favoured group of companies, these companies can survive even if they produce less, and obtain lower revenue per worker, than the others. The subsidisation of a favoured group of companies therefore lowers aggregate productivity relative to a free market situation.

In this column last month I compared the economically successful 1979–97 Conservative government with the economically unsuccessful 2010–2024 Conservative government, which is now coming to an end. In the context it is worth mentioning that Margaret Thatcher and her economic ministers had a strong aversion to government subsidies of any kind.

According to Professor Colin Wren of Newcastle University’s 1996 study, Industrial Subsidies: the UK Experience, subsidies were slashed from £5 billion (in 1980 prices) in 1979 to £0.3 billion in 1990. (In today’s prices that is from £23 billion to under £1.5 billion.)

Thatcher is controversial, and she always will be. All the same, the improvement in manufacturing productivity in the 1980s was faster than before in the post-war period and much higher than it has been since 2010. Further, one of Thatcher’s beliefs was that if the private sector refuses to pursue a supposed commercial opportunity, the public sector most certainly should not try to do so.

Such schemes as HS2 and the Hinkley Point nuclear boondoggle could not have happened in the 1980s or 1990s. They will result in pure social loss into the tens of billions of pounds and will undoubtedly reduce the UK’s productivity.

But there is a second, and also persuasive, general argument against subsidies and government intervention in industry. An attractive feature of a free market policy is its political neutrality. Because market forces are to determine commercial outcomes, businessmen are wasting their time if they lobby ministers and parliamentarians for financial aid.

Honest and straightforward tax-paying companies with British shareholders are rightly furious if they see the government channelling revenues towards other companies who have access to the right politicians and friendly civil servants. By definition, the damage to the UK’s interests is greatest if the recipients of government largesse are foreign.

May 12, 2024

The fascinating story of HMS Challenger (K07)

Sir Humphrey pens a long blog post about a late Cold War Royal Navy ship — officially just a “diving support vessel”, but apparently much more capable — most naval fans may never have heard about:

The story of HMS Challenger remains one of the most unusual of all post war Royal Navy vessels. Born in the late Cold War, she was in the eyes of the public a “white elephant” commissioned and never operationally used and sold after just a few years’ service at the end of the Cold War. She was to the few public that had heard of her, “the Warship that never was”. But revealing files in the National Archives tell a story of a ship that was designed to fill a range of highly secretive intelligence support functions and clandestine espionage activity that, had she been successful, would have made her perhaps one of the most vital intelligence collection assets in the UK. This article is about the untold story of HMS Challenger and why she deserves far more recognition than enjoyed to date.

The background of the Challenger story can be traced to the mid 1970s when the Royal Navy used the, by then positively venerable, warship HMS Reclaim to conduct diving support work. The Reclaim, commissioned in 1949 was the last warship in the RN to be designed and fitted with sails, that were occasionally used. Employed in diving support and salvage ops for 30 years, she was a vital asset for the recovery of crashed aircraft, support to diving and other assorted duties. But by 1975 she was also very old and out of date and requiring replacement (she paid off as the oldest operational vessel in the Royal Navy in 1979).

To replace her the Royal Navy developed Naval Staff Requirement 7003 and 7741, which were approved in 1976. These requirements set out the need for a replacement and the capabilities that were required. By this stage of the Cold War the world was a very different place both operationally and technologically from when HMS Reclaim entered service. There were significantly more undersea cables laid across the Atlantic, while the SOSUS network (a deep-water network of sonar systems intended to detect Russian submarines) had been delivered and expanded into UK waters in the early 1970s under project BACK SCRATCH. Additionally the Royal Navy had introduced a few years previously the Resolution class SSBN, which by 1976 had four submarines providing a Continuous At Sea Deterrent (CASD) with their Polaris missiles, as well as wider nuclear submarine operations. At the same time new technology was emerging including better diving capability, the rise of miniature submarines capable of both operating at immense depths and also the rise of rescue submarines for stranded nuclear submarines. Additionally technology had improved increasing the ability to recover items from the seabed.

When brought together this provided the RN with the opportunity to think afresh about how to replace Reclaim. The result was a set of requirements that were defined as follows:

The objective of NSR 7003 was to provide the Royal Navy with a Vessel and equipment capable of carrying out seabed operations. The requirement … is to find, inspect, work on and recover items on the seabed at all depths down to 300m with some capability to greater depths.

The specific missions for which the requirement was looking to cater for broke down into three main areas:

- Inspection, neutralisation or recovery of military equipment, including weapons;

- Operations in support of national offshore interests including research;

- Assistance with submarine escape and rescue and with underwater salvage

This represented a significant leap forward compared to Reclaim, which was limited to diving at up to 90m in very limited conditions, and would have provided the Royal Navy with an entirely new level of capabilities.

The decision was taken to proceed with the requirement and Challenger was ordered in 1979 and commissioned in 1983. What then follows is a sorry story of a ship being brought into service and having practically everything that could go wrong, going wrong. This article will not go into any depth on the story of what failed, as to do so would be a lengthy story. Suffice to say that a combination of faulty equipment, manufacturing challenges, fires and other damages and the reality that technical aspirations were not matched by practical delivery in reality meant that Challenger never really became operational.

Used for a series of trials until the late 1980s to prove her systems and see if they would work, she struggled to achieve what was expected of her. She had some success recovering toxic chemicals from the seabed from a sunken merchant ship in the 1980s and then conducting other demonstrations, such as deep diving and supporting submarine rescue trials. But she never lived up to the expectations placed on her, and at a time when the costs required to get her to the level of capability were far too high, and the defence budget was under pressure at a point when the Warsaw Pact threat was rapidly collapsing, the decision was taken to pay her off as a failed experiment even before the wider Options for Change plan was announced. This much is widely known to the public, but what is nowhere near as well known is the missions that Challenger was intended to carry out. Had she been successful, it would have made a very real difference to RN capabilities.

Why did the Royal Navy seem so determined to make a success of Challenger for so many years, to the extent of throwing ever more money at her, given these problems? In short because the missions she was designed to do made it worthwhile. Files in the archives clearly show that beyond the public line of “research” she was designed to carry out exceptionally sensitive missions. Although the original Naval Staff Requirement focused on three areas, by the time she entered service, this had expanded to at least 9 (possibly more). These were:

- Strategic Deterrent Force Security

- Seabed surveillance device support

- Nuclear weapon recovery

- Recovery of security and military sensitive material

- Crashed military aircraft recovery

- Submarine escape and rescue operations

- Salvage operations

- MOD research and data collection for other than intelligence agencies

- Miscellaneous operations in support of other government agencies

It can be seen that far from being just a diving support platform, Challenger was in fact an absolutely central part in providing assurance to the protection of CASD and ensuring the security of the nuclear deterrent and SOSUS. How would she have done this?

The files show that in the 1980s the UK had a different attitude to the US about protection of these routes due to geographic differences.

Javier Milei and the “Malvinas” question

Colby Cosh on how Argentine President Javier Milei handled British press inquiries about the Malvinas Falkland Islands like a boss:

I’ve been relishing a classic feast of British press overreaction to a BBC interview with the colourful libertarian president of Argentina, Javier Milei. The Beeb’s Ione Wells visited Milei at the Casa Rosada last week in Buenos Aires for a chat, and nothing like this could possibly happen without some talk about those damned islands — the Falklands or las Malvinas, depending on which country you believe to be their rightful sovereign.

Argentine leaders have to be careful how they talk about the Falklands (and about their uninhabited dependencies elsewhere in the South Atlantic). For decades regimes of left and right in Argentina have opportunistically kept the disputed islands at the forefront of the public imagination, fostering a spirit of delayed revenge. Sometimes this leads to daft verbal outbursts about “colonialism”, alongside game-playing with supplies and access to the islands. The constitution of Argentina contains language asserting “legitimate and imprescriptible sovereignty” over the rocks.

So anything a current Argentine leader says about the Falklands is bound to be scrutinized closely at home and in the United Kingdom. Milei is naturally impulsive, and has the particular problem that he is a political admirer of the late Margaret Thatcher. Wells tried to provoke him by bringing up the 1982 sinking of the General Belgrano and the consequent deaths of 323 Argentine sailors, which is still a slightly controversial episode of the Falklands War among the most self-hating shades of U.K. political opinion.

Milei, who had arranged a little display of Thatcher memorabilia in the room where the interview was held, sliced right through Wells’s Gordian knot. “Criticizing someone because of their nationality or race is very intellectually precarious,” he told Wells. “I have heard lots of speeches by Margaret Thatcher. She was brilliant. So what’s the problem?”

Even if you venerate Thatcher, who ordered the sinking of the Belgrano in very cold blood, you can perceive that this is a non sequitur. Milei is under no obligation to like a fellow neoliberal who was a military enemy of his own country. But one does remember that British statesmen have often been willing to express admiration for Napoleon I, Washington, Rommel and other killers of large numbers of British soldiers.

April 11, 2024

The CIA would “brief the press on matters of national importance … when ‘we, the CIA, wanted to circulate disinformation on a particular issue'”

Jon Miltimore outlines the fascinating revelations from 1983 about how the CIA directly manipulated American journalists to propagandize certain issues in the way the Agency desired:

One of Snepp’s many jobs at the Agency was to brief the press on matters of national importance. Or in Snepp’s words, when “we, the CIA, wanted to circulate disinformation on a particular issue”.

Snepp made this statement in a 1983 interview (see above) that I’d encourage readers to watch. In the video, the former CIA analyst discusses how the CIA manipulates journalists with lies and half-truths in pursuit of its own agendas.

For instance, if we wanted to get across to the American public that the North Vietnamese were building up there force structure in South Vietnam, I would go to a journalist and advise him that in the past 6 month X number of North Vietnamese forces had come down the Ho Chi Minh Trail system through southern Laos. There is no way a journalist can check that information, so either he goes with that information or he doesn’t. Usually the journalist goes with it, because it looks like some kind of exclusive.

What Snepp was describing was one of the most simple tactics the CIA has used for decades to control information. He said the success rate of planting these stories in the media was 70-80 percent.

“The correspondents we targeted were those who had terrific influence, the most respected journalists in Saigon,” Snepp said.

Snepp even offered the names of the journalists he successfully targeted: Bud Merrick of US News and World Report; Robert Chaplin of the New Yorker; Malcom Brown of the New York Times; and others.

Snepp worked his way into these journalists’ trust exactly as one would expect.

“I would be directed to cultivate them, to spend time with them at the Caravel Hotel or the Continental Hotel, to socialize with them, to slowly but surely gain their confidence,” Snepp said.

All of this sounds sleazy, but it gets worse.

April 3, 2024

Canada’s The Idler was intended for “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”

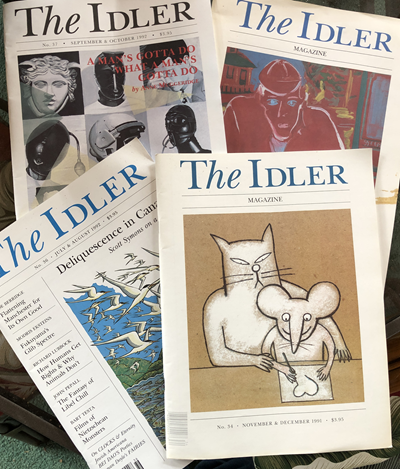

David Warren had already shuttered The Idler by the time I met him, but I was an avid reader of the magazine in the late 80s and early 90s. I doubt he remembers meeting me, as I was just one of a cluster of brand-new bloggers at the occasional “VRWC pub nights” in Toronto in the early aughts, but I always felt he was one of our elder statesmen in the Canadian blogosphere. He recalls his time as the prime mover behind The Idler at The Hub:

Some late Idler covers from 1991-92. I’ve got most of the magazine’s run … somewhere. These were the ones I could lay my hands on for a quick photo.

This attitude was clinched by our motto, “For those who read.” Note that it was not for those who can read, for we were in general opposition to literacy crusades, as, instinctively, to every other “good cause”. We once described the ideal Idler reader as “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”.

It was to be a magazine of elevated general interest, as opposed to the despicable tabloids. We — myself and the few co-conspirators — wished to address that tiny minority of Canadians with functioning minds. These co-conspirators included people like Eric McLuhan, Paul Wilson, George Jonas, Ian Hunter, Danielle Crittenden, and artists Paul Barker and Charles Jaffe. David Frum, Andrew Coyne, Douglas Cooper, Patricia Pearson, and Barbara Amiel also graced our pages.

I was the founder and would be the first editor. I felt I had the arrogance needed for the job.

I had spent much of my life outside the country and recently returned to it from Britain and the Far East. I had left Canada when I dropped out of high school because there seemed no chance that a person of untrammelled spirit could earn a living in Canadian publishing or journalism. Canada was, as Frum wrote in an early issue of The Idler, “a country where there is one side to every question”.

But there were several young people, and possibly many, with some literary talent, kicking around in the shadows, who lacked a literary outlet. These could perhaps be co-opted. (Dr. Johnson: “Much can be made of a Scotchman, if he be caught young.”)

The notion of publishing non-Canadians also occurred to me. The idea of not publishing the A.B.C. of official CanLit (it would be invidious to name them) further appealed.

We provided elegant 18th-century design, fine but not precious typography, tastefully dangerous uncaptioned drawings, shrewd editorial judgement, and crisp wit. I hoped this would win friends and influence people over the next century or so.

We would later be described as an “elegant, brilliant and often irritating thing, proudly pretentious and nostalgic, written by philosophers, curmudgeons, pedants, intellectual dandies. … There were articles on philosophical conundrums, on opera, on unjustifiably unknown Eastern European and Chinese poets.”

We struck the pose of 18th-century gentlemen and gentlewomen and used sentences that had subordinate clauses. We reviewed heavy books, devoted long articles to subjects such as birdwatching in Kenya or the anthropic cosmological principle, and we printed mottoes in Latin or German without translating them. This left our natural ideological adversaries scratching their heads.

March 4, 2024

“Whatever his flaws, Brian Mulroney was a serious person”

In the free-to-cheapskates teaser from this week’s dispatch from The Line, nice words are said in memory of the late Brian Mulroney, former Prime Minister of Canada:

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Mila Mulroney, Nancy Reagan, and President Ronald Reagan at the “Shamrock Summit”, 18 March, 1985.

Photo from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library via Wikimedia Commons.

Brian Mulroney died last week. He was 84.

The first thing you could be forgiven for taking away from the news coverage is how far we have fallen.

Brian Mulroney did big things. Negotiating Free Trade. Fighting Apartheid. Getting the Americans to crack down on acid rain. Comprehensive tax reform that saw the old Manufacturers’ Sales Tax (which taxed productivity) replaced with the GST. Sending Canadians to war in Desert Storm. Striking the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People which led to many of the legal advancements Indigenous communities were able to make through the 90s and into this century.

Even when he failed, as he did at Meech Lake, Brian Mulroney was trying to do something fundamentally transformative in Canadian politics.

And nobody who came after him had anywhere near that kind of guts. Not one of them.

There are things people will gripe about when it comes to Mulroney. Karlheinz Schreiber will be pretty close to the top of that list. Mulroney also tends to poll pretty poorly out west for any number of reasons ranging from a perceived over-emphasis on Quebec via Meech Lake and Charlottetown, to awarding the CF-18 maintenance contract to Montreal’s Canadair after (allegedly) promising it to Winnipeg-based Bristol Aerospace.

Mulroney was not beloved when he left office, to put it mildly. His party was basically annihilated in 1993, and the Canadian conservative movement shattered — it has still, in some ways, yet to fully recover. These are facts about which no one made more, or better, jokes than Mulroney himself. But that fall from esteem was almost never seen internationally. As he watched his contemporaries pre-decease him, Canadians got to see how respected the man was on the world stage. Mulroney was asked to eulogize American presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush as well as British prime minister Margaret Thatcher. In this, Mulroney embodied one of the greatest cultural cynicisms of this country: sometimes, the only way for us to claim a Canadian as one of our own is to first watch them make it abroad.

Mulroney’s great triumph is free trade. Yes, because it meant jobs for millions of Canadians. Yes, because it locked us into an economic pact with the world’s powerhouse economy. But also because, in doing it, he went head-on at one of this country’s great cliches: the idea that reflexive, Laurentian, anti-Americanism was somehow a basis for governing instead of just the hallmark of a deeply insecure cultural elite.

Nobody is picking those fights now. Nobody is taking on the big battles to remake the country. We have been treated to almost 30 years of some of the pettiest, small-ball sniping imaginable. Various wedge issues are dusted off by either side, and hurled like stale buns at their opponents. Culture wars are imported for the purposes of giving our political class something about which they can feign moral outrage. Our leaders are afraid of big things either because they’re hard, or because they are unlikely to pay off in a single four-year election cycle. Mulroney is, arguably, the last Canadian prime minister whose vision of what Canada is, or could be, was not limited by a four-year horizon.

We are a serious country that is not led by serious people. And that is brought into focus when you lose a serious person.

Whatever his flaws, Brian Mulroney was a serious person.

The Line‘s editors say that Mulroney wasn’t well liked on leaving office, but the utter obliteration of the Progressive Conservatives in the 1993 federal election can’t be completely blamed on him. His successor as PC leader, Kim Campbell, went out of her way to alienate western conservatives and libertarians during her brief time in office and during the election campaign that followed. She became Prime Minister with a surprising level of tentative support that she jettisoned in record time, taking her party from a majority in the House of Commons to two (2) seats — only one other Canadian PM has ever been defeated in their own riding (Arthur Meighen … but he had it happen twice, first in 1921 and again in 1926).

March 2, 2024

Brian Mulroney, RIP

In a guest post at Paul Wells’ Substack, Ian Brodie describes former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s role in ending the Cold War:

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Mila Mulroney, Nancy Reagan, and President Ronald Reagan at the “Shamrock Summit”, 18 March, 1985.

Photo from the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library via Wikimedia Commons.

Mulroney’s role has long been poo-poohed by intellectuals on the Canadian left. He was said to have an unhealthy obsession with pleasing the Americans. As a young boy, his fine voice won him an opportunity to entertain visiting American executives with a song. Amateur psychologists diagnosed a disturbing link between Mulroney’s having grown up in a company town, under the shadow of a US owned mill, and his reinvigoration of St. Laurent’s post-war grand strategy.

Mulroney never automatically fell in with US positions on the global issues of the day. His opposition to the apartheid regime in South Africa ran counter to the positions of both Reagan and Thatcher. But he drove the effort to link the American and Canadian economies through the free trade agreement. He backed our allies in the strategic competition with the Soviet bloc. And in helping to create the International Democratic Union, he helped put the west’s centre-right parties on the side of international political cooperation on the side of democracy, liberty, and the rule of law. The contrast with an earlier prime minister who could not bring himself to condemn the declaration of martial law in Poland a few years earlier was clear.

His personal relationships with a generation of American leaders gave substance to the transactional successes. As the Soviet Union came apart, he secured a spot for Canada as the first NATO country to recognize Ukraine’s independence and bolstered the independence movements of the Baltic republics. When Iraq tried to establish a precedent that, following the Cold War, large, powerful countries could invade their neighbours with impunity, Mulroney backed the US led coalition to liberate Kuwait with all the diplomatic and military power he had on hand.

And along the way, he so closely befriended both Reagan and the first Bush that he was given a privileged platform at two US state funerals, an honour never extended to a Canadian leader before and unlikely to be extended to one again soon.

Mulroney deserves to be remembered along with St. Laurent as Canada’s grand strategist of the 20th century. A trusted confidant of world leaders.

September 14, 2023

QotD: Going to “the mall”

“How was the mall?” Mom would ask when you got home.

“Eh, it was dead,” you might say.

“What did you do?”

“Nothing.”

Neither was true. Every trip to the mall had a routine. You’d swing by the sausage and cheese store for samples. You’d go to the record store to leaf through the sheaves of albums, nodding at the rock gods’ pictures on the wall, content in the cocoon of your generation’s culture. Head over to Chess King to see if there was something stylish you could wear on a date, if you ever had one; saunter casually into Spencer Gifts to look at the posters in the back, snicker at the naughty gifts, marvel at some electronic thing that cast colored patterns on the wall. Then you’d find a place, maybe by the fountain in the center, and watch the world go past in that agreeably tranquilized state of mall shopping.

Dead? Hardly. Okay, maybe it was the afternoon, low traffic. No movie you really wanted to see, the same stuff in the stores you saw last week. Of course you’d go back tomorrow, because that’s what you did with your friends. You went to the mall.

A dead mall is something else today: a vast dark cavern strewn with trash, stripped of its glitter, its escalators frozen, waiting for the claws to take it apart. The internet abounds with photos taken by surreptitious spelunkers, documenting the last days of once-prosperous malls. We look at these pictures with fascination and sadness. No one said they’d last forever. But there wasn’t any reason to think they wouldn’t. Hanging out as teens, we never thought we’d outlive the mall.

James Lileks, “The Allure of Ruins”, Discourse, 2023-06-12.

August 5, 2023

The rotten luck of the American Orient Express

Train of Thought

Published 5 May 2023In today’s video, we take a look at the American Orient Express, an attempt made by several businesses to replicate the charm and appeal of the real deal that just kept running into bad luck.

(more…)

August 1, 2023

Dire Straits – Tunnel Of Love (Rockpop In Concert, 19th Dec 1980)

Dire Straits

Published 28 Apr 2023Dire Straits performing ‘Tunnel Of Love’ at Rockpop in Concert on December 19th 1980.

Footage licensed from ZDF Enterprises. All rights reserved.

(more…)

July 9, 2023

Grain Elevator

NFB

Published 30 Sept 2015This documentary short is a visual portrait of “Prairie Sentinels”, the vertical grain elevators that once dotted the Canadian Prairies. Surveying an old diesel elevator’s day-to-day operations, this film is a simple, honest vignette on the distinctive wooden structures that would eventually become a symbol of the Prairie provinces.

(more…)