Secret Base

Published 8 Aug 2023This is the second episode of our seven-part docuseries, The History Of The Minnesota Vikings.

For the Vikings, the 1970s were so full of comedy, drama, and doomed snowmobiling expeditions that we had to split this decade into two episodes. And we STILL had to leave stuff out! What a team.

(more…)

August 21, 2023

What the parades are for | Dorktown

August 11, 2023

Toward a more perfect Homo Sovieticus

Ed West on the interplay between Soviet ideology and Soviet humour during the Cold War:

Krushchev, Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders review the Revolution parade in Red Square, 1962.

LIFE magazine photo by Stan Wayman.

Revolutions go through stages, becoming more violent and extreme, but also less anarchic and more authoritarian. Eventually the revolutionaries mellow, and grow dull. Once in power they become more conservative, almost by definition, and more wedded to a set of sacred beliefs, with the jails soon filling up with people daring to question them.

The Soviet system was based on the idea that humans could be perfected, and because of this they even rejected Mendelian genetics and promoted the scientific fraud Trofim Lysenko; he had hundreds of scientists sent to the Gulag for refusing to conform to scientific orthodoxy. Lysensko once wrote that: “In order to obtain a certain result, you must want to obtain precisely that result; if you want to obtain a certain result, you will obtain it … I need only such people as will obtain the results I need.”

Thanks in part to this scientific socialism, harvests repeatedly failed or disappointed, and in the 1950s they were still smaller than before the war, with livestock counts lower than in 1926.

“What will the harvest of 1964 be like?” the joke went: “Average – worse than 1963 but better than 1965”.

The Russians responded to their brutal and absurd system with a flourishing culture of humour, as Ben Lewis wrote in Hammer and Tickle, but after the death of Stalin the regime grew less oppressive. From 1961, the KGB were instructed not to arrest people for anti-communist activity but instead to have “conversations” with them, so their “wrong evaluations of Soviet society” could be corrected.

Instead, the communists encouraged “positive satire” – jokes that celebrated the Revolution, or that made fun of rustic stupidity. “An old peasant woman is visiting Moscow Zoo, when she sets eyes on a camel for the first time. ‘Oh my God,’ she says, ‘look what the Bolsheviks have done to that horse’.” The approved jokes blamed bad manufacturing on lazy workers, while the underground and popular ones blamed the economic system itself. This official satire was of course nothing of the sort, making fun of the old order and the foolish hicks who still didn’t embrace the Revolution and the future.

Communists likewise set up anti-western “satirical” magazines in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, where the same form of pseudo-satire could mock the once powerful and say nothing about those now in control.

Indeed in 1956, the East German Central Committee declared that the construction of socialism could “never be a subject for comedy or ridicule” but “the most urgent task of satire in our time is to give Capitalism a defeat without precedent”. That meant exposing “backward thinking … holding on to old ideologies”.

[…]

Leonid Brezhnev had a stroke in 1974 and another in 1976, becoming an empty shell and inspiring the gag: “The government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics has announced with great regret that, following a long illness and without regaining consciousness, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the President of the highest Soviet, Comrade Leonid Brezhnev, has resumed his government duties.”

Brezhnev was an absurd figure, presiding over a system few still believed in. His jacket was filled with medals – he had 260 awards by the time of his death – and when told that people were joking he was having chest expansion surgery to make room for all the medals he’d awarded himself, he apparently replied: “If they are telling jokes about me, it means they love me.”

July 28, 2023

QotD: “Stakeholder” Capitalism

Like many things faddish and ephemeral — disco, Pet Rocks, feathered hair, taking Michel Foucault seriously as an intellectual — the 1970s gave birth to the concept of stakeholder capitalism, one of the most unfortunate yet enduring of the bad ideas that polyester decade bequeathed us. At its essence, stakeholder capitalism is Marxian capitalism run through a lens of business ethics. It is the attempt to maintain authoritarian control over capitalism by displacing the Invisible Hand with a Velvet Glove, then using that glove, which hides an iron fist, to pound the world into adopting values that both assert and maintain its worldview. It is Theory applied to markets, marketing, wealth creation and management, and an overall globalized ethos of required and policed “virtue”, with the end goal being — as it always is under the discourses of Cultural Marxist thought — power: who has it, who controls it, and who uses it for their own ends most effectively and ruthlessly.

Of course, nobody participating in the push to replace shareholder capitalism with stakeholder capitalism would describe it this way. But then, euphemism and branding are each crucial tools in the Marxist’s verbal toolbox. So when you ask a stakeholder capitalist to describe stakeholder capitalism, what you ordinarily hear is that, as a business ethic, it combines the “sustainability” shareholder capitalism supposedly lacks with the “inclusivity” we’re not supposed to recognize is merely stultifying, policed conformity, the yield being a Woke capitalism that replaces production and consumption with “sharing and caring,” taking it out of the realm of the invisible and mechanical, as Adam Smith would have it, and placing it into the realm of values, where it can be used to shape the Greater Good the Marxist pretends he cares about. It’s fascism with a smiley face.

In the stakeholder capitalist system, investors aren’t — or at least, they shouldn’t be — solely interested in profits driven by production and consumption. And this is because to the stakeholder capitalist, itself a euphemism for collectivist corporatist, “it is well proven that our current form of Capitalism is inherently unsustainable because it requires endless growth on a planet with finite resources.”

Of course, none of this is “well proven” — the history of shareholder capitalism suggests the opposite, in fact, as innovation has led to the production of more and more out of less and less — but whether this is or isn’t the material case is incidental to those who are working on this inorganic worldwide paradigm shift commonly known as The Great Reset.

Because the move toward a “caring and sharing” worldwide economy, especially one that we’re told will be both sustainable and inclusive, requires those who care, those who share, and — most importantly, and at the very heart of the turn — those who get to determine what is cared about, who must do the sharing, and how most effectively to police the excesses that the ruling elite determine aren’t sustainable, while slowly dissolving the idea of the individual and his will to make way for an inclusive collective required to run the machinery of the self-installed Elect. It’s a global system of neo-Feudalism dressed in the finery of familiar values that have been deconstructed and re-signified, often without their consumers even aware that the values they reference — which were once commonly understood and largely shared by the civil society — are now their precise inverse: “tolerance”, thus, becomes the violent rejection of intolerance, as they define it; free speech is separated from “hate speech”, as they adjudicate it; individualism is but a controlling fiction maintained by the white male power structure that must be replaced by an ordered and value-determined collection of identity markers that construct you, while simultaneously acknowledging that there is no “you” beyond this assembly of discourses that assign your being its social situatedness, then places you within a collective of those with similar — though never identical — constructions. Once here, you are graded on the intersectional scale. Your relative worth and power come down to not to the content of your character, but rather to the collection and arrangement of your victimization tokens.

Jeff Goldstein, “Maybe I’ll be there to shake your hand, maybe I’ll be there to stakeholder capitalist the land”, protein wisdom reborn!, 2023-04-26.

July 9, 2023

Grain Elevator

NFB

Published 30 Sept 2015This documentary short is a visual portrait of “Prairie Sentinels”, the vertical grain elevators that once dotted the Canadian Prairies. Surveying an old diesel elevator’s day-to-day operations, this film is a simple, honest vignette on the distinctive wooden structures that would eventually become a symbol of the Prairie provinces.

(more…)

July 8, 2023

Canada’s Nuclear-Armed Cold War Interceptor: the story of the McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo

Polyus

Published 14 Aug 2020When Soviet or unidentified aircraft approached Canadian airspace in the 1960s and 70s, they were met by an iconic cold war interceptor. Armed with both conventional and nuclear weapons, they were a formidable foe in their day. It served to support NORAD and protect the Northern approaches into the North American heartland during the height of the Cold War. Although it was neither designed nor built in Canada, the reliable Voodoo remains a Canadian Cold War icon and was well loved by its ground crews and pilots.

0:00 Introduction

0:29 McDonnell F-101A development

1:06 F-101B Interceptor

3:11 Canada becomes involved with the Voodoo

4:15 The Nuclear question

5:08 Comparison with contemporaries

5:36 Operational History

8:04 Legacy and Retirement

8:48 Conclusion

(more…)

July 3, 2023

Nuclear power

One of the readers of Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten has contributed a review of Safe Enough? A History of Nuclear Power and Accident Risk, by Thomas Wellock. This is one of perhaps a dozen or so anonymous reviews that Scott publishes every year with the readers voting for the best review and the names of the contributors withheld until after the voting is finished:

Let me put Wellock and Rasmussen aside for a moment, and try out a metaphor. The process of Probabilistic Risk Assessment is akin to asking a retailer to answer the question “What would happen if we let a flaming cat loose into your furniture store?”

If the retailer took the notion seriously, she might systematically examine each piece of furniture and engineer placement to minimize possible damage. She might search everyone entering the building for cats, and train the staff in emergency cat herding protocols. Perhaps every once in a while she would hold a drill, where a non-flaming cat was covered with ink and let loose in the store, so the furniture store staff could see what path it took, and how many minutes were required to fish it out from under the beds.

“This seems silly — I mean, what are the odds that someone would ignite a cat?”, you ask. Well, here is the story of the Brown’s Ferry Nuclear Plant fire, in March 1975, which occurred slightly more than a year after the Rasmussen Report was released, as later conveyed by the anti-nuclear group Friends of the Earth.

Just below the plant’s control room, two electricians were trying to seal air leaks in the cable spreading room, where the electrical cables that control the two reactors are separated and routed through different tunnels to the reactor buildings. They were using strips of spongy foam rubber to seal the leaks. They were also using candles to determine whether or not the leaks had been successfully plugged — by observing how the flame was affected by escaping air.

The electrical engineer put the candle too close to the foam rubber, and it burst into flame.

The fire, of course, began to spread out of control. Among the problems encountered during the thirty minutes between ignition and plant shutdown:

- The engineers spent 15 minutes trying to put the fire out themselves, rather than sound the alarm per protocol;

- When the engineers decided to call in the alarm, no one could remember the correct telephone number;

- Electricians had covered the CO2 fire suppression triggers with metal plates, blocking access; and

- Despite the fact that “control board indicating lights were randomly glowing brightly, dimming, and going out; numerous alarms occurring; and smoke coming from beneath panel 9-3, which is the control panel for the emergency core cooling system (ECCS)”, operators tried the equivalent of unplugging the control panel and rebooting it to see if that fixed things. For ten minutes.

This was exactly the sort of Rube Goldberg cascade predicted by Rasmussen’s team. Applied to nuclear power plants, the mathematics of Probabilistic Risk Assessment ultimately showed that “nuclear events” were much more likely to occur than previously believed. But accidents also started small, and with proper planning there were ample opportunities to interrupt the cascade. The computer model of the MIT engineers seemed, in principle, to be an excellent fit to reality.

As a reminder, there are over 20,000 parts in a utility-scale plant. The path to nuclear safety was, to the early nuclear bureaucracy, quite simple: Analyze, inspect, and model the relationship of every single one of them.

June 28, 2023

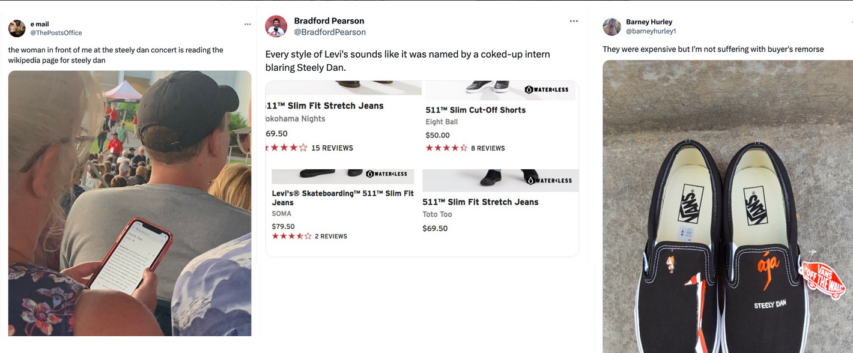

Ted Gioia’s confession – he’s a Dan stan

While I’ve never been much of a musicologist — and definitely not any kind of musician — I admit I had a very similar evolution of feeling toward the music of Steely Dan as Ted Gioia, who charts his progress from Never Dan to Dan stan:

I often make jokes about Steely Dan fans.

They’re bros and geeks and sad wannabes. But the painful truth is that I’m one of them now.

And if you don’t watch out, it could happen to you too.

At least I can laugh at myself. That’s good, because fans like me are the real target of the jokes.

And it’s true — we are a trifle obsessed.

If you’re a Dan stan, you see the band’s influence everywhere. Random patterns take on new Dan-esque shapes. For you it’s just rush hour traffic, but for us it’s a message from the cosmos.

But I wasn’t always like this. Once upon a time, I was a Steely Dan skeptic, a real Dan-o-phobe. I thought I was safe from their pernicious influence, but I was wrong.

This is my story.

June 25, 2023

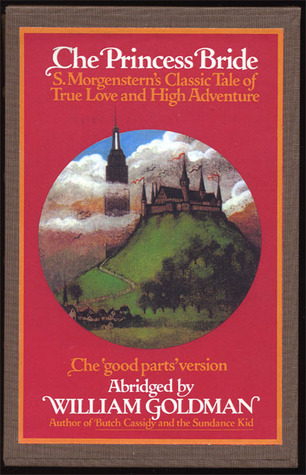

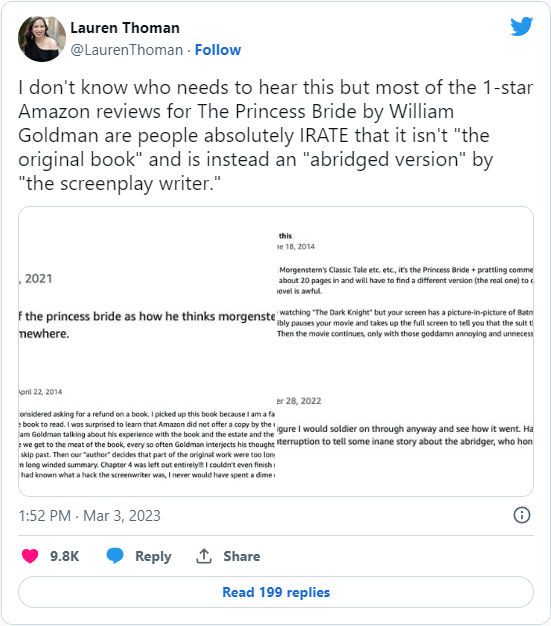

Fifty years after The Princess Bride was published

William Goldman’s novel The Princess Bride was not a blockbuster, nor did the movie adaptation get a huge box office when it released in 1987. Yet despite apparent early mediocrity, it became a cult classic. It’s now fifty years after the book came out, and Kevin Mims has a look back at both the novel and the movie:

Even by the eccentric standards of fantasy literature, William Goldman’s 1973 novel The Princess Bride is extremely odd. The book purports to be an abridged edition of a classic adventure story written by someone named Simon Morgenstern. In a bizarre introduction (more about which in a moment), Goldman claims merely to have acted as editor. Unlike Rob Reiner’s much-loved 1987 film adaptation, the book’s full title is The Princess Bride: S. Morgenstern’s Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure, The “Good Parts” Version. Yes, all that text actually appeared on the cover of the book’s first hardcover edition (all but the first three words have been scrubbed from the covers of most subsequent editions).

In the 1990s, I worked at a Tower Books store in Sacramento. Every few months, someone would come into the store and ask if we had an unabridged edition of S. Morgenstern’s The Princess Bride. The first time this happened, a younger colleague who had worked there longer than I had told my customer, “The Princess Bride was written by William Goldman. There is no S. Morgenstern. Goldman made him up.” The customer wasn’t convinced. “It’s metafiction,” my colleague explained. “A novel that comments on its own status as a text.” When the customer had left, my colleague told me that a lot of people still believe there is an original version of the novel available somewhere, written by Morgenstern. Having fallen in love with the story via the Hollywood film, they were now looking for the ur-text.

Although I was a big fan of William Goldman, I had never read The Princess Bride. My wife and I saw the film when it first appeared in American theaters, and we have rewatched it several times since on VHS and DVD. Only about 10 years ago did I actually get around to reading the novel. And when I did, I found myself sympathizing with all those people who still believe that, somewhere in the world, there exists an unedited edition.

In his introduction, Goldman tells us that S. Morgenstern was from the tiny European nation of Florin, located somewhere between Germany and Sweden, which is where the story’s action takes place. Such a place never existed, but it’s not surprising that many 21st-century American readers don’t know the names of every current and former European kingdom. European history is littered with microstates that rose briefly and then vanished without leaving much of a trace. Back in the 1990s, before Internet access became commonplace, confirming the existence of a small defunct European statelet would have involved a trip to the library.

But readers in the 1970s might have been more alive to Goldman’s ruse. Back then, metafiction was all the rage. John Barth became a literary superstar (among the academic set, anyway) with books like The Sot-Weed Factor (which, like The Princess Bride, is a fantastical comic adventure supposedly written by a fictional author) and Giles Goat-Boy (the text of which, Barth writes in the foreword, was said to have been written by a computer). In 1983, Goldman would publish a second novel behind the Morgenstern pseudonym, titled The Silent Gondoliers, but this time he removed all mention of himself, even from the copyright page.

Canada’s DeLorean – Bricklin SV-1

Ruairidh MacVeigh

Published 5 Sept 2020This week, it’s back to cars, and today we look at the history of a motoring scandal that took place 10 years before DeLorean and his DMC-12, but followed nearly the same notes; a rushed design, shady business practices, an inexperienced workforce in an impoverished part of the world, etc.

The Bricklin SV-1 may have looked good on paper, but in reality it was a severely flawed design that was ahead of its time in many aspects, but highly primitive in others.

(more…)

June 20, 2023

MAC Operational Briefcase (the H&K We Have at Home)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 3 Mar 2023Note: This video was proactively deleted to avoid a channel strike when YouTube went nuts over suppressors. I am reposting it today since they have rolled back those policy changes.

If a swanky outfit like H&K can make an “Operational Briefcase” with a submachine gun hidden inside it, then you can bet Military Armament Corporation is going to do the same! MAC made these briefcases for both the M10 and M11 submachine guns, and made a shortened suppressor for the M10 pattern guns to fit. They actually have a distinct advantage over the H&K type by fitting a gun with suppressor — but a distinct disadvantage in the exposed trigger bar on the bottom of the case, with no safety device of any kind.

Note: Possession of the briefcase with a semiauto MAC-type pistol that fits it is potentially seen as constructive possession of an AOW. A machine gun can be legally fitted in the case, but a semiauto pistol in it is considered a disguised weapon, and thus requires registration as an AOW.

(more…)

May 31, 2023

Alvin Toffler may have been utterly wrong in Future Shock, but I suspect his huge royalty cheques helped soften the pain

Ted Gioia on the huge bestseller by Alvin Toffler that got its predictions backwards:

Back in 1970, Alvin Toffler predicted the future. It was a disturbing forecast, and everybody paid attention.

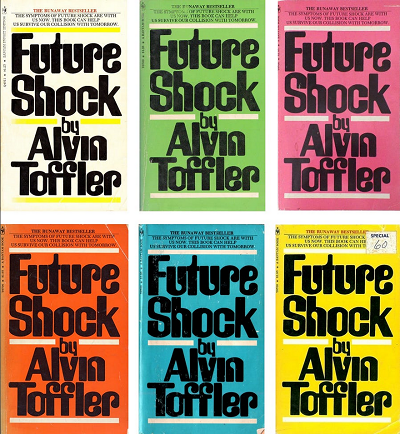

People saw his book Future Shock everywhere. I was just a freshman in high school, but even I bought a copy (the purple version). And clearly I wasn’t alone — Clark Drugstore in my hometown had them piled high in the front of the store.

The book sold at least six million copies and maybe a lot more (Toffler’s website claims 15 million). It was reviewed, translated, and discussed endlessly. Future Shock turned Toffler — previously a freelance writer with an English degree from NYU — into a tech guru applauded by a devoted global audience.

Toffler showed up on the couch next to Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. Other talk show hosts (Dick Cavett, Mike Douglas, etc.) invited him to their couches too. CBS featured Toffler alongside Arthur C. Clarke and Buckminster Fuller as trusted guides to the future. Playboy magazine gave him a thousand dollar award just for being so smart.

Toffler parlayed this pop culture stardom into a wide range of follow-up projects and businesses, from consulting to professorships. When he died in 2016, at age 87, obituaries praised Alvin Toffler as “the most influential futurist of the 20th century”.

But did he deserve this notoriety and praise?

Future Shock is a 500 page book, but the premise is simple: Things are changing too damn fast.

Toffler opens an early chapter by telling the story of Ricky Gallant, a youngster in Eastern Canada who died of old age at just eleven. He was only a kid, but already suffered from “senility, hardened arteries, baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin. In effect, Ricky was an old man when he died.”

Toffler didn’t actually say that this was going to happen to all of us. But I’m sure more than a few readers of Future Shock ran to the mirror, trying to assess the tech-driven damage in their own faces.

“The future invades our lives”, he claims on page one. Our bodies and minds can’t cope with this. Future shock is a “real sickness”, he insists. “It is the disease of change.”

As if to prove this, Toffler’s publisher released the paperback edition of Future Shock with six different covers — each one a different color. The concept was brilliant. Not only did Future Shock say that things were constantly changing, but every time you saw somebody reading it, the book itself had changed.

Of course, if you really believed Future Shock was a disease, why would you aggravate it with a stunt like this? But nobody asked questions like that. Maybe they were too busy looking in the mirror for “baldness, slack, and wrinkled skin”.

Toffler worried about all kinds of change, but technological change was the main focus of his musings. When the New York Times reviewed his book, it announced in the opening sentence that “Technology is both hero and villain of Future Shock“.

During his brief stint at Fortune magazine, Toffler often wrote about tech, and warned about “information overload”. The implication was that human beings are a kind of data storage medium — and they’re running out of disk space.

May 22, 2023

Dire Straits – “Sultans Of Swing” (Old Grey Whistle Test, 16th May 1978)

Dire Straits

Published 21 Oct 2022Dire Straits performing “Sultans Of Swing” in their first ever TV performance live on BBC’s The Old Grey Whistle Test in May, 1978. This performance took place three days before the UK release of their debut single of the same name.

(more…)

May 14, 2023

The life of the publishing world, fifty years ago

I point out things that prove that the past is a foreign country often enough that I have a blog tag for that purpose. When I first entered the work force, the conditions Ken Whyte describes for employees and managers at a publishing company weren’t all that uncommon (although they were already edging toward the endangered species list):

Fifty years ago, when Richard Charkin […] began his career in the book trade, telephones were wired to desktops and editors (male) wrote their letters and memos in longhand, turning them over to women in the typing pool who knocked them out on carbon paper because the publishing world was slow to photocopiers.

Employees smoked at their desks and drank at lunch. Men wore suits and ties and hats; women long skirts. Living wages were paid and even mid-level jobs came with a car. It was not uncommon for people to spend their whole careers at a single company.

Charkin started at Pergamon Press, an Oxford-based scientific publisher. It held an annual Miss Pergamon contest, essentially a beauty pageant for female employees. The winner received a titled sash, cloak, crown, and the opportunity to greet VIP visitors at company events. Pergamon was considered a progressive company for its time. Needless to say, this was before the dawn of the HR department. Also before marketing and IT departments, but publishers did have guilds, members of which met to discuss business at the pub.

In the mid-1970s, Charkin moved from Pergamon to Oxford University Press, which had traditions of its own. For instance, fortnightly editorial conferences were held at 11 a.m. on Tuesdays (but not in summer when everyone was off on extended vacations). Editors attended in robes and sat around an enormous table. In front of them were inkwells filled with fresh ink.

Charkin worked out of OUP’s Ely House offices in Mayfair. Tea ladies pushed trolleys down the corridors once in the morning and again in the afternoon, dispensing drinks and biscuits. There were three dining rooms on the premises: “one in the basement for all staff, which provided hearty and generously subsidized fare, while on the second floor there was an officers’ dining room, reserved for editors and middle managers, where meals were prepared by a fine chef and the drinks were free. At the very top of the building was the publisher’s dining room, which was exclusively for the use of the head of the London office … and his guests. The food here was sourced from Jackson’s of Piccadilly and the wine list was excellent, with the cellar being overseen by a senior manager at OUP whose job involved spending at least a month in France every year researching and ordering directly from vignerons.”

Class distinctions were rigid enough that two sets of bike racks were required, one for editors, the other for printers. There were a lot of printers: OUP still manufactured its own books and made its own paper, that very thin but indestructible variety once common in Bibles.

You’ll be shocked to learn that Oxford University Press, in operation since 1478, was in deep financial trouble by the 1980s.

In Toronto, this sort of thing was common in the bigger, long-established firms like banks, insurance companies, and even the major grocery chains (the Dominion head office facilities were reportedly top-notch in their day). I imagine it was even more the case in places like New York and Chicago.

May 13, 2023

Arnold Ridley – “Private Charles Godfrey” – a real story from Dad’s Army

The History Chap

Published 1 Feb 2023The story of Arnold Ridley — Private Charles Godfrey — Dad’s Army

After my last video all about Lance Corporal Jones in Dad’s Army I have been inundated by requests for the real story of another character from the classic comedy series: Private Godfrey.

Private Charles Godfrey, played by Arnold Ridley, is an ageing and slightly doddery member of the Walmington-on-Sea Home Guard platoon. His comrades are somewhat surprised and concerned when he announces that he was a conscientious objector during the First World War. However, thanks to his sister, the platoon learn his real (well, fictitious as it is a TV comedy show) story. Godfrey was indeed a conscientious objector but like many others he did volunteer to serve his country – just not to kill. Many men who felt likewise, joined the Army Medical Corps. Whilst not fighting they not only served their country and played a valuable role in the war effort but they also put themselves in harm’s way. Many of them became stretcher bearers, going out into no man’s land to fetch the wounded to safety. And many were decorated for their bravery.

William Coltman, became the most decorated NCO in the entire British army during the First World War … and he never fired a shot in anger!I will be telling the story of William Coltman VC in the near future.

Private Charles Godfrey was awarded the Military Medal for bravery during the battle of the Somme.

What makes Godfrey’s character all the more fascinating is that his actor, Arnold Ridley, was no conscientious objector but a volunteer in World War One. he was severly injured at the battle of the Somme in 1916 and discharged the following year.

Indeed, his injuries would influence how he played his character in Dad’s Army.

After the war, Ridley became a play writer. Arnold Ridley penned over 30 pays, the most famous of which was The Ghost Train written in 1923.

At the outbreak of the Second World War he once more volunteered to serve his country. Following the battle of Boulogne in 1940, he was evacuated to Britain, having been injured, once more, he was again given a medical discharge.

For the rest of the war he worked for ENSA – the forces entertainment organisation — and was a member of his local Home Guard. He continued his acting career through the 1940’s and 50’s before landing the role of Private Charles Godfrey in Dads Army in 1968. He was ever-present until the show ended in 1977. By then he was 81 years old.

Arnold Ridley died in 1984 and is buried in Bath Abbey.

(more…)

May 2, 2023

Dad’s Army: What Was The Military Career of Lance Corporal Jones?

The History Chap

Published 25 Jan 2023Lance Corporal Jack Jones is one of the most loved characters in the classic British comedy Dad’s Army. Constantly referring to his exploits in the Sudan, the North West Frontier (India) and the First World War.

So I thought I would make a short video exploring his long (& fictitious) military career.

The local butcher, Jack Jones, is a member of Walmington-on-Sea Home Guard during World War Two. This fictitious Home Guard unit are the stars of the classic BBC comedy: Dad’s Army.

What I found amazing is that the BBC created a back story for the character of Lance Corporal Jones. researching the medal ribbons that Jones wears on his Home Guard uniform I have put together a timeline of his military career in the 1st battalion, Warwickshire Regiment.

The story starts when young Jack Jones joins the Royal Warwickshire’s in 1884 as a drummer boy. He is to spend 31 years serving in the British army where he participates in the Gordon Relief Expedition, the re-conquest of Sudan under General Kitchener, the Boer War, the North West Frontier of India, and the First World War.