Skynea History

Published 22 Oct 2024For today’s video, we’ll be looking at the last of Canada’s aircraft carriers. Not typically a navy you associate with that kind of ship, but the Canadians actually operated three during the Cold War.

The third, HMCS Bonaventure, is an interesting one. A small ship, that operated aircraft at the very edge of her capability. And routinely baffled American pilots in the process.

Yet, she was also a ship that came to an end before her time. Decommissioned and scrapped, right after an expensive (and extensive) mid-life overhaul. In what is generally seen as a bad political move, more than anything to do with her capabilities.

(more…)

March 6, 2025

HMCS Bonaventure – The Pride of Canada’s Fleet

January 26, 2025

The FAL in Cuba: Left Arm of the Communist World?

Forgotten Weapons

Published 7 Oct 2024The full version of this video, including the fully automatic fire not permitted on YouTube, is available on History of Weapons & War here:

https://forgottenweapons.vhx.tv/video…

In 1958, Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista ordered some 35,000 FAL rifles from FN, including both regular infantry rifles have heavy-barreled FALO light machine guns. Before any of them could arrive, however, Batista fled the country and his guns were delivered to Fidel Castro beginning in July 1959.At this time, the FAL was still a fairly new rifle, having been first adopted by Venezuela in 1954 and Belgium in 1954/55. A few changes had been made by the time of the Cuban contract (like the slightly taller sights requested by the Germans), but these were still Type 1 receivers with early features.

The first consignment of rifles arrived from Belgium to Havana July 9, 1959 and this consisted of 8,000 rifles and ten LMGs. A second shipment of 2,000 rifles arrived October 15th, and a third of 2,500 rifles and 500 LMGs on December 1st. The final ship bringing FALs to Cuba (the French freighter La Courbe) docked in Havana March 4th 1960, and suffered a pair of explosions while bring unloaded. Several hundred people were killed or injured, and Castro blamed the CIA for the event. In total, the Cubans received 12,500 FAL rifles and 510 FALO light machine guns.

The FALs were used, but many ended up being exported to other parties, as Cuba generally moved to Soviet bloc small arms starting in 1960 (when they began receiving weapons from the USSR and Czechoslovakia). These were often scrubbed of their Cuban markings before shipment, and can be found with a round hole milled in the magazine well where the Cuban crest originally was, similar to how some South African FALs were scrubbed before being sent to Rhodesia.

Thanks to Sellier & Bellot for giving me access to this pair of very scarce Cuban FALs to film for you!

(more…)

December 9, 2024

Public wash-house Liverpool (1959) | BFI National Archive

BFI

Published Dec 12, 2017Admire the industriousness of the Liverpool women who transport huge bundles of laundry to and from the local wash-house every week, crammed into old prams or balanced skilfully on their heads. The wash-house doubles as a social hub for the women, with a cafe and creche facilities. At the time of filming, this one in the Pontack Lane area was one of 13 remaining original public wash-houses in the city, although new more modernised buildings were under construction. Liverpool’s last working wash-house closed in 1995.

The peppy documentary not only looks at the modern wash-house, but introduces the story of Kitty Wilkinson, “the Saint of the Slums”, who pioneered the public wash-house movement in Liverpool during the 1832 cholera epidemic. John Abbot Productions, who made the film, specialised in sponsored non-fiction films from the late 1950s to the late 1970s.

(more…)

November 2, 2024

The Short SA.4 Sperrin; Britain’s Back-Up, Back-up Nuclear Bomber

Ed Nash’s Military Matters

Published Jul 9, 2024No, I have no idea how you pronounce “Gyron”.

August 4, 2024

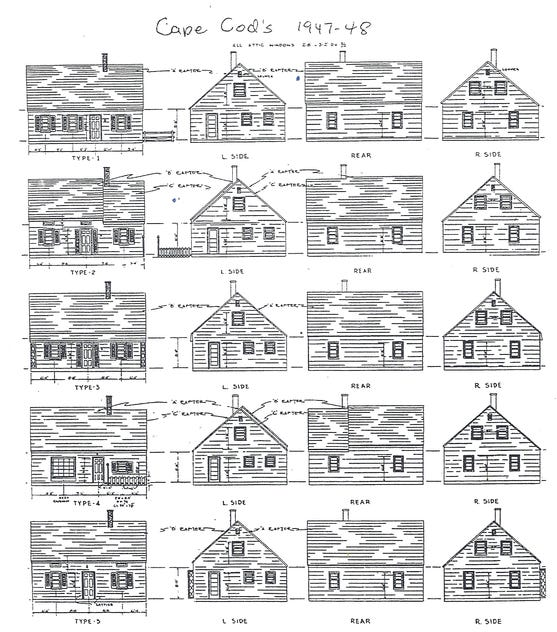

The rise and (rapid) fall of the Levittown model

Virginia Postrel linked to this interesting post at Construction Physics which traces the brief heyday of William Levitt’s “Levittown” model for mass-producing modern housing:

For decades, people have tried to bring mass production methods to housing: to build houses the way we build cars. While no one has succeeded, arguably the man that came closest to becoming “the Henry Ford of homebuilding” was William Levitt, with his company Levitt and Sons. Levitt is most famous for building “Levittowns”, developments of thousands of homes built rapidly in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. By optimizing the construction process with improvements like standardized products and reverse assembly line techniques, Levitt and Sons was able to complete dozens of homes a day at what it claimed was a far lower cost than its competitors. William Levitt styled his company as the General Motors of housing, and both he and it became famous. Levitt graced the cover of Time magazine in 1950, and Levittowns became a household name.

For a time, it appeared that Levitt might actually sweep away the old way of building and become the Henry Ford of housing through modern mass production techniques. Levitt boasted that he could build more cheaply than anyone else, and for decades Levitt and Sons was the largest homebuilder in the U.S., and probably the world.1 But Levitt’s success unraveled. By the late 1970s, Levitt and Sons had barely escaped bankruptcy, and it emerged as a small, conventional homebuilder, which it would remain until it went out of business for good in 2018. Levitt himself would leave Levitt and Sons in the early 1970s, lose his fortune after a series of failed development projects in the U.S. and abroad, and die penniless in 1994.

Levitt’s model of large-scale, efficient homebuilding using mass production-style methods worked for a brief window in the 1950s, but by the end of the 1960s a changing housing market and increasingly strict land use controls meant that such methods were no longer feasible. And even at its peak, Levitt likely pushed large-scale building beyond what could be justified on pure economic terms. Levittown was ultimately a response to a temporary set of housing market conditions, not the herald of a new, better way of building.

[…]

At Levittown, the construction process was broken down into 26 separate steps, each performed by a separate crew. Crews would go to a house, perform their required task (using material that had been pre-delivered), then move on to the next house. Within the crew, work was further specialized: on the washing machine installation crew, William Levitt noted that “one man did nothing but fix bolts into the floor, another followed to attach the machine”, and so on. By breaking down the process into repetitive, well-defined steps, workers didn’t have to spend time figuring out what they should do (what Levitt described as “fumbling and figuring”).

In addition to task and product standardization, Levitt and Sons took advantage of machines and mechanization wherever possible. It had its own cement trucks, and operated its own foundation-digging machinery and cinder block-making machinery. Levitt and Sons was an early user of power tools like paint sprayers, power saws, routers, and nailers. The company also made extensive use of what at the time were relatively novel factory-produced materials, like plywood and drywall.

Like any mass production process, the ultimate enemy of building Levittown was delay: keeping construction on track meant a steady, uninterrupted stream of material that arrived at the jobsite exactly when needed. On a typical construction site, as much as half the time was wasted while workers wandered around looking for needed material. In Levitt’s operation, wasted time was close to zero. To ensure timely material deliveries (and to cut out middlemen), Levitt and Sons had its own distribution company, the North Shore Supply Company, which stretched for half a mile along a railroad stop near the jobsite. To avoid delays, North Shore Supply kept a sufficient supply of material on-hand to build 75 houses, and pre-assembled items like plumbing trees, stairs, and cabinets. North Shore was also where lumber was pre-cut to the correct size. By using standardized designs, planned work sequences, and carefully controlled precutting, Levitt and Sons was able to almost entirely eliminate rework during the construction process.

But assuring an uninterrupted flow of material required far more than just owning a distribution company. William Levitt described some of the extreme measures the company went to avoid delays or slowdowns:

We wouldn’t let ourselves be stopped by shortages. When cement was unavailable in this country we chartered a boat and brought it in from Europe. When lumber was in short supply, we bought a forest in California and built a mill. When nails were hard to come by, we set up a factory in our backyard and made them ourselves.

At its peak Levitt and Sons was completing 36 homes in Levittown a day. And the huge backlog of demand meant that housing was sold quickly. Months before the first Levittown homes were completed, families stood in line for the opportunity to rent one (roughly the first 2,000 Levittown homes were built as rentals). On a single day in 1949, Levitt and Sons sold 1400 homes, some to families who had been waiting in line for days. At $7,990 for a 800 square foot home, Levitt boasted that he could sell his houses for $1,500 less than the competition and still make $1,000 in profit.2

[…]

William Levitt tried harder than anyone else to make housing mass producing happen, and for a brief moment it looked like he might succeed. But Levitt’s dreams were predicated on a particular set of housing market conditions — a huge backlog of demand, relatively few competitors, compliant building jurisdictions and little public opposition — that quickly dissipated. In The Merchant Builders, Ned Eichler notes that as early as the mid-1950s, the Levitt model of a single, enormous project built rapidly with mass production-style methods no longer made sense. Says Eichler, “There simply was no market in which an appropriate site could be bought cheaply enough or in which demand was great enough to sustain such a pace”. Many of Levitt’s innovations — slabs instead of basements, power tools, drywall and plywood — did not require large volume production, and were adopted by other, smaller builders (and have since become standard). The enormous increase in land use controls starting in the late 1960s only further inhibited the sort of large-scale developments that Levitt favored.

1. Levitt and Sons was at least the largest in the U.S. in 1950, and was in 1968 when it was acquired by ITT, and probably for some years after that.

2. The first Levittown demonstration homes were sold for $6,990.

July 31, 2024

The History of the British Rail Symbol

Jago Hazzard

Published Apr 21, 2024Moving forward or indecision?

July 19, 2024

Airline Food During the Golden Age of Air Travel

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Apr 9, 2024Back before airlines could compete with lower prices, they competed with the quality of atmosphere, service, and, of course, food.

I’d be happy to have this pot roast on the ground, let alone on an airplane. The meat is so tender that it falls apart, the vegetables and herbs give it wonderful flavor, and you get the added bonus of it making your house smell awesome as it simmers.

(more…)

July 16, 2024

This Jet Age – Farnborough Airshow, 1953

spottydog4477

Published Dec 25, 2009

June 20, 2024

QotD: Canadian soldiers of the 1950s and early 1960s

In the field in summer, [Canadian] soldiers wore bush clothes, which were adequate enough, though multi-hued depending on how often they had been washed. There were no winter field uniforms, and soldiers wore U.S. Army field jackets. On exercises, black coveralls were the usual dress, the sloppiest uniform in any army at the time. Until the army introduced combat clothing in the mid-1960s, Canadian soldiers looked as though they had been kitted out by a second-hand clothing store.

J.L. Granatstein, Canada’s Army, 2002.

June 17, 2024

5 Foods that Changed Fast Food Forever (ft. @mythicalkitchen)

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Mar 8, 2024The Mythical Kitchen Cookbook by Josh Scherer: https://amzn.to/49Se1qZ

June 5, 2024

Hollywood has been here before … and they learned nothing

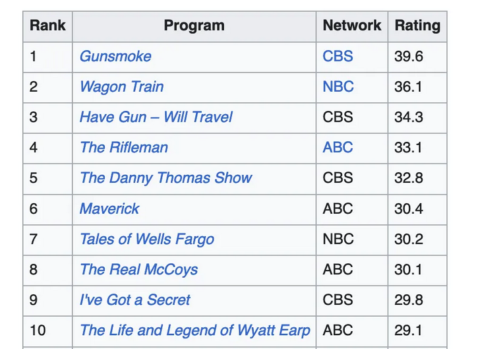

Ted Gioia illustrates the mind-blowing dominance of westerns on TV and in the theatre in the 1950s and how quickly the boom was over and has never come close to recovering:

Source – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Top-rated_United_States_television_programs_of_1958%E2%80%9359

Eight of the top ten shows during the 1958-59 season were westerns.

Spaceships were in the news every day back then, but on TV it was just horses — and occasionally a covered wagon. Each of the three networks was caught up in a time warp, partying like it was 1899.

Any fool could see that they were saturating the market. Yet the studios kept launching new westerns with regularity, although with less confidence, for another decade, more or less.

Back in 1955, the three US TV networks had introduced three new western-themed series — Gunsmoke, Cheyenne, and Wyatt Earp. But two years later, the networks ramped up their investment in cowboys, launching nine new westerns that fall.

And it got worse.

In 1958, these three networks introduced ten more western series. On some nights, you could watch cowboys for two hours straight on ABC. CBS and NBC also started scheduling back-to-back Wild West shows.

I need to stress that the western was already an exhausted genre long before 1960. Movie theaters had relied on cowboys as an audience draw going back at least to Broncho Billy Anderson and The Great Train Robbery (1903).

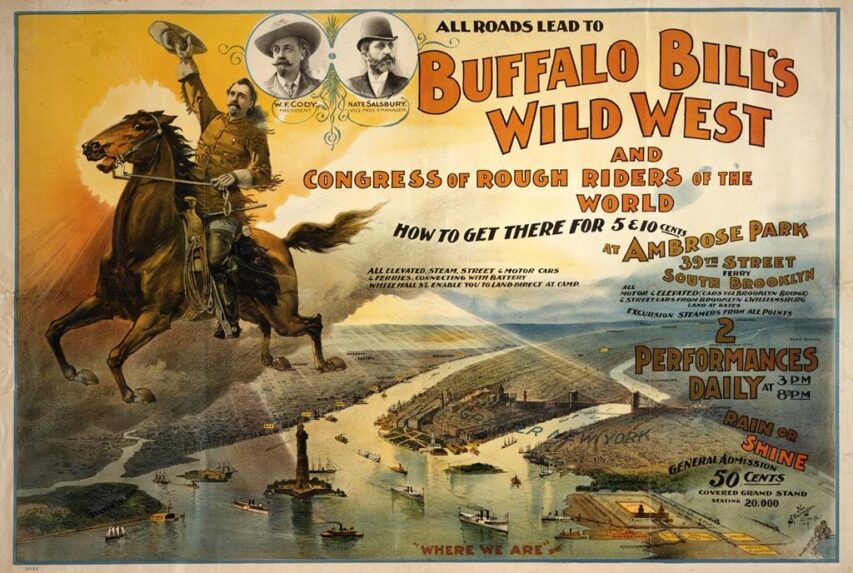

And cheap books and magazines with stories of the Wild West had already been around for decades at that point. By my measure, nostalgia for the old West dates back to the launch of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show on May 19, 1883 in Omaha, Nebraska — four years after the invention of the gasoline engine.

[…]

Younger viewers were the first to abandon the western — a telling sign, especially when you consider that, back in the 1930s, children and teens had been the core audience for the genre.

By the time Gunsmoke went off the air in 1975, the few remaining fans were old-timers — maybe the same ones who had gone to movie theaters to cheer for Roy Rogers in the 1930s. That show had been the most popular TV series in the US for four seasons in the late 1950s. But a cowboy series would never do that again.

Youngsters lost interest in westerns despite a proliferation of merchandise. During my childhood, I paid no attention to the cowboy genre — nor did any of my friends. But brand merchandise was everywhere. We could buy Gunsmoke comic books, trading cards, lunchboxes, and — of course! — toy guns, among other paraphernalia.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that these products did not develop the market — they merely saturated it.

May 14, 2024

Spirit Duplicators: Copies Never Smelled So Good

Our Own Devices

Published Feb 7, 2024Widely used throughout the 20th Century by schools, churches, fan clubs, and other small organizations, Spirit Duplicators or “Ditto” machines allowed small runs of documents to be copied cheaply and quickly. Often conflated with mimeographs, they were in fact a distinct technology, used a master sheet printed with dye-bearing wax instead of liquid ink. Paper passing through the machine was wetted with a solvent and pressed against the master sheet, causing some of the dyed wax to dissolve and transfer onto the paper.

0:00 Introduction

1:26 “Ditto” and “Banda” as Genericized Trademarks

2:15 Rex Rotary R11 – History

2:56 Rex Rotary R11 – External Controls

3:17 Creating Master Sheets

4:44 Correcting Master Sheets

5:21 Loading the Master Sheet

6:00 Solvent (“Duplicator Fluid”) System

7:35 Loading Paper/Final Setup

8:31 Making Copies

9:05 Other Design Features / Internal Mechanism

9:52 Design Variations

10:12 Master Sheet Variations

11:00 Impact of Spirit Duplicators

11:23 Outro

(more…)

May 5, 2024

M98kF1 ZF41: Norway Recycles Germany’s Worst Sniper Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 29, 2024When Germany capitulated at the end of World War Two, several hundred thousand German soldiers were stuck in Norway (thanks to the efforts of the Norwegian Resistance preventing them from moving south to reinforce against Allied landings in Normandy). These solders’ arms were surrendered to the Norwegians, and they formed the basis of Norwegian Army and Home Guard armaments for many years. With hundreds of thousands of K98k rifles to choose from, the Norwegians were able to pick out plenty in good condition. This included 400 ZF41 DMR/sniper rifles that were kept intact and taken into Norwegian service. Three different branches used the rifles, and they are marked on the chamber with either HAER (Army), FLY (Air Force), or K.ART (Naval Artillery).

In 1950, Norway began to get US military aid in .30-06, and they decided to rebarrel these Mausers to that cartridge. The process began in 1952 and they were all converted by the end of 1956. The new barrels are marked “KAL 7.62”, for 7.62x63mm. There was only a small amount of experimental further conversion to 7.62mm NATO. The ZF-41 models like this one were also given a new serial number tag riveted onto the scope mount with the rifle’s serial number (150001 through 150400).

Converted Mausers served in the Home Guard until the early 1970s, when they were replaced by the AG3 (HK91).

(more…)

April 27, 2024

Floating Fun: The History of the Amphibious Boat Car

Ed’s Auto Reviews

Published Aug 9, 2023A classic car connoisseur dives into the general history of amphibious cars and vehicles. When did people start to build boat-car crossovers? What made Hans Trippel’s Amphicar 770 and the Gibbs Aquada so special? And why don’t you see a lot of amphibious automobiles out on the road and water these days?

(more…)

April 23, 2024

The 1950 Marketing Contest to Name the S&W Chiefs Special

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 19, 2024Today we’re taking a look at a Smith & Wesson Chiefs Special, but not just any Chiefs Special. This is serial number 29, factory engraved and gifted to Chief Edward Boyko of Passaic New Jersey in 1950. When S&W introduced the new revolver to compete with Colt’s Detective Special, they simply called it the “Model J” (it was the first of the J-frame S&W revolvers). They released it at the 1950 annual conference of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, and ran a contest among to attendees to name the new gun.

Chief Edward Boyko’s suggestion of “Chiefs Special” was (perhaps unsurprisingly, given the audience) voted winner, and S&W gave him a personally engraved example as a prize. He would carry that gun for another 10 years as Passaic Chief of Police before retiring in 1960.

The Chiefs Special was essentially a slightly scaled-up I-frame revolver, strengthened to handle the .38 Special cartridge instead of the previous .38 S&W option. This extremely early example has a number of features not present on standard production guns, including the small trigger guard, large cylinder release latch, and semi-circular front sight.

(more…)