I do not take selfies, but (if I am to tell the truth) it is not because I am appalled at the vacuity doing so seems to require, or at least to call forth: Sheep in a field are more like Rodin’s Thinker than are people who hold their phones on those ridiculous sticks before their faces. No, the problem is that, where the camera and I are concerned, it is not that it never lies, but that it never tells the truth.

I am always appalled by its results. I do not look like that when I glance in the mirror: I look far younger, less bald, wrinkled, ugly in short. I conclude, of course, that I lack that mysterious quality that only some lucky people have: I am not photogenic. If the camera never lied, if it showed me as I truly am, I would come out much better in photos.

I think it was the French-Romanian writer Emil Cioran who said that if a man knew that someone would one day write a biography of him, he would cease to live; in other words, it would paralyze him. In like fashion, if I thought that people would photograph me, I would stay indoors — the millions of spy cameras everywhere don’t count, no one looks at what they have recorded until there has been a murder or a terrorist attack (and then everyone is mostly unrecognizable).

I conclude, therefore, that most people who take selfies are at least minimally satisfied with their appearance, however they may appear to others. But in fact it hardly requires reflection on the selfie as a social, or antisocial, phenomenon to know that very large numbers of people have no idea what they look like to others. Or perhaps it is simply that they don’t care.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Suit Yourselfie”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-09-16.

February 2, 2023

QotD: “Selfies”

February 1, 2023

Changing views of Gandhi

In UnHerd, Pratinav Anil recounts some of the changes to Gandhi’s reputation and place in Indian public memory:

Gandhi, poor fellow, had his ashes stolen on the 150th anniversary of his birth. “Traitor”, scrawled the Hindu supremacist malcontents on a life-size cut-out of the Mahatma at the mausoleum. That was a couple of years ago, but it’s a sentiment that’s grown shriller since. Unsurprisingly. In government as in schools, in newsrooms as on social media, the founding father’s defenders are being put out of business by his detractors. His Congress Party, after 50 years of near-uninterrupted rule since independence in 1947, is now in ruins, upstaged by the Bharatiya Janata Party. Hindu supremacists have stolen the show, while India’s Muslims, Christians, and Dalits are persecuted. With the changing of the guard, Gandhi’s extravagant ideal — unity in diversity — has gone the way of his ashes.

His reputation, too, is in tatters. Last year, the National Theatre staged a play about his assassination. But The Father and the Assassin centred not on Gandhi but Godse, the man who killed him 75 years ago this week. Here is a tender portrait of a tortured soul, a blushing boy raised as a girl to propitiate the gods who had taken away his three brothers, who becomes radicalised and blames Gandhi for betraying Hindus and mollycoddling Muslims, so causing Partition. It is no accident that Godse was a card-carrying Hindu supremacist, a member of the parent organisation of the BJP, to which India’s new ruler Narendra Modi belongs. Today, statues of Godse are going up across the country just as statues of Gandhi are being pulled down across the world.

Needless to say, this is a most disturbing development. Yet the reaction of liberals, Indian as well as Western, has been no less troubling. An unthinking anti-imperialism of old has joined up with an unthinking anti-Hindu supremacism of new to beget a bastardised Gandhi. What we have is not a creature of flesh and blood, possibly a great if also flawed man, but rather a deified hero. This is the Gandhi with a saintly halo around him who greets you from Indian billboards, grins at you from rupee notes, stares down at you from his plinth on Westminster’s Parliament Square, and, in Ben Kingsley’s portrayal of him, slathered in a thick impasto of fake tan, moves you to a standing ovation.

This is the easily comestible fortune-cookie Gandhi you encounter in airport bestsellers such as Ramachandra Guha’s double-decker hagiography, and also the sartorial icon whose wire-rim glasses were emulated by Steve Jobs. There is the Gandhi of the gags, most famous for a retort he probably never made: asked what he thought of Western civilisation, the Mahatma is reported to have replied: “I think it would be a good idea.” Ba-dum ching! Then there’s the Christological Gandhi, a modern messiah turning the other cheek: “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.” There’s also Gandhi the self-help guru: “Be the change that you wish to see in the world.” One could go on.

Here’s where the historian in me says, would that it were so simple. Gandhi was no liberal. And if those who sing his praises today knew a little more about Gandhi the man, rather than Gandhi the saint, their adulation would very quickly dry up. The fact is that the Mahatma hasn’t aged well. He detested democracy, defended the caste system, and had a deeply disturbing relationship with sex.

None of this should surprise us. Unlike some of the more cerebral thinkers of his cohort, figures such as Ambedkar and Periyar, Gandhi possessed a shallow mind. The product of a rather parochial education, admittedly the best that could be bought in turn-of-the-century western India, he struggled to juggle academic and conjugal demands. His precocious marriage to Kasturbai at 13 was a misalliance, perennially troubled by his suspicions of her infidelity. Not the sharpest knife in the drawer, he dropped out of Samaldas College. It was only in London, where he went to read law, that his horizons widened.

Then again, not for the better.

Surviving on Leather

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 31 Jan 2023

(more…)

It’s the job of the music critic to be loudly and confidently wrong as often as possible

Ted Gioia points out that a lot of musical criticism does not pass the test of time … and sometimes it’s shown to be wrong before the ink is dry:

When I was in my twenties, I embarked on writing an in-depth history of West Coast jazz. At that juncture in my life, it was the biggest project I’d ever tackled. Just gathering the research materials took several years.

There was no Internet back then, and so I had to spend weeks and months in various libraries going through old newspapers and magazines — sometimes on microfilm (a cursed format I hope has disappeared from the face of the earth), and occasionally with physical copies.

At one juncture, I went page-by-page through hundreds of old issues of Downbeat magazine, the leading American jazz periodical founded back in 1934. And I couldn’t believe what I was reading. Again and again, the most important jazz recordings — cherished classics nowadays — were savagely attacked or smugly dismissed at the time of their initial release.

The opinions not only were wrong-headed, but they repeatedly served up exactly the opposite opinion of posterity.

Back in my twenties, I was dumbfounded by this.

I considered music critics as experts, and hoped to learn from them. But now I saw how often they got things wrong — and not just by a wee bit. They were completely off the mark.

Nowadays, this doesn’t surprise me at all. I’m painfully aware of all the compromised agendas at work in reviews — writers trying to please an editor, or impress other critics, or take a fashionable pose, or curry favor with the tenure committee, or whatever. But there is also something deeper at play in these huge historical mistakes in critical judgments, and I want to get to the bottom of it.

Let’s consider the case of the Beatles.

On the 50th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the New York Times bravely reprinted the original review that ran in the newspaper on June 18, 1967. I commend the courage of the decision-makers who were willing to make Gray Lady look so silly. But it was a wise move — if only because readers deserve a reminder of how wrong critics can be.

“Like an over-attended child, ‘Sergeant Pepper’ is spoiled,” critic Richard Goldstein announced. And he had a long list of complaints. The album was just a pastiche, and “reeks of horns and harps, harmonica quartets, assorted animal noises and a 91-piece orchestra”. He mocks the lyrics as “dismal and dull”. Above all the album fails due to an “obsession with production, coupled with a surprising shoddiness in composition”. This flaw doesn’t just destroy the occasional song, but “permeates the entire album”.

Goldstein has many other criticisms — he gripes about dissonance, reverb, echo, electronic meandering, etc. He concludes by branding the entire record as an “undistinguished collection of work”, and even attacks the famous Sgt. Pepper’s cover — lauded today as one of the most creative album designs of all time — as “busy, hip, and cluttered”.

The bottom line, according to the newspaper of record: “There is nothing beautiful on ‘Sergeant Pepper’. Nothing is real and there is nothing to get hung about.”

How could he get it so wrong?

What’s the Greatest Machine of the 1980s … the FV107 Scimitar?

Engine Porn

Published 19 Jan 2015Light, agile and very fast on all types of terrain, the fabulous Scimitar FV107 armoured reconnaissance vehicle was developed by car manufacturer Alvis, who were asked to build a fast military vehicle that was light enough to be airdropped — simply not an option for full sized battle tanks at the time, which averaged around 13 tonnes. [NR: I think they mean “light tanks” here, as MBTs of the era would have been more like 50+ tons.]

Alvis got the weight down to under 8 tonnes by using a new type of aluminium alloy and minimising armour rating in favour of speed. They built the Scimitar around a 220 horsepower, six cylinder, 4.2 litre Jaguar sports car engine with ground-breaking transmission that allowed differential power to each set of tracks. The result was a sports car of the the military world that might not be the toughest in the field, but could race its way out of trouble at speeds of up to 70 miles an hour.

What makes it great: A revolutionary armoured vehicle that brought the very best of British sports car performance to the battlefield.

Time Warp: The Scimitar was the only armoured vehicle to be used by the British Army in the Falklands War.

This short film features Chris Barrie taking the Scimitar for a spin.

(more…)

QotD: Creating a hostile working environment

I can honestly say that in my 40+ years in business life, I never saw a man who could compete with any woman in creating an atmosphere of devious backbiting, career assassination and downright unpleasantness in the workplace. And in most cases it had nothing to do with crap like sexual harassment, either (although I saw that little ploy used quite often). Women were (and are) just as willing to stab other women in the back, if it benefits them — or sometimes just out of outright spite.

Anecdote is not data, of course; but ask any ordinary working woman* whether she’d prefer to work with men, or in a female-only workplace. The response may surprise you.

* This definition would exclude gender careerists and almost all rabid feministicals.

Kim du Toit, “Just Sayin'”, Splendid Isolation, 2022-10-26.

January 31, 2023

The Allied Flying Aces of World War Two – Documentary Special

World War Two

Published 30 Jan 2023Young, daring, and handsome, the Allied fighter aces of World War Two have captivated the public with their thrilling exploits. Join us as we take a look at the top scorers! Thanks to Curiosity Stream for sponsoring today’s video.

(more…)

Workshop Tour | Paul Sellers

Paul Sellers

Published 23 Sept 2022Many of you would have seen Paul go from working in a castle to reducing his workspace and ending up working in a single-car garage. This workshop has evolved over the years and is constantly adapting to Paul’s way of working.

Come and look around the workshop as Paul shows you what his shop entails and how it all aids him with his hand tool woodworking.

——————

(more…)

QotD: Religious rituals

I want to start with a key observation, without which much of the rest of this will not make much sense: rituals are supposed to be effective. Let me explain what that means.

We tend to have an almost anthropological view of rituals, even ones we still practice: we see them in terms of their social function or psychological impact. Frank Herbert’s Children of Dune (the Sci-fi miniseries; I can’t find the quote in the text, but then it’s a lot of text) put it wonderfully, “Ritual is the whip by which men are enlightened.” That is, ritual’s primary effect is the change that takes place in our minds, rather than in the spiritual world. This is the same line of thinking whereby a Church service is justified because it “creates a sense of community” or “brings believers together”. We view rituals often like plays or concerts, experiences without any broader consequences beyond the experience of participation or viewing itself.

This is not how polytheism (ancient or modern) works (indeed, it is not how most modern Christianity works: the sacraments are supposed to be spiritually effective; that is, if properly carried out, they do things beyond just making us feel better. You can see this articulated clearly in some traditional prayers, like the Prayer of Humble Access or Luther’s Flood Prayer).

Instead, religious rituals are meant to have (and will have, so the believer believes, if everything is done properly) real effects in both the spiritual world and the physical world. That is, your ritual will first effect a change in the god (making them better disposed to you) and second that will effect a change in the physical world we inhabit (as the god’s power is deployed in your favor).

But to reiterate, because this is key: the purpose of ritual (in ancient, polytheistic religious systems) is to produce a concrete, earthly result. It is not to improve our mood or morals, but to make crops grow, rain fall, armies win battles, business deals turn out well, ships sail, winds blow. While some rituals in these religions do concern themselves with the afterlife or other seemingly purely spiritual concerns (the lines between earthly and spiritual in those cases are – as we’ll see, somewhat blurrier in these religions than we often think them to be now), the great majority of rituals are squarely focused on what is happening around us, and are performed because they do something.

This is the practical side of practical knowledge; the ritual in polytheistic religion does not (usually) alter you in some way – it alters the world (spiritual and physical) around you in some way. Consequently, ritual is employed as a tool – this problem is solved by a wrench, that problem by a hammer, and this other problem by a ritual. Some rituals are preventative maintenance (say, we regularly observe this ritual so this god is always well disposed to us, so that they do X, Y, and Z on the regular), others are a response to crisis, but they are all tools to shape the world (again, physical and spiritual) around us. If a ritual carries a moral duty, it is only because (we’ll get to this a bit more later) other people in your community are counting on you to do it; it is a moral duty the same way that, as an accountant, not embezzling money is a moral duty. Failure lets other people (not yourself and not even really the gods) down.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part II: Practice”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-11-01.

January 30, 2023

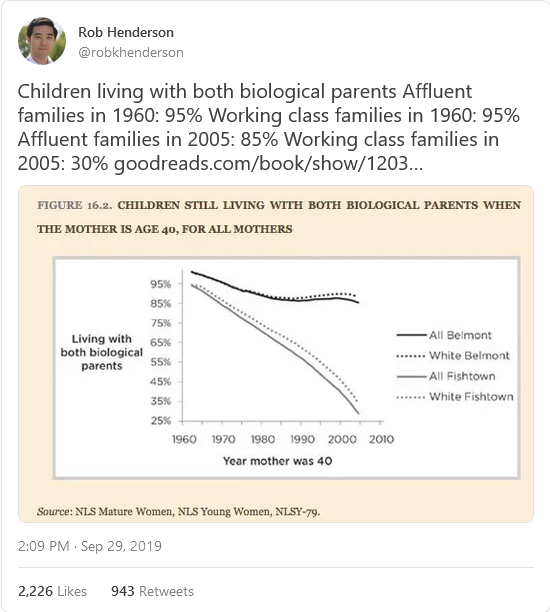

Crime on Toronto’s public transit system is merely a symptom of a wider social problem

As posted the other day, Matt Gurney’s dispiriting experiences on an ordinary ride on the TTC are perhaps leading indicators of much wider issues in all of western society:

“Toronto subway new train” by BeyondDC is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 .

Caveats abound. Toronto is, relatively speaking, still a safe city. The TTC moves many millions of people a week; a large percentage of whom are not being knifed, shot or burnt alive. And so on. We at The Line also suspect that whatever is happening in Toronto isn’t happening only in Toronto, but Toronto’s scale (and the huge scope of the TTC specifically) might be gathering in one place a series of incidents that would be reported as unconnected random crimes in any other city. A few muggings in Montreal or Winnipeg above the usual baseline for such crimes won’t fit the media’s love of patterns as much as a similar number of incidents on a streetcar or subway line.

Fair enough, duly noted, and all that jazz.

But what is happening out there?

Your Line editors have theories, and we’ve never hesitated to share them before: we think the pandemic has driven a portion of the population bonkers. We’d go further and say that we think it has left all of us, every last one, less stable, less patient, less calm and less empathetic. For the vast majority of us, this will manifest itself in many unpleasant but ultimately harmless ways. We’ll be more short-tempered. Less jovial at a party. Less patient with strangers, or even with loved ones. Maybe a bit more reclusive.

But what about the relatively small majority of us that were, pre-2020, already on the edge of deeper, more serious problems? What about those who were already experiencing mental-health issues, or living on the edge of real, grinding poverty?

It’s not like the overall societal situation has really improved, right? COVID-19 itself killed tens of thousands, and took a physical toll on many more, but we all suffered the stress and fear not just of the plague, but of the steps taken to mitigate it. (Lockdowns may have been necessary early in the pandemic, but they were never fun or easy, and that societal bill may be coming due.) Since COVID began to abate, rather than a chance to chill out, we’ve had convoys, a war, renewed plausible risk of nuclear war, and now a punishing period of inflation and interest-rate hikes that are putting many into real financial distress. We are coping with all of this while still processing our COVID-era stress and anxiety.

The timing isn’t great, is what we’re saying.

And on the other side of the coin, basically all our societal institutions that we’d turn to to cope with these issues — hospitals, social services, homeless shelters, police forces, private charities, even personal or family support networks — are fried. Just maxed out. We have financial, supply chain and, most critically, human-resource deficits everywhere. The people we have left on the job are exhausted and at their wits’ end.

This leaves us, on balance, less able to handle challenges than we were in 2020, due to literal exhaustion of both institutions and individuals. Meanwhile, against the backdrop of this erosion of our capacity, our challenges have all gotten worse!

It’s not hard to do the mental math on this, friends. It seems to us that in 2020, the policy of Canadian governments from coast to coast to coast, and at every level, was to basically keep a lid on problems like crime, homelessness, housing prices and shortages, mental health and health-care system dysfunction, and probably others we could add. One politician might put a bit more emphasis on some of these issues than others, in line with their partisan priors, but overall, the pre-2020 status quo in Canada was pretty good, and our political class, writ large, basically self-identified as guardians of that status quo, while maybe tinkering a bit at the margins (and declaring themselves progressive heroes for the trouble of the tinkering).

But then COVID-19 happens, and all our problems get worse. And all our ways of dealing with those problems get less effective. It doesn’t have to be by much. Just enough to bend all those flatlined (or maybe slightly improving) trendlines down. Instead of homelessness being kind of frozen in place in the big cities, it starts getting worse, bit at a time, month after month. The mental-health-care and homeless shelter systems that weren’t really doing a great job in 2020, but were more or less keeping big crises at a manageable level, started seeing a few more people fall through the cracks each month, month after month. Those people are just gone, baby, gone.

The health-care system that used to function well enough to keep people reasonably content, if not happy, locks up, and waitlists balloon, and soon we can’t even get kids needed surgeries on time.

The housing shortage goes insane, and prices somehow survive the pandemic basically untouched.

The court system locks up, meaning more and more violent criminals get bail and then re-offend, even killing cops when they should be behind bars.

None of these swings were dramatic. They were all just enough to set us on a course to this, a moment in time where the problems have had years to compound themselves and are now compounding each other.

Here’s the rub, folks. The Line doesn’t believe or accept that any of the problems we face today, alone or in combination, are automatically fatal. We can fix them all. But we need leaders, including both elected officials and bureaucrats, who fundamentally see themselves as problem fixers, and who understand right down deep in their bones that that is what their jobs are, and that they are no longer what they’ve been able to be for generations: hands-off middle managers of stable prosperity.

Eff the WEF | The spiked podcast

spiked

Published 27 Jan 2023Tom Slater, Fraser Myers and Ella Whelan discuss the World Economic Forum, men in women’s prisons and Facebook’s unbanning of Donald Trump. Plus, Timandra Harkness explains the dangers of the UK’s Online Safety Bill.

(more…)

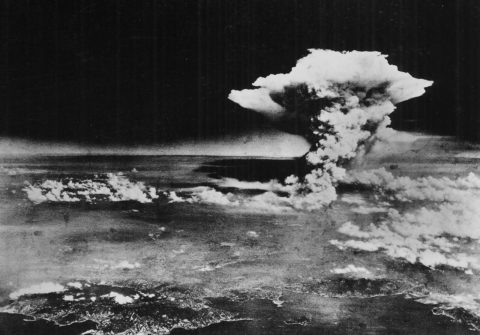

“… say what you want about the good old Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, but at least its crappy clock is behaving like a clock these days”

Colby Cosh congratulates the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists for at least getting their clock moving in the normal direction once again:

Atomic cloud over Hiroshima, taken from “Enola Gay” flying over Matsuyama, Shikoku, 6 August, 1945.

US Army Air Force photo via Wikimedia Commons.

On Tuesday, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (really a foundation that publishes a famous magazine by that name) announced that it would be scooching the minute hand of its renowned “Doomsday Clock” forward. The clock will now read 11:58:30 p.m., midnight minus 90 seconds. The Bulletin does this once a year — at a time, by pure coincidence, when newspaper editors are notoriously starved for copy.

The Doomsday Clock was originally (in 1947) a one-off magazine cover design by Martyl Langsdorf (1917-2013), a landscape artist who was married to one of the Manhattan Project physicists. She happened to set the clock at about seven minutes to midnight, but the visual metaphor was irresistible. As the arms race and nuclear proliferation began, the editors of the Bulletin started rearranging Langsdorf’s clock face as an index of the danger from nuclear exchange.

Even by saying this much I am intruding somewhat on the turf of a colleague, Tristin Hopper, who is eternally preoccupied with the pure stupidity of the Doomsday Clock. As T-Hop never tires of pointing out, you have really lost track of the clock metaphor if you manually wiggle the minute hand backward or forward annually.

Moreover, the face of the clock can at best be considered a lagging indicator. The year 1947 was probably the moment at which the danger of a pre-emptive nuclear strike was greatest. Intellectuals and strategists needed a few years to think through the implications of nuclear weapons: the logic of a first strike was compelling, and might have won the argument in any country that developed nukes until the equilibrium of mutually assured destruction was both established and theorized.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the clock closer to midnight as the world was learning to live with nukes and nuclear proliferation. Eventually the hand was moved backward in 1960 — practically in time for the frightening Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Royal Marines at War: Rough Weather Landing

Royal Marines

Published 31 Aug 2012Rough Weather Landing is a secret film recording of “an experiment by No4 Commando” demonstrating their ability to launch a surprise attack on a seemingly impregnable coastline.

From the comments:

ogdiver

8 years ago

“That’s right lad, you’re going to land from a boat with all the reserve buoyancy of a digestive biscuit onto a rocky shore, in a pounding surf, with a 3″ mortar base plate strapped to your back and tackety boots for swimming. But don’t worry, we’ll give you the the inflated inner tube off an Austin 7 to cling to and we’ll be doing it in daylight for the cameras.” Those blokes were nails.

QotD: Teaching … back in the day

There’s so much truth to this. The “authority figure” thing is especially interesting. As I started in “education” fairly late, I was conspicuously older than most of my graduate school cohort. They had discipline problems in their classes; I never did. This was because I at least looked like an adult, and dressed like one, too. Every other TA was all of three months removed from undergrad, and tried to show up to teach wearing backwards hats and ratty school apparel. The one kid who took my advice and switched to teaching in “business casual” didn’t have a single discipline problem afterward (poor bastard, he no doubt got killed by his peers for “ageism” or something).

Of course, this was so long ago that students used to be unsure how to address me. Most professors had gone “hip” and had students call them by first name, but there were enough crusty old codgers around who insisted on “Dr. So-and-So” that they didn’t assume. After which I started telling them “you can call me whatever you want, but as a general rule life runs smoother if we respect each other’s station. If you know someone has a title, it’s best to use it unless they specifically tell you otherwise, and it’s always good to respect the social distance between yourself and someone who has something you want. So, choose accordingly.” 20 years ago, most of them got it, and addressed me by my title. 15 years ago, I started getting lots of puzzled puppy dog looks (“what’s a ‘social station’?”). 10 years ago, they all just assumed first names were fine, and before I retired I counted myself lucky if I got so much as a “hey dude”.

Meanwhile, as far as the students were concerned, my job went from “trying to teach them something” to “the annoying meat puppet whose presence we have to tolerate until he puts the A+ in the gradebook for record-keeping purposes”.

Severian, responding to a comment on “Movies Made On Mars”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-02-04.