World War Two

Published 30 Sep 2023This week, Operation Market Garden comes to its unsuccessful conclusion, but there’s a lot more going on — the Soviets launch an offensive in the Estonian Archipelago, the Warsaw Uprising is on the ropes, the Allies advance in Italy, the Americans on Peleliu, and Tito and Stalin make plans to clear Yugoslavia of the enemy.

(more…)

October 1, 2023

The End of Market Garden – WW2 – Week 266 – September 30, 1944

September 30, 2023

The Man Who Stole the Atomic Bomb

World War Two

Published 29 Sep 2023In the New Mexico desert, a secret team of scientists is working flat out to develop atomic bombs. It’s the most important American military project in history. But one of those scientists lives a double life. Klaus Fuchs has decided to betray his country and share America’s most secret technology with the Soviet Union. But is he the only person who has turned traitor?

(more…)

Why did the North Africa Campaign Matter in WW2?

The Intel Report

Published 8 Jun 2023As Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps rolled into Egypt in 1942, the only thing standing between them and Cairo and the Suez Canal was the British 8th Army. In this video we look at what was at stake for both sides, and why the North African campaign made a crucial impact on the outcome of the Second World War.

(more…)

September 29, 2023

WW2 Jet Engine Development

World War Two

Published 28 Sep 2023Jet planes and jet engine technology revolutionized air travel, as we are all well aware. However, the development of jet planes during WW2 was fraught with all sorts of obstacles and hurdles. Let’s take a look at it.

(more…)

September 27, 2023

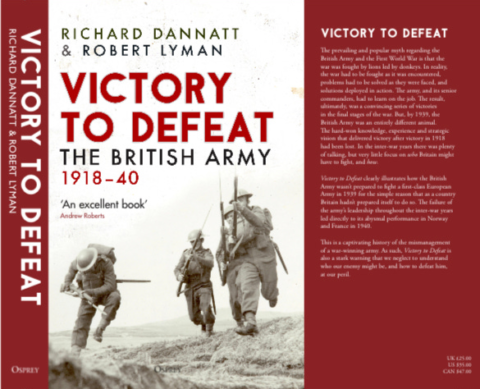

The British army between 1918 and 1940

Richard Dannatt and Robert Lyman recently published Victory to Defeat, which chronicles the decline of the British army’s fighting capabilities in the interwar years. Robert Lyman posted a longer version of Gordon Corrigan’s review for Aspects of History (with permission):

The British Army ended the First World War well trained, well led, well equipped and capable of engaging in all arms intensive warfare. Of all the players, on both sides, this army was unquestionably the most capable of deployment against a first class enemy anywhere in the world. Twenty years later it found itself with very much the same equipment, but with very much less of it, and devoid of either the ability or the means to fight a war in Europe against an enemy which had absorbed the lessons of 1918 but which the British had forgotten. It was the British Army that had invented blitzkrieg (although of course they did not call it that, a term coined by the French press very much later) and used it during the Battle of Amiens and on into the “Hundred Days” that saw the defeat of the German Army on the battlefield, and whatever German myth later averred, it was the British Army that forced that victory on the Western Front, not the French and not the Americans. And yet, in 1939 and 1940 the British were roundly defeated in France and Belgium, in Greece, in Crete and in North Africa. In this important – and to this reviewer almost heart rending – book the authors describe how and why the victors of 1918 were allowed to become incapable of fighting intensive warfare a mere two decades later.

In the first part of the book the authors describe the build up to the First War, and their explanation of the so called “Curragh Mutiny” is much more accurate than many accounts by others (although the officers did not threaten to disobey orders, only to resign, and while Carson’s Ulster Volunteers were indeed incorporated into the British Army as the 36th Ulster Division, so were Redmond’s National Volunteers, into the 16th Irish Division). The authors then go on to show how the British government had, albeit reluctantly, accepted a continental commitment in 1914 and had despatched an expeditionary force to Belgium, described then and later as the finest body of troops ever to leave these shores. Fine they certainly were, well trained, well led and well equipped, but the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of professional regular soldiers was pitifully small, and with experience of imperial policing and not of war against a first class enemy. With the need to expand enormously and rapidly, this army had to adapt to a theatre where massed artillery, machine guns and barbed wire made any attempt to manoeuvre almost impossible. The book shows how by trial and error, by analysis of operations and by a gradually developing doctrine the British learned to use a combination of all arms to break through German defences and eventually to defeat them. With the infantry, the artillery, the armour, the engineers and increasingly the air all working together to get inside the enemy’s decision making circle, to get him on the back foot and keep him there, these were the elements of blitzkrieg, but it was the defeated Germans who were to absorb those principles and perfect them until twenty years after their defeat they were the most competent army in Europe.

After an excellent account of the British journey from an imperial gendarmerie to a practitioner of intensive war, the next part of the book shows how and why by the time the Second World War came along the British were incapable, not only of deterring war, but of fighting it. The “ten year rule”; the reluctance of governments to spend on defence; the political refusal to contemplate another war in Europe and the reluctance of the public to contemplate another bloodletting like that of the First War; the inability to experiment or to develop tanks and armoured vehicles; the seeming impossibility of reconciling the twin requirements of imperial policing and any commitment to land operations in Europe with the assets available; the myth of the “bomber will always get through” and the absence of any consistent war fighting doctrine, all are lucidly explained. Much of the fault is shown to lie with politicians, and surely the most disgraceful example of political interference was the sacking of the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), the professional head of the army, by the leaving of a note on his desk by the very dubious Secretary of State for War, Hore-Belisha. The generals are not spared, however. Despite restrictions on funding and refusal by governments to accept that another war was looming generals could have spoken out, although it does have to be recognised that in a democracy the civil power is paramount.

September 26, 2023

Postwar Warsaw became beautiful, but postwar Coventry became a modernist eyesore

Ed West’s Wrong Side of History remembers how the devastation of Warsaw during World War 2 was replaced by as true a copy as the Poles could manage, while Coventry — a by-word for urban destruction in Britain — became a plaything in the hands of urban planners:

Stare Miasto w Warszawie po wojnie (Old Town in Warsaw after the war)

Polish Press Agency via Wikimedia Commons.

Fifteen months after its Jewish ghetto rose up in a last ditch attempt to avoid annihilation, the people of the city carried out one final act of defiance against Nazi occupation in August 1944.

The Soviets, having helped to start the war in 1939 with the fourth partition of Poland, deliberately halted their advance and refused to help the city in its torment. Without Russian cooperation, the western allies could do little more than an airlift of weapons and supplies, which was doomed to failure.

The Polish Army and resistance fought bravely – some 20,000 Germans were killed or wounded – but at huge cost. As many as 200,000 Poles, most civilians, were killed in the battle and over 80% of the city destroyed – worse destruction than Hiroshima or Nagasaki. And so the Nazis had carried out their plan to erase the Polish capital — yet this was something the Poles refused to accept, even after 1944

Today the Old Town is as beautiful as it ever was, and visitors from around the world come to walk its streets – witnesses to perhaps the most remarkable ever story of urban rebirth.

With the city a pile of rubble and corpses, the post-war communist authorities considered moving the capital elsewhere, and some suggested that the remains of Warsaw be left as a memorial to war, but the civic leaders insisted otherwise – the city would rise again

Warsaw was fought over, bombed, shelled, invaded and twice was the epicentre of brutal urban guerilla warfare, leaving the city in literal ruins. Coventry, on the other hand, wasn’t bombed by the Luftwaffe until 1940 — but the damage had already began at the hands of the urban planners:

Broadgate in Coventry city centre following the Coventry Blitz of 14/15 November 1940. The burnt out shell of the Owen Owen department store (which had only opened in 1937) overlooks a scene of devastation.

War Office photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The attack was devastating, to the local people and the national psyche, and local historian W.G. Hoskins wrote that “For English people, at least, the word Coventry has had a special sound ever since that night”. Yet Coventry also became a byword for how to not to rebuild a city – indeed the city authorities even saw the Blitz as an opportunity to remake the city in their own image.

Coventry forms a chapter in Gavin Stamp’s Britain’s Lost Cities, a remarkable – if depressing – coffee table book illustrating what was done to our urban centres. Stamp wrote:

British propaganda was quick to exploit this catastrophe to emphasise German ruthlessness and barbarism and to make Coventry into a symbol of British resilience. Photographs of the ruins of the ancient Cathedral were published around the world, and it was insisted that it would rise again, just as the city itself would be replanned and rebuilt, better than before.

But the story of the destruction of Coventry is not so simple or straightforward. … severe as the damage was, a large number of ancient buildings survived the war – only to be destroyed in the cause of replanning the city. But what is most shocking is that the finest streets of old Coventry, filled with picturesque half-timbered houses, had been swept away before the outbreak of war – destroyed not by the Luftwaffe but by the City Engineer. Even without the second world war, old Coventry would probably have been planned out of existence anyway.

In one respect, Coventry had been ready for the attacks … the vision of “Coventry of Tomorrow” was exhibited in May 1940 – before the bombing started. [City engineer] Gibson later recalled that “we used to watch from the roof to see which buildings were blazing and then dash downstairs to check how much easier it would be to put our plans into action”.

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings had estimated that 120 timber houses had survived the war … two thirds of these would disappear over the next few years as the city engineer pressed forward with his plans … A few buildings were retained, but removed from their original sites and moved to Spon Street as a sanitised and inauthentic historic quarter.

Today, whatever integrity the post-war building ever had has been undermined by subsequent undistinguished alterations and replacements. Coventry has been more transformed in the 20th century than any other city in Britain, both in terms of its buildings and street pattern. The three medieval spires may still stand, but otherwise the appearance of England’s Nuremberg can only be appreciated in old photographs.

In fact, the destruction had begun before the war. In order to make the city easier for drivers, the west side had been knocked down in the 1930s, the area around Chapel St and Fleet St replaced by Corporation St in 1929-1931. After the war it would become a shopping centre.

Old buildings by Holy Trinity Church were destroyed in 1936-7, and that same year Butcher Row and the Bull Ring were similarly pulled down, the Lord Mayor calling the former “a blot in the city”.

Indeed, the city architect Donald Gibson hailed the Blitz as “a blessing in disguise. The Jerries cleared out the core of the city, a chaotic mess, and now we can start anew.” He said later that “We used to watch from the roof to see which buildings were blazing and then dash downstairs to check how much easier it would be to put our plans into action”.

Gibson’s plan became city council policy in February 1941, with a new civic centre and a shopping precinct inside a ring road. The City Engineer Ernest Ford wanted to preserve some old buildings, including the timber Ford’s Hospital, which had survived the Blitz. Gibson said it was an “unnecessary problem” and in the way of a new straight road.

September 24, 2023

Operation Market Garden Begins – WW2 – Week 265 – September 23, 1944

World War Two

Published 23 Sep 2023Monty’s Operation(s) Market Garden, to drop men deep in the German rear in the Netherlands and secure a series of bridges, begins this week, but has serious trouble. In Italy the Allies take Rimini and San Marino, but over in the south seas in Peleliu the Americans have serious problems with Japanese resistance. Finland and the USSR sign an armistice, and in Estonia the Soviets take Tallinn, and there are Soviet plans being made to enter Yugoslavia.

(more…)

September 22, 2023

Is the Slovak Uprising Doomed to Fail? – War Against Humanity 115

World War Two

Published 21 Sep 2023Even as they battle an uprising in Slovakia, the Nazis see the opportunity to continue their racial realignment of Europe. The latest victims of this genocidal legacy are Anne Frank and her family, who arrive at Auschwitz. In Britain, the V-1 menace is defeated. But as London breathes a sigh of relief, the Nazis and their allies reduce Warsaw to rubble in a rampage of burning, looting, rape, and murder.

(more…)

September 21, 2023

Iranian Railways, Red Cross Care Packages, and Tail Gunners – WW2 – OOTF 31

World War Two

Published 20 Sept 2023How did the Allies build and manage an enormous railway supplying the Soviet Union through Iran? How did the Red Cross deliver aid parcels through enemy territory to Allied POWs? And, how effective were the rear gunners in ground attack aircraft like the Stuka and Sturmovik? Find out in this episode of Out of the Foxholes.

(more…)

September 19, 2023

Jeremy Clarkson’s The Greatest Raid of All

North One

Published 4 May 2020Due to copyright restrictions, some music and scenes have been altered or removed in this upload. You can find the original unaltered documentary here: The Story Of The …

Jeremy Clarkson tells the story of the audacious commando raid on the German occupied dry dock at St Nazaire in France on March 28th 1942. Made for the BBC in 2007 by North One.

(more…)

September 18, 2023

Learning lessons from the plight of the British army in 1940

Lessons from history are only occasionally learned easily … they’re more likely brought to our attention by the Gods of the Copybook Headings after we’ve suffered some awful setback. As the latin tag would have it, Si vis pacem, para bellum: if you want peace, be prepared for war. Most western democracies refuse to believe this is true, and one of the easiest things for peacetime democratic governments to do is to short-fund the military and use the “savings” for more politically popular things that will help them get re-elected. The Canadian government has been a shining example of this since the late 1960s, with no end in sight.

A recent book on the British army, tracing its decline from the end of the First World War to the defeat in the Battle of France in 1940 shows just how quickly a world-beating army can be reduced to second-best in its next conflict. Richard Dannatt & Robert Lyman, the authors of Victory: the British Army 1918-1940 to Defeat, had an article in the Sunday Mail, illustrating the parallels between the army in their book and the British army today:

WHEN IT comes to national defence, never take your eye off the ball. That is a lesson we can and must learn from history. Because the disturbing fact is that this country did just that in the 1920s and 1930s in the aftermath of the First World War and the result very nearly cost us our freedom as Hitler’s forces threatened our shores.

Britain won the war in 1918 but then shamefully lost the peace as our army was allowed to atrophy.

It is often forgotten how professional the British Army had become by 1918, to pull off a stunning battlefield victory over the Germans in northern France in the final Hundred Days of the war.

It had been a long time coming after years of static trench warfare and no decisive breakthrough, just massive loss of life in the blood baths at Ypres, Verdun, the Somme and Passchendaele.

But finally, at the Battle of Amiens, British commanders — often wrongly caricatured as dunderheads and “donkeys” leading lions – demonstrated that they were able to understand and master the intricacies of the modern battlefield. With their sophisticated co-ordination of all elements of combat power — infantry, artillery, air power, armour — the stalemate was broken.

Modern war-fighting skills, technology and methods — learned at great cost in lives over the previous three-and-a-half years — secured victory for the British Army and its allies in 1918 as the Germans admitted defeat and sued for peace.

And yet little more than 20 years later, the boot was on the other foot as the next generation of German soldiers poured into France and defeated the Allies in a lightning campaign that ended with British troops fleeing from the beaches of Dunkirk.

How had victory in 1918 turned so quickly to defeat and humiliation in 1940?

The answer is that it had become the deliberate policy of successive British governments to downgrade the Army — a lesson we must learn today, with a new Defence Secretary who knows little about the brief.

Spending on defence was dramatically slashed amid an ill-thought-through assumption that there would not be another major war within ten years and so.

So far as the then government was concerned, the “war to end all wars” (as the Great War was dubbed) had done its job. There was no need to consider or plan for a future one, whether in policy, financial or practical terms. Everything was an issue of money as budgets were decided by Treasury civil servants with no military advice.

The principal reason why the Army was so unprepared for war in 1939 was that the British government, through faulty defence planning and financing in the previous two decades, made it so.

September 17, 2023

The Ballad of Chiang and Vinegar Joe – WW2 – Week 264 – September 16, 1944

World War Two

Published 16 Sep 2023The Japanese attacks in Guangxi worry Joe Stilwell enough that he gets FDR to issue an ultimatum to Chiang Kai-Shek, in France the Allied invasion forces that hit the north and south coasts finally link up, the Warsaw Uprising continues, and the US Marines land on Peleliu and Angaur.

(more…)

Why Operation Market Garden Failed and Its Devastating Consequences

OTD Military History

Published 5 Apr 2023Why did Operation Market Garden fail and what were the consequences of this failure? This video covers the operation, the reasons for the failure, and its devastating aftermath. The impact Market Garden had on the Dutch during the Hunger Winter and Allied soldiers during the Battle of the Scheldt is explored.

There is footage of the 101st US Airborne, 82nd US Airborne, British 1st Airborne Division, and the troops of the British XXX Corps featured in the video.

(more…)

September 16, 2023

France’s Vietnam War: Fighting Ho Chi Minh before the US

Real Time History

Published 15 Sept 2023After the Second World War multiple French colonies were pushing towards independence, among them Indochina. The Viet Minh movement under Ho Chi Minh was clashing with French aspirations to save their crumbling Empire.

(more…)

September 15, 2023

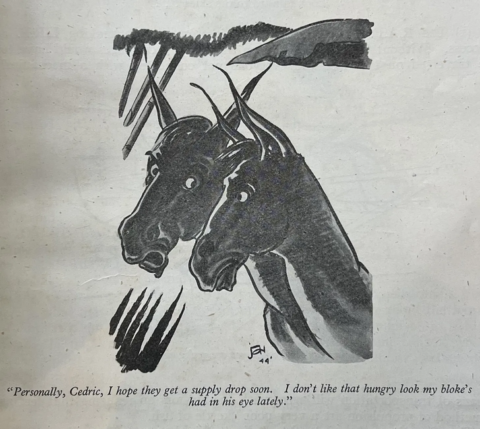

Learning to handle mules to accompany Chindit columns in WW2

Robert Lyman posted some interesting details from veteran Philip Brownless of how British troops in India had to learn how to handle mules and abandon their motor transport in order to get Chindit columns into Japanese territory in Burma:

Soon after our return from the Arakan front in the autumn of 1943, we were in central India, and had been told that the whole division was to be handed over to General Wingate and trained to operate behind the Japanese lines. All our motor transport was to be taken away and we were to be entirely dependent upon mules for our transport.

The C.O. one evening looked round the mess and then said to me “You look more like a country bumpkin than anybody else. You will go on a veterinary course on Tuesday and when you come back you will take charge of 44 Column’s mules.”

I had never met one of these creatures before. On arriving at Ambala I reported to the Area Brigade Major who wasn’t expecting me and seemed to have no clue about anything. He said “You’d better go down to the Club and book in”. I reported to the Club, a comfortable looking establishment, and they seemed to have a vague idea that a few bodies like me might turn up on a course and were apologetic that I would have to sleep in a tent but otherwise could enjoy the full facilities of the Club. I was shown the tent, an EPIP tent or minor marquee, with a coloured red lining and golden fleur de lys all over it, (very Victorian) with a small office extension with table and chair in front and another extension at the back with bath, towel rail and a fully bricked floor. Having lived either in a tent or under the stars in both the desert and the Arakan for the last 2 years, this struck me as luxury indeed. Even better, I took on a magnificent bearer, with suitable references, whom I found later was some kind of Hindu priest. I soon got used to having my trouser legs held up for me to put my feet in, and being helped into the rest of my clothes. I had a comfortable 3 weeks learning all about mules.

I discovered all sorts of things like the veterinary term “balls”, which were massive pills which were given to the mule by – first of all grabbing his tongue and pulling it out sideways so he couldn’t shut his mouth on your arm, and then gently throwing the ball at his epiglottis and making sure it went down. Then you let go of his tongue and gave him a nice pat. One of our lecturers, an Indian warrant officer, knew his stuff well and was so pleased about it that when he asked a question he would give you the answer himself. He liked being dramatic and loved to finish a description of some fatal ailment by saying “Treatment, bullet”.

Many of the men in our battalion were East Enders; others came from all over Essex. A few were countrymen, two were Irish and knew all about horses, one sergeant had been in animal transport and one invaluable soldier had been an East End horse dealer. The large majority had had nothing to do with animals: however, the saving grace was that English soldiers seem to be naturally good with animals and soon learned to handle them well. I arranged to get some instruction from the nearby unit of Madras Sappers and Miners and we borrowed a handful of trained mules from them for the men to practise handling, tying on loads and learning to talk to them.

Then came the great day when we were to draw up our main complement of animals, about 70 mules and 12 ponies. We were dumped at a small railway station. It was all open ground and there was a team of Army Veterinary Surgeons to allocate fairly between the three battalions, the Essex, the Borders and the Duke of Wellington’s. Lieut. Jimmy Watt of the Borders was a pal of mine: he and I, with a squad of men were to march them back nearly 100 miles to our camp, sleeping each of the five nights under the stars. As soon as we arrived at the disembarkation site I got all our mule lines laid out, with shackles (used to tie mules fore and aft) and nosebags ready. I had also picked up the tip that the mules would be wild, having spent three days in the train, and almost impossible to hold, so I instructed our men to tie them together in threes before they got off the train. As all three pulled in different directions, one muleteer could hold them. Not everybody had learned this trick so the result was that wild mules were careering all over the place, impossible to catch. When our first handful of mules arrived, they were quickly secured in a straight line and fed. They were familiar with lines like this and cooled down at once, long ears relaxed and tails swishing amiably. When the wild mules careering round saw this line, they said to themselves “We’ve done this before” and came and stood in our lines. We shackled them and I picked out the moth-eaten ones and sent them back to the vets who kept sending polite messages of thanks to Mr. Brownless for catching them. We finished up with a very good set of mules. Jimmy Watt and I had a bit of a conscience about the Duke of Wellington’s so we picked them out a really good pony. We felt even worse a few weeks later when it was sent back to Remounts with a weak heart! The Brigade Transport Officer visited us the second evening so Jimmy Watt and I walked him round rather quickly, chatting hard, to approve the allocation of animals, and he agreed with our arrangement.

In a highly optimistic mood early on, I decided to practise a river crossing. We marched several miles out from camp to a typical wide sandy Indian river, 300 yards across, made our preparations, i.e. assembling the two assault boats, making floating bundles of our clothes and gear by wrapping them in groundsheets, unsaddling the animals, and assembling at the water’s edge. A good sized detachment of muleteers was posted on the opposite bank ready to catch the mules. The mules waded into the shallow water but no one could get them to move off. We tried all sorts of inducements in vain and then suddenly, one sturdy little grey animal decided to swim and the whole lot immediately followed. Calamity ensued! Mules are very short sighted and could only dimly see the opposite bank but downstream was a bright yellow sandy outcrop and they all made for this. The muleteers on the other bank, when they realised what was happening, ran through the scrub and jungle as fast as they could, but the mules arrived first and bolted off into the wilds of India. I swam my pony across with my arm across his withers and directing him by holding his head harness, the gear was ferried across and the mule platoon, with one pony, began the march back to camp. Deeply depressed, I wondered how to tell the C.O. I had lost all his mules and imagined the court martial which awaited me (or, serving under General Wingate, would I be shot out of hand?) An hour and a half later we came in sight of the camp and to my utter astonishment I could see the mules in their lines. When I arrived at the mule lines, the storeman met me and said that the whole lot had arrived at the double and had gone to their places. He had merely gone along the lines, shackling them and patted their noses. Salvation! I kept quiet for a bit but it got out and I was the butt of much merrymaking.