Behold the peacock in all its glory: As an evolved organism, it doesn’t make sense. The peacock can barely fly, and its extravagant tail feathers signal “Hey, here’s lunch!” to predators for miles around. So why the fancy look? Simple: The girls love it. Peacocks with the biggest and most dazzling tail feathers mated with lots of adoring peahens and begat lots of offspring, a process that resulted in the utterly useless but amazing-looking birds that we decorate our parks with today.

The “peacock principle” provides the answer to one of the abiding mysteries of nature: Males will evolve into any sort of weirdness to attract females. Since psychology recapitulates phylogeny, I have personally experienced the peacock principle. In my callow youth, I grew my hair to enormous length and strutted around in ridiculously colored garments. My bewildered parents thought I had become gay, but the explanation was the exact opposite of that. Long hair and gaudy clothes were my peacock feathers.

Martin Gurri, “Get the Kids Out of the Room — We’re Going To Talk About Sex”, Discourse, 2022-04-25.

August 5, 2022

QotD: The Peacock’s feathers

August 1, 2022

The fertilizer front in Justin Trudeau’s renewed war on Canada’s farmers

In The Line‘s weekly dispatch, one of the items discussed was the Trudeau government’s decision to follow the Netherlands and Sri Lanka down the path of ensuring that millions may be at risk of starvation to mollify the global warming lobby and the WEF:

In 2020, the federal government announced a plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions arising from fertilizer application by 30 per cent below 2020 levels within the next decade. The targets, then fairly vaguely spelled out, have been a subject of considerable consternation among farmers in the wheat belt ever since. However, as the feds moved into a consultation process, set to end by the end of August, it’s now become clear that those targets are a little more set in stone than they had previously feared. Further, the “consultation” process is looking increasingly tokenistic.

“The commitment to future consultations are only to determine how to meet the target that Prime Minister Trudeau and Minister Bibeau have already unilaterally imposed on this industry, not to consult on what is achievable or attainable,” according to a press release sent out jointly by the Alberta and Saskatchewan agriculture ministers last week.

Why does this matter? Well, firstly because these emissions targets are coming on top of tariffs placed on chemical precursors to fertilizer coming out of Russia. And further because according to industry lobbyists and many farmers themselves, it’s not going to be possible to meet these kinds of emissions targets without significantly reducing fertilizer use — which is already efficiently applied owing to the fact that the stuff is expensive.

The meat of it (ha!) is that if we reduce fertilizer use further, there is significant fear that we will cut into food yields, just as the world’s growing population is facing a possible famine thanks to war. It’s not like these concerns are temporary, either. In the long run, climate change is only going to add to food insecurity; and Canada may be well-positioned in a changing climate to address the global food supply.

And, yeah, all of this is very ironic. Of course we should be doing all we can to cut emissions, but, perhaps — just hear us out, here — given the broader geopolitical realities, agriculture is not the most obvious or well-placed target for those emissions cuts. Especially considering Canada still accounts for a very small fraction of global greenhouse emissions overall. (Yes, we know our per-capita emissions are high. That’s the unfortunate consequence of living in a very cold, poorly populated expanse. However, our actual population remains low. These two facts are not coincidences!)

Now, if we were going to give the federal government some benefit of the doubt, we’d point out that we’re still in a consultation process. We’d also further point out that if the government wanted to reduce agriculture emissions, there are probably some smarter ways to go about it — equipment upgrades, for example. Investments in soil testing could go a long way to helping farmers apply nitrogen more efficiently, which could help them increase yields while maintaining profits. Win-win!

Yet, from what we’ve seen from this government since the last election, we’re not betting on sensible, win-win solutions. Farmers in the Netherlands have been so put out by similar climate-change inspired emissions cuts that they’ve engaged in convoy-like protests themselves. Further, we suspect the Trudeau government salivates at the prospect of a bunch of another round of spitting-mad, truck-driving farmers rolling into Parliament to protest climate change policies. Every pissy article in the Federalist is a win to this cabinet.

If you’re angering the right people, you’re winning, right?

And how do we imagine arcane policies like this are going to play out internationally in the next three to nine months, if we witness more and more developing countries closing borders to grain exports and significant swathes of the developing world look set to starve? How well are these climate-change policies going to sit against real, hard geopolitical realities like a frozen Europe in winter or significantly curtailed industrial production in Germany, leading to further supply chain issues and economic recession?

If this government is not careful, they’re going to drag a lot of the progressive movement — and its genuinely very noble ideals — along with it. This is a government that appears to have said “fuck it,” retreating ever deeper into self-reinforcing ideological bubbles as the world decides it has much bigger problems than those that the Trudeau government seems able to address. To put it bluntly, how are pious climate-change goals going to look if they have to be measured against piles of emaciated bodies in the developing world? Because that’s the danger. Nobody in Canada is going to starve.

July 28, 2022

“… this time it will be worldwide”

Elizabeth Nickson recounts her journey from dedicated environmentalist to persecuted climate dissident and explains why so many of us feel as if we’re living on the slopes of a virtual Vesuvius in 79AD:

A screenshot from a YouTube video showing the protest in front of Parliament in Ottawa on 30 January, 2022.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

I was experiencing a time-worn campaign to shut down a voice that conflicted with an over-arching agenda. And in the scheme of things, I was nothing. But in fact, I was almost the only one, everyone else had been chased out. I was an easy kill, required few resources. It was personal, it was vicious beyond belief, and it had nothing to do with truth. If I had continued my work in newspapers, they would have attacked my mother and my brothers, two of the three of whom were fragile.

As of now, this has happened to hundreds of thousands of people in every sector of the economy. The chronicles of the cancelled are many and varied, and they all start with the furies, unbalanced, easily triggered and marshalled to hunt down and kill an enemy. These programs, pogroms, are meticulously planned, they analyze you, find your weakness, and attack it. In my case, it was my solitude, my income, my need to look after my family that made me an easy sacrifice.

I was such an innocent. I thought with my hard-won skills, my ability to reason, to number crunch, to apply economic theory and legit charting, and report, the truth would be valuable, useful.

Every single member of the cancelled has had their faith in the culture badly shaken. They all thought, as I did, that we were in this together, we needed the truth in order to make good decisions, decisions that would promote the good of all.

Not now. Not anymore.

The truth I found behind the fields and forests of the natural world is animating people on the streets in Europe today, the Dutch, French and German farmers. It animated the revolution in Sri Lanka.

Because what I and hundreds of others had found was censored, the destructive agenda has advanced to the point where their backs are against the wall. They don’t have a choice. They have to win. And they are in the millions.

Same with Trump’s people. They aren’t mindless fans or acolytes or sub-human fools. Their backs are against the wall. They have no choice but to fight.

But because I and the many like me, who know what happened, were shut down, disallowed from writing about it, cancelled and vilified, no one understands why this is happening in any depth. City people mock and hate rural people. My photographer colleague/best friend in New York: “racists as far as the eye can see”. My old aristocratic bf London: “Pencil neck turkey farmers”. No city person can take on board that they have allowed legislation and regulation which is destroying the rural economy because they have been brainwashed by the hysteria in the environmental movement. This destruction is not the only reason but it is the fundamental reason for our massive debts and deficits. The base of the economy has been destroyed. We have lost two decades of real growth.

And we did it via censorship.

There is a truism about revolutions in China. All of a sudden, across this great and massive country with its five thousand year culture, people put down their tools and start marching towards the capital, hundreds of millions all at once.

We are almost there. But this time it will be worldwide.

July 23, 2022

Some of the events that lead to the Dutch farmers’ revolt

In UnHerd, Senay Boztas provides a useful chronology of how the Netherlands government managed to piss off so many Dutch farmers, leading to the protests we are still seeing (even if the legacy media is doing their best to ignore it):

“For many farmers it’s the end of their business and they will fight until the last. Sometimes these farms go back generations, they were built by hand, and people feel farmers heart and soul. This is all being taken away.”

Jan Brok, vice chairman of the BoerBurgerBeweging (BBB) party, understands why Netherlands farmers have spent the past month blockading food distribution centres, roads and ministers’ driveways. They are horrified by a new environmental policy that will mean a likely 30% reduction in livestock.

The Netherlands is a country of four million cattle, 13 million pigs, 104 million chickens, and just over 17 million people. It is Europe’s biggest meat exporter with a total area of just over 41,000 square kilometres, and a fifth of this is water. It is one of the world’s most densely populated countries, with the EU’s highest density of livestock.

But there is a significant cost to this abundance: the local environmental impact. Such intensive agriculture, and livestock farming in particular, creates harmful pollution. Manure and urine mix to produce ammonia, and together with run-off from nitrogen-rich fertiliser on fields ends up in lakes and streams, where it can promote excessive algae that smothers other life. Manure here is not a vital fertiliser but a problem waste product.

For decades, this success in trade and agriculture has been accompanied by high emissions of harmful nitrogen compounds, including nitrogen oxides emitted by industry and transport. Levels were dropping, and in 2015, the Dutch introduced a “trading scheme” known as the Programmatische Aanpak Stikstof (PAS) to try to reduce the pollution.

But a Council of State court ruling in 2019 — on a case brought by two local environmental organisations against various farms — ruled that this offsetting scheme was invalid. Permission could not be granted for polluting projects or farm expansion in exchange for promised nitrogen-related reductions in the future: the reductions needed to come first.

The government panicked: national shutdowns were put in place, building projects were put on hold and traffic speeds reduced to 100 kph in the daytime on major roads; it was also obvious that farming was a problem — something needed to be done about all ammonia, nitrogen oxide and nitrous oxide emissions.

Then, in January, the conservative-liberal-Christian coalition pledged to halve nitrogen production by 2030, with a €25 billion budget to back it up. That money was the loud part. The quiet part included the possibility of expropriation, of the government forcibly purchasing farmland. Plans drawn up by civil servants include slashing livestock numbers by 30%. More than €500 million is being brought forward for regional government to buy out farmers this year and next.

Leading the charge among the coalition partners are the Democrats 66 (D66) party. They insisted on “real action for the climate” in their last manifesto. Tjeerd de Groot, the D66 nature and farming spokesman, pointed out that the Netherlands is Europe’s biggest nitrogen emitter, followed by Belgium and Germany. He told a current affairs programme last week: “It is absolutely essential — but also painful — that the plans go through.”

In June, the government published two documents. One: a map showing the areas that need to reduce emissions by between 12% and 95%. The second was a statement that aimed to help farmers — which De Groot admits failed spectacularly. Farmers saw ruin, not a pair of documents. They looked at the percentage reduction figures next to their farms, and began interpreting how many cattle they would need to cull. It was an enormous blow. Many of them had made huge, expensive investments in new equipment to reduce the environmental impact of their herds.

Hence the massive uprising.

July 21, 2022

Farmers’ protests against insane environment mandates continue in the Netherlands

For some unknown reason, the huge protests by Dutch farmers against ridiculous environment-protection rules seems to be getting almost no media coverage. As Rex Murphy pointed out in the National Post, if this was happening in Canada, the government would already have imposed the Emergencies Act and be actively depriving people of their civil rights across the board. Somehow, this protest is uninteresting to most of the legacy media, but as Brendan O’Neill explains, it is a huge deal:

This strange, sunny week has provided the best proof yet that the West’s elites have taken leave of their senses. That they have fully retreated from reason, and from reality itself. As farmers and workers across the world continue to rise up against the tyrannical consequences of climate-change alarmism, what are the elites doing? Engaging in yet more climate-change alarmism. Wringing their hands over the hot weather and its forewarning, as they see it, of the manmade heat-death of the planet that is apparently just around the corner. They continue to peddle the very politics of eco-dread that is whacking farmers and the working class and storing up problems for us all.

The contrast could not have been more stark. On one side we have farmers everywhere from Ireland to the Netherlands to, of course, Sri Lanka making it as plain as they can that the warped ideology of Net Zero will make it harder for them to produce the food that humanity needs. And on the other side we have the Net Zero fanatics of the upper middle classes continuing to push their dire, destructive green ideology. The heatwave proves we must cut emissions even faster and more severely, they tweet in their breaks from sunning themselves in their spacious gardens, even as farmers tell them that the zealous obsession with cutting emissions will make it harder to grow crops. So this is where we’re at – with a ruling class more invested in fact-lite narratives of apocalypse than in the basic responsibility of a society to make food.

This politics is best understood as luxury apocalypticism. It is clearer than it has been for a very long time that the fantasy of the end of the world, of marauding, industrious mankind polluting itself into oblivion, is something only the well-off and time-rich can afford to indulge. The dream of eco-doom is a simultaneously self-hating and self-serving political narrative. It expresses the elite’s turn against the very modernity they helped to create while also flattering their belief that only they can save us. That only their plans to slash emissions, to cut back on global travel and generally to shrink the “human footprint” can hold Armageddon at bay. The great benefit of the global revolt of farmers and workers is that it is injecting a truth and a realism into public discussion that might just help to push back the luxurious and ruinous ideologies of the new elites.

Everywhere, farmers are saying “Enough”. In the Netherlands farmers have been revolting for weeks against their government’s perverse demands that they slash their use of nitrogen compounds. The Dutch government, under pressure from the EU, has committed itself to cutting its nitrogen emissions in half by 2030. This would entail farmers getting rid of vast numbers of their livestock, crushing their ability to make a living and to produce what needs to be produced. So we have the truly surreal situation where Dutch farmers are protesting in their thousands for the right to feed the people of the Netherlands while the elites of the Netherlands demonise them, harass them and even shoot at them. I can think of no better illustration of the loss of logic and humanity within the modern elites than this strange spectacle.

July 20, 2022

Climate change is nothing new, and it was warmer in England for a few hundred years in the Middle Ages

If you’ve been reading the blog for a while, you’ll have noticed that I’m not a fan of trying to panic people about climate change … catastrophism just isn’t my thing. I certainly don’t deny that climate change happens and I agree that it is happening now, but I’m highly skeptical that human action has more than a minor influence compared to the ups and downs of long-term climate shifts driven by natural forces. Ed West has a thumbnail sketch of just how much the European (and especially English) climate change impacted ordinary people during the Middle Ages:

Chart from the Journal of Quaternary Science Reviews showing Greenland ice core data over the last 10,000 years. At the end of the Minoan Warming came the Bronze Age Collapse, after the Roman Warming came the fall of the western Roman Empire.

The climate is changing, with all that entails, something we’ve known about for several decades now. Among the early proponents of the theory of climate change was mid-century climatologist Hubert Lamb, who spent most of his career at the Met Office and during the course of his studies made a curious historical discovery.

It was once widely believed that climate remained relatively stable over recorded history, civilisational lifespans being too brief to see such grand changes. But while looking into medieval chroniclers, Lamb was struck by the numerous references to vineyards in England, some as far as the midlands. As long as anyone had ever remembered, the country had been too cold to grow wine, except in tiny pockets of Sussex which occasionally produced almost-drinkable white.

William of Malmesbury, living in the 12th century, observed of his native Wiltshire that “in this region the vines are thicker, the grapes more plentiful and their flavour more delightful than in any other part of England. Those who drink this wine do not have to contort their lips because of the sharp and unpleasant taste, indeed it is little inferior to French wine in sweetness.” How could that have been?

Lamb concluded that Europe must have been considerably warmer during the Middle Ages, and in 1965 produced his great study outlining the theory of the Medieval Warm Period; this posited that Europe was at its hottest in the High Middle Ages (1000-1300) and then became unusually cool between 1500 and 1700.

Since then, Lamb’s thesis has been reinforced by analysis of pollen in peat bogs, as well as the radioactive isotope Carbon-14 found in tree rings (the less sun, the more Carbon-14). In Medieval Europe, every summer was a hot girl summer — and tiny changes could make earth-shattering differences.

The people of Europe enjoyed that extended period of warmer weather for about 300 years, then things suddenly got far worse:

Across Europe, people must have noticed a change. Farmers in the Saastal Valley in Switzerland were probably the first to observe what was happening, back in the 1250s, when the Allalin Glacier began to flow down the mountain. Surviving plant material from Iceland suggests an abrupt decrease in the temperature from 1275 — and, as Rosen points out, a reduction of one degree made a harvest failure seven times more likely. From 1308 England saw four cold winters in succession; the Thames froze, chroniclers recalling dogs chasing rabbits across the icy surface for the first time.

As with many things, change was gradual, until it was dramatic, for then came the disastrous year of 1315. The Chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis, written by a monk at the Abbey of Saint-Denis outside Paris, recorded that in April the rains came down hard — and didn’t stop until August.

Drenched and starved of sunlight, the crops failed across Europe. The price of food doubled and then quadrupled. By May 1316, crop production in England was down by up to 85 percent and there was “most savage, atrocious death”, as a chronicler put it. Hopeless townsfolk walked into the countryside, searching for any bits of food; men wandered across the country to work, only to return and find their wives and children dead from starvation. At one point, on the road near St Albans, no food could be found even for the king. Emaciated bodies could be seen floating face down in flooded fields.

The Great Famine killed anywhere between 5-12% of the European population, although some areas, such as Flanders, suffered far worse death rates, losing up to a quarter of their population to hunger.

July 12, 2022

“Misrepresentation, exaggeration, cherry picking or outright lying … in support of the theory of imminent catastrophic global warming”

Y’know, the folks at The Daily Sceptic really need to tell us what they think instead of cloaking their opinions in euphemisms:

Two top-level American atmospheric scientists have dismissed the peer review system of current climate science literature as “a joke”. According to Emeritus Professors William Happer and Richard Lindzen, “it is pal review, not peer review”. The two men have had long distinguished careers in physics and atmospheric science. “Climate science is awash with manipulated data, which provides no reliable scientific evidence,” they state.

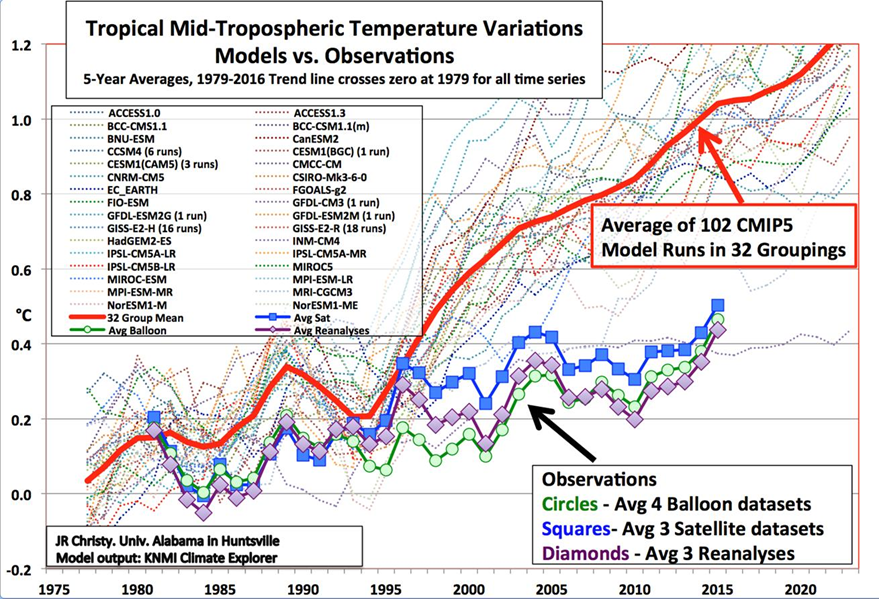

No reliable scientific evidence can be provided either by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), they say, which is “government-controlled and only issues government dictated findings”. The two academics draw attention to an IPCC rule that states all summaries for policymakers are approved by governments. In their opinion, these summaries are “merely government opinions”. They refer to the recent comments on climate models by the atmospheric science professor John Christy from the University of Alabama, who says that, in his view, recent climate model predictions “fail miserably to predict reality”, making them “inappropriate” to use in predicting future climate changes.

The “miserable failure” is graphically displayed below. Since the observations cut-off, global temperatures have again paused.

Particular scorn is poured on global surface temperature datasets. Happer and Lindzen draw attention to a 2017 paper by Dr. James Wallace and others that elaborated on how over the last several decades, “NASA and NOAA have been fabricating temperature data to argue that rising CO2 levels have led to the hottest year on record”. The false and manipulated data are said to be an “egregious violation of scientific method”. The Wallace authors also looked at the Met Office HadCRUT database and found all three surface datasets made large historical adjustments and removed cyclical temperature patterns. This was “totally inconsistent” with other temperature data, including satellites and meteorological balloons, they said. Readers will recall that the Daily Sceptic has reported extensively on these issues of late and has attracted a number of somewhat footling “fact checks”.

Happer and Lindzen summarise: “Misrepresentation, exaggeration, cherry picking or outright lying pretty much covers all the so-called evidence marshalled in support of the theory of imminent catastrophic global warming caused by fossil fuels and CO2.”

July 6, 2022

The ongoing protests by Dutch farmers demand your attention

Protests in many countries in the western world can get violent and even be claimed (by the targets of the protest) to be “insurrections”, but protests in the Netherlands always have more of an edge to them than elsewhere, because when the Dutch really get angry they have, in the past, gone so far as to kill AND EAT their prime minister. The current protests haven’t gone that far yet, but politicians should keep in mind that Dutch farmers can react primally to being treated in the way the Soviets treated the kulaks:

This is really important – you know, on the level of “pay attention or your food supply is next”.

We reported last week that Dutch farmers were attacking government vehicles, blocking roads, and dumping manure on government buildings in response to a new “climate” policy that shut down numerous family farms because their cows were farting too much.

These farmers are now banned from working their own land to feed their families.

Let me explain what’s happening and why it is of the utmost importance as I randomly drop in videos of what the Dutch farmers are doing to keep your attention.

Unelected elites at the World Economic Forum, World Bank, United Nations, and BlackRock think us little people are rodents that are polluting the Earth, and that it’s their job to cull us and tame us so we can follow their smartypants amazingness into what is obviously a glorious future.

These elites get corporations to fall in line by promoting “Environmental-Social-Governance” metrics (a scorecard, if you will) that shows how many woke policies a company is adopting. Do they have a climate pledge? Are they hiring based on skin color, gender, and sexual fetish? Do they fly a rainbow flag over their headquarters? Do they have at least a few dozen “equity” executives to make sure everyone is a good little Marxist?

Companies lose customers by joining this radical, perverse cult, but they get access to the trillions of dollars represented by the elites and the corrupt organizations, from the WEF to the WHO to the mega-investment firms. They don’t care if you boycott them because they are expecting to simply outlast you.

The elites then get governments to fall in line by lobbying, pushing big money into local elections, and taking over school boards and classrooms to ensure good little disciples are being churned out to vote for the right people. They get young people riled up, telling them the planet is burning and that unarmed black men are yelling “Hands up, don’t shoot!” while being gunned down by racist white cops in the streets. Good people watch as their cities burn and politicians bail out the rioters.

July 4, 2022

(Very expensive) roads, bridges, and railways to nowhere

In Palladium, Brian Balkus wonders why American can’t build anything any more:

Construction of the Fresno River Viaduct in January 2016. The bridge is the first permanent structure being constructed as part of California High-Speed Rail. The BNSF Railway bridge is visible in the background.

Photo by the California High-Speed Rail Authority via Wikimedia Commons.

Sepulveda’s cost and schedule overrun aren’t even the worst of it. Just as unattainable as a shortened commute is the Californian dream of building a bullet train that could take you from Los Angeles to San Francisco in under three hours. In 2008, a year before the Sepulveda project began, the state tried to turn this dream into a reality after voters approved a 512-mile high-speed rail (HSR) project. Amid failing overseas wars and financial crises, at the time it could’ve become a symbol of renewal not just for California but the entire country. Instead, it came to exemplify a dysfunctional government that lacks the capacity to build.

At the time California began accelerating the development of its HSR system it only had 10 employees dedicated to overseeing what was the most expensive infrastructure project in U.S. history. It ended up 14 years (and counting) behind schedule and $44 billion over budget. Incredibly, the state has not laid a single mile of track and it still lacks 10 percent of the land parcels it needs to do so. Half of the project still hasn’t achieved the environmental clearance needed to begin construction. The dream of a Japanese-style bullet train crisscrossing the state is now all but dead due to political opposition, litigation, and a lack of funding.

Despite its failure, the HSR project inaugurated the U.S.’s megaproject era. Once a rare type of project, by 2018 megaprojects comprised 33 percent of the value of all U.S. construction project starts. An alarming number of these have spiraled out of control for many of the same reasons that killed the California bullet train. The decade that followed the financial crisis was a kind of inflection point in the industry; this was when construction projects became noticeably worse and when the long-term implications could no longer be ignored. One of the most cited studies of the U.S.’s declining ability to build reviewed 180 transit megaprojects across the country, revealing that today, U.S. projects take longer to complete and cost nearly 50 percent more on average than those in Europe and Canada.

Having joined Kiewit in 2010, I witnessed these changes first-hand. I have since moved on, but have remained in the broader industry, including working on what are called “strategic pursuits” — the process by which companies compete for megaprojects. This experience has provided insight into the mechanics of how these projects are awarded and why they so frequently fail.

Even if the construction had proceded close to schedule, the economic justification for California’s high speed rail line was never strong … and it’s unlikely the service would have come close to breaking even. It almost certainly would have added significant ongoing costs to Californian taxpayers, and due to the nature of high speed rail services, been effectively a subsidy from working-class Californians to the laptop elites of Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay area.

All of that, however, are merely additional reasons to believe the project was doomed from inception. Broadly speaking, all major infrastructure projects in the United States are struggling with paperwork and compliance requirements mostly driven by state and federal environmental regulations passed with the best possible intentions (as the saying goes):

Sepulveda’s numerous lawsuits and stakeholder conflicts are an example of a phenomenon that can be traced back to the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969. NEPA mandates developers to provide environmental impact statements before they can obtain the permits necessary for construction on huge swathes of infrastructure.

Shortly following the passage of NEPA, California’s then-governor Ronald Reagan signed the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) into law, which required additional environmental impact analysis. Unlike NEPA, it requires adopting all feasible measures to mitigate these impacts. Interest groups wield CEQA and NEPA like weapons. One study found that 85 percent of CEQA lawsuits were filed by groups with no history of environmental advocacy. The NIMBY attitude of these groups has crippled the ability of California to build anything. As California Governor Gavin Newsom succinctly put it, “NIMBYism is destroying the state”.

It is also destroying the U.S.’s ability to build nationally. The economist Eli Dourado reported in The New York Times that “per-mile spending on the Interstate System of Highways tripled between the 1960’s and 1980’s.” This directly correlates with the passage of NEPA. If anything, the problem has gotten worse over time. Projects receiving funding through the $837 billion stimulus plan passed by Congress in the aftermath of the financial crises were subject to over 192,000 NEPA reviews.

The NEPA/CEQA process incentivizes the public agencies to seek what is often termed a “bulletproof” environmental compliance document to head off future legal challenges. This takes time, with the average EIS taking 4.5 years to complete. Some have taken longer than a decade. A cottage industry of consultants is devoted to completing these documents, earning themselves millions in fees.

June 28, 2022

If your gas can sucks – and it probably does – thank the EPA

The editors at FEE dug out an old classic article from Jeffrey A. Tucker that still holds up ten years later:

The gas gauge broke. There was no smartphone app to tell me how much was left, so I ran out. I had to call the local gas station to give me enough to get on my way. The gruff but lovable attendant arrived in his truck and started to pour gas in my car’s tank. And pour. And pour.

“Hmmm, I just hate how slow these gas cans are these days,” he grumbled. “There’s no vent on them.”

That sound of frustration in this guy’s voice was strangely familiar, the grumble that comes when something that used to work but doesn’t work anymore, for some odd reason we can’t identify.

I’m pretty alert to such problems these days. Soap doesn’t work. Toilets don’t flush. Clothes washers don’t clean. Light bulbs don’t illuminate. Refrigerators break too soon. Paint discolors. Lawnmowers have to be hacked. It’s all caused by idiotic government regulations that are wrecking our lives one consumer product at a time, all in ways we hardly notice.

It’s like the barbarian invasions that wrecked Rome, taking away the gains we’ve made in bettering our lives. It’s the bureaucrats’ way of reminding market producers and consumers who is in charge.

Surely, the gas can is protected. It’s just a can, for goodness sake. Yet he was right. This one doesn’t have a vent. Who would make a can without a vent unless it was done under duress? After all, everyone knows to vent anything that pours. Otherwise, it doesn’t pour right and is likely to spill.

It took one quick search. The whole trend began in (wait for it) California. Regulations began in 2000, with the idea of preventing spillage. The notion spread and was picked up by the EPA, which is always looking for new and innovative ways to spread as much human misery as possible.

An ominous regulatory announcement from the EPA came in 2007: “Starting with containers manufactured in 2009 … it is expected that the new cans will be built with a simple and inexpensive permeation barrier and new spouts that close automatically.”

The government never said “no vents”. It abolished them de facto with new standards that every state had to adopt by 2009. So for the last three years, you have not been able to buy gas cans that work properly. They are not permitted to have a separate vent. The top has to close automatically. There are other silly things now, too, but the biggest problem is that they do not do well what cans are supposed to do.

And don’t tell me about spillage. It is far more likely to spill when the gas is gurgling out in various uneven ways, when one spout has to both pour and suck in air. That’s when the lawn mower tank becomes suddenly full without warning, when you are shifting the can this way and that just to get the stuff out.

June 2, 2022

“Like many problems in American history, recycling began as a moral panic”

Jon Miltimore recounts the seminal event that kicked off the recycling pseudo-religion in North America:

The frenzy began in the spring of 1987 when a massive barge carrying more than 3,000 tons of garbage — the Mobro 4000 — was turned away from a North Carolina port because rumor had it the barge was carrying toxic waste. (It wasn’t.)

“Thus began one of the biggest garbage sagas in modern history,” Vice News reported in a feature published a quarter-century later, “a picaresque journey of a small boat overflowing with stuff no one wanted, a flotilla of waste, a trashier version of the Flying Dutchman, that ghost ship doomed to never make port.”

The Mobro was simply seeking a landfill to dump the garbage, but everywhere the barge went it was turned away. After North Carolina, the captain tried Louisiana. Nope. Then the Mobro tried Belize, then Mexico, then the Bahamas. No dice.

“The Mobro ended up spending six months at sea trying to find a place that would take its trash,” Kite & Key Media notes.

America became obsessed with the story. In 1987 there was no Netflix, smartphones, or Twitter, so apparently everyone just decided to watch this barge carrying tons of trash for entertainment. The Mobro became, in the words of Vice, “the most watched load of garbage in the memory of man.”

The Mobro also became perhaps the most consequential load of garbage in history.

“The Mobro had two big and related effects,” Kite & Key Media explains. “First, the media reporting around it convinced Americans that we were running out of landfill space to dispose of our trash. Second, it convinced them the solution was recycling.”

Neither claim, however, was true.

The idea that the US was running out of landfill space is a myth. The urban legend likely stems from the consolidation of landfills in the 1980s, which saw many waste depots retired because they were small and inefficient, not because of a national shortage. In fact, researchers estimate that if you take just the land the US uses for grazing in the Great Plains region, and use one-tenth of one percent of it, you’d have enough space for America’s garbage for the next thousand years. (This is not to say that regional problems do not exist, Slate points out.

The widespread imposition of recycling mandates across North America was probably an inevitable reaction to the voyage of the Mobro. For many people, this was the end of the story, as things that were previously just buried in landfill sites would now be safely and efficiently put back into the economy as re-used, re-purposed, or actual recycled products. Win-win, right?

Sadly, the economic case for recycling many items is weak to non-existant. The demand for recycled materials was lower than predicted and often only maintained through subsidies and hidden incentives that couldn’t last forever. Once the incentives went away, so did much of the created demand. Worse, the way a lot of the stream of recyclable materials was handled was by shipping it off to China or certain developing nations — in effect, paying them to take the problem off the hands of western governments. This resulted in even more problems:

Americans who’ve spent the last few decades recycling might think their hands are clean. Alas, they are not. As the Sierra Club noted in 2019, for decades Americans’ recycling bins have held “a dirty secret”.

“Half the plastic and much of the paper you put into it did not go to your local recycling center. Instead, it was stuffed onto giant container ships and sold to China,” journalist Edward Humes wrote. “There, the dirty bales of mixed paper and plastic were processed under the laxest of environmental controls. Much of it was simply dumped, washing down rivers to feed the crisis of ocean plastic pollution.”

It’s almost too hard to believe. We paid China to take our recycled trash. China used some and dumped the rest. All that washing, rinsing, and packaging of recyclables Americans were doing for decades — and much of it was simply being thrown into the water instead of into the ground.

The gig was up in 2017 when China announced they were done taking the world’s garbage through its oddly-named program, Operation National Sword. This made recycling much more expensive, which is why hundreds of cities began to scrap and scale back operations.

May 30, 2022

Technocratic meddling in developing countries at the local level

One of the readers of Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten has contributed a review of James Ferguson’s The Anti-Politics Machine. The reviewer looked at a few development economics stories that illustrate some of the more common problems western technocrats encounter when they provide their “expert advice” to people in developing countries. This is one of perhaps a dozen or so anonymous reviews that Scott publishes every year with the readers voting for the best review and the names of the contributors withheld until after the voting is finished:

But even if the project was in some sense a “failure” as an agricultural development project, it is indisputable that many of its “side effects” had a powerful and far-reaching impact on the Thaba-Tseka region. […] Indeed, it may be that in a place like Mashai, the most visible of all the project’s effects was the indirect one of increased Government military presence in the region

As the program continued to unfold, the development officials became more and more disillusioned — not with their own choices, but with the people of Thaba-Tseka, who they perceived as petty, apathetic, and outright self-destructive. A project meant to provide firewood failed because locals kept breaking into the woodlots and uprooting the saplings. An experiment in pony-breeding fell apart when “unknown parties” drove the entire herd of ponies off of cliffs to their deaths. Why, Ferguson’s official contacts bemoaned, weren’t the people of Thaba-Tseka committed to their own “development”?

Who could possibly be opposed to trees and horses? Perhaps, the practitioners theorized, the people of Thaba-Tseka were just lazy. Perhaps they “didn’t want to be better”. Perhaps they weren’t in their right mind or had made a mistake. Perhaps poverty makes a person do strange things.

Or, as Ferguson points out, perhaps their anger had something to do with the fact that the best plots of land in the village had been forcibly confiscated to make room for wood and pony lots, without any sort of compensation. The central government was all too happy to help find land for the projects, which they took from political enemies and put in the control of party elites, especially when it could use a legitimate anti-poverty program as cover. In Ferguson’s words, the development project was functioning as an “anti-politics machine” the government could use to pretend political power moves were just “objective” solutions to technical problems.

A local student’s term paper captured the general discontent:

In spite of the superb aim of helping the people to become self-reliant, the first thing the project did was to take their very good arable land. When the people protested about their fields being taken, the project promised them employment. […] It employed them for two months, found them unfit for the work, and dismissed them. Without their fields and without employment they may turn up to be very self-reliant. It is rather hard to know.

Two things stand out to me from this story. First, the “development discourse” lens served to focus the practitioners’ attention on a handful of technical variables (quantity of wood, quality of pony), and kept them from thinking about any repercussions they hadn’t thought to measure.

This is a serious problem, because “negative effects on things that aren’t your primary outcome” are pretty common in the development literature. High-paying medical NGOs can pull talent away from government jobs. Foreign aid can worsen ongoing conflicts. Unconditional cash transfers can hurt neighbors who didn’t receive the cash. And the literature we have is implicitly conditioned on “only examining the variables academics have thought to look at” — surely our tools have rendered other effects completely invisible!

Second, the project organizers somewhat naively ignored the political goals of the government they’d partnered with, and therefore the extent to which these goals were shaping the project.

Lesotho’s recent political history had been tumultuous. The Basotho Nationalist Party (BNP), having gained power upon independence in 1965, refused to give up power after losing the 1970 elections to the Basotho Congress Party (BCP). Blaming the election results on “communists”, BNP Prime Minister Leabua Jonathan declared a state of emergency and began a campaign of terror, raiding the homes of opposition figures and funding paramilitary groups to intimidate, arrest, and potentially kill anyone who spoke up against BNP rule.

This had significant effects in Thaba-Tseka, where “villages […] were sharply divided over politics, but it was not a thing which was discussed openly” due to a fully justified fear of violence. The BNP, correctly sensing the presence of a substantial underground opposition, placed “development committees” in each village, which served primarily as local wings of the national party. These committees spied on potential supporters of the now-outlawed BCP and had deep connections to paramilitary “police” units.

When the Thaba-Tseka Development Project started, its international backers partnered directly with the BNP leadership, reasoning that sustainable development and public goods provision could only happen through a government whose role they primarily viewed as bureaucratic. As a result, nearly every decision had to make its way through the village development committees, who used the project to pursue their own goals: jobs and project funds found their way primarily to BNP supporters, while the “necessary costs of development” always seemed to be paid by opposition figures.

The funding coalition ended up paying for a number of projects that reinforced BNP power, from establishing a new “district capital” (which conveniently also served as a military base) to constructing new and better roads linking Thaba-Tseka to the district and national capitals (primarily helping the central government tax and police an opposition stronghold). Anything that could be remotely linked to “economic development” became part of the project as funders and practitioners failed to ask whether government power might have alternate, more concerning effects.

As we saw earlier, the population being “served” saw this much more clearly than the “servants”, and started to rebel against a project whose “help” seemed to be aimed more at consolidating BNP control than meeting their own needs. When they ultimately resorted to killing ponies and uprooting trees, project officials infatuated with “development” were left with “no idea why people would do such a thing”, completely oblivious to the real and lasting harm their “purely technical decisions” had inflicted.

May 14, 2022

QotD: The farming cycle in pre-modern Mediterranean cultures

As you might imagine, time in agriculture is governed by the seasons. Crops must be planted at particular times, harvested at particular times. In most ancient societies, the keeping of the calendar was a religious obligation, a job for educated priests (either a professional priestly class as in the Near East, or local notables serving as amateurs, as in Greece and Rome).

The seasonal patterns vary a bit depending on the conditions and the sort of wheat being sown. In much of the Mediterranean, where the main concern was preserving a full year’s moisture for the crop, planting was done in autumn (November or October) and the crop was harvested in early summer (typically July or August). In contrast, the Han agricultural calendar for wheat planted in the spring, weeded over the summer and harvested in fall. The Romans generally kept to the autumn-planting schedule, except our sources note that on land which was rich enough (and wet enough) to be continuously cropped year after year (without a fallow), the crop was sown in spring; this might also be done in desperation if the autumn crop had failed. In Egypt, sowing was done as the Nile’s flood waters subsided at the beginning of Peret (in January), with the harvest taking place in Shemu (summer or early fall).

(As an aside on the seasons: we think in terms of four seasons, but many Mediterranean peoples thought in terms of three, presumably because Mediterranean winters are so mild. Thus the Greeks have three goddesses of the seasons initially, the Horae (spring, summer and fall) and Demeter’s grief divides the year into thirds not fourths in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. In ancient Egypt, there were three seasons: Akhet (Flood); Peret (Emergence [of fertile lands as the waters recede]) and Shemu (Low Water). The perception of the seasons depended on local climate and local cycles of agriculture.)

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part I: Farmers!”, A collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-24.

April 22, 2022

QotD: George Carlin’s appropriate-for-Earth-Day monologue

Let me tell you about endangered species, all right? Saving endangered species is just one more arrogant attempt by humans to control nature. It’s arrogant meddling. It’s what got us in trouble in the first place. Doesn’t anybody understand that? Interfering with nature. Over 90%, way over 90% of all the species that have ever lived on this planet, ever lived, are gone. They’re extinct. We didn’t kill them all. They just disappeared. That’s what nature does.

We’re so self-important. So self-important. Everybody’s going to save something now. “Save the trees, save the bees, save the whales, save those snails.” And the greatest arrogance of all: save the planet. What? Are these fucking people kidding me? Save the planet, we don’t even know how to take care of ourselves yet. We haven’t learned how to care for one another, we’re gonna save the fucking planet?

I’m getting tired of that shit. Tired of that shit. I’m tired of fucking Earth Day, I’m tired of these self-righteous environmentalists, these white, bourgeois liberals who think the only thing wrong with this country is there aren’t enough bicycle paths. People trying to make the world safe for their Volvos. Besides, environmentalists don’t give a shit about the planet. They don’t care about the planet. Not in the abstract they don’t. You know what they’re interested in? A clean place to live. Their own habitat. They’re worried that some day in the future, they might be personally inconvenienced. Narrow, unenlightened self-interest doesn’t impress me.

Besides, there is nothing wrong with the planet. Nothing wrong with the planet. The planet is fine. The PEOPLE are fucked. Difference. Difference. The planet is fine. Compared to the people, the planet is doing great. Been here four and a half billion years. Did you ever think about the arithmetic? The planet has been here four and a half billion years. We’ve been here, what, a hundred thousand? Maybe two hundred thousand? And we’ve only been engaged in heavy industry for a little over two hundred years. Two hundred years versus four and a half billion. And we have the CONCEIT to think that somehow we’re a threat? That somehow we’re gonna put in jeopardy this beautiful little blue-green ball that’s just a-floatin’ around the sun?

The planet has been through a lot worse than us. Been through all kinds of things worse than us. Been through earthquakes, volcanoes, plate tectonics, continental drift, solar flares, sun spots, magnetic storms, the magnetic reversal of the poles … hundreds of thousands of years of bombardment by comets and asteroids and meteors, worlwide floods, tidal waves, worldwide fires, erosion, cosmic rays, recurring ice ages … And we think some plastic bags, and some aluminum cans are going to make a difference? The planet … the planet … the planet isn’t going anywhere. WE ARE!

We’re going away. Pack your shit, folks. We’re going away. And we won’t leave much of a trace, either. Thank God for that. Maybe a little styrofoam. Maybe. A little styrofoam. The planet’ll be here and we’ll be long gone. Just another failed mutation. Just another closed-end biological mistake. An evolutionary cul-de-sac. The planet’ll shake us off like a bad case of fleas. A surface nuisance.

You wanna know how the planet’s doing? Ask those people at Pompeii, who are frozen into position from volcanic ash, how the planet’s doing. You wanna know if the planet’s all right, ask those people in Mexico City or Armenia or a hundred other places buried under thousands of tons of earthquake rubble, if they feel like a threat to the planet this week. Or how about those people in Kilauea, Hawaii, who built their homes right next to an active volcano, and then wonder why they have lava in the living room.

The planet will be here for a long, long, LONG time after we’re gone, and it will heal itself, it will cleanse itself, ’cause that’s what it does. It’s a self-correcting system. The air and the water will recover, the earth will be renewed, and if it’s true that plastic is not degradable, well, the planet will simply incorporate plastic into a new pardigm: the earth plus plastic. The earth doesn’t share our prejudice towards plastic. Plastic came out of the earth. The earth probably sees plastic as just another one of its children. Could be the only reason the earth allowed us to be spawned from it in the first place. It wanted plastic for itself. Didn’t know how to make it. Needed us. Could be the answer to our age-old egocentric philosophical question, “Why are we here?” Plastic … asshole.

So, the plastic is here, our job is done, we can be phased out now. And I think that’s begun. Don’t you think that’s already started? I think, to be fair, the planet sees us as a mild threat. Something to be dealt with. And the planet can defend itself in an organized, collective way, the way a beehive or an ant colony can. A collective defense mechanism. The planet will think of something. What would you do if you were the planet? How would you defend yourself against this troublesome, pesky species? Let’s see … Viruses. Viruses might be good. They seem vulnerable to viruses. And, uh … viruses are tricky, always mutating and forming new strains whenever a vaccine is developed. Perhaps, this first virus could be one that compromises the immune system of these creatures. Perhaps a human immunodeficiency virus, making them vulnerable to all sorts of other diseases and infections that might come along. And maybe it could be spread sexually, making them a little reluctant to engage in the act of reproduction.

Well, that’s a poetic note. And it’s a start. And I can dream, can’t I? See I don’t worry about the little things: bees, trees, whales, snails. I think we’re part of a greater wisdom than we will ever understand. A higher order. Call it what you want. Know what I call it? The Big Electron. The Big Electron … whoooa. Whoooa. Whoooa. It doesn’t punish, it doesn’t reward, it doesn’t judge at all. It just is. And so are we. For a little while.

George Carlin, “The arrogance of mankind”.