Train of Thought

Published 5 May 2023In today’s video, we take a look at the American Orient Express, an attempt made by several businesses to replicate the charm and appeal of the real deal that just kept running into bad luck.

(more…)

August 5, 2023

The rotten luck of the American Orient Express

August 2, 2023

How Shipping Containers Took Over the World (then broke it)

Calum

Published 5 Oct 2022The humble shipping container changed our society — it made International shipping cheaper, economies larger and the world much, much smaller. But what did the shipping container replace, how did it take over shipping and where has our dependance on these simple metal boxes led us?

(more…)

July 26, 2023

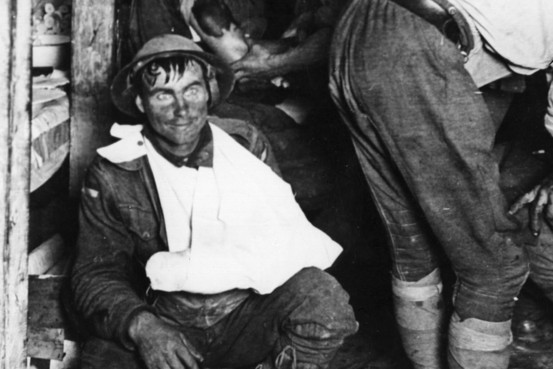

Bombing France into Freedom – War Against Humanity 105

World War Two

Published 25 Jul 2023The destruction of German cities has shown how difficult it is for the heavy bombers of the RAF and USAAF to hit small targets with precision. Things will be no different when these big beasts go into action to support the D-Day landings. Thousands of French civilians will pay the price for the flawed logic of Allied bombing.

(more…)

July 25, 2023

WWI Footage: Narrow Gauge Train Lines in France

Charlie Dean Archives

Published 14 Aug 2013American forces constructing railways throughout France to help move men and supplies during World War One. We see US Army personnel laying the sleepers and track for the extensive network of two foot (60cm) narrow gauge lines, ballasting work, loading and laying of pre-built trackwork. We also see scenes of the railway in action as the little trains trundle along country lanes and through the town streets. The film ends with scenes of the train taking soldiers towards the front lines.

After the war the lines were abandoned and most of the locomotives and rollingstock simply left where they were last used, with many being salvaged by the locals to help with logging activities.

CharlieDeanArchives – Archive footage from the 20th century making history come alive!

July 11, 2023

What is a HUMP Yard?

V12 Productions

Published 24 Oct 2022Hump yards are amazing pieces of engineering that allow railroads to use gravity to sort cars and build trains. Of course, not all railroad equipment can be humped.

(more…)

July 9, 2023

Grain Elevator

NFB

Published 30 Sept 2015This documentary short is a visual portrait of “Prairie Sentinels”, the vertical grain elevators that once dotted the Canadian Prairies. Surveying an old diesel elevator’s day-to-day operations, this film is a simple, honest vignette on the distinctive wooden structures that would eventually become a symbol of the Prairie provinces.

(more…)

July 4, 2023

Buster Keaton Rides Again (1965)

NFB

Published 15 Jun 2015In this film Keaton rides across Canada on a railway scooter and, between times, rests in a specially appointed passenger coach where he and Mrs. Keaton lived during their Canadian film assignment. This film is about how Buster Keaton made a Canadian travel film, The Railrodder. In this informal study the comedian regales the film crew with anecdotes of a lifetime in show business. Excerpts from his silent slapstick films are shown

Directed by John Spotton – 1965.

May 15, 2023

Every Detail of Grand Central Terminal Explained | Architectural Digest

Architectural Digest

Published 6 Jun 2018Historian and author Anthony W. Robins and journalist Sam Roberts of the New York Times guide Architectural Digest through every detail of Grand Central Terminal. Our narrators walk us through the legendary structure from the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Foyer through Vanderbilt Hall to the main concourse (and the famous four-faced clock). From there, we learn more about the underground walkways, whispering gallery, Oyster Bar restaurant, Campbell Apartment, Pershing Square, and more.

(more…)

May 6, 2023

Coronation Weekend

Jago Hazzard

Published 5 May 2023For us train nerds, “Coronation” means something very different.

May 4, 2023

Why British train enthusiasts hate this man – Dr. Beeching’s Railway Axe

Train of Thought

Published 27 Jan 2023In today’s video, we take a look at one Doctor Richard Beeching, the man who ripped up a third of Britain’s railways with nothing but a pen and paper.

April 22, 2023

The Big Four

Jago Hazzard

Published 1 Jan 2023It’s 100 years since the Grouping – what happened, why and how?

(more…)

April 13, 2023

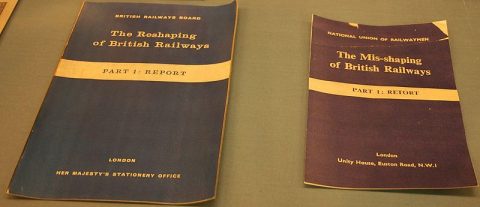

Beeching plus 60

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams notes that it’s just past 60 years since one of the most controversial documents the British government published during the latter half of the 20th century: The Beeching Report.

The British Railways Board’s publication The Reshaping of British Railways, Part 1: Report, Beeching’s first report, which famously recommended the closure of many uneconomic British railway lines. Many of the closures were implemented. This copy is displayed at the National Railway Museum in York beside a copy of the National Union of Railwaymen’s published response, The Mis-shaping of British Railways, Part 1: Retort.

Photo by RobertG via Wikimedia Commons.

Wednesday, 27 March 1963 marked the day when a civil servant with a doctorate in physics, seconded from ICI, proudly flourished a report he had written. That man was Dr Richard Beeching, and the result of his recommendations contained in The Reshaping of British Railways are with us to this day.

Beeching identified many unprofitable rail services and suggested the widespread elimination of a huge number of routes. He identified 2,363 stations for closure, along with 6,000 miles of track — a third of the existing network — with the loss of 67,700 jobs. His stated aim was to prune the railway system back into a profitable concern. Behind Beeching, seconded to the newly-established British Railways Board, stood the figure of the publisher-turned-Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan. He knew a thing or two about railways, having been a pre-nationalisation director of the Great Western Railway. It put him in the delightful position of never having to pay for a train ticket.

Macmillan observed from a shareholder’s point of view, “you can pour all in money you want, but you can never make the damned things pay for themselves”. In his view, the railway network and infrastructure of wagon works, tiny branch lines, cottages for signallers, crossings keepers and station masters, with most halts staffed 18 hours a day, amounted to a social service, albeit an expensive one. It had made the prosperity of Victorian Britain possible and was sustaining it still. From nationalisation in 1948, the railways themselves had attempted to make savings, closing 3,000 miles of track and reducing staff from 648,000 to 474,000. That famous Ealing comedy film of 1953, The Titfield Thunderbolt, about a group of villagers trying to keep their branch line operating after British Railways decided to close it, already reflected concern and railway nostalgia.

Britain’s literary and celluloid love affair with iron rails and steam began as long ago as 1905 with the publication of Edith Nesbit’s The Railway Children, a success which peaked when the book was made into a highly successful movie in 1970. Meanwhile, professional sleuths and loafers like Sherlock Holmes, Bulldog Drummond, Lord Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot and Bertie Wooster capitalised on the branch line network in their methodology of moving swiftly about pastoral England in their hunts for miscreants. It was the success of The Lady Vanishes, a 1938 mystery thriller set on a continental train, that launched Alfred Hitchcock as a world-class director. David Lean’s Brief Encounter of 1945, based on Noël Coward’s earlier one-act play, Still Life, attached deep romance to station platforms and waiting rooms, reminiscent of so much heartache in the recently fought world war. It is still regarded as one of the greatest of all British-made films. None of this mattered to Beeching, the man who was “Britain’s most-hated civil servant” at his death in 1985, a moniker still used today.

There’s an argument that Beeching was deliberately set up as a patsy for the real villains, Ernest Marples and Harold MacMillan:

The cold, dispassionate Beeching was absolutely the wrong man for the job. As he told the Daily Mirror at the time, “I have no experience of railways, except as a passenger. So, I am not a practical railwayman. But I am a very practical man.” John Betjeman, writing persuasively and eloquently in the Daily Telegraph each week, and later Ian Hislop, hit the right note in observing that Beeching, and all he stood for were technocrats. They “weren’t open to arguments of romantic notions of rural England, or the warp-and-weft of the train in our national identity. They didn’t buy any of that, and went for a straightforward profit and loss approach, from which we are still reeling today”.

However, it has also been argued that Beeching was the unwitting fall-guy for the Minister of Transport of the day, Ernest Marples. He was a self-made businessman who “got things done”, but he retained an air of shadiness about him. Macmillan should have known better. Marples had been managing director of Marples Ridgway, awarded contracts to build the first motorways. When challenged about a conflict of interest, he sold his 80 per cent shareholding to his wife. Elevated to the peerage, Marples fled to Monaco in 1975 to avoid prosecution for tax fraud. So, in some ways, the thing was a stitch-up. Marples directly benefited from the widespread cuts advocated by his subordinate, Beeching. Macmillan had his eye off the ball and was already considering retirement, hastened by an operation for prostate cancer six months after Beeching’s report.

The Prime Minister was astute enough to ensure the press presented the cuts in a positive way, however. From the Cabinet papers of the day, we now know the day before the publication of The Reshaping of British Railways, Beeching’s findings were rewritten to suggest the cuts were the first phase of a co-ordinated national transport policy, with advanced plans to replace the axed rail networks with improved minor roads and local bus services. In reality this was political fantasy (my inner lawyer cautions against more extremist language), for the bus-road subsidy would have cost more than that already paid to the railways. The promise of replacement bus services should have come with a guarantee of remaining in place for at least 10-15 years, because most were withdrawn after two, forcing more motor traffic onto an already inadequate road network.

April 12, 2023

Miniature Railway (1959)

British Pathé

Published 13 Apr 2014Romney, Kent.

L/S of a lovely looking train locomotive. A man stands next to it and one realises how small the train is. It is one third of an ordinary train size — says voiceover. However, this is not a toy but a regular public railway, smallest in the world. It is officially known as the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, it runs between Romney and Dungeness and its passengers are children. This tiny railway must conform to the same Ministry of Transport regulations as any other trains. M/S of a driver Mr Bill Hart, checking the train. C/U shot of a plaque reading “Winston Churchill”. This is the engine’s name. Several shots of Mr Hart checking the train. Mr Hart enters his cabin and starts shovelling coal into the boiler. C/U shot of the coal being thrown in and a little door closed. This train takes one third of the coal needed for a regular size train. The train starts moving.

L/S of the two men turning locomotive on turntable to place it on rails. M/S of a woman cleaning windows along the train. Children arrive and station master, Reg Marsh, directs them to their coaches. M/S of the group of girls entering the train. M/S of the station master Mr Marsh blowing a whistle as a sign that train leaves the station. M/S of an elderly man looking at a huge pocket watch on a chain, and afterwards, in direction of the train. He is Captain Howey, a man responsible for having the line built. C/U shot of the watch — Roman numerals. M/S of Mr Howey as he puts the watch in his pocket. C/U shot of Mr Howey’s face.

M/S of the little train moving. C/U shot of its little chimney with a smoke coming out. M/S of the Rose family from Sanderstead, Surrey with their dog Trixie enjoying the ride C/U shot of driver’s face with the smoke covering it up to the point it becomes invisible. Another little train passes it going in different direction. Several shots of the two little trains moving. A car stops to wait for the train to pass. L/S of the little train as it approaches the station.

Note: Another driver appearing in the film is Peter Catt. Combined print for this story is missing.

(more…)

March 24, 2023

From “railway spine” to “shell shock” to PTSD

At Founding Questions, Severian discusses how our understanding of what we now label “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” evolved from how doctors visualized bodily ailments over a century ago:

I mentioned “shell shock” yesterday, so let’s start there. Medicine in 1914 was still devoted to the “Paris School,” which assumed nothing but organic etiology for all syndromes. Sort of a reverse Descartes — as Descartes (implicitly) “solved” the mind-body problem by disregarding the body, so the “Paris School” of medicine solved it by disregarding the mind. So when soldiers started coming back from the front with these bizarre illnesses, naturally doctors began searching for an organic cause. (That’s hardly unique to the Paris School, of course; I’m giving you the context to be fair to the 1914 medical establishment, whose resistance to psychological explanations otherwise seems so mulish to us).

They’d noticed something similar in the late 19th century, with industrial accidents and especially train crashes. When a train crashed, the people in the first few cars were killed outright, those in the next few wounded, but the ones in the back were often physically fine. But within a few hours to weeks, they started exhibiting all kinds of odd symptoms. Hopefully you’ve never been in a train crash, but if you’ve ever been in a fender-bender you’ve no doubt experienced a minor league version of this.I hit a deer on the highway once. Fortunately I was at highway speed, and hit it more or less dead on (it jumped out as if it were committing suicide), so it got thrown away from the car instead of coming through the windshield. The car’s front end was wrecked, naturally, but I was totally fine. I don’t think the seatbelt lock even engaged, much less the airbag, since I didn’t even have time to hit the brakes.

The next few hours to days were interesting, physiologically. It felt like my body was playing catch up. I had an “oh shit, I’m gonna crash!!!” reaction about 45 minutes after I’d pulled off to the side of the road, duct-taped the bumper back on as best I could, and continued to my destination. All the stuff I would have felt had I seen the deer coming came flooding in. Had I not already been where I was going, I would’ve needed to pull over, because that out of the blue adrenaline hit had my hands shaking, and my vision fuzzed out briefly.

The next morning I was sore. I had all kinds of weird aches, as if I’d just played a game of basketball or something. I assume part of it actually was the impact — it didn’t feel like much in the moment, but if it’s enough to crumple your car’s front end (and it was trashed), it’s enough to give you a pretty good jolt. That would explain soreness in the arms, elbows, and shoulders — a stiff-armed, white-knuckle grip on the steering wheel, followed by a big boom. But I was also just kinda sore all over, plus this generalized malaise. I felt not-quite-right for the next few days. Nothing big, no one symptom I can really put my finger on, but definitely off somehow — a little twitchy, a little jumpy, and really tired.

Having done my WWI reading, I knew what it was, and that’s when I really understood the doctors’ thought processes. I really did take some physical damage, because I really did receive a pretty good full-body whack. It just wasn’t obvious to the naked eye. And since everyone has experienced odd physical symptoms from being rattled around, or even sleeping on a couch or sprung mattress, it makes sense — the impact obviously jiggled my spine, which probably accounts for a great many of the physical symptoms. Hence, “railway spine”. And from there, “shell shock” — nothing rattles your back like standing in a trench or crouching in a dugout as thousands of pounds of high explosive go off around you. It must be like going through my car crash all day, every day.

Skip forward a few decades, and we now have a much better physiological understanding of what we now call (and I will henceforth call) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). There’s a hypothesis that I personally believe, that “shell shock” is also a whole bunch of micro-concussions as well as “classic” PTSD, but let’s leave that aside for now. The modern understanding of PTSD is largely about chemistry. Cortisol and other stress chemicals really fuck you up. They have systemic physical and mental effects. If those chemicals don’t get a chance to flush out of your system — if you’re in a trench for weeks on end, let’s say — the effects are cumulative, indeed exponential.

Returning to my car crash: I was “off” for a few days because my body got a huge jolt of stress chemicals. That odd not-quite-right thing I felt was those chemicals flushing through. Had I gone to a shrink at that moment, he probably would’ve diagnosed me with PTSD. But I didn’t have PTSD. I had a perfectly normal physiological reaction to a big shot of stress chemicals. If I’d gotten into car crash after car crash, though, day in and day out, that would’ve been PTSD. I’d be having nightmares about that deer every night, instead of just the once. And all that would have cumulative, indeed exponential, effects.

He then goes on to cover similar physical reactions to stimuli in modern life, so I do recommend you RTWT.

February 28, 2023

The strange Steam Locomotive that was built like a Diesel – SR Leader Class

Train of Thought

Published 4 Nov 2022In today’s video, we take a look at the Southern Railway “Leader” locomotive that was built like a diesel, powered by steam and had a lot pros and cons.

(more…)