When asked about Machiavelli’s reputation, people use terms like “amoral”, “cynical”, “unethical”, or “unprincipled”. But this is incorrect. Machiavelli did believe in moral virtues, just not Christian or Humanistic ones.

What did he actually believe?

In 1953, the British philosopher Isaiah Berlin delivered a lecture titled “The Originality of Machiavelli”.

Berlin began by posing a simple question: Why has Machiavelli unsettled so many people over the years?

Machiavelli believed that the Italy of his day was both materially and morally weak. He saw vice, corruption, weakness, and, as Berlin says, “lives unworthy of human beings”. It’s worth noting here that around the time that Machiavelli died in 1527, the Age of Exploration was just kicking off, and adventurers from Italy and elsewhere in Europe were in the process of transforming the world. Even the shrewdest individuals aren’t always the best judges of their own time.

So what did Machiavelli want? He wanted a strong and glorious society. Something akin to Athens at its height, or Sparta, or the kingdoms of David and Solomon. But really, Machiavelli’s ideal was the Roman Republic.

To build a good state, a well-governed state, men require “inner moral strength, magnanimity, vigour, vitality, generosity, loyalty, above all public spirit, civic sense, dedication to security, power, glory”.

According to Machiavelli, these are the Roman virtues.

In contrast, the ideals of Christianity are “charity, mercy, sacrifice, love of God, forgiveness of enemies, contempt for the goods of this world, faith in the hereafter”.

Machiavelli wrote that one must choose between Roman and Christian virtues. If you choose Christianity, you are selecting a moral framework that is not favorable to building and preserving a strong state.

Machiavelli does not say that humility, compassion, and kindness are bad or unimportant. He actually agrees that they are, in fact, good and righteous virtues. He simply says that if you adhere to them, then you will be overrun by more unscrupulous men.

In some instances, Machiavelli would say, rulers may have to commit war crimes in order to ensure the survival of their state. As one Machiavelli translator has put it: “Men cannot afford justice in any sense that transcends their own preservation”.

From Berlin’s lecture:

If you object to the political methods recommended because they seem to you morally detestable … Machiavelli has no answer, no argument … But you must not make yourself responsible for the lives of others or expect good fortune; you must expect to be ignored or destroyed.

In a famous passage, Machiavelli writes that Christianity has made men “weak”, easy prey to “wicked men”, since they “think more about enduring their injuries than about avenging them”. He compares Christianity (or Humanism) unfavorably with Paganism, which made men more “ferocious”.

“One can save one’s soul,” writes Berlin, “or one can found or maintain or service a great and glorious state; but not always both at once.”

Again, Machiavelli’s tone is descriptive. He is not making claims about how things should be, but rather how things are. Although it is clear what his preference is.

He writes that Christian virtues are “praiseworthy”. And that it is right to praise them. But he says they are dead ends when it comes to statecraft.

Machiavelli wrote:

Any man who under all conditions insists on making it his business to be good, will surely be destroyed among so many who are not good. Hence a prince … must acquire the power to be not good, and understand when to use it and when not to use it, in accord with necessity.

To create a strong state, one cannot hold delusions about human nature:

Everything that occurs in the world, in every epoch, has something that corresponds to it in the ancient times. The reason is that these things were done by men, who have and have always had the same passions.

Rob Henderson, “The Machiavellian Maze”, Rob Henderson’s Newsletter, 2023-12-09.

March 12, 2024

QotD: Isaiah Berlin on Niccolò Machiavelli

March 10, 2024

German Blunder Hands Allies a Rhine Crossing – WW2 – Week 289 – March 9, 1945

World War Two

Published 9 Mar 2024The Allies manage to take an intact bridge over the mighty Rhine at Remagen, a major piece of luck; the Germans launch a new offensive in Hungary, and the Allies end one in Italy. Over in Burma, Meiktila falls, sabotaging the entire Japanese supply system for the country, and on Iwo Jima the fight continues, bloodier than ever for both sides.

00:59 Recap

01:35 The Fall of Meiktila

03:46 The fight on Iwo Jima

05:27 Advances on the Western Front

07:44 The Rhine River

10:05 Remagen Bridge

16:20 Operation Encore

17:10 Rokossovsky and Zhukov attack

18:09 Operation Spring Awakening

21:57 Notes to end the week

23:42 Conclusion

(more…)

March 9, 2024

The Jewish Avengers Who Hunted Nazi Murderers

World War Two

Published Mar 8, 2024In March 1945, the first Jewish unit in the Allied forces reaches the frontline. Before fighting the Nazis, the men spent years battling against the policies of the British government. After the war, they will take vengeance on the perpetrators of the Holocaust and join the Zionist movement in building and fighting for Israel.

(more…)

February 26, 2024

Rome: Part 4 – The First Punic War 264-241 BC

seangabb

Published Feb 25, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

• Growth of Tensions between Rival Powers

• Differences of Civilisation

• The Outbreak of War

• The Course of War

• Growth of Roman Sea Power

• The End and Significance of the War

(more…)

February 25, 2024

Iwo Jima! – WW2 – Week 287 – February 24, 1945

World War Two

Published 24 Feb 2024This week the Battle of Iwo Jima begins and American forces raise the Stars and Stripes on Mount Suribachi. Elsewhere, the Allies fight the stiff Japanese defences in Manila. The Red Army continues fighting through East Prussia and Pomerania as Stalin plans the next stage of the advance on the Reich. There are Allied advances in Western Europe and Italy too.

00:01 Intro

00:54 Recap

01:16 Iwo Jima Begins

06:32 The war in the Philippines

07:56 The Battle of Manila

11:12 Fighting in Burma

12:14 Operation Grenade

13:46 Operation Encore

14:38 Soviet plans for new offensives

21:28 Moscow Commission Meets

(more…)

February 21, 2024

“There’s a moral imperative to go dig out that villa … It could be the greatest archaeological treasure on earth”

In City Journal, Nicholas Wade discusses the technical side of the ongoing attempts to read one of the Herculaneum scrolls:

A computer scientist has labored for 21 years to read carbonized ancient scrolls that are too brittle to open. His efforts stand at last on the brink of unlocking a vast new vista into the world of ancient Greece and Rome.

Brent Seales, of the University of Kentucky, has developed methods for scanning scrolls with computer tomography, unwrapping them virtually with computer software, and visualizing the ink with artificial intelligence. Building on his methods, contestants recently vied for a $700,000 prize to generate readable sections of a scroll from Herculaneum, the Roman town buried in hot volcanic mud from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.

The last 15 columns — about 5 percent—of the unwrapped scroll can now be read and are being translated by a team of classical scholars. Their work is hard, as many words are missing and many letters are too faint to be read. “I have a translation but I’m not happy with it,” says a member of the team, Richard Janko of the University of Michigan. The scholars recently spent a session debating whether a letter in the ancient Greek manuscript was an omicron or a pi.

[…]

Seales has had to overcome daunting obstacles to reach this point, not all of them technical. The Italian authorities declined to make any of the scrolls available, especially to a lone computer scientist with no standing in the field. Seales realized that he had to build a coalition of papyrologists and conservationists to acquire the necessary standing to gain access to the scrolls. He was eventually able to x-ray a Herculaneum scroll in Paris, one of six that had been given to Napoleon. To find an x-ray source powerful enough to image the scroll without heating it, he had to buy time on the Diamond particle accelerator at Harwell, England.

In 2009, his x-rays showed for the first time the internal structure of a scroll, a daunting topography of a once-flat surface tugged and twisted in every direction. Then came the task of writing software that would trace the crumpled spiral of the scroll, follow its warped path around the central axis, assign each segment to its right position on the papyrus strip, and virtually flatten the entire surface. But this prodigious labor only brought to light a more formidable problem: no letters were visible on the x-rayed surface.

Seales and his colleagues achieved their first notable success in 2016, not with Napoleon’s Herculaneum scroll but with a small, charred fragment from a synagogue at the En-Gedi excavation site on the shore of the Dead Sea. Virtually unwrapped by the Seales software, the En-Gedi scroll turned out to contain the first two chapters of Leviticus. The text was identical to that of the Masoretic text, the authoritative version of the Hebrew Bible — and, at nearly 2,000 years old, its earliest instance.

The ink used by the Hebrew scribes was presumably laden with metal, and the letters stood out clearly against their parchment background. But the Herculaneum scroll was proving far harder to read. Its ink is carbon-based and almost impossible for x-rays to distinguish from the carbonized papyrus on which it is written. The Seales team developed machine-learning programs — a type of artificial intelligence — that scanned the unrolled surface looking for patterns that might relate to letters. It was here that Seales found use for the fragments from scrolls that earlier scholars had destroyed in trying to open them. The machine-learning programs were trained to compare a fragment holding written text with an x-ray scan of the same fragment, so that from the statistical properties of the papyrus fibers they could estimate the probability of the presence of ink.

February 20, 2024

Rome: Part 3 – The Expansion of Roman Power

seangabb

Published Feb 18, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 3: The Expansion of Roman Power

• The Conquest of Central Italy

• The Gallic Sack of 390 BC

• The Conquest of the Greek Cities

• Relations with Carthage

(more…)

February 17, 2024

Breda 37: Italy’s Forgotten Heavy Machine Gun

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 11, 2023The Breda Model 37 was Italy’s standard heavy machine gun (which meant a rifle-caliber gun fired only from a tripod) during World War Two. It was chambered for the 8x59mm cartridge, as Italy used a two-cartridge system at the time, with 6.5mm for rifles and the heavier 8mm for machine guns to exploit their longer effective range. Production began in 1937 and continued until the end of the war, with a batch being made for German use after the Italian armistice in 1943. Pre-war it was also sold to Portugal as the m/938. It remained in Italian use after the war as well, eventually replaced by the MG42/59.

The Breda 37 is a durable, reliable, and overall very good design. It uses 20-round feed strips, with the quite unusual feature of placing fired cases back into the strips rather than ejecting them out of the gun. It is a relatively unknown gun today, but this is not because of any inferiority on its part.

(more…)

February 15, 2024

Artillery! A WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 14 Feb 2024The modern artillery of the Great War was responsible for the vast majority of military deaths in that conflict, but how has artillery developed from that war to this one? Today we take a look at some of the artillery of WW2.

(more…)

The Big Picture – NATO: Partners in Peace (1954)

Army University Press

Published Nov 13, 2023NATO: Partners in Peace follows the creation and impact of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Created in April 1949 with twelve founding members, this organization’s goal was to protect the inherent rights of individual states through collective defense. In this episode from The Big Picture series, General Dwight D. Eisenhower offers a speech before he deploys to Europe to become the first Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). This is followed with footage of the buildup and training of European forces. Once Eisenhower leaves NATO to campaign for the presidency, General Matthew Ridgway replaces him as NATO commander. One significant problem NATO forces faced was the fact that each nation had its own weapon systems and ammunition, an issue the U.S. wanted to address with the standardization of the 7.62mm cartridge. Perhaps as a deterrent to the Soviet Union, NATO: Partners in Peace depicts new weapons that could be used against a large enemy force such as remote-controlled missiles, napalm bombs, and the massive atomic cannon.

February 9, 2024

Rome: Part 2 – Consolidation of the Republic

seangabb

Published Feb 8, 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 2: Consolidation of the Republic

• The Roman Revolution against the Kings

• How Brutus put his own sons to death

• How Horatius kept the Bridge

• Scaevola and Lars Porsena

• The Roman Constitution: an Overview

(more…)

The (so-far limited) ability to read the Herculaneum Papyri may vastly increase our knowledge about the Roman world

Colby Cosh on the achievement of the three young researchers who were awarded the Vesuvius Challenge prize earlier this month, and what it might mean for classicists and other academics:

On Monday morning, Farritor and two other young Vesuvius Challenge notables, Youssef Nader and Julian Schillinger, were announced as winners of the grand prize. Nader and Schillinger had, like Farritor, already won Vesuvius Challenge prizes for smaller technical discoveries, and Nader had in fact been a mere heartbeat behind Farritor in producing the same “porphyras” from the same scan. After Farritor nabbed his US$40,000 “first letters” prize, the three decided to combine their efforts to net the big fish.

The result is a text that represents about five per cent of one of the thousands of scrolls recovered — and there may be more not yet recovered — from the Villa of the Papyri. The enormous villa was owned by an unknown Roman notable, but there are clues that one of its librarians was the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, who lived from around 110 to 35 BC. Until his identity was connected with the library, Philodemus did not receive too much attention even from classicists. But the Vesuvius Challenge efforts have now yielded fragments of what has to be an Epicurean text — one which discusses the delights of music and food, and condemns an unnamed adversary, possibly a Stoic, for failing to give a philosophical account of sensual pleasure.

The recovery of dozens more of the works of Philodemus would be — one might now say “will be” — a world-changing event for the classics. We know Philodemus was close to Calpurnius Piso (101-43 BC), the father-in-law of Julius Caesar and a likely owner of the doomed villa. He almost certainly had a front-row seat for the prelude to the end of the Roman Republic. We know he wrote works on religion, on natural philosophy and on history: even his thoughts on music and poetry would be of marked interest.

But nobody knows what else, what copies of older works, may be lurking in Philodemus’s library. At this moment antiquarians know the titles of dozens of lost plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles and Euripides and Aristophanes; we are missing major works of Aristotle and Euclid and Archimedes and Eratosthenes. We know that Sulla wrote his memoirs and that Cato the Elder wrote a seven-book history of Rome. Any of these old writings, or others of equal significance, may materialize suddenly out of oblivion now, thanks to the Vesuvius Challenge. It’s an impressive triumph for the idea of prize-giving as an approach to solving scientific problems, and the news release from the challenge offers a discussion of what the funding team got right and where the project will go next.

February 8, 2024

Beretta 1915: The first of the Beretta pistols

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jun 22, 2016The Italian military went into WWI having already adopted a semiautomatic sidearm — the Model 1910 Glisenti (and its somewhat simplified Brixia cousin). However, the 1910 Glisenti was a very complex design, and much too expensive to be practical for the needs of the global cataclysm that was the Great War. In response to a need for something cheaper, Tulio Marengoni of the Beretta company designed the Model 1915, a simple blowback handgun chambered for the 9mm Glisenti cartridge.

Only 15,300 of the Model 1915 pistol were made, because even they proved to be a bit more than the military really needed. One of their most interesting mechanical features is a pair of manual safeties — one on the back of the frame to lock the hammer and one on the left side to block the trigger. This proved a bit redundant, and the gun overall was rather large and heavy. In 1917 a scaled-down version in .32 ACP (7.65mm) was introduced which would be produced in much larger numbers. The 1915/17 would also omit the rather unnecessary hammer safety.

It is important to note that while the 9mm Glisenti cartridge is dimensionally interchangeable with 9×19 Parabellum, pistols designed for the Glisenti cartridge should never be used with standard 9×19 ammunition, as it is nearly 50% more powerful than the Glisenti specs, and doing so will quickly cause damage (and potentially catastrophic failure).

February 5, 2024

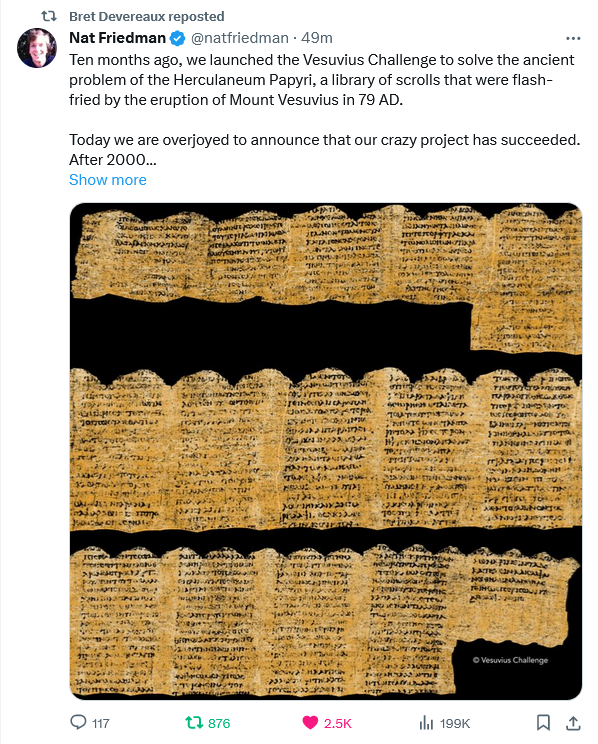

The Vesuvius Challenge prize has been awarded!

Scrolling through Twit-, er, I mean “X” this morning brought me this amazing piece of news for classical scholars:

We received many excellent submissions for the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize, several in the final minutes before the midnight deadline on January 1st.

We presented these submissions to the review team, and they were met with widespread amazement. We spent the month of January carefully reviewing all submissions. Our team of eminent papyrologists worked day and night to review 15 columns of text in anonymized submissions, while the technical team audited and reproduced the submitted code and methods.

There was one submission that stood out clearly from the rest. Working independently, each member of our team of papyrologists recovered more text from this submission than any other. Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing the Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85% of characters recoverable. This was not a given: most of us on the organizing team assigned a less than 30% probability of success when we announced these criteria! And in addition, the submission includes another 11 (!) columns of text — more than 2000 characters total.

The results of this review were clear and unanimous: the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize of $700,000 is awarded to a team of three for their excellent submission. Congratulations to Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger!

Much more information at the Vesuvius Challenge site.

February 1, 2024

Rome: Part 1 – Mythical Origins to the Founding of the Republic

seangabb

Published 31 Jan 2024This course provides an exploration of Rome’s formative years, its rise to power in the Mediterranean, and the exceptional challenges it faced during the wars with Carthage.

Lecture 1: Mythical Beginnings and the Founding of Rome (753 BC – 509 BC)

• What is said by the archaeology and modern research on the origins of Rome

• The lack of authentic literary history of Rome in its early period

• Legend of Romulus and Remus

• The establishment of Rome’s early monarchy

• Transition to the Roman Republic

(more…)