A few years ago, I was called upon to inform the IRS that a former employee of mine would have liked to be paid more than I had paid him. Given that I have never met a freelance writer who thought he was being paid enough, I thought it a strange request, but I eventually understood the IRS’s line of thinking: The gentleman in question, who was in his 80s at the time, had retired from his former occupation and worked as a freelance writer. His beat involved a great deal of travel, and he deducted the expenses for which he was not compensated — which, the state of the newspaper industry being what it is, was all of them, at least as far as my editorial budget was concerned. The IRS suspected that his writing gig was somehow phony, something he had invented simply for tax deductions. In truth, he was just a freelance writer who didn’t make a lot of money — i.e., a freelance writer indistinguishable from about 88.8 percent of all freelance writers.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Mottos for Miscreants”, National Review, 2014-11-20.

December 10, 2015

QotD: Freelance writing

December 3, 2015

Medical charities and their prime mission

David Warren is rather a skeptic on the long-term usefulness of big medical charities (and not just because, like any big bureaucracy, sooner or later the primary goal becomes for the organization itself to survive and grow rather than pursuing whatever they were originally created to do):

Medical “research” does similar direct damage. Huge foundations are created to “fight” every imaginable human ailment, and find new ones on which to build fresh fundraising efforts, should any of the old ones go stale. Grand sums are expended on “public awareness” campaigns, to encourage hypochondria and psychosomatic disorders. (I suspect, for instance, that the chief cause of lung cancer today is grisly health warnings on packets of cigarettes.) Money is raised in billions to “find a cure” for whatever. (Snake oil sales were on a much smaller scale.)

At the most elementary level, people should try to understand cause and effect. Vast numbers come to rely upon the metastasis of these soi-disant “charitable” bureaucracies. And if a cure is ever found, they will all be out of their overpaid jobs. Moreover, it is almost invariably some isolated, eccentric, unqualified and unfunded tyro, who makes the fatal discovery. That is why one of the principal tasks of any large medical foundation is to locate these brilliant “inventor” types, and sue them into surrender.

Does gentle reader know that almost all the increase in human longevity, over the last century or so, can be attributed to people washing their hands and taking showers? And most of the rest to better sewage disposal? Or that it took until almost the middle of the last century for life expectancy in the West to rise to levels last seen in the parish records of the Middle Ages? Which was when “modern” hygienic practices were last observed. (Large, centralized hospitals are the most efficient spreaders of infection today.)

Painkillers are nice, and I’m inclined to keep them, only if we realize that the blessing is mixed. They turn our minds away from futurity; they displace faith in God, to faith in doctors. They create the mindset that embraces “euthanasia.”

Of course, the main focus of contemporary liberal “philanthropy” is not on saving lives at all; rather on killing off babies — in Africa, by first choice. It is what the proggies used to call “population control,” until they invented better euphemisms. That is what truly gladdens the peons in the foundations of all the Bills and Melindas; and lights the corridors of the United Nations. That and the (still historically recent) “climate change” agenda.

November 25, 2015

Food labelling laws and craft brewing … not a match made in heaven

Eric Boehm on how well-intentioned laws can still have significant and unforeseen negative side-effects:

Brewers are facing the prospect of spending potentially thousands to determine calorie counts for every variety of beer produced. Unless they spend the money to provide the information, breweries may never get their products into chain restaurants, like Buffalo Wild Wings and Applebee’s.

As is often the case with regulations, smaller breweries stand to lose the most.

“A regional craft brewer or a major brewery can spread the cost over a much larger volume of sales and it’s not so unreasonable for them,” said Paul Gatza, a former brewer who now heads the Boulder, Colorado, based Brewers’ Association, an industry group.

“Smaller guys that are just trying to sell a keg or two here or there, they have a decision to make on whether it is worth the additional cost to try to get their beers into chain restaurants,” Gatza told Watchdog.

The Food and Drug Administration is in the process of finalizing menu labeling rules that were part of the Affordable Care Act. Intended to make Americans more aware of their dietary choices, the rules are subject to controversy on several fronts, and the FDA announced in September that implementation of the new rules would be pushed back one full year, until December 2016, as the feds try to work out the kinks.

My favourite local brewery isn’t even a micro-brewery (they’re somewhere between a pico- and a nano-brewery): every week when I drop in, there are three or four new batches ready to sample (and it’s rare that there’s anything left of last week’s offerings). If they had to spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars to comply with detailed labelling requirements for every small batch they brewed, they’d never stand a chance of making a profit. I understand the urge to ensure that people have a chance to avoid ingredients that might make them ill, but this is the sort of regulation that tilts very heavily toward the big companies that have regional or national markets. A thousand dollars per product isn’t even a drop in the bucket to them, while to a small local business, that might be more than their profit margin when you require it be done for everything they produce.

November 20, 2015

Here’s a very disturbing economic issue

At Coyote Blog, Warren Meyer shares his concerns about the constantly increasing regulatory burden of American business:

5-10 years ago, in my small business, I spent my free time, and most of our organization’s training time, on new business initiatives (e.g. growth into new businesses, new out-warding-facing technologies for customers, etc). Over the last five years, all of my time and the organization’s free bandwidth has been spent on regulatory compliance. Obamacare alone has sucked up endless hours and hassles — and continues to do so as we work through arcane reporting requirements. But changing Federal and state OSHA requirements, changing minimum wage and other labor regulations, and numerous changes to state and local legislation have also consumed an inordinate amount of our time. We spent over a year in trial and error just trying to work out how to comply with California meal break law, with each successive approach we took challenged in some court case, forcing us to start over. For next year, we are working to figure out how to comply with the 2015 Obama mandate that all of our salaried managers now have to punch a time clock and get paid hourly.

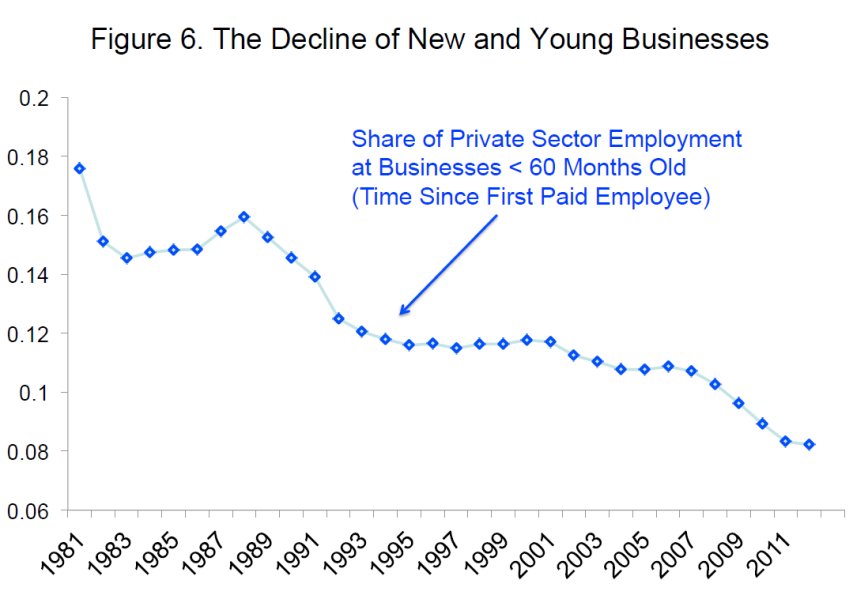

Greg Mankiw points to a nice talk on this topic by Steven Davis. For years I have been saying that one effect of all this regulation is to essentially increase the minimum viable size of any business, because of the fixed compliance costs. A corollary to this rising minimum size hypothesis is that the rate of new business formation is likely dropping, since more and more capital is needed just to overcome the compliance costs before one reaches this rising minimum viable size. The author has a nice chart on this point, which is actually pretty scary. This is probably the best single chart I have seen to illustrate the rise of the corporate state:

November 18, 2015

A maple-flavoured world’s first?

On the Mercatus Centre site, Laura Jones points out an unexpected Canadian first:

Canada recently became the first country in the world to legislate a cap on regulation. The Red Tape Reduction Act, which became law on April 23, 2015, requires the federal government to eliminate at least one regulation for every new one introduced. Remarkably, the legislation received near-unanimous support across the political spectrum: 245 votes in favor of the bill and 1 opposed. This policy development has not gone unnoticed outside Canada’s borders.

Canada’s federal government has captured headlines, but its approach was borrowed from the province of British Columbia (BC) where controlling red tape has been a priority for more than a decade. BC’s regulatory reform dates back to 2001 when a newly elected government put in place policies to make good on its ambitious election promise to reduce the regulatory burden by one-third in three years. The results have been impressive. The government has reduced regulatory requirements by 43 percent relative to when the initiative started. During this time period, the province went from being one of the poorest-performing economies in the country to being among the best. While there were other factors at play in the BC’s economic turnaround, members of the business community widely credit red tape reduction with playing a critical role.

The British Columbia model, while certainly not perfect, is among the most promising examples of regulatory reform in North America. It offers valuable lessons for US governments interested in tackling the important challenge of keeping regulations reasonable. The basics of the BC model are not complicated: political leadership, measurement, and a hard cap on regulatory activity.

This paper describes British Columbia’s reforms, evaluates their effectiveness, and offers practical “lessons learned” to governments interested in the elusive goal of regulatory reform capable of making a lasting difference. It also offers some important lessons for business groups and think tanks outside government that are pushing to reduce red tape. These groups can make all the difference in framing the issue in such a way that it can gain wide support from policymakers. A brief discussion of the challenges of accurately defining and quantifying regulation and red tape add context to understanding the BC model, and more broadly, some of the challenges associated with effective exercises in cutting red tape.

While I’m a huge fan of reducing the regulatory burden in theory, I can’t help but expect to be disappointed about the implementation in reality… (however, should the federal bureaucracy somehow manage to perform nearly as well as the BC experiment, it’ll be Justin Trudeau getting the credit for it, rather than Stephen Harper — but better that the country benefits as a whole rather than the former PM gets boasting rights.)

November 14, 2015

The US government has morphed from being part of “us” to being “them”

Charles Murray explains why so many Americans are feeling alienated from their own government:

I have been led to this position by what I believe to be a truth about where America stands: The federal government is no longer “us” but “them.” It is no longer an extension of the people through their elected representatives. It is no longer a republican bulwark against the arbitrary use of power. It has become an entity unto itself, separated from the American people and beyond the effective control of the political process. In this situation, the foundational principles of our nation come into play: The government does not command the blind allegiance of the citizenry. Government is instituted to protect our unalienable rights. The more destructive it becomes of those rights, the less it can call upon our allegiance.

I won’t try to lay out the whole case for concluding that our duty of allegiance has been radically diminished — that takes a few hundred pages. But let me summarize the ways in which the federal government has not simply become bigger and more intrusive since Bill Buckley founded National Review, but has also become “them,” and no longer an extension of “us.”

[…]

In 1937, Helvering v. Davis explicitly held that the federal government could spend money on the “general welfare,” establishing that the government’s powers were not limited to those enumerated in the Constitution. In 1938, Carolene Products did what the Ninth Amendment had been intended to prevent — it limited the rights of the American people to those that were explicitly mentioned in the Constitution and its amendments. Making matters worse, the Court also limited the circumstances under which it would protect even those explicitly named rights. In 1942, Wickard v. Filburn completed the reinterpretation of “commerce” so that the commerce clause became, in the words of federal judge Alex Kozinski, the “Hey, you can do anything you feel like” clause.

Momentous as these decisions were, they were arguably not as crucial to the evolution of the federal government from “us” to “them” as the decisions that led to the regulatory state. Until the 1930s, a body of jurisprudence known as the “nondelegation doctrine” had put strict limits on how much power Congress could delegate to the executive branch. The agencies of the executive branch obviously had to be given some latitude to interpret the text of legislation, but Congress was required to specify an “intelligible principle” whenever it passed a law that gave the executive branch a new task. In 1943, National Broadcasting Co. v. United States dispensed with that requirement, holding that it was okay for Congress to tell the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to write regulations for allocating radio licenses “as public convenience, interest, or necessity requires” — an undefined, and hence unintelligible, principle. And so we now live in a world in which Congress passes laws with grandiose goals, loosely defined, and delegates responsibility for interpreting those goals exclusively to regulatory agencies that have no accountability to the citizenry and only limited accountability to the president of the United States.

The de facto legislative power delegated to regulatory agencies is only one aspect of their illegitimacy. Citizens who have not been hit with an accusation of a violation may not realize how Orwellian the regulatory state has become. If you run afoul of an agency such as the FCC and want to defend yourself, you don’t go to a regular court. You go to an administrative court run by the agency. You don’t get a jury. The case is decided by an administrative judge who is an employee of the agency. You do not need to be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, but rather by the loosest of all legal standards, a preponderance of the evidence. The regulatory agency is also free of many of the rules that constrain police and prosecutors in the normal legal system. For example, regulatory agencies are not required to show probable cause for getting a search warrant. A regulatory agency can inspect a property or place of business under broad conditions that it has set for itself.

There’s much more, but it amounts to this: Regulatory agencies, or the regulatory divisions within cabinet agencies, operate as self-contained entities that create de facto laws that Congress would never have passed on an up-or-down vote. They then act as both police and judge in enforcing the laws they have created. It amounts to an extra-legal state within the state.

I have focused on the regulatory state because it now looms so large in daily life as to have provoked a reaction that crosses political divides: American government isn’t supposed to work this way.

October 28, 2015

Reducing the costs of regulation

Henry I. Miller discusses a worthwhile regulatory change that would increase the availability of medicines in the US marketplace without reducing public safety:

The FDA would be a good place to start. Bringing a new drug to market now requires 10-15 years, and costs have skyrocketed to an average of more than $2.5 billion (including both out-of-pocket and opportunity costs) – largely because FDA requirements have increased the length and number of clinical trials per marketing application, and their complexity.

The detrimental effects of FDA delays in approving certain new drugs already available in other industrialized countries are well-documented and deserve as much attention as drugs’ high costs. An example is the three-year delay in the approval of misoprostol, a drug for the treatment of gastric bleeding, which is estimated to have cost between 8,000 and 15,000 lives per year.

[…]

A practical workaround to overcome regulators’ risk-aversion and capriciousness would be “reciprocity” of approvals with certain foreign “A-list” governments, so that an approval in one country would be reciprocated automatically by the others. That would make more drugs available sooner in all of the participating countries, increasing competition and putting downward pressure on prices.

Such an innovation would also help to alleviate another critical problem: The United States is experiencing shortages of certain critical pharmaceuticals, many of which have been essential in medical practice for decades. The majority are generic injectable medications commonly used in hospitals, including analgesics, cancer drugs, anesthetics, antipsychotics for psychiatric emergencies, and electrolytes needed for patients on IV supplementation. Hospitals are scrambling to assure adequate supplies of drugs that are in short supply, or to find substitutes for them. Reciprocal approvals would make numerous alternatives available.

As referenced yesterday, the FDA regulations also create temporary monopoly situations where only one company has the permit from the regulator to produce this or that medicine, so there’s nothing standing in the way of massive price increases if there are no close substitutes to provide price competition.

October 27, 2015

Update on that $750 pill and the regulatory system that made it inevitable

Tim Worstall follows up on all-world scumbag Martin Shkreli and his enabled-by-the-regulator insane price increases for a decades-old drug:

We have an interesting and important economic lesson for public policy here: markets, they work. More accurately, we don’t have to worry about someone attempting to exploit their possession of a contestable monopoly. We only have to worry, possibly take action, if someone has an uncontestable monopoly. And given that there’s very few of them that we don’t create ourselves for other reasons, this means that monopoly is just one of those things we can keep a wary eye upon but not worry over excessively.

Our example comes from Martin Shkreli. The basic background is that this entrepreneur thinks he’s found a pretty cool business model. There’s a number of pharmaceuticals out there that are well out of patent but still have small and useful markets. FDA regulations (no, we’ll not go into the details of how or why this happens) mean that it’s not as easy as one might think to produce generic versions of these out of patent drugs. So, as a business plan, buy up the rights to the permit-ed (as in, with a permit, not just those allowed, as in permitted) generics and as a result of the difficulty someone else will have in getting into the same market, some pricing power is available. You can then raise the price and start to bank your considerable profits.

This caused outrage when Shkreli announced that this was exactly what he was doing:

Turing Pharmaceuticals, the company that last month raised the price of the decades-old drug Daraprim from $13.50 a pill to $750…

A 5,000% price rise certainly indicates that Turing thinks it has pricing power and thus that it has considerable monopoly power.

[…]

Markets, they work. As Mr. Shkreli is just finding out:

Turing Pharmaceuticals, the company that last month raised the price of the decades-old drug Daraprim from $13.50 a pill to $750, now has a competitor.

Imprimis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a specialty pharmaceutical company based in San Diego, announced today that it has made an alternative to Daraprim that costs about a buck a pill — or $99 for a 100-pill supply.

This is not the same drug: it’s a slight variation, a close substitute. But it’s close enough that Turing isn’t going to be making much money from what it thought was monopoly pricing power. Because it was a contestable monopoly, not an absolute one.

October 22, 2015

QotD: The historical triumph of public health

… the great public health achievements between roughly 1850 and 1960. Doctors and public health experts were given extraordinarily broad powers by the government, and they used them to eliminate the scourges that had made cities into pestholes from time immemorial. They built gleaming sewers and water treatment plants to wipe out virulent water-borne pathogens that used to regularly claim thousands of lives. Contact-tracing and quarantine of airborne and sexually transmitted diseases turned former plagues like smallpox and syphilis into tragic but sporadic outbreaks. Changes in building codes helped beat back mass killers like tuberculosis. Poison control cut down on both accidental and deliberate deaths. The Pure Food and Drug Act, and similar ordinances in other countries, reduced foodborne illness, and also, the casual acquisition of opiate or cocaine addictions through patent medicines. Malarial swamps were drained. Environmental toxins were identified and banned. Then they went and invented antibiotics and vaccines and vaccination laws, and suddenly surgery was as safe as a long-haul flight, TB was curable, and childhood illnesses that used to kill hundreds of people every year were a quaint footnote in your 10th-grade history textbook.

Having seen public experts work these miracles through the heavy hand of the state, people understandably concluded we could use miracles in other areas. They had a metaphor, so to speak. The metaphor wasn’t very good, as is often the case, but it took a while to find out that you couldn’t solve a problem in your steel supply chain with the same system that was so good at tracing cholera outbreaks to tainted pumps.

[…]

This is an overreaction to a terrible failure, for two reasons. First, big bureaucracies fail all the time, especially in the face of novel threats. A large institution is like a battleship: hard to sink, but also hard to turn. Public health experts of earlier eras made grave mistakes, like dumping London’s untreated sewage into the Thames; public health experts of the future will too. The more important question is whether they correct themselves, as it seems to me the CDC is now doing.

The second is that this is not your grandfather’s public health system. Public health experts were, in a way, too successful; they beat back our infectious disease load to the point where most of us have never had anything more serious than Human papillomavirus or a bad case of the flu. This left them without that much to do. So they reinvented themselves as the overseers of everything that might make us unhealthy, from French Fries to work stress.

As with the steel mills, these problems are not necessarily amenable to the organizational tools used to tackle tuberculosis. The more the public and private health system are focused on these problems, the less optimized they will be for fighting the war against infectious disease. It is less surprising to find that they didn’t know how to respond to a novel infectious disease than it would have been to discover that they botched a new campaign against texting and driving.

Megan McArdle, “Will Ebola Be Good for the CDC?”, Bloomberg View, 2014-10-20.

October 9, 2015

October 8, 2015

“[P]harmaceutical companies … make out like bandits from the existence of the patent system”

The current US patent system is set up to create and maintain — for a limited time — monopolies that can be exploited by pharmaceutical companies:

The Wall Street Journal has a puzzling piece complaining about how the pharmaceutical companies seem to make out like bandits from the existence of the patent system. What puzzles is that the entire point and purpose of the patent system, in an economic sense, is so that inventors of things can make out like bandits. The background problem is that of public goods, something I’ll explain in a moment. That problem leads us to thinking that a pure free market in things which are public goods isn’t going to work as well as something a little different. So, we design something a little different. And the point and purpose of our design is so that people who innovate can make vast mountains of cash out of having done so.

It’s then more than a bit odd to point out that our system enables people who innovate to make vast mountains of cash.

[…]

Which brings us to the subtlety of those pricing decisions. With drugs, pharmaceuticals, close enough the cost of manufacturing a dose is zero. All of the costs go in the original research, the clinical testing (the lion’s share) and getting it through the FDA. Profit is therefore determined, since marginal production costs are zero (they’re not, accurately, but close enough for this comparison), by gross revenue. And we want to maximise the incentive for people to innovate, that’s the very reason we’ve got this patent system in the first place, and thus we would rather like the pharma companies to be maximising revenue.

And thus, from this economic point of view, we should be quite happy with people raising their prices. Demand does fall as they do so, yes, but as long as gross revenue increases, the price rises more than compensating for the fall in unit demand, then we should be happy with the way the system is working. Gross revenue is being maximised, profits are being maximised, incentives to innovate are being maximised. That’s what we want our system to do after all.

Far from being worried about this price gouging we should be welcoming it. Because, obviously, someone making bajillions out of having innovated a drug to cure a disease increases the incentives for many other people to go and invest bajillions of their own to cure other diseases. Far from complaining about it we should be celebrating the system working.

October 1, 2015

QotD: The “epidemic” of sexual assault on campus

Wildly overblown claims about an epidemic of sexual assaults on American campuses are obscuring the true danger to young women, too often distracted by cellphones or iPods in public places: the ancient sex crime of abduction and murder. Despite hysterical propaganda about our “rape culture,” the majority of campus incidents being carelessly described as sexual assault are not felonious rape (involving force or drugs) but oafish hookup melodramas, arising from mixed signals and imprudence on both sides.

Colleges should stick to academics and stop their infantilizing supervision of students’ dating lives, an authoritarian intrusion that borders on violation of civil liberties. Real crimes should be reported to the police, not to haphazard and ill-trained campus grievance committees.

Too many young middle class women, raised far from the urban streets, seem to expect adult life to be an extension of their comfortable, overprotected homes. But the world remains a wilderness. The price of women’s modern freedoms is personal responsibility for vigilance and self-defense.

Camille Paglia, “The Modern Campus Cannot Comprehend Evil”, Time, 2014-09-29.

September 25, 2015

Reducing income inequality

Tim Worstall in Forbes:

There’s a fascinating and very long essay over in National Affairs about how we might cut income inequality. And, contrary to what any number of Democratic candidates for office will tell you, the answer isn’t to impose ever more regulation upon the economy. Rather, it’s to strip away some of the regulation that allows certain favoured income groups to make excessive incomes. Excessive here defined as greater than the economic value they add to the lives of the rest of us, something they achieve by carving out economic rents for themselves. I would, myself, go rather further than the writer, Steven Teves, and start using Mancur Olson’s analysis, that this is what democratic (note, democratic, not Democratic) politics always devolves down into, a carving up of the public sphere to favour certain interest groups. But even this milder version gives us more than just hints about what we should be doing:

At the same time, however, we have seen an explosion in regulations that shower benefits on the very top of the income distribution. Economists call these “rents,” which we can define for simplicity’s sake as legal barriers to entry or other market distortions created by the state that create excess profits for market incumbents.

Let us take one very simple example of such rents. The earnings of those who possess taxi medallions in cities where there’s an insufficient number issued. Until very recently one such medallion, allowing one single cab to operate on the streets of NYC 24/7, had a capital value of $1 million. That led to a rent, a pure economic rent, of $40,000 a year to allow one cab river to use that medallion for 12 hours of the day. and, obviously, another $40,000 to allow another to use it for another 12 hours a day.

That is purely a rent: and one created by New York City not issuing enough medallions to cover the demand for cab services. Uber has of course exploded into this market and the success of that company, along with its many competitors, shows how pervasive the creation of such rents by limiting taxi numbers has been in cities around the world. That is an obvious and very clear creation of a rent purely through bureaucratic action.

[…]

Deregulating the economy will remove many of those rents. This will reduce income inequality. So, why aren’t those who rail against income inequality shouting for deregulation? Good question and the only proper answers become increasingly cynical. Unions exist for the purpose of creating rents for their members. So, given the union participation in the Democratic Party we’re not going to see calls for deregulation from that side. And different groups, those car dealers perhaps, the doctors, have their hooks into the Republican Party too.

My own answer is that it needs to be done in the same manner that Reagan treated the tax code. Not that I’m particularly stating that Reagan’s tax changes were quite as wondrous as some now think they were, only that it all had to be approached on a Big Bang basis. Everything had to be on the table at the same time so that while there were indeed those who would defend their little corner the over riding interest of all was that all such little corners got eradicated. With this rent creation, given that so much of it is at State level, that won’t really work. Except for one idea that I’ve floated before.

September 24, 2015

Ontario takes baby steps toward liberalizing the beer market

At the Toronto Beer Blog, a less-than-enthused look at the latest changes to minimally change the just-barely-beyond-prohibition-era rules for selling beer in Ontario:

This has been a noisy day in the wonderful world of beer sales in Ontario. The Liberal government released the details of the new 195 page master agreement between The Beer Store, the Province (LCBO), and the new kids on the block, grocery stores.

Much of the information is what we heard when they announced it with the budget. Some more details have come out. If you read my thoughts in April, you will remember I was not happy. I’m still not.

The good from today’s news is there are some clear definitions of what constitutes a grocery store (10 000 sq/feet dedicated to groceries, not primarily identified as a pharmacy); that the 20% craft shelf space is for both grocery stores and The Beer Store, and that there cannot be a fee to get listed (though we all know how effectively the province enforces pay-to-play in bars around the province); and that they have some novel system to divide sales licenses between both huge chains and independent grocers.

The old news about shared shipping for smaller breweries and no volume limit for a second on-site retail location are accurate, and very good news.

But here’s the thing: This is just more Ontario political craziness.

This is to “level the field”, apparently for small brewers, who nobody would suggest get a fair shake in the current system.

But what could have been an actual leveling of the playing field, turned out to be more insanity and government control and meddling. And remember, I’m saying that as a sworn lefty nutjob, who generally thinks having controls and regulations is a good thing.

Remember, these are not the ravings of a far-right-wing free-enterprise-maniac … these are the regrets of a self-described “sworn lefty nutjob”:

A level playing field would be one where anybody could apply for a license to sell beer, and do it. A brewery can pick and choose who they sell to, as a retailer can choose who they do business with. Nobody would need to guarantee a percentage of shelf space, because the market would control what products were successful and got shelf space.

This isn’t a level playing field, it’s just a bunch of new rules to try to counter how horrible we’ve allowed our playing field to get. Yes, it will be more convenient for people who shop at one of the 450 stores that have a license. But the agreement still favours The Beer Store heavily (for instance, grocers are limited in the volume they can sell. They can exceed the limit, but then have to pay a fine to the LCBO who distribute it to, you guessed it, the breweries who own The Beer Store to offset their lost sales. Seriously).

September 23, 2015

In debt to the bank? Underwater on your mortgage? You might want to check the document carefully…

At The Intercept, David Dayen says that there are a lot of sketchy documents that banks are hoping will stand up in court, but they might well be wrong:

A Seattle housing activist on Wednesday uploaded an explosive land-record audit that the local City Council had been sitting on, revealing its far-reaching conclusion: that all assignments of mortgages the auditors studied are void.

That makes any foreclosures in the city based on these documents illegal and unenforceable, and makes the King County recording offices where the documents are located a massive crime scene.

The problems stem from the Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (MERS), an entity banks created so they could transfer mortgages privately, saving them billions of dollars in transfer fees to public recording offices. In Washington state, MERS’ practices were found illegal by the State Supreme Court in 2012. But MERS continued those practices with only cosmetic changes, the audit found.

That finding has national implications. Every state has its own mortgage laws, and some of the audit’s conclusions may not necessarily apply elsewhere. But it shows how MERS reacted to being caught defrauding the public by trying to sneak through foreclosures anyway. Combined with evidence in other parts of the country, like the failure to register out-of-state business trusts in Montana, it suggests that the mortgage industry has been inattentive to and dismissive of state foreclosure laws.