Secret Base

Published 15 Aug 2023The Minnesota Vikings of the 1970s were among the greatest football teams ever assembled. Entering 1974, Bud Grant’s teams had reached two Super Bowls, but lost them both. The good times don’t last forever. It’s time to cash in.

Written and directed by Jon Bois

Written and produced by Alex Rubenstein

Rights specialist Lindley Sico

Secret Base executive producers Will Buikema and Jon BoisKnown goofs:

• At about the 42-minute mark, Jon says Fran Tarkenton held a 45-8-1 record as starter between 1973 and 1976. His record across these years was actually 43-10-1.

(more…)

August 28, 2023

The Last Chance | Dorktown

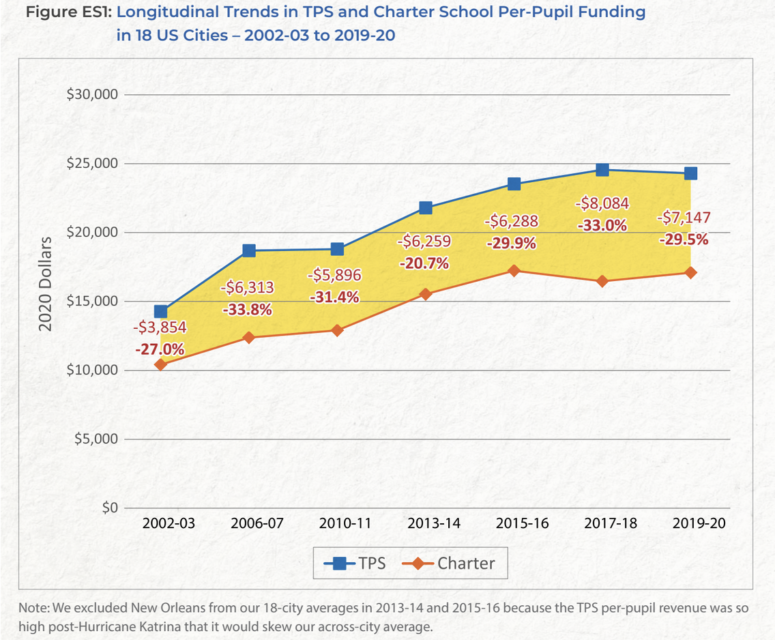

Charter school students do better academically, yet are funded at a lower level than other students

Jack Elbaum on recent studies that show charter schools in the United States have higher academic success rates than ordinary state-funded schools, despite a significantly lower funding rate:

If you thought charter schools received anywhere near the same amount of funding as traditional public schools, then think again.

A new, massive study from the University of Arkansas finds that “On average, charter schools across 18 cities in 16 states (…) receive about 30 percent or $7,147 (2020 dollars) less funding per pupil than traditional public schools.” Over the past two decades, this funding disparity has remained relatively stable.

The gaps are, predictably, more severe in some places than others. The study notes that “Atlanta has the largest percentage-based charter funding disparity (about 53 percent), while Camden has the largest disparity in dollars ($19,711). Houston has the smallest disparity in terms of percent (three percent) and dollars ($417).”

Importantly, the regression analysis run by the authors did not suggest differences in the proportion of students in poverty or English Language Learners are the reason for the disparity. However, it did find that after taking into account differences in the number of special needs students, the disparity dropped considerably — although it remained significant ($1,707).

[…]

Based on these data alone, it would not be unreasonable for one to expect that these charter schools had worse educational outcomes than their traditional public school counterparts.

The only issue is that this is not the case.

A recent study from Stanford University, for example, found that charter school students gain 16 days’ worth of reading and six days of math per year relative to those in traditional public schools. These benefits were particularly pronounced among minority students who were also in poverty. Education Week reported that “Black charter students in poverty gained 37 days of learning in reading and 36 days in math over their counterparts in traditional public schools, and Hispanic students in poverty gained 36 days of reading and 30 days of math over their traditional public school peers.”

Economist Thomas Sowell’s 2020 book Charter Schools and Their Enemies also offers compelling data suggesting the efficacy of charter schools. He studied a set of charters and traditional public schools in New York City that served essentially identical populations. In many cases in the study, a charter school and traditional public school would even occupy the same building.

Why Britain Advanced Before Other European Nations | Thomas Sowell

Thomas SowellTV

Published 17 Dec 2021

(more…)

August 27, 2023

Climategate 2023: Electric Boogaloo? The first time as tragedy, the second as farce?

At Climate Sceptic, Chris Morrison outlines the circumstances around the retraction of a journal article critical of the “climate consensus”:

Shocking details of corruption and suppression in the world of peer-reviewed climate science have come to light with a recent leak of emails. They show how a determined group of activist scientists and journalists combined to secure the retraction of a paper that said a climate emergency was not supported by the available data. Science writer and economist Dr. Roger Pielke Jr. has published the startling emails and concludes: “Shenanigans continue in climate science, with influential scientists teaming up with journalists to corrupt peer review”.

The offending paper was published in January 2022 in a Springer Nature journal and at first attracted little attention. But on September 14th the Daily Sceptic covered its main conclusions and as a result it went viral on social media with around 9,000 Twitter retweets. The story was then covered by both the Australian and Sky News Australia. The Guardian activist Graham Readfearn, along with state-owned Agence France-Presse (AFP), then launched counterattacks. AFP “Herald of the Anthropocene” Marlowe Hood said the data were “grossly manipulated” and “fundamentally flawed”.

After nearly a year of lobbying, Springer Nature has retracted the popular article. In the light of concerns, the Editor-in-Chief is said to no longer have confidence in the results and conclusion reported in the paper. The authors were invited to submit an addendum but this was “not considered suitable for publication”. The leaked emails show that the addendum was sent for review to four people, and only one objected to publication.

What is shocking about this censorship is that the paper was produced by four distinguished scientists, including three professors of physics, and was heavily based on data used by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The lead author was Professor Gianluca Alimonti of Milan University and senior researcher of Italy’s National Institute of Nuclear Physics. Their paper reviewed the available data, but refused to be drawn into the usual mainstream narrative that catastrophises cherry-picked weather trends. During the course of their work, the scientists found that rainfall intensity and frequency was stationary in many parts of the world, and the same was true of U.S. tornadoes. Other meteorological categories including natural disasters, floods, droughts and ecosystem productivity showed no “clear positive trend of extreme events”. In addition, the scientists noted considerable growth of global plant biomass in recent decades caused by higher levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

In fact this scandal has started to attract comparison with the Climategate leaks of 2009 that also displayed considerable contempt for the peer-review process. One of the co-compilers of the Met Office’s HadCRUT global temperature database Dr. Phil Jones emailed Michael Mann, author of the infamous temperature “hockey stick”, stating: “I can’t see either of these papers being in the next IPCC report. Kevin and I will keep them out somehow – even if we have to redefine what the peer-reviewed literature is!”

The Liberation of Paris – WW2 – Week 261 – August 26, 1944

World War Two

Published 26 Aug 2023Paris is liberated by the Allies, a symbolic act that causes the world to rejoice. Something far more important to the course of the war, though, happens this week in Romania. The Allies continue to advance in the south of France and begin a new offensive in Italy, though the Pacific War has quietened down once again.

(more…)

When the techno-utopians proclaimed the end of the book

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte harks back to a time when brash young tech evangelists were lining up to bury the ancient codex because everything would be online, accessible, indexed, and (presumably) free to access. That … didn’t happen the way they forsaw:

By the time I picked up Is This a Book?, a slim new volume from Angus Phillips and Miha Kova?, I’d forgotten the giddy digital evangelism of the mid-Aughts.

In 2006, for instance, a New York Times piece by Kevin Kelly, the self-styled “senior maverick” at Wired, proclaimed the end of the book.

It was already happening, Kelly wrote. Corporations and libraries around the world were scanning millions of books. Some operations were using robotics that could digitize 1,000 pages an hour, others assembly lines of poorly paid Chinese labourers. When they finished their work, all the books from all the libraries and archives in the world would be compressed onto a 50 petabyte hard disk which, said Kelly, would be as big as a house. But within a few years, it would fit in your iPod (the iPhone was still a year away; the iPad three years).

“When that happens,” wrote Kelly, “the library of all libraries will ride in your purse or wallet — if it doesn’t plug directly into your brain with thin white cords.”

But that wasn’t what really excited Kelly. “The chief revolution birthed by scanning books”, he ventured, would be the creation of a universal library in which all books would be merged into “one very, very, very large single text”, “the world’s only book”, “the universal library.”

The One Big Text.

In the One Big Text, every word from every book ever written would be “cross-linked, clustered, cited, extracted, indexed, analyzed, annotated, remixed, reassembled and woven deeper into the culture than ever before”.

“Once text is digital”, Kelly continued, “books seep out of their bindings and weave themselves together. The collective intelligence of a library allows us to see things we can’t see in a single, isolated book.”

Readers, liberated from their single isolated books, would sit in front of their virtual fireplaces following threads in the One Big Text, pulling out snippets to be remixed and reordered and stored, ultimately, on virtual bookshelves.

The universal book would be a great step forward, insisted Kelly, because it would bring to bear not only the books available in bookstores today but all the forgotten books of the past, no matter how esoteric. It would deepen our knowledge, our grasp of history, and cultivate a new sense of authority because the One Big Text would indisputably be the sum total of all we know as a species. “The white spaces of our collective ignorance are highlighted, while the golden peaks of our knowledge are drawn with completeness. This degree of authority is only rarely achieved in scholarship today, but it will become routine.”

And it was going to happen in a blink, wrote Kelly, if the copyright clowns would get out of the way and let the future unfold. He recognized that his vision would face opposition from authors and publishers and other friends of the book. He saw the clash as East Coast (literary) v. West Coast (tech), and mistook it for a dispute over business models. To his mind, authors and publishers were eager to protect their livelihoods, which depended on selling one copyright-protected physical book at a time, and too self-interested to realize that digital technology had rendered their business models obsolete. Silicon Valley, he said, had made copyright a dead letter. Knowledge would be free and plentiful—nothing was going to stop its indiscriminate distribution. Any efforts to do so would be “rejected by consumers and ignored by pirates”. Books, music, video — all of it would be free.

Kelly wasn’t altogether wrong. He’d just taken a narrow view of the book. He was seeing it as a container of information, an individual reference work packed with data, facts, and useful knowledge that needed to be agglomerated in his grander project. That has largely happened with books designed simply to convey information — manuals, guides, dissertations, and actual reference books. You can’t buy a good printed encyclopedia today and most scientific papers are now in databases rather than between covers.

What Kelly missed was that most people see the book as more than a container of information. They read for many reasons besides the accumulation of knowledge. They read for style and story. They read to feel, to connect, to stimulate their imaginations, to escape. They appreciate the isolated book as an immersive journey in the company of a compelling human voice.

6 Strange Facts About the Cold War

Decades

Published 27 Jul 2022Welcome to our history channel, run by those with a real passion for history & that’s about it. In today’s video, we will be exploring 6 odd Cold War facts.

(more…)

QotD: Getting food to market in pre-modern societies

The most basic kind of transport is often small-scale overland transport, either to and from the nearest city, or in small (compared to what we’ll discuss in a moment) caravans moving up and down a region […]. The Talmud, for instance, seems to suggest that much of the overland grain trade in Palestine under the Romans was performed with itinerant donkey-drivers in small caravans – and I do mean small. Egyptian tax evidence suggests that most caravans were small; Erdkamp notes that 90% of donkey caravans and 75% of camel caravans consisted of three or less animals. These sorts of small caravans don’t usually specialize in any particular good but instead function like land-based cabotage traders, buying whatever seems likely to turn a profit at each stop and stopping in each town and market along the way. Some farmers might even do this during the off season; in Spain, peasants often worked as muleteers during the slow farming season, moving rents and taxes into town or to points of export for their wealthy landlords and neighbors.

Truly long-distance bulk grain transport overland wasn’t viable for reasons we’ve actually already discussed. There is simply nothing available in the pre-modern period to carry the grain overland that doesn’t also eat it. While moving grain short distances (especially to simply fill capacity while the main profit is in other, lower-bulk, higher value goods) can be efficient enough, at long distance, all of the grain ends up eaten by the animals or people moving it.

The seaborne version of this sort of itinerant, short-distance trade is called cabotage. Now today cabotage has a particular, technical legal meaning, but when we use this word in the past, it refers not to the legal status of a ship but a style of shipping using small boats to move mixed cargo up and down the coast. In essence, cabotage works much the same as the small caravans – the merchant buys in each port whatever looks likely to turn a profit and sells whatever [is] in demand. By keeping a mixed cargo of many different sorts of things, he protects against risk – he’s always likely to be able to sell something in his boat for a profit. Such traders generally work on very short distances, often connecting smaller ports which simply cannot accommodate larger, deeper-draft long-distance traders. Such cabotage trading was the background “hum” of commerce on many pre-modern coastlines and might serve to move grain up or down the coast, although not very much of it. Remember that grain is a bulk commodity, and cabotage traders, by definition, are moving small volumes.

But when it comes to moving large volumes, the sea changes everything. The fundamental problem with transporting food on land is that the energy to transport the food must come from food, either processed into muscle power by porters or animals. But at sea, that energy can come from the wind. So while the crew of a ship eats the food, the ship can be scaled up without scaling up the food requirements of the crew or the crew itself. At the same time, sea-transit is much faster than land transit and that speed is obtained from the wind without further inputs of food. It is hard to overstate how tremendous a change in context this is. Using the figures from the Price Edict of Diocletian, we tend to estimate that river transport was five times cheaper than land transport, and sea-transport was twenty times cheaper than land transport. So while the transport of bulk goods like grain on land was limited to fairly small amounts moving over short distances – say from the farm to the nearest town or port – grain could be moved long distances en masse by sea.

Now the scale and character of long-distance transport is heavily impacted by the political realities of the local waterways. If the seas are politically divided, or full of pirates, it is going to be hard to operate big, slow vulnerable grain-freighters and still make a profit after some of them get seized, pirated or sunk. But when we have periods of political unity and relatively safe seas, we see that this sort of transport can reach quite impressive scale. For instance the port regulations of late Hellenistic and Roman Thasos – itself a decent sized, but by no means massive port – divided its harbor into two areas, one for ships carrying 80-130 tons of cargo and one for ships 130+ tons (those regulations are SEG XVII 417). A brief bit of math indicates that the distribution of free grain in the city of Rome – likely less than a third of the total grain demands of the city – required the import, by sea of some 630 tons of grain per day through the sailing season. The scale of grain shipment in the back half of the Middle Ages (post-1000 or so) was also on a vast scale, with trade-oriented Italian cities exploding in population as they imported grain (Genoa being particularly well known for this, but by no means alone in it); with that came the reemergence of truly large grain-freighters.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part IV: Markets, Merchants and the Tax Man”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-08-21.

August 26, 2023

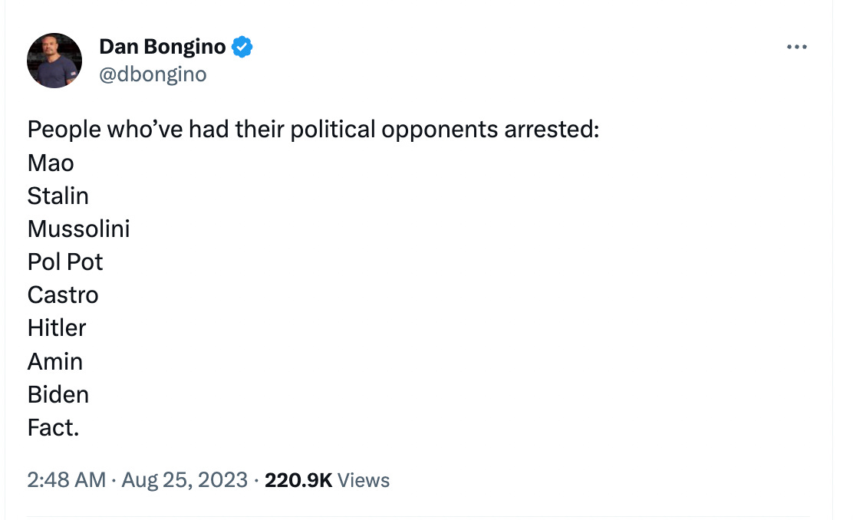

The United Banana Republics of America and their efforts to “get” Trump

Chris Bray points out an interesting historical precedent for the US government’s determination to pin something on former President Donald Trump:

There’s a whole lot of this sentiment on social media this morning, and I agree with it entirely:

But also read this. It’s important, and it’ll take you three minutes. Click on that link and read. You’ll see the point with every paragraph.

There are American precedents for the shameful acts of disgusting political lawfare being directed against Donald Trump (and his lawyers and political staff), and the most obvious and extremely telling precedent is the behaviour of Federalists during the Adams administration. The Sedition Act of 1798 made criticism of the federal government a crime, on a comparable construction of the idea of “disinformation” that’s now used as a repressive tool: the law forbade “any false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the government, subjective terms that in practice opened the prison doors to mere disagreement and ordinary political criticism. Federalists arrested and prosecuted newspaper editors and a congressman. Representative Matthew Lyon was imprisoned for criticizing the Adams administration.

But the effects of the Sedition Act are extremely important. Here’s a description from archives.gov — from a site run by the federal government:

The laws were directed against Democratic-Republicans, the party typically favoured by new citizens. The only journalists prosecuted under the Sedition Act were editors of Democratic-Republican newspapers.

Sedition Act trials, along with the Senate’s use of its contempt powers to suppress dissent, set off a firestorm of criticism against the Federalists and contributed to their defeat in the election of 1800, after which the acts were repealed or allowed to expire.

The criminalization of dissent by Federalists destroyed the Federalists. The party went into a hard decline; John Adams became the only Federalist president in our history (because Washington, sentimentally a federalist, declined to identify as a Federalist), though the party continued to be regionally important in New England until it finally destroyed itself at the Hartford Convention. The event that historians call the Revolution of 1800, the election of the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson to the presidency, was in significant part a result of American disgust over the political repression of dissent1. See this point clearly:

Federalists jailed their political opposition, so America loathed the Federalists and turned against them.

1. See also the High Federalist response to the Fries Rebellion, which treated a careful act of resistance as a dangerous insurrection. If you’ve never read about this one, I strongly recommend this book.

“Email jobs”, as defined by Freddie deBoer

Freddie deBoer offers some notes on what he calls “a book I’ll probably never write”:

When I talk to people about college-educated workers, even informed people, there’s a constant tendency to immediately think of doctors, lawyers, engineers, data scientists … Reflexively, people seem to think of educated labor in terms of college graduates who a) tend to go on to some sort of graduate study, b) work in fields that directly utilize domain-specific knowledge from their majors or graduate education, and c) are generally high-income relative to the economy writ large. These professions, combined, are a healthy slice of our labor force, and there’s nothing wrong with paying an appropriate amount of attention to them. But I think the amount of attention they’re given in the educational and economic discourse is in fact disproportionate. And I also think that there’s a kind of profession that is intuitively very understandable but which (despite considerable effort on my part) remains very difficult to classify and thus to quantify. Though it has many names, I think my preferred term is “email job”.

[…]

To me, prototypical email jobs

- Depend, naturally, on email and other digital communicative tools like video conferencing, online calendars, and networked workspaces for the large majority of their actual productive capability

- Are staffed almost entirely by people with college degrees, but while they do take advantage of time management and organizational skills that can be developed in college, almost never call on domain-specific knowledge related to a particular major

- Dedicate a considerable amount of time not to the named productive goals of the job themselves but to meta-tasks that are meant to facilitate those goals (scheduling, coordinating, assigning responsibility, “touching base”, enhancing productivity, ensuring compliance with various HR-mediated job requirements and odd whims of the boss)

- Have no immediate observable impact on the material world; an email job might involve coordinating or supporting or assessing a project that will eventually move some atoms around, but the email job itself results only in the manipulation of bits

- Cannot be considered creative in any meaningful sense — they do not entail the production of new stories, scripts, code, images, video, blueprints, patents, research papers, etc — but may involve the creation of materials that are subsidiary to larger administrative goals, such as PowerPoint presentations, reports, postmortems, or white papers

- May or may not be partially or fully remote but could likely be performed fully remotely/on a “work from home” basis without issue

- Can involve supervising lower-level workers, even teams, but these positions are not themselves fundamentally supervisory and the holder of an email job is rarely the only “report” for anyone; these positions, in other words, are not executive or executive-track, though some may escape the email job track and gain entry to the executive track

- Tend to top out at middle management, and often have a salary range (with a great deal of wiggle) between $50,000 and $200,000/year.

Doctors do not have email jobs because the human bodies they treat exist in the world of atoms, not the world of bits, and their work involves domain-specific knowledge. There are some lawyers who are effectively in email jobs, as their law credentials are used for hiring purposes but their actual task is handling particular kinds of paperwork that a non-lawyer could complete, but most lawyers are not in email jobs as their work involves various functions at courthouses and otherwise away from the computer, and anyway their work too involves domain-specific knowledge. Most accountants and actuaries are not in email jobs as their jobs require domain-specific knowledge that they acquired in formal education. Architects create new things that will someday exist in the world of atoms and utilize domain-specific knowledge they learned in college. Programmers take advantage of skills gained in college to create new things that exist for their own purpose, rather than to satisfy other administrative functions. Professors don’t have email jobs, even those who work at online colleges, as working with students takes place in the world of atoms and they are constantly accessing domain-specific knowledge they learned in formal education. Screenwriters create something new; engineers move atoms and usually get graduate degrees; CEOs don’t have email jobs because they’re on the executive track and enjoy the ability to delegate most of the email work to subordinates. I could go on.

So who does have an email job? Take someone who works in accreditation at a college in a large public university system. He or she didn’t get a major in accreditation (there is no such major) and is unlikely to have majored in education, and even if they did they would have learned about pedagogy and “theory” and assessment rather than anything having to do with their daily work lives. Essentially everything they do for work takes place within the confines of their laptop screen, and the exception is various in-person meetings that accomplish nothing beyond delegating various tasks, defining roles, critiquing past performance, and otherwise reflecting on how to do a better job of supporting the tasks that other people do. A person in this job might have a secretary or lower-level administrative functionary that reports to them, but they are not on a track that makes advancement likely — becoming a VP somewhere will likely require many years of service and going on the job market to get a job at another school. A person in this position will never interact with students in any real capacity, demonstrating the psychic distance between email jobs and the actual function of their institutions. Though they have a clear and defined set of responsibilities written into their job description, their overall impact on the day-to-day functioning of their college is nebulous, and far more time is spent on administrivia than their “real” duties. They live between the 50th and 75th percentile for individual income in their state.

The Cloward-Piven strategy in action

David Solway outlines the “playbook” apparently being followed in the ongoing dismantling of western civilization:

The malignant playbook of the contemporary left is generally considered to be Saul Alinsky’s 1989 Rules for Radicals, and there is certainly much truth to the story of the book’s destructive influence. But the source text for social and political upheaval is Richard Cloward and Francis Fox Piven’s far more detailed and authoritative 1997 manual, The Breaking of the American Social Compact.

The Cloward-Piven strategy seeks to hasten the fall of the free market and the republican structure of government by overloading the administrative apparatus with an avalanche of impossible demands, thus pushing society into crisis mode and eventual economic collapse. Choking the welfare rolls, for example, would serve to generate a political and financial meltdown, break the budget, jam the bureaucratic gears, and bring the system crashing down. The fear, turmoil, and violence accompanying such a debacle would provide the perfect conditions for fostering radical change.

We see the strategy in action today, forging a situation that was unnecessary from the start via a series of tactical steps, among which: the campaign against productive farming; the so-called 15-minute city herding people into condo-congested urban centers where they are readily supervised and mastered; open borders allowing for a refugee tsunami to alter the character of the nation; a censoring and disinformative media rendered corrupt to the core; the mandating of useless masks or plausibly toxic vaccines; and the implementation of a digital currency in which citizens’ spending can be monitored, restricted, or even frozen. Such phenomena have no basis in even the remotest necessity but are essential in order to prepare the ground for an imminent totalitarian state.

This is the rationale for the so-called COVID pandemic and the bugbear of “Climate Change”. A bad flu season affecting mainly the elderly with comorbidities is not a viral pandemic, as Dr. Vernon Coleman ironically shows. The climate is always changing as a matter of course — the term “climate change” is a gross oxymoron; the thesis of anthropogenic forcing obscures the fact that carbon is material for life and nitrogen for farming. COVID and Climate are tactical phantoms that have nothing to do with reality and everything to do with social control. The Clowardly rePivening put in place by the Democrat Party has only one aim: to create a crisis out of thin air and then seek to defuse it by creating a real crisis that advantages only the Party. It is the diabolical form of creation ex nihilo.

Thus, a ginned-up pandemic is a perfect excuse for mail-in ballots and ballot harvesting, especially if the voter rolls have been flooded with uncountable and counterfeit names and the voting stations have been commandeered. There is no immigration chaos unless a chain system is entrenched and the border is left wide open. There is no such thing as “white supremacy” unless it is apodictically proclaimed and false-flag operations are carried out. There is no need for costly, largely ineffective, and harmful renewable energy installations unless drilling has been rendered illegal and the oil pipelines have been shut down to avoid a bogus climate catastrophe. The bible of the Democrat left begins: Let there be a crisis. And there was a crisis.

H/T to Blazing Cat Fur for the link.

OSS “Bigot” 1911 dart-firing pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 2 Apr 2012The “Bigot” was a modification of an M1911 .45 caliber pistol developed by the Office of Strategic Services during WW2. The OSS was a clandestine operations service, the predecessor of the CIA. The Bigot was intended as a way for commandos to quietly eliminate sentries — although we are not sure what advantage it might have had over a silenced pistol. Questionable utility doesn’t prevent it from being a pretty interesting piece of equipment, though, and we had the opportunity to take a look at one up close recently.

QotD: The psychological value of “making”

The Domestic Revolution is a fascinating tour of the ways relatively minor changes snowball, changing the way people interact with the material world and with one another, but it’s also a tremendous pleasure for its lucid, practical explanations of how these things actually work. Goodman is deeply familiar with her tools and materials in a way that’s quite unusual today. Of course anyone who really makes things will have this familiarity — ask a software engineer about programming languages or his favourite text editor — but in most walks of life actually making things has become increasingly optional. Of the objects I interact with on a daily basis, the only ones I can really be said to have made (my kids don’t count) are the things I cook and the chairs I refinished and upholstered.1 Beyond that there’s the garden I planted with seeds and perennials I bought at a nursery, the furniture I assembled out of pieces some nice Swedish man machined for me, and the various bits of plumbing I’ve swapped out, but none of that is really “making” so much as it is “assembling things other people have made”. It’s mostly the productive equivalent of last mile delivery — nothing to sneeze at, but a far cry from the sort of deep involvement with the material world that was common only a few centuries ago.

This makes perfect sense, of course: I don’t have a deep and intimate knowledge of these things because I don’t need one. Still, though, it’s important to have a certain very basic familiarity with how the things around you work — enough, say, to know what to Google when something breaks and how to put the results into practice, or to turn fifteen feet of arching blackberry cane into an actual bush — because it gives you power over your world. The particular powers don’t really matter (it’s easy enough to pay someone else to fix your plumbing or grow your berries); the key is the patterns of thought they engender. There are, for example, apparently some enormous number of people who don’t change the batteries in their beeping smoke detectors. I have no idea whether it’s drug-induced apathy, ignorance of how things work (in the same way that drilling a hole in your wall to hang something seems scary if you don’t know that your wall is

a liejust painted drywall in front of empty space between the studs), or simply a pathological lack of personal agency, but it’s hard to believe you can change anything dissatisfactory about your life if you can’t change a 9V battery.Making and doing things, even when you don’t have to, is practice in believing that you can change your own world. It’s weightlifting for agency. You can outsource the making of your physical world, but social worlds — the arrangement of your family life, your personal relationships, the organizations and institutions you’re involved in — must be created by the participants themselves. A good society would be one where the default “builder-grade” scripts lead to human flourishing, but unfortunately that isn’t ours, so you have to be able to decide on your own changes. Start practicing now: find one little thing about your physical environment that annoys you and fix it. Put the new toilet paper roll actually on the holder. Replace the burned-out lightbulb. Hang the artwork that’s listing drunkenly against the wall. Pull some weeds. And then, once you’ve warmed up a little bit, go and make something new.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-22.

1. They’re oak dining chairs, probably (judging by the construction) about a hundred years old, and they looked a lot better on Facebook Marketplace than in real life. When I showed up to buy them, the sellers turned out to be an elderly couple moving to assisted living in six hours; they admired my baby and showed me pictures of their grandchildren and explained they had inherited the chairs from the wife’s mother, who in turn had gotten them from her friend’s mother, and by this point I couldn’t really say “yeah I can tell” and leave, so home they came. When I took apart the seats to recover them I discovered the original horsehair padding and some extremely questionable techniques applied over the years, but anyway now my chairs have eight-way hand-tied springs and I have some new calluses.

August 25, 2023

Only an extreme right-wing bigot would say that “BDSM is not for four-year-olds”

Noted extreme right-wing arch-conservative Brendan O’Neill somehow seems to think that the full panoply of LGBT sexual identities are not appropriate for the pre-school set:

BDSM is not for four-year-olds. Apparently, that’s a controversial statement these days. Only a bigot would want to protect little kids from images of old blokes in fetish gear snogging the faces off each other in public. If you think under-fives should be reading books about hungry caterpillars or tigers coming for tea, not books featuring pictures of ageing men in dog collars and studded leather underwear, you’re a queerphobe and you need to pipe down.

Truly we have reached the seventh circle of woke lunacy. This week it was reported that a mum and dad in Hull in the north of England pulled their four-year-old daughter from a pre-school after she was shown a book called Grandad’s Pride which contains illustrations of “men who are partially naked in leather bondage gear”. The pre-school’s response? According to the mum and dad, it branded them “bigots”. Yes, who else but a hateful phobe would want to stop a toddler from seeing a tattooed, half-naked, grey-bearded homosexual kissing his boyfriend?

Grandad’s Pride is written by Harry Woodgate, an award-winning children’s author who uses they / them pronouns. Of course he does. Or of course they do. Whatever. It tells the story of a girl called Milly, who is playing in her gramps’ attic one day when she happens upon an old Pride flag. She asks what it is and grandad suggests they organise their own Pride march in the village. As you do. Then come the iffy illustrations: old men in fetish gear; a “trans man” (ie, woman) with mastectomy scars under her nipples; an activist in a spiked dog collar waving a placard that says: “Break the cis-tem”. And you thought Where the Wild Things Are was scary.

You don’t have to be a prude to think this is ridiculous bordering on sinister. My view is that consenting adults should do whatever they want. Wear chafing leather trousers, pierce your cock, whip your friends in dim-lit dungeons. It’s not my cup of tea, but knock yourselves out. But it’s not for kids! No four-year-old should be looking at illustrations of a mutilated woman who now identifies as a “man” or of pensioners in leather suspenders. And it doesn’t make you Mary Whitehouse to say so. When you read to little kids, you want them to ask questions like, “Can we have a tiger over for tea?”, not: “Why does that man have stitches on his chest?”

One of the most frustrating things for freedom-lovers like me is that when we raise questions about age-inappropriate woke crap in schools, we get lumped with the religious right or PC fanatics who previously waged war on classic texts like Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (too much talk about menstruation, apparently) and John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (too many utterances of the n-word). Nonsense. Of course schoolkids should read Blume and Steinbeck. Teens in particular should be expected to engage with challenging texts, even ones that contain racial epithets or girls eagerly awaiting their first period. Schools should err on the side of being open with literature, though let’s hope they don’t start stocking American Psycho or The 120 Days of Sodom.