Practical Engineering

Published 8 Nov 2022How a nuclear blast in the upper atmosphere could disable the power grid.

(more…)

March 7, 2023

How Would a Nuclear EMP Affect the Power Grid?

QotD: The Stoic view of beauty

Stoics were thoroughgoing materialists. Even the soul, the life-force, whatever you want to call it (their term was pneuma), was conceived of as a physical thing: Elemental fire. (This is another reason I wanted to start with Stoicism. You can build a fine life, and a strong community of men, with, say, Ignatius of Loyola, but since this is the Postmodern world anything overtly religious will turn off the very people who need it most. Stoicism is tailor-made for modern “atheists” (just don’t tell Marcus himself that)).

Like all materialists, then, Stoics had a real problem with things like beauty. If you’re a materialist, Beauty is either a refutation of your theory, or a tautology (“certain arrangements of atoms produce chemical reactions that our brains interpret as pleasant” is just a fancy way of saying “beautiful things are beautiful because they’re beautiful”). Back in grad school, in one of the deepest, darkest, most dungeon-like corners of the university’s book morgue, I discovered Ayn Rand’s attempt at an Objectivist aesthetics. Her conclusion, stripped of her inimitable self-congratulatory prose, is here:

At the base of her argument, Rand asserts that one cannot create art without infusing a given work with one’s own value judgments and personal philosophy. Even if the artist attempts to withhold moral overtones, the work becomes tinged with a deterministic or naturalistic message. The next logical step of Rand’s argument is that the audience of any particular work cannot help but come away with some sense of a philosophical message, colored by his or her own personal values, ingrained into their psyche by whatever degree of emotional impact the work holds for them.

Rand goes on to divide artistic endeavors into “valid” and “invalid” forms …

In other words, there’s no art, only propaganda. Looks like ol’ Marcus really missed a trick, statecraft-wise, doesn’t it?

Severian, “On Fine Writing Etc.”, Everyday Stoicism, 2020-05-04.

March 6, 2023

Britain’s Free Speech Union at three

Earlier this month, Toby Young’s Free Speech Union celebrated its third birthday:

Toby Young founded the Free Speech Union in early 2020, and on Wednesday, 1 March a party was thrown to celebrate the organisation’s third birthday. The delicate baby born just before the Covid-19 lockdowns has grown into a boisterous, disruptive toddler that stomps about the political scene breaking things.

Over 100 people came to the In and Out on St James’s Square to enjoy the FSU’s success, including Professor Nigel Biggar, whose book Colonialism was effectively cancelled by Bloomsbury when the publisher’s executives decided that “public feeling” was against its publication. The legal profession was well-represented — Francis Hoar acted as counsel in various legal challenges for those damaged by the government’s lockdowns. He was heard to complain that the Covid-19 inquiry under Lady Hallett had granted core participant status to various bereaved family groups and those suffering from long Covid, but had denied it to the hospitality and other businesses which had been pushed into bankruptcy. Other attendees included Matthew Elliott, who led Vote Leave; Matt Ridley, the author of The Rational Optimist; and Adam Afriye MP. The FSU has been remarkably successful in raising funds, and there was a good turn out of donors like Lady Bell, the widow of Bell Pottinger founder Lord Bell of Belgravia.

Young told the room what his creation had achieved in its short life so far — a paying membership of 11,000; more than 2,000 cases taken on; a staff of 16 including eight full time employees — and talked about his political campaigns. Currently in his crosshairs is the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act) Bill, which has been tabled by Vera Hobhouse MP and is supported by the government. The Equality Act already imposes a duty on employers to stop their workers from being harassed by other employees in relation to a protected characteristic such as sexual orientation, disability or age. Hobhouse’s bill will extend that duty so companies can be liable for third parties’ harassing actions, unless the employer has taken “all reasonable steps” to protect them.

It is almost certain to have a chilling effect on free speech in the workplace, as well as creating additional costs which will have to be passed on to consumers — perhaps good news for HR departments, probably bad news for everyone else. The FSU hopes to see amendments proposed to the bill which will need to have public consultation, thereby delaying its parliamentary progress. It is hoped that the delay will prove fatal.

Updating Pascal’s Wager

David Friedman discusses moral realism and comes up with an improvement to Blaise Pascal’s famous wager:

Blaise Pascal famously argued that one ought to believe in the Catholic faith because the enormous payoff if it was true, heaven instead of hell, made it in your interest to believe even if you thought the probability that it was true was low.

There are three problems with the argument. The first is that belief is not entirely a matter of choice — I cannot make myself believe that two plus two equals five however much I am offered for doing so. The second is that belief motivated not by love of God but by love of self, the desire to end up in Heaven instead of Hell, might not qualify you for admission. The third is that the argument applies to many doctrines other than Catholicism and so gives you no way of choosing among Christian sects or between Christianity and alternative religions, short of somehow estimating the probability that each is true and the associated payoff and choosing the one with the highest expected return.

I, however, have an improved version of the argument free from all of those problems, an argument not for Christianity but for moral realism.

One explanation of our moral feelings is that right and wrong are real and our beliefs about right and wrong at least roughly correct. The other is that morality is a mistake; we have been brainwashed by our culture, or perhaps our genes, into feeling the way we do, but there is really no good reason why one ought to feed the hungry or ought not to torture small children.

If morality is real and you act as if it were not, you will do bad things — and if morality is real you ought not to do bad things. If morality is an illusion and you act as if it were not you may miss the opportunity to commit a few pleasurable wrongs but since morality correlates tolerably, although not perfectly, with rational self interest, the cost is unlikely to be large. It follows that if you are uncertain which of the two explanations is correct you ought to act as if the first is.

No god is required for the argument, merely the nature of right and wrong, good and evil, as most human beings intuit them. The fact that you are refraining from evil because of a probabilistic calculation does not negate the value of doing so — you still haven’t stolen, lied, or tortured small children. One of the odd features of our intuitions of right and wrong is that they are not entirely, perhaps not chiefly, judgements about people but judgements about acts.

The Rise and Fall of Fast Food Architecture

Stewart Hicks

Published 3 Nov 2022What happened to McDonald’s? Their restaurants used to be so iconic. It was impossible to mistake one, for say, a Wendy’s. Distinguished architecture used to be an important part of a brand’s identity. But today, fast food restaurant’s all look the same. Bland grey boxes. The great convergence toward this standard has been called “Chipotle-ification”. In this video, we trace the changing restaurant designs of McDonald’s, from the iconic golden arch era to the soulless boxes of today. We break down the architecture and the forces at play in the great homogenization of fast food architecture.

(more…)

QotD: The pastries of the wider paradonut family

When people say “I’d like a donut”, #Science indicates that Actually, they don’t want a donut at all. They say donut, but they really mean a pastry from the paradonut family.

Exhibit A: The Coffee Roll — Phasers on Star Trek have three settings: Stun, Kill, and Coffee Roll.

Exhibit B: The Eclair — From the French for “lightning”, the eclair was invented by a psychiatrist as a delicious alternative to electroshock therapy for schizophrenics. Because when you’re eating an eclair, you can’t deny the marvelous cream-filled reality you’re actually present in.

Exhibit C: The Cheese Danish — Cheese Danishes have a mix of flavors and textures that make them, in scientific terms, “a gang-bang for your face”.

Exhibit D: The Bear Claw — The bear claw is the ugly, bewarted King Pimp of the pastry shop window, with a dozen smaller, more effeminate donuts it’s turned into its sad little bitches and tricks following behind it.

Exhibit E: The Apple Fritter — The so-called “Emperor of Pastries” makes your stupid little glazed donut look sad and weak like Barack Obama’s gay arms.

Exhibit F: The Cinnamon Bun — Cinnamon Buns have been proven to be responsible for America’s obesity epidemic and diabetic crisis, and also totally worth it.

Bonus: Worst Donuts

1. Jelly Donuts — Jelly donuts are always what’s left after people eat the real donuts. Jelly donuts are consolation prizes for losers who came late. They taste like failure for a reason. If you’re eating a jelly donut, that’s because you’re not a competitor and you don’t have any friends to set aside a good donut for you.

2. Plain Donuts — Plain donuts are also called “not donuts” or “ring-shaped bread”. Plain donuts were invented for parents who don’t love their children. They are also sometimes put out as bait for poisoning rats, though they have a 75% failure rate. Rats don’t like them either. Sometimes a poisoned plain donut will be found intact, with a dead rat next to it — rats will lick the poison off the plain donut while avoiding the plain donut itself. According to Leviticus, you are supposed to pay the dowry of an ugly woman in plain donuts.

3. Powdered Sugar Donuts — Powdered sugar donuts are made primarily by mental degenerates employed by donut shops as charity hires. They are sometimes called “Retard Donuts”. To compare powdered sugar donuts to the Holocaust would be to trivialize the horror of powdered sugar donuts.

Ace, “Science Proves That The Best Donuts Are Actually Non-Donuts”, Ace of Spades H.Q., 2017-06-17.

March 5, 2023

The clear drawbacks of depending too much on oral history

In The Line, Jen Gerson explains why you need to exercise caution when dealing with oral traditions:

Lac La Croix Indian Pony stallion – Mooke (Ojibway for – he comes forth), October 2008.

Photo by Llcips09 via Wikimedia Commons.

A BBC travel feature published several weeks ago had the hallmarks of a classic progressive narrative. It was the tale of the “endangered Ojibwe spirit horse; the breed, also known as the Lac La Croix Indian pony, is the only known indigenous horse breed in Canada.”

The spirit horse was reduced to near extinction by European settlers who treat these magical creatures, deemed “guides and teachers”, as a mere nuisance to be culled and eliminated in favour of more profitable animals like cattle, or so the telling goes. A native breed of a beloved animal struggling to survive in the face of voracious colonial settlers.

Someone call James Cameron.

Unless you know a little evolutionary history, that is. In which case, you will already be aware that this story is pure pseudoscientific hokum.

Look, no one likes to be disrespectful about sensitive matters where the legitimately oppressed and aggrieved claims of First Nations peoples are concerned. This is a nation that is struggling to come to terms with its own horrific colonial past. This process is taking on many forms: witness the applause granted to singer Jully Black, who recently amended the national anthem “our home on native land”. Or, perhaps, the calls by one NDP MP to combat residential school denialism by passing new laws on hate speech — which would make questioning certain narratives not only an act of heresy, but also a literal crime.

Listening to stories, and respecting lived experiences and oral histories Indigenous people at the core of Canadian history and identity has given a new credibility to the traditional knowledge of First Nations people in academia, media, and in society at large.

But the story of the Ojibwe spirit horse is a clear example of the limits of oral history.

The horses now roaming the plains of North America are not a native species. The horse did evolve on this continent before migrating to Asia and Europe. However, the North American breed is believed to have been extirpated about 10,000 years ago (or thereabouts) during a mass extinction event that wiped out almost all large land mammals.

There is some evidence that isolated pockets of a native horse breed may have survived in North America much later than this, but the horses roaming about today are descended from those that were brought from Europe after the 15th century.

Of course, science is always evolving, but the overwhelming bulk of genetic and archeological evidence to date supports this theory. The native North American horse is long, long gone. The bands of horses freely wandering the backcountry are not wild, but feral; they’re the product of escaped or abandoned horse stock of distant European origin.

MacArthur and Nimitz Go Head-to-Head – Week 236 – March 4, 1944

World War Two

Published 4 Mar 2023The American attacks against the Admiralty Islands are successful, but this causes real tensions between commanders Douglas MacArthur and Chester Nimitz. Much of this week is taken up by planning and meetings on both sides — Adolf Hitler plans the occupation of Hungary, Josef Stalin plans new offensives in Ukraine, and the Allies plan to reconfigure their whole front in Italy. It’s all the prelude to an explosion of action.

(more…)

Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and the Greek Myths

toldinstone

Published 20 Aug 2021Did dinosaur fossils inspire the mythical griffin? Did mammoth bones shape the story of the Gigantomachy? Were the cyclopes modeled on the skulls of dwarf elephants? This video investigates some of the fascinating intersections between fossils and the Greek myths.

This video is part of a collaboration with @NORTH 02 Check out their video “Scimitar Cats, Cave Bears, and Behemoths” for more on the fossils that so fascinated the ancient Greeks and Romans: https://youtu.be/lpU-F3EQ4v4

(more…)

QotD: The role of the “big” landowners in pre-modern farming societies

What generally defines our large landholders is their greater access to capital. Now we don’t want to think of capital in the sort of money-denominated, fungible sense of modern finance, but in a very concrete sense: land, infrastructure, animals, and equipment. As we’ll see, it isn’t just that the big men hold more of this capital, but that they hold fundamentally different sorts of capital and often use it very differently.

Of course this begins with land. The thing to keep in mind is that prior to the modern period […] the vast majority of economic activity was the production of the land. That meant that land was both the primary form of holding wealth but also the main income-producing asset. Consequently, larger land holdings are the assets that enable the accumulation of all of the other kinds of capital we’re discussing. By having more land – typically much more land – than is required to feed a single household, these larger farmers can […] produce for markets and trade, enabling them to afford to acquire labor, animals, equipment and so on. Our subsistence farmers of the last post, focused on producing for survival, would be hard-pressed to acquire much further in the way of substantial capital.

The next most important category is generally animals, particularly a plow team […] while our small subsistence farmers may keep chickens or pigs on some small part of the pasture they have access to, they probably do not have a complete plow-team for their own farm […]. Oxen and horses are hideously expensive, both to acquire but also to feed and for a family barely surviving one year to the next, they simply cannot afford them. They also do not have herds of animals (because their small farms absolutely cannot support acres of pasturage) and they probably have limited access to herdsmen generally (that is, transhumant pastoralists moving around the countryside) because those fellows will tend to want to interact with the community leaders who are, as noted above, the large landholders. All of which is to say that while the small farmers may keep a few animals, they do not have access to significantly large numbers of animals (or humans), which matters.

The first impact of having a plow-team is fairly obvious: a plow drawn by a couple of oxen is more effective than a plow pushed by a single human. That means that a plow-team lets the same amount of farming labor sow a larger area of land […]. It also allows for a larger, deeper plow, which in turn plows at a greater depth, which can improve yields […]. You can easily see why, for a landholder with a large farm, having a plow-team is so useful: whereas the subsistence farmer struggles by having too much labor (and too many mouths to feed) and too little land, the big landholder has a lot of land they are trying to get farmed with as little labor as possible. And of course, more to the point, the large landholder has the wealth and acreage necessary to buy and then pasture the animals in the plow-team.

The second major impact is manure. Remember that our farmers live before the time of artificial fertilizer. Crops, especially bulk cereal crops, wear out the nutrients in the soil quite rapidly after repeated harvests, which leaves the farmer two options. The first, standard option, is that the farmer can fallow the field (which also has the advantage of disrupting certain pest life-cycles); depending on the farming method, fallowing may mean planting specific plants to renew the soil’s nutrients when those plants are uprooted and left to return to the soil in the field or it may mean simply turning the field over to wild plants with a similar effect. The second option is using fertilizer, which in this case means manure. Quite a lot of it. Aggressive manuring, particularly on rich soils which have good access to moisture (because cropping also dries out the soil; fallowing can restore that moisture) allows the field to be fallowed less frequently and thus farmed more intensively. In some cases it allowed rich farmland to be continuously cropped, with fairly dramatic increases in returns-to-acreage as a result. And by increasing the nutrients in the soil, it also produces higher yields in a given season.

Now the humans in a farming household aren’t going to generate enough manure on their own to make a meaningful contribution to soil fertility. But the larger landholders generally have two advantages in this sense. First, because their landholdings are large, they can afford to turn over marginal farming ground to pasture for horses, cattle, sheep and so on; these animals not only generate animal products (or prestige, in the case of horses), they also eat the grass and generate manure which can be used on the main farm. The second way to get manure is cities; unlike farming households, cities do produce sufficient quantities of human waste for manuring fields. And where small subsistence farmers are unlikely to be able to buy that supply, large landholders are likely to be politically well-connected enough and wealthy enough to arrange for human waste to be used on their lands, especially for market oriented farms close to cities. And if you just stopped and said, “wait – these guys were paying for human waste?” … yes, yes they sometimes did (and not just for farming! Check out how saltpeter was made, or what a fuller did!).

Finally, there’s the question of infrastructure: tools, machines and storage. The large landholder is the one likely to be able to afford to build things like granaries, mills and so on. Now there is, I want to note, a lot of variation from place to place about exactly how this sort of infrastructure is handled. It might be privately owned, it might be owned by the village, but frequently, the “village mill” was actually owned by the large landholder whose big manor overlooked the village (who may also be the local political authority). And while we’re looking at grain, other agricultural products which don’t store as well or as easily might need to be aggregated for transport to market and sale, a process where the large landholder’s storage facilities, political standing and market contacts are likely to make him the ideal middleman. I don’t want to get too in the weeds (pardon the pun) on all the different kinds of infrastructure (mills for grains, presses for olives, casks for wine) except to note that in many cases the large landholder is the one likely to be able to afford these investments and that smaller farmers growing the same crops nearby might well want to use them.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Bread, How Did They Make It? Part II: Big Farms”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-07-31.

March 4, 2023

Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning

In The Critic, Robert Lyman reviews a recent book offering a rather more nuanced view of the British empire:

The book is a careful analysis of empire from an ethical perspective, examining a set of moral questions. This includes whether the British Empire was driven by lust or greed; whether it was racist and condoned, supported or encouraged slavery; whether it was based on the conquest of land; whether it entailed genocide and or economic exploitation; whether its lack of democracy made it illegitimate; and whether it was intrinsically or systemically violent.

Biggar’s proposition is simple: that we look at Britain’s history without assuming the zero-sum position that imperialism and colonialism were inherently bad, that motives and agency need to be considered and that good did flow from bad, as well as bad from good.

Whether he succeeds depends on the reader’s willingness to appreciate these moral or ethical propositions, and to re-evaluate accordingly. In my view, he has mounted a coolly dispassionate defence of his proposition, challenging the hysteria of those who suggest that the British Empire was the apotheosis of evil. Biggar’s calm dissection of these inflated claims allows us to see that they say much more about the motivations, assumptions and political ideologies of those who hold these views than they do about what history presents to us as the realities of a morally imperfect past.

He reminds us that British imperialism had no single wellspring. Most of us can easily dismiss the notion that it was a product of an aggressive, buccaneering state keen to enrich itself at the expense of peoples less able to defend themselves. Equally, it is untrue that economic motives drove all imperialist or colonial endeavour, or that economics (business, trade and commerce) was the primary force sustaining the colonial regimes that followed.

As Biggar asserts, both imperialism and colonialism were driven from different motivations at different times. Each ran different journeys, with different outcomes depending on circumstances. The assertion that there is a single defining imperative for each instance of imperial initiative or colonial endeavour simply does not accord with the facts.

Whilst other issues played a part, it was social, religious and political motives which drove the colonial endeavour in the New World from the 1620s: security and religion drove the subjugation of Catholic (and therefore Royalist) Ireland in the 1650s; social and administrative factors led to the settlement in Australia from 1788; and social and religious imperatives drove the colonisation of New Zealand in the 1840s.

In circumstances where trade and the security of trade was the primary motive for imperialism — think of Clive in the 1750s, for example — a wide variety of outcomes ensued. Some occurred as a natural consequence of imperialism. In India, Clive’s defeat of the Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah in 1757 was in support of a palace coup that put Siraj’s uncle Mir Jafar on the throne of Bengal, thus allowing the East India Company the favoured trading status that Siraj had previously rejected.

This led in time to the Company taking over the administrative functions of the Bengal state (zamindars collected both rents for themselves and taxes for the government). Seeking to protect its new prerogatives, it provided security from both internal (civil disorder and lawlessness) and external threats (the Mahratta raiders, for example). The incremental, almost accidental, accrual of power that began in the early 1600s stepped into colonial administration 150 years later, leading to the transfer of power across a swathe of the sub-continent to the British Crown in 1858.

Biggar’s argument is that, running in parallel with this expansion came a host of other consequences, not all of which can be judged “bad”. We may not like what prompted the colonial enterprise at the outset (not all of which was morally contentious, such as the need to trade), but we cannot deny that good things, as well as bad, followed thereafter.

Persistent fantasies about lost Ice Age civilizations

When I was a teen, there seemed to be a lot of pop-sci books on the racks at our local variety store pushing various notions about “highly advanced” but lost civilizations, often attributing things like UFO sightings to these imagined prehistoric groups and tying various conspiracy theories back to them. At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander argues against today’s fans of such unlikely scenarios:

You can separate these kinds of claims into three categories:

- Civilizations about as advanced as the people who built Stonehenge

- Civilizations about as advanced as Pharaonic Egypt

- Civilizations about as advanced as 1700s Great Britain

The debate is confused by people doing a bad job clarifying which of these categories they’re proposing, or not being aware that the other categories exist.

2 and 3 aren’t straw men. Robert Schoch says the Sphinx was built in 9700 BC, which I think qualifies as 2. Graham Hancock suggests “ancient sea kings” drew the Piri Reis map which seems to depict Antarctica; anyone who can explore Antarctica must be at least close to 1700s-British level.

I think there’s weak evidence against level 1 civilizations, and strong evidence against level 2 or 3 civilizations.

Argument 1: Where Are The Sites?

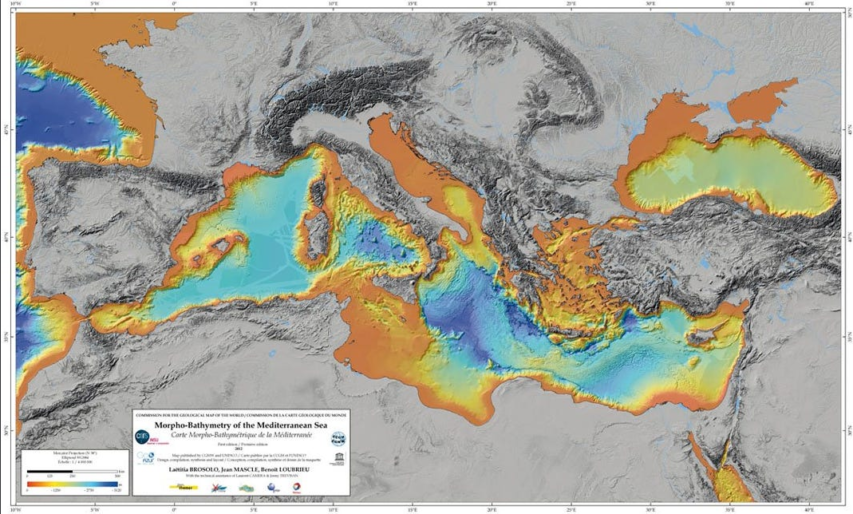

Supporters of ice age civilizations argue that sea level rose 120 meters as the Ice Age glaciers melted, flooding low-lying coasts and destroying any evidence of coastal civilizations.

Areas likely above water during the Ice Age are in orange-brown (source)

What would happen to the ancient civilizations we know about if sea level rose an additional 120m? We would lose Babylon, Rome, and most of Egypt. But:

- The Acropolis of Athens is 150m above sea level, and would be preserved for future archaeologists. Sparta (200m) and Thebes (250m) would also be fine.

- The Hittite capital of Hattusa is almost 1,000m above sea level and would be totally unaffected.

- The two biggest cities in Assyria, Ashur and Nineveh, would both make it.

- Zhengzhou, the capital of the Shang in ancient Chinese, would survive.

- Mohenjo-Daro would sink, but Harappa would be fine.

- Basically nobody in Elam/Medea/Persia would even notice.

- The top 80m of the Great Pyramid would rise above the waterline, forming a little island. The part of the Pyramid above the water would still be taller than the entire Leaning Tower of Pisa. It would be pretty hard to miss!

So a 120m sea level rise wouldn’t be enough to wipe out evidence of our crop of ancient civilizations, and shouldn’t be enough to wipe out evidence of a previous crop, unless they had a very different geographic distribution than ours.

Corruption? In Arizona? It’s more disturbing than you think

Elizabeth Nickson digs into the allegations of massive corruption in the state of Arizona:

Governor Katie Hobbs speaking with attendees at a Statehood Day ceremony in the Old Senate Chambers at the Arizona State Capitol building in Phoenix, Arizona on 14 February, 2023.

Photo by Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons.

One always likes a unifying theory, particularly one that explicates a thorny mystery rigorously ignored by the super-culture, by which I mean the world that the educated and financially secure occupy.

For instance: why was the preponderance of evidence of election fraud ignored by the courts? How did corruption in city and county governments take hold? Why are desperate people flooding the borders unchecked? Why is human and child sex trafficking so prevalent and not stopped? Why are we permitting our fellow citizens to become human wrecks in open-air drug markets? Why are our biggest cities degrading? Why, in so many cities, is middle class housing out of reach for the middle class?

The answer may be because a significant number of elected and appointed officials have been bribed by cartels and other criminal enterprises like the CCP or Asian gangs, like the ones operating in Vancouver, Seattle and San Francisco. And they are bribed through single family housing, bidding up and up and up the price of real estate.

Late last week, an extraordinary hearing took place in the Arizona Senate, whiphanded by Liz Harris, the chair of the committee investigating election fraud in Arizona. Only Harris expected the last presentation, and it was given by a woman we have all met in the nether worlds of finance when we are re-mortgaging, insuring, reinsuring, or investing in a local enterprise.

She is competent, reductionist, modest, and honest to a fault. She knows the paperwork she slides in front of you for signature, willing to describe every phrase in exhaustive detail.

One of those invisible people upon whom the entire system relies.

Jacqueline Breger was a single mother who owns her own insurance company, has multiple degrees, in accounting, an MBA, and various other necessary finance-industry certifications. She works with her husband1, an investigative attorney named John Thaler.

The story she told had half of America transfixed. Her testimony was based on that of a whistleblower from the Sinaloa cartel given during an application for witness protection, and the subsequent acquisition of 120,000 court documents that prove the case.

Nobody could believe it. Even those who would benefit by it if it were true, didn’t believe it. In the dozen or so interviews that followed the testimony, questions were barked at her and her employer with no small measure of hostility. Rick Santelli of CNBC looked as if all his hair was standing on end.

It starts this way:

In 2006, members of the Sinaloan cartel were arrested, tried and convicted for money laundering through single family homes in Illinois, Iowa and Indiana.

In 2014, Berger’s partner, John Thaler was asked to review the Sinaloan cases in Illinois, Indiana and Iowa and investigate whether the cartel had moved its enterprise to Arizona. Currently, the couple are working with several States Attorneys, the Attorneys General of New Mexico and California, and members of the FBI.

So this is a theory that requires attention.

1. Thaler and Berger are married. Thaler’s ex-wife was the Sinaloan cartel member who requested witsec, and decanted the evidence which triggered the acquisition of the thousands of forged and fake documents. Much of the story is focused on the domestic drama, as if domestic drama were not a part of everyone’s life at one time or another. I am more interested in discovering the truth of the matter.