When we started this series, we had two myths, the myth of Spartan equality and the myth of Spartan military excellence. These two myths dominate the image of Sparta in the popular consciousness, permeating game, film and written representations and discussions of Sparta. These myths, more than any real society, is what companies like Spartan Race, games like Halo, and – yes – films like 300 are tapping into.

But Sparta was not equal, in fact it was the least equal Greek polis we know of. It was one of the least equal societies in the ancient Mediterranean, and one which treated its underclasses – who made up to within a rounding error of the entire society by the end – terribly. You will occasionally see pat replies that Sparta was no more dependent on slave labor than the rest of Greece, but even a basic demographic look makes it clear this is not true. Moreover our sources are clear that the helots were the worst treated slaves in Greece. Even among the Spartiates, Sparta was not equal and it never was.

And Sparta was not militarily excellent. Its military was profoundly mediocre, depressingly average. Even in battle, the one thing they were supposed to be good at, Sparta lost as much as it won. Judging Sparta as we should – by how well it achieved strategic objects – Sparta’s armies are a comprehensive failure. The Spartan was no super-soldier and Spartan training was not excellent. Indeed, far from making him a super-soldier, the agoge made the Spartans inflexible, arrogant and uncreative, and those flaws led directly to Sparta’s decline in power.

And I want to stress this one last time, because I know there are so many people who would pardon all of Sparta’s ills if it meant that it created superlative soldiers: it did not. Spartan soldiers were average. The horror of the Spartan system, the nastiness of the agoge, the oppression of the helots, the regimentation of daily life, it was all for nothing. Worse yet, it created a Spartan leadership class that seemed incapable of thinking its way around even basic problems. All of that supposedly cool stuff made Sparta weaker, not stronger.

This would be bad enough, but the case for Sparta is worse because it – as a point of pride – provided nothing else. No innovation in law or government came from Sparta (I hope I have shown, if nothing else, that the Spartan social system is unworthy of emulation). After 550[BC], Sparta produced no trade goods or material culture of note. It produced no great art to raise up the human condition, no great literature to inspire. Despite possessing fairly decent farmland, it was economically underdeveloped, underpopulated and unimportant.

Athens produced great literature and innovative political thinking. Corinth was economically essential – a crucial port in the heart of Greece. Thebes gave us Pindar and was in the early fourth century a hotbed of military innovation. All three cities were adorned by magnificent architecture and supplied great art by great artists. But Sparta, Sparta gives us almost nothing.

Sparta was – if you will permit the comparison – an ancient North Korea. An over-militarized, paranoid state which was able only to protect its own systems of internal brutality and which added only oppression to the sum of the human experience. Little more than an extraordinarily effective prison, metastasized to the level of a state. There is nothing of redeeming value here.

Sparta is not something to be emulated. It is a cautionary tale.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VII: Spartan Ends”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-27.

August 15, 2022

QotD: Sparta – the North Korea of the Classical era

August 14, 2022

Book Review: FN Mauser Rifles by Anthony Vanderlinden

Forgotten Weapons

Published 2 Jan 2017Buy the book here: http://www.fnbrowning.com/fn-mauser-r…

When I was waiting for my copy of Anthony Vanderlinden’s new book FN Mauser Rifles to arrive, I was expecting a typical sort of dry reference work. You know, the sort of thing that is essential for looking up details like the serial number range for a specific contract, or the sling swivel location on some specific nation’s version of a rifle. When the book arrived and I cracked it open, I found something quite different.

What I found was an authentically engrossing history of Belgium, the Fabrique Nationale company, and the rifles it produced. It would have been a savvy move to deliberately expound on the context of FN’s Mausers to make them more interesting (let’s be honest; Mauser contract variations are not the most riveting subject in arms history), but I think the book took this path because of the author’s genuine passion for the subject and a desire to share that passion with others. Good grief, the man owns a 1926 FN car! If that’s not devotion to a subject, I don’t know what is (and it’s really cool!).

Anyway, the first half of the book is a tale of Belgian history and arms production. The trials that led to the adoption of the 18

9189 Mauser and the subsequent formation of the FN conglomerate by the preeminent armsmakers of Liege in order to secure a contract to make those 189189s. The production leading up to WWI, and the Belgian response to that war, including production in the United States and England. The company’s recovery after the war, including its efforts in the automotive industry. The buildup to WWII, and the response to yet another German occupation. Sabotage of German production. Recovery after that war as well, and FN’s role in post-war Europe as Mauser production came to an end. And throughout this tale, the simultaneous story of the Congo Free Sate as it became the Belgian Congo and took part in Belgium’s trials and tribulations.In the more technical sections of the book, Vanderlinder presents information that has heretofore been pretty hazy, like the actual differences between FN Mauser model designations, and exactly who ordered what and when. He also provides excellent detail on the manufacture, repair, and later conversions of the Model 18

9189 rifles for the Belgian military as well as the Congolese armed forces.As you have probably realized by this point, I found the book an excellent and compelling read … not the sort of thing one would normally expect from this subject matter. You don’t need to be an avid enthusiast of FN or Belgian history to appreciate it. Quite the opposite, in fact — if you (like most people) have only the most cursory knowledge of the subject, it is an excellent way for you to really find an appreciation for the company and country. Just be warned that the cover price doesn’t include the rifles you will want to buy once you’ve started reading!

FN Mauser Rifles is available directly from the publisher (who is also the author, but this is not a self-published work) at www.FNBrowning.com. Ordering there instead of from other dealers will get you an autographed copy, which is a nice bonus.

(more…)

QotD: The 2016 US election was a rejection of the media

Here’s a surprising report: President Trump’s support is actually rising after his attack on “The Squad”.

The rise in support isn’t the surprising part. The surprising part is that the Media still find this surprising.

Not to toot my own horn too much here, but I’ve been writing about this since 2015 … “Make America Great Again” was the Trump campaign’s official slogan, but unofficially — and much, much more effectively — it was: “Fuck the Media”. The 2016 election is known far and wide as “The Great Fuck You”, but somehow, some way, almost everyone still fails to grasp that it wasn’t the Democrats who got told to fuck off. It wasn’t even the “Progressives”. It was The Media. The Great Fuck You was aimed entirely at the Media.

Severian, “Which Hand Holds the Whip?”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-07-17.

August 13, 2022

The Great Escape from a Death Factory – WAH – August 7, 1943

World War Two

Published 12 Aug 2022While enslavement, and mass murder continues unabated in August 1943, at the Treblinka Death Factory the forced laborers decide that enough is enough, and bring battle to the SS in a daring escape attempt.

Huge thanks to Purple Purple, Steven Yarnell, Pieter Kleij and Ruben Alikhanyan for their support during the episode premiere.

(more…)

The lure of old wines

In The Critic, Henry Jeffreys admits his continuing love for mature wines, even past the point most people would consider them drinkable:

For some people wine appreciation is like big game hunting. It’s about ticking off the prizes: Latour, Petrus, Romanee Conti. Whereas for others it’s about chasing unicorns, looking for mythical wines so rare that they are almost impossible to obtain. I don’t have the money for either, but even if I did, I still think I would take the greatest pleasure in opening a strange old bottle and being surprised by how delicious it is.

I’m fortunate in having friends and relatives who think wine is more for keeping than for drinking. When my grandfather died, we inherited all kinds of strange things that he’d been saving including a half bottle of 1937 Army & Navy claret.

I’ve certainly never had the deep pockets to go after any of those tip-top wines, although I used to be able to go to LCBO wine tasting events where there’d occasionally be opportunities to try a few ultra-expensive wines (Petrus, Château Margaux, Nuits-Saint-Georges, Chassagne-Montrachet, Puligny-Montrachet, etc.). If I’m totally honest, in a few of those cases, the bouquet of the wine promised far more than the taste could deliver … I appreciate and enjoy better quality wines, but I don’t taste enough difference between a $50 bottle and a $500 bottle to justify paying the premium.

Oddly certain people get quite upset at lovers of very old wine. On Twitter recently a sommelier wrote “your taste sucks” to someone who expressed an enjoyment of such wines.

The French look at this peculiarly British habit as close to necrophilia. Americans, too, drink vintage port after a couple of years rather than waiting a generation as is customary.

There’s something magical about what decades can do to a wine. Quite austere clarets become heady and exotically-spiced while sweet wines begin to taste dry. I also relish the flavours that some might find less appealing: the tang of vinegar, the cooked taste of caramel and the whiff of sherry in wines that definitely are not sherry.

Maybe my taste sucks too but sometimes I prefer a wine to be old than to be particularly good. You adjust your palate, it’s like having a conversation with an elderly relative who’s a bit deaf but with great stories to tell.

Mysterious Home Features No Longer Used

Rhetty for History

Published 22 Apr 2022Home designs have changed a lot over the years and so have the features. In this video we will take a look at some of the mysterious features no longer used in new homes. You may run across these if you purchase an old home or you visit one.

(more…)

QotD: Erich von Manstein

One parallel between the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the conduct of the Second World War that has hitherto escaped notice concerns the relationship between the dictator and his generals. Just as the German General Staff obeyed Hitler’s orders, even when they knew him to be leading them not only to defeat but to depravity, so the Russian high command has capitulated to Putin despite realising that his war was not only a mistake but a crime.

In the Britain of the Sixties, a certain mystique still attached to the generals of the Third Reich. In their stylish uniforms and their gleaming jackboots, they had swaggered. Only two, Keitel and Jodl, were executed at Nuremberg; the rest got away with murder.

Even some of those who were convicted of war crimes had friends in high places. One of the most prominent was Erich von Manstein, the architect of many German victories both in the Battle of France and on the Eastern front. He was also complicit in the genocide of more than a million Jews and others by the Nazi Einsatzgruppen in Ukraine.

Yet Churchill was among those who successfully campaigned to have Manstein’s 18-year sentence reduced to 12, of which he served only four.

Manstein’s memoir Verlorene Siege (translated as Lost Victories) appeared in 1958, a key text in the mythology that depicted the Wehrmacht as “clean” and laid the blame for war crimes on Hitler. Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of the postwar Federal Republic, also played his part in the rehabilitation of Manstein, on the grounds that West German rearmament required a sharp distinction between the Nazis and an untainted military tradition as the basis for the new Bundeswehr.

Daniel Johnson, “The moral blindness of Putin’s generals”, The Critic, 2022-05-10.

August 12, 2022

Apple, afterwards

In Quillette, Jonathan Kay looks at Apple after the death of Steve Jobs:

In 2004, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs asked famed author Walter Isaacson to write his biography. It’s a mark of Jobs’s hallowed place in the pantheon of American corporate titans that Isaacson, whose other subjects included Henry Kissinger, Benjamin Franklin, and Albert Einstein, would eventually say yes. While best-selling books about successful business leaders represent a popular niche, most specimens are fawning airport reads that combine hagiography with self-help advice for aspiring entrepreneurs. Isaacson’s Steve Jobs (2011), by contrast, was a serious work of literary non-fiction that exalted its subject as a once-in-a-generation technological savant, while also showing him to be a callous parent and scathing boss, not to mention a proponent of loopy “fruitarian” medical theories. (Much has been made of Jobs’s use of fringe therapies to treat the pancreatic cancer that killed him in 2011, but he also entertained the bizarre belief that his vegan diet allowed him to avoid bathing for days on end without developing body odour, a proposition vigorously disputed by co-workers.)

Tripp Mickle, a Wall Street Journal technology journalist who covered the Apple beat for five years, isn’t Walter Isaacson (few of us are); and, to his credit, doesn’t try to be. Nor does he seek to present his primary subjects — former lead Apple designer Jony Ive and incumbent chief executive Tim Cook — as world-changing visionaries on par with their departed boss. Indeed, the very title of his book — After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul — presents Apple as existing in a state of creative denouement since Jobs’s death — a bloated (if massively profitable) corporate bureaucracy that increasingly feeds shareholders’ demands for quarterly earnings by milking subscription services such as Apple Music and iCloud instead of developing new products.

The first five chapters of After Steve are structured as a twinned biography, following the lives of Ive and Cook from their precocious childhoods (in England and Alabama, respectively), and on through the 2010s, when the pair jointly ran Apple (in function, if not in title) following Jobs’s death.

Timothy Donald Cook grew up in Robertsdale, a farming community located roughly halfway between Mobile, Alabama and Pensacola, Florida, the middle child of a Korean War veteran and a pharmacist’s assistant. In high school, Cook was named “most studious”, and served as the business manager for the school yearbook. “In three years of math, he had never missed a homework assignment”, reports Mickle, also noting that one teacher remembers him as “efficient and dependable”. Cook also happens to be gay, a subject that caused some awkwardness for his Methodist parents, even though Cook wouldn’t come out publicly till later in life. As a means to deflect questions, Mickle reports, Cook’s mother told drug-store coworkers that her son was dating a girl in Foley, a nearby town.

Following high-school graduation, Cook went on to study industrial engineering at Auburn University and business administration at Duke. He then gravitated to the then-burgeoning field of personal computing, quickly carving out a niche within its production and supply-management back office. At IBM and Compaq, Cook turned himself into a sort of human abacus, ruthlessly bringing reduced costs, increased efficiencies, and smaller inventories to every assembly line he set eyes on. By the time he’d arrived at Apple in 1998, Mickle reports, Cook was completely neurotic about keeping any stocked materials off the books, calling inventory, “fundamentally evil”. In time, he pioneered a process by which yellow lines were painted down the floor of Apple’s production plants, with materials on the storage side of the line remaining on suppliers’ books until the very moment they were brought to the other side for assembly.

Like Ive, Cook declined to be interviewed for After Steve. And so it is entirely possible that the man has a rich inner life that remains opaque to Mickle and the outside world more generally. But the portrait that emerges in this book is one of a fanatically dedicated workaholic who rises before 4am to begin examining spreadsheets, and thinks about little else except the fortunes of Apple Inc. during the waking hours that follow. Mickle reports a sad scene in which Cook is spotted by sympathetic strangers at a fancy Utah resort, dining alone during what appears to be a solitary vacation. We also learn that Cook’s Friday-night meetings with Apple’s operations and finance staff were sometimes called “date night with Tim” by attendees, “because it would stretch for hours into the evening, when Cook seemed to have nowhere else to be.”

Canadian Army Newsreel – Allies take Sicily

canmildoc

Published 4 Sep 2011Canadian war news reel.

Testing the old saying about those who believe in nothing will believe anything

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander considers the old saying — often mis-attributed to G.K. Chesterton or C.S. Lewis:

There’s a popular saying among religious apologists:

Once people stop believing in God, the problem is not that they will believe in nothing; rather, the problem is that they will believe anything.

Big talk, although I notice that this is practically always attributed to one of GK Chesterton or CS Lewis, neither of whom actually said it. If you’re making strong claims about how everybody except you is gullible, you should at least bother to double-check the source of your quote.

Still, it’s worth examining as a hypothesis. Are the irreligious really more likely to fall prey to woo and conspiracy theories?

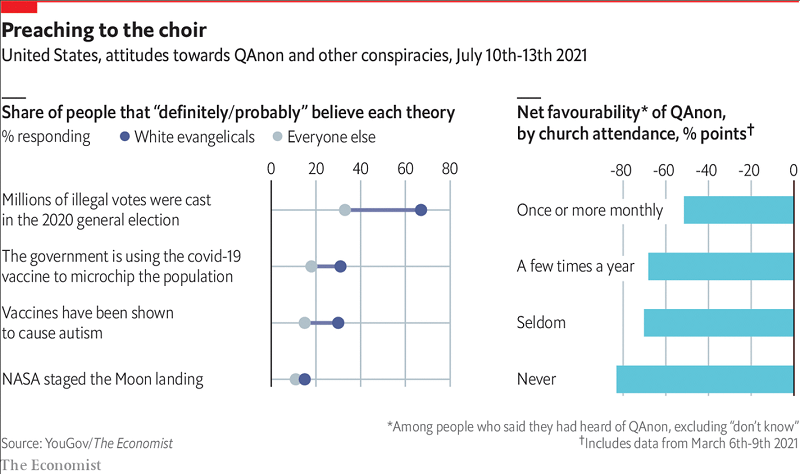

This Economist article examined the question and concluded the opposite. See especially this graph:

“White evangelicals” are more likely to believe most measured conspiracy theories, and churchgoers were more likely to believe in QAnon in particular.

There’s an obvious confounder here: the authors are doing the usual trick where they cherry-pick right-wing examples of something bad, show that more right-wingers are in favor of them, then conclude that Science Has Proven Right-Wingers Are Bad. QAnon, illegal votes, and COVID microchips are inherently right wing conspiracy theories; vaccines/autism has probably become right-coded post-COVID. Only the moon landing seems politically neutral, and it’s hard to tell if there’s a real difference on that one. So this just tells us that white evangelical church-goers are further right than other people, which we already know.

These data still deflate some more extreme claims about religion being absolutely protective against conspiracy theories. But I was interested in seeing how people of different faiths related to politically neutral conspiracies.

The 1983 “Gimli Glider” Incident

TheHistoryGuy

Published 27 Apr 2022Captain Sully’s US Airways Flight 1549 lost its engines almost immediately after takeoff, after reaching an altitude of only 2,800 feet. In 1983, a very different flight lost power at a staggering 41,000 feet, and the pilots had no choice but to try to land the plane without engines.

(more…)

QotD: Diplomatic adventures in the British Foreign Office

Lord Chalfont tells a story about his days as a Junior Minister in the Foreign Office. He attended a very grand dinner party, and spotted a lady standing alone in a long red dress. The besotted Chalfont staggered across to ask if she would waltz with him … The lady drew herself up: “I will not waltz with you for three reasons. First this is not a waltz it is the Czech national anthem. Second, you are drunk. My third and greatest objection is that I am the Cardinal Archbishop of Prague”.

Auberon Waugh, Diary, 1976-05-02 (Posted by @AuberonWaugh_PE, 2022-05-02).

August 11, 2022

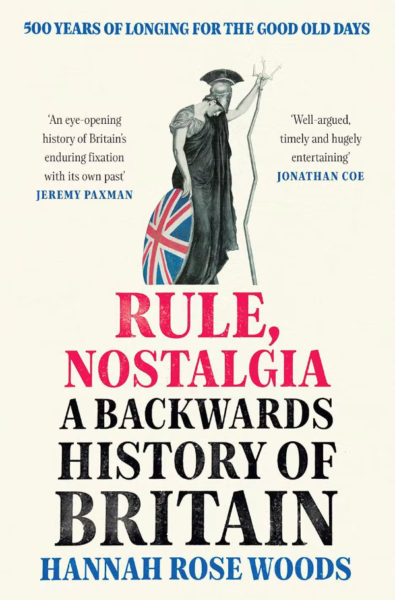

Nostalgia seen as harmful

In The Critic, Michael Ledger-Lomas reviews a new book that is critical of Britain’s chronic case of nostalgia for “the good old days”:

Indulging in pained regret for lost times might seem a harmless pleasure, but Hannah Rose Woods is here to warn it has become a pathological “fixation”. The Right, she argues, has “weaponised” nostalgia, tapping “inchoate yearnings about fading pride and glory” to fuel hatred against historians who are simply “putting the facts back in” to the national “storybook”.

Apparently, the first cure for this “peculiarly English affliction” involves refuting errors and egregious simplifications in Tory talk about the national past. Woods is an inveterate Tweeter and her Rule, Nostalgia often works like a book-length version of the “Hi, historian here” threads that infest that medium.

The Government exhorted people to get through Covid by showing the Blitz spirit, but historians know German bombing caused as much fear and resentment as pride and resolve. Britons were supposed to Keep Calm and Carry On, “but this was a fantasy”, Woods writes, because the 1940s poster with that motto never entered circulation. The tea towels lied to us.

Woods is more productive when she probes nostalgia as a cluster of emotions, rather than condemning it as a set of errors. For like all emotions, it can be usefully historicised. This insight shapes the basic structure and approach of the book, which is more ironic than irate. Our times seem to be gripped by nostalgia for the days before yesterday, but the sixties, seventies and eighties abounded with yearning for the simplicities of the Second World War.

The thirties and forties were, in turn, full of voices lamenting what one of Orwell’s heroes called the “newness of everything”, pining for the sun-dappled afternoons of Edwardian England. The Edwardians themselves lamented the lost certainties of the high Victorian age and fretted that rural tranquillity was on the wane. And so on. Woods turns the periods of our history into Russian dolls of nostalgia, each nested within the other.

It is an engaging literary device which palls as succeeding chapters ask readers to re-enact their surprise that apparently stable times were consumed with anxiety about losing touch with tradition. Woods says the “calmly elegant Georgian heyday” fretted about whether Britain should go global or remain a tight little island, while it would be a “hard sell” to claim that the age of the Reformation and the Civil War was an “age of contentment and stability”. Well, quite.

The further Woods progresses away from the “rancid Englishness” of the present, the more forgiving she becomes of nostalgia — or at least of wistful absorption in the past, which is not quite the same thing. She rightly sees that nostalgia has generally not been an obstacle to rapid social change — what bolder Victorians would have called “progress” — but has offered psychological compensation for them.

US Navy Fleet Problems – Now its time to play with carriers (VIII-XII)

Drachinifel

Published 10 Aug 2022Today we take a look at the background and thinking behind the inter-war USN Fleet Problems, with summaries of Fleet Problems 8 through 12

(more…)