Published on 31 Aug 2017

The River Thames, Key to London’s Importance as a Centre of Commerce and Government‘At Tilbury, near the mouth of the River Thames, liners from all over the world come into the landing stages, past long lines of barges and battalions of cranes. Higher up-river are the giant London docks, the busiest in the world, where the work of importing and exporting cargo us carried on unceasingly.

Westwards, up-river, are huge warehouses; cranes and smoking funnels line the banks. Approaching the City, ships pass beneath Tower Bridge, close to the imposing Tower of London. Nearby is the world of wharves and dockland offices, and directly linked to the river are London’s famous markets – Billingsgate for fish, Smithfield for meat and Covent Garden for fruit, vegetables and flowers. Here, too, is the world of finance – “the richest square mile in the world” – with the Stock Exchange, the Bank of England, and important banking and business houses known throughout the world. Further up-river is County Hall, magnificent headquarters of the London County Council; and on the left bank is the historic City of Westminster, home of the Empire’s government; lining Whitehall are big Government departments and, nearby, Westminster Abbey; and on the water’s edge, the Houses of Parliament with their elaborate and beautiful architecture. Beyond Westminster the character of the river is changed yet again, and giant Power Stations give way to residential houses, roads to gardens. Beyond Richmond, with its willow-lined banks, are the Tudor chimneys and turrets of Hampton Court; higher still is Windsor and its Castle, the home of the King.

As evening falls there is peace on the river at Windsor, but at the mouth of the Thames activity goes on into the night. There is no sleep for the greatest port in the world.’

(Films of Britain – British Council Film Department Catalogue – 1940)

September 12, 2017

The River Thames: “London River” – 1941 Educational Documentary – WDTVLIVE42

QotD: Mandatory voting is still a stupid idea

My old boss, William F. Buckley Jr., often said liberals don’t care what you do so long as it’s compulsory (though he probably borrowed the line from his friend M. Stanton Evans).

There’s probably no better illustration of this illiberal streak in liberalism than the idea of “compulsory voting.” The argument usually goes like this: Voter turnout in America is low. Low voter turnout is bad. Therefore, we should make voting mandatory. (This argument is most popular after an election like last week’s when things don’t go so well for Democrats.)

When asked why low voter turnout is bad, one usually gets a mumbled verbal stew of Norman Rockwell–esque pieties about enhanced citizenship, reduced polarization, and, on occasion, veiled suggestions that Washington would get its policies right — or I should say left — if everyone voted.

To call most of these arguments gobbledygook is a bit unfair — to gobbledygook. First note that this logic can be applied to literally every good thing, from brushing your teeth to eating broccoli. Moreover, the notion that forcing people who don’t care about politics to vote will make them more engaged and thoughtful citizens is ludicrous. We force juvenile delinquents (now called “justice-involved youth” by the Obama administration) and other petty criminals to clean up trash in parks and alongside highways. Is there any evidence this has made them more sincere environmentalists? If we gave every student in the country straight As, that would make all the education trend lines look prettier, but it wouldn’t actually improve education.

This sort of enforced egalitarianism is reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s short story “Harrison Bergeron,” set in a society where everyone must be equal. Above-average athletes are hobbled to make them conform with the unathletic. The smart are made dumb. Ballet dancers are weighed down so they can’t jump any higher than normal people. The prettier ones must wear masks.

[…]

Even the ancient left-wing assumption that if we could politically activate the downtrodden masses of the poor and the oppressed to storm the polling stations, we might topple the supposed tyranny of privilege and inequality is wrong, too. The overwhelming consensus among political scientists who’ve looked at the question is that universal turnout would not change the results of national elections. It would, however, probably have a positive effect on local elections for school boards and municipal governments, because these low-turnout elections are monopolized by entrenched bureaucrats and government unions (and that’s the way they like it, by the way).

Jonah Goldberg, “Progressives Think That Mandatory Voting Would Help Them at the Polls”, National Review, 2015-11-13.

September 11, 2017

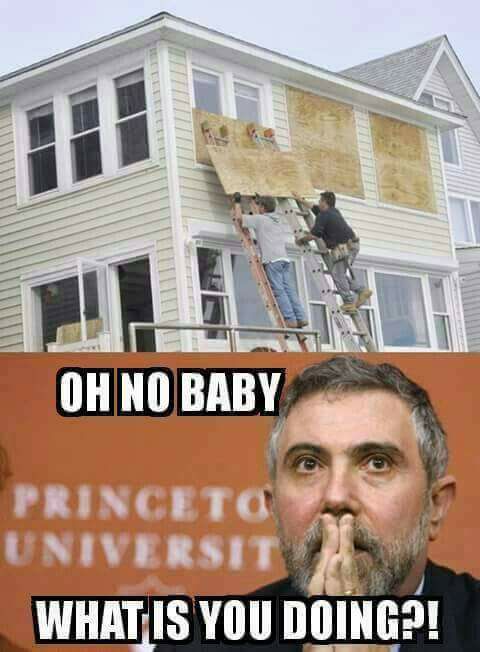

Harvey, Irma, and Frédéric – the “Broken Window Fallacy” returns

Jon Gabriel tries to set the record straight on what a natural disaster means for the economy (hint, ignore anyone who says the GDP will rise due to the recovery efforts):

Ever since Hurricane Harvey slammed into Texas two weeks ago, we’ve seen countless images of heroic rescues, flooded interstates and damaged buildings.

As awful as the human toll was, it was not as bad as many of us feared. But it will take months to repair the homes, businesses and infrastructure of Houston and the surrounding area. The same will be true in Florida after Hurricane Irma.

The economic impact could be felt for years, but many economists and financial experts think there’s a silver lining.

The Los Angeles Times crowed that Harvey’s destruction is expected to boost auto sales. CNBC reported that Harvey “could be a slight negative for U.S. growth in the third quarter, but economists say it may ultimately provide a tiny boost to the national economy because of the rebuilding in the Houston area.”

Even Goldman Sachs is looking at the bright side, noting that there could be an increase in economic activity, “reflecting a boost from rebuilding efforts and a catchup in economic activity displaced during the hurricane.”

Economically speaking, it’s great news that all this damage in Texas and Florida needs to be fixed, right? Not only does this mean big bucks for cleanup crews, but think of all the money that street sweepers, construction workers and Home Depots will rake in.

And what about all those windows broken by the high winds? This will be the Golden Age of Texas Glaziery!

Not so fast.

All of this is based on a misunderstanding of what the GDP actually measures. It’s a statistic that often gets mentioned in the newspapers and on TV, but it is almost always used in a way that misleads people about what is happening in the economy. GDP — Gross Domestic Product — is intended to show the approximate total of goods and services produced in a national economy. Thus, when the GDP goes up, it means that the current period being measured recorded more goods and services produced than in the previous period.

When a natural disaster like a hurricane, earthquake, flood, or tornado strikes a city, state or region, all the work required to fix the damage will artificially boost the recorded GDP for that year. But the affected area isn’t that much richer than it was before, despite the GDP going up, because the GDP does not measure the losses suffered during the natural disaster.

This is where Frédéric comes in. I’m referring to the French economist and author Frédéric Bastiat, who brilliantly illustrated the GDP misunderstanding in his essay “What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen“:

In the economic sphere an act, a habit, an institution, a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently; they are not seen; we are fortunate if we foresee them.

There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.

Yet this difference is tremendous; for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. Whence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good that will be followed by a great evil to come, while the good economist pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present evil.

The GDP problem I identified at the start of this post is a general case of what Bastiat called the “Broken Window Fallacy”:

Have you ever been witness to the fury of that solid citizen, James Goodfellow, when his incorrigible son has happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at this spectacle, certainly you must also have observed that the onlookers, even if there are as many as thirty of them, seem with one accord to offer the unfortunate owner the selfsame consolation: “It’s an ill wind that blows nobody some good. Such accidents keep industry going. Everybody has to make a living. What would become of the glaziers if no one ever broke a window?”

Now, this formula of condolence contains a whole theory that it is a good idea for us to expose, flagrante delicto, in this very simple case, since it is exactly the same as that which, unfortunately, underlies most of our economic institutions.

Suppose that it will cost six francs to repair the damage. If you mean that the accident gives six francs’ worth of encouragement to the aforesaid industry, I agree. I do not contest it in any way; your reasoning is correct. The glazier will come, do his job, receive six francs, congratulate himself, and bless in his heart the careless child. That is what is seen.

But if, by way of deduction, you conclude, as happens only too often, that it is good to break windows, that it helps to circulate money, that it results in encouraging industry in general, I am obliged to cry out: That will never do! Your theory stops at what is seen. It does not take account of what is not seen.

It is not seen that, since our citizen has spent six francs for one thing, he will not be able to spend them for another. It is not seen that if he had not had a windowpane to replace, he would have replaced, for example, his worn-out shoes or added another book to his library. In brief, he would have put his six francs to some use or other for which he will not now have them.

Let us next consider industry in general. The window having been broken, the glass industry gets six francs’ worth of encouragement; that is what is seen.

If the window had not been broken, the shoe industry (or some other) would have received six francs’ worth of encouragement; that is what is not seen.

And if we were to take into consideration what is not seen, because it is a negative factor, as well as what is seen, because it is a positive factor, we should understand that there is no benefit to industry in general or to national employment as a whole, whether windows are broken or not broken.

Now let us consider James Goodfellow.

On the first hypothesis, that of the broken window, he spends six francs and has, neither more nor less than before, the enjoyment of one window.

On the second, that in which the accident did not happen, he would have spent six francs for new shoes and would have had the enjoyment of a pair of shoes as well as of a window.

Now, if James Goodfellow is part of society, we must conclude that society, considering its labors and its enjoyments, has lost the value of the broken window.

From which, by generalizing, we arrive at this unexpected conclusion: “Society loses the value of objects unnecessarily destroyed,” and at this aphorism, which will make the hair of the protectionists stand on end: “To break, to destroy, to dissipate is not to encourage national employment,” or more briefly: “Destruction is not profitable.”

Related: Shared by Thomas Forsyth on Facebook:

Smug Canadian vanity over helping (some) refugees may harm a larger number of more desperate refugees

Jonathan Kay in the National Post:

By my anecdotal observation, these accounts are not overblown. At Toronto dinner parties, it’s become common for upscale couples to brag about how well their sponsored refugees are doing. (Houmam has a job! The kids already speak English! Zeinah bakes the most amazing Syrian pastries — I’m going to serve some for desert!) Syrian refugees aren’t just another group of Canadian newcomers. They’ve become central characters in the creation of our modern national identity as the humane yang to Trump’s beastly yin.

Given all this, it seems strange to entertain the thought that — contrary to this core nationalist narrative — our refugee policy may actually be doing more harm than good. Yet after reading Refuge: Rethinking Refugee Policy in a Changing World, a newly published book jointly authored by Paul Collier and Alexander Betts, I found that conclusion hard to avoid. When it comes to helping victims of Syria’s civil war, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

[…]

What’s worse, the lottery-style nature of the system means that refugees have incentive to take enormous risks. German Chancellor Angela Merkel received lavish praise for admitting more than 1 million Muslim refugees in 2015. But the data cited in Refuge suggest the tantalizing prospect of first-world residency is precisely what motivated so many refugees to endanger their lives by setting out from Turkey in tiny watercraft. We like to believe that generous refugee-admission policies are an antidote to the perils that claimed Alan Kurdi’s life. The exact opposite seems more likely to be true.

Moreover, the refugees who make it to the West do not comprise a representative cross-section of displaced Syrians — because those who can afford to pay off human smugglers tend to be the richest and most well-educated members of their society. (Betts and Collier cite the stunning statistic that fully half of all Syrian university graduates now live outside the country’s borders.) This has important policy ramifications, because refugees who remain in the geographical vicinity of their country of origin typically return home once a conflict ends — whereas those who migrate across oceans usually never come back. Insofar as the sum of humanity’s needs are concerned, where is the need for Syrian doctors, dentists and nurses more acute — Alberta or Aleppo?

[…]

But logically sound as it may be, the authors’ argument also flies in the face of our national moral vanity. Scenes of refugees being greeted at the airport by our PM offer a powerful symbol of our humanitarian spirit. Having our PM cut cheques to foreign aid agencies? Less so. While focusing more on supporting Syrian refugees who’ve been displaced to other Middle Eastern countries would allow us to do more good with the same amount of money, we’d also be acting in a less intimate and personal way — and we’d get fewer of those heartwarming newspaper features about Arab children watching their first Canadian snowstorm.

And so we have to ask ourselves: In the end, what’s more important — doing good, or the appearance of doing good? If we’re as pure of heart as we like to imagine, we’ll seek out the policy that saves the most people, full stop. And Refuge supplies an outstanding road map for getting us there.

5 Woodworking Cuts You Need to Know How to Make | WOODWORKING BASICS

Published on 9 Jun 2017

Sometimes the terminology gets confusing, so in this BASICS episode, I’ll break down the 5 basic types of woodworking cuts and how to make them.

QotD: Does inequality matter?

The central problem with the book, however, is an ethical one. Piketty does not reflect on why inequality by itself would be bad. To be sure, it’s irritating that a super rich woman buys a $40,000 watch. The purchase is ethically objectionable. She should be giving her income in excess of an ample level of 2 cars, say, not 20; 2 houses, not 7; 1 yacht, not 5 — to effective charities. Andrew Carnegie enunciated in 1889 the principle that “a man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.” Carnegie gave away his entire fortune. (Well, he gave it at death, after enjoying a castle in his native Scotland and a few other baubles.) But the fact that many rich people act in a disgraceful fashion does not automatically imply that the government should intervene to stop it. People act disgracefully in all sorts of ways. If our rulers were assigned the task in a fallen world of keeping us all wholly ethical, the government would bring all our lives under its fatherly tutelage, a nightmare achieved approximately before 1989 in East Germany and now in North Korea.

Notice that in Piketty’s tale the rest of us fall only relatively behind the ravenous capitalists. The focus on relative wealth or income or consumption is one serious problem in the book. Piketty’s vision of apocalypse leaves room for the rest of us to do very well indeed — rather non-apocalyptically — as in fact since 1800 we have. What is worrying Piketty is that the rich might possibly get richer, even though the poor get richer, too. His worry is purely about difference, about a vague feeling of envy raised to a theoretical and ethical proposition.

But our real concern should be with raising up the poor to a condition of dignity, a level at which they can function in a democratic society and lead full lives. It doesn’t matter ethically whether the poor have the same number of diamond bracelets and Porsche automobiles as do owners of hedge funds. But it does indeed matter whether they have the same opportunities to vote or to learn to read or to have a roof over their heads.

Adam Smith once described the Scottish idea as “allowing every man to pursue his own interest his own way, upon the liberal plan of equality, liberty and justice.” It would be a good thing, of course, if a free and rich society following Smithian liberalism produced a Pikettyan equality. In fact, it largely has, by the only ethically relevant standard of basic human rights and basic comforts. Introducing liberalism in Hong Kong and Norway and France, for instance, has regularly led to an astounding betterment and to a real equality of outcome — with the poor acquiring automobiles and hot-and-cold water at the tap that were denied in earlier times even to the rich, and acquiring political rights and social dignity that were denied in earlier times to everyone except the rich.

Deirdre N. McCloskey, “How Piketty Misses the Point”, Cato Policy Report, 2015-07.

September 10, 2017

British Malaya – US Equipment – Boobytraps I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 9 Sep 2017

It’s time for another exciting episode of Out Of The Trenches again, this episode talks about British Malaya in WW1, the French and British equipment the US troops used and traps.

Special Air Service (SAS) – The Falklands Campaign

Published on 13 Jul 2016

Special Air Service (SAS) – The Falklands Conflict

When Argentina invaded the Falklands in April, 1982, Britain dispatched a large Naval Task Force to recapture the Falklands. Steaming south with the British fleet were D and G Squadron of the SAS, with supporting signals units.

In search of silphium, the lost herb of the Roman empire

Zaria Gorvett recounts the story of a Roman-era herb that was at one point literally worth its weight in gold:

Long ago, in the ancient city of Cyrene, there was a herb called silphium. It didn’t look like much – with stout roots, stumpy leaves and bunches of small yellow flowers – but it oozed with an odiferous sap that was so delicious and useful, the plant was eventually worth its weight in gold.

To list its uses would be an endless task. Its crunchable stalks were roasted, sauteed or boiled and eaten as a vegetable. Its roots were eaten fresh, dipped in vinegar. It was an excellent preservative for lentils and when it was fed to sheep, their flesh became delectably tender.

Perfume was coaxed from its delicate blooms, while its sap was dried and grated liberally over dishes from brains to braised flamingo. Known as “laser”, the condiment was as fundamental to Roman haute cuisine as eating your food horizontally in a toga.

[…]

Indeed, the Romans loved it so much, they referenced their darling herb in poems and songs, and wrote it into great works of literature. For centuries, local kings held a monopoly on the plant, which made the city of Cyrene, at modern Shahhat, Libya, the richest in Africa. Before they gave it away to the Romans, the Greek inhabitants even put it on their money. Julius Caesar went so far as to store a cache (1,500lbs or 680kg) in the official treasury.A coin of Cyrene depicting the stalk of a Silphium plant. (Source: 1889 edition of Principal Coins of the Ancients, plate 35, via Wikimedia)

But today, silphium has vanished – possibly just from the region, possibly from our planet altogether. Pliny wrote that within his lifetime, only a single stalk was discovered. It was plucked and sent to the emperor Nero as a curiosity sometime around 54-68AD.

With just a handful of stylised images and the accounts of ancient naturalists to go on, the true identity of the Romans’ favourite herb is a mystery. Some think it was driven to extinction, others that it’s still hiding in plain sight as a Mediterranean weed. How did this happen? And could we bring it back?

Barbarossa: Why such high Soviet Losses? – Explained

Published on 20 Jun 2017

The Red Army suffered heavy losses during Operation Barbarossa, but it also inflicted heavy losses on the Wehrmacht. This means it was not just some helpless giant, but it also begs the questions, why were the losses so high? This video discusses several factors and refers heavily to current academic research namely from Alexander Hill and David Stahel.

Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.

QotD: Peak oil

Witness, brothers and sisters, witness. The oil, it’s going to run out. Peak production of the world’s oilfields has either passed or is about to pass; from here on out it’s rising oil prices forever. Now we wave our hands and pronounce that the energy-guzzling capitalist West (and especially Amerikka) is so addicted to cheap oil that its decadent empire will collapse, collapse I tell you. Barely concealed gloating follows.

There are so many mutually-reinforcing idiocies here that it’s hard to know where to start. As I was thinking of writing about this, one of my commenters pointed out that above $32 per barrel it becomes economical to build Fischer-Tropf plants and make your oil out of coal. This is old tech; the Germans did it during WWI. At slightly higher price points, MHD generators to burn garbage start to look good.

These are instances of a more general phenomenon: markets adapt to price shifts! To wreck an economy with oil-price rises, they’d have to spike so fast and so far that you somehow couldn’t run the cement trucks to build the Fischer-Tropf plants. Not gonna happen.

In fact, the long-term trend will be that the amount of oil invested per constant-dollar value of goods produced in the U.S. economy drops faster than the price of oil rises. This is a safe prediction not because manufacturers have all bought into Green ideology but because they want to make money. This means that they have a market incentive to use their inputs (including oil) a efficiently as possible, and to substitute less expensive inputs for more expensive ones. It’s called capitalism, and it works.

(And, by the way, the cheapest input of all is information. Buckminster Fuller pointed out forty years ago that as technologies mature, the products tend to get smaller and lighter and less energy-intensive and smarter. Your cellphone today weighs less than it used to, and costs less oil to produces than it used to, because its design is smarter. Information has replaced mass. This trend will continue and accelerate.)

The peak-oil collapse scenario is not credible for five minutes to anybody who understands market economics. But the sort of people who believe it are blinded by their own prejudices; fundamentally they think market economics is an invention of the Devil. They need to believe in the collapse, because they need to believe that the wickedness of Americans and capitalists and Republicans will be punished.

Eric S. Raymond, “Peak Oil — A Wish-Fulfillment Fantasy for Secular Idiots”, Armed and Dangerous, 2005-11-13.

September 9, 2017

Dr. Jerry Pournelle, 1933-2017

I saw this brief notice at Instapundit last night and shared it with my Facebook friends:

ALEX POURNELLE TEXTS:

Hi

I’m afraid that Jerry passed away

We had a great time at DragonCon

He did not suffer. Please feel free to post this news.Rest in peace, Jerry. You will be missed.

I met Dr. Pournelle at SF conventions a couple of times, but you can’t say you knew someone on the basis of fleeting contacts like that. We did have a few minutes of discussion at one convention on the topic of why Harrison Ford’s portrayal of Indiana Jones was/was not a faithful characterization of how most people viewed archaeologists … which was highly entertaining. Although I enjoyed his SF writing, I actually thought of him more as a computer journalist, as I was a huge fan of his Chaos Manor columns in Byte magazine. As with George Orwell’s “As I please” columns, Pournelle didn’t let himself be limited to just bits and bytes and the range of topics was sometimes far outside the normal range for the magazine.

Here is his Wikipedia page.

Minimum Wage: Bad for Humans, Good for Robots

Published on 7 Sep 2017

Jacking up the minimum wage sounds like a good idea, but it comes with disastrous consequences: low-skilled workers getting canned, employers cutting hours, and, of course, robots.

The rise of the “I would like to acknowledge that…” announcement in Canada

In The New Yorker, Stephen Marche discusses “Canada’s Impossible Acknowledgement”:

Every morning, at the start of the school day in Toronto, my children hear the following inelegant little paragraph read aloud, just before the singing of “O Canada”:

I would like to acknowledge that this school is situated upon traditional territories. The territories include the Wendat, Anishinabek Nation, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nations, and the Métis Nation. The treaty that was signed for this particular parcel of land is collectively referred to as the Toronto Purchase and applies to lands east of Brown’s Line to Woodbine Avenue and north towards Newmarket. I also recognize the enduring presence of Aboriginal peoples on this land.

I hear the same little speech, or a version of it, at gala events — literary prizes, political fund-raisers, that sort of thing — when whichever government representative happens to be there reads some kind of acknowledgment before his or her introductory remarks. But you know a phenomenon has really arrived in Canada when it involves hockey. Both the Winnipeg Jets and the Edmonton Oilers began acknowledging traditional lands in their announcements before all home games last season. Acknowledgment is beginning to emerge as a kind of accidental pledge of allegiance for Canada — a statement made before any undertaking with a national purpose.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released its final report, with ninety-four calls to action, and Justin Trudeau was elected to great gusts of hope that we might finally confront the horror of our history. In the time since, the process of reconciliation between Canada and its First Nations has stalled, repeating the cycles of overpromising and underdelivering that have marred their relationship from the beginning. The much-vaunted commitment to “Nation to Nation” negotiation has been summarily abandoned. The National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls — another Trudeau election promise — has been plagued by resignations, inertia, and accusations of general ineffectiveness. Nonetheless, the acknowledgment is spreading. No level of government has mandated the practice; it is spreading of its own accord.

It’s not nothing … but from the point of view of many First Nations activists, it might as well be nothing. It also involves awkward moments when the speaker doesn’t quite get the acknowledgement acceptably “correct”:

In other places, particularly in the bigger cities, the acknowledgment can become exponentially more difficult. The British Crown acquired Toronto, or, rather, the 250,880 acres that include present-day Toronto, from the Mississaugas, in 1787, for two thousand gun flints, two dozen brass kettles, ten dozen mirrors, two dozen laced hats, a bale of flannel, and ninety-six gallons of rum. The British government officially purchased the land for an additional ten shillings, in 1805. But even before the Toronto Purchase, as it was called, the land was a contested site between indigenous peoples. That history is also reflected in the question of who should be named in the acknowledgment. “For the sake of current land claims and also for the sake of basic respect, you have to name them, and you have to be correct about it,” Jesse Thistle, a historian at York University in Toronto, says. “Haudenosaunee people, some of them, don’t want to recognize that the Anishnabe took control and were here historically. Some Anishnabe people will not recognize that the Haudenosaunee people were here. And both those people sometimes want to erase the Wendat.” Historical truth is always subject to the structures of power. Always. The erasure of the Wendat “is, in a way, a kind of indigenous way of doing what the British were doing, in terms of writing other people out of the narrative,” Thistle says.

But writing marginalized peoples into the narrative is not always the correct instinct, either. Thistle, who is himself Métis-Cree, believes that the Métis should not be included in the list of traditional land acknowledgments in Toronto; he has brought his concerns to the authorities at the Toronto District School Board as well. There were Métis in Toronto — they constituted a “historical presence” — but it was not a homeland, and to claim otherwise, for Thistle, “disempowers the Haudenosaunee or the Anishnabe, who do have a rightful claim.”

The Seven Years’ War

Published on 19 Nov 2016

The Seven Years’ War essentially comprised two struggles. One centered on the maritime and colonial conflict between Britain and its Bourbon enemies, France and Spain; the second, on the conflict between Frederick II (the Great) of Prussia and his opponents: Austria, France, Russia, and Sweden. Two other less prominent struggles were also worthy of note. As an ally of Frederick, George II of Britain, as elector of Hanover, resisted French attacks in Germany, initially only with Hanoverian and Hessian troops but from 1758 with the assistance of British forces also. In 1762, Spain, with French support, attacked Britain’s ally Portugal, but, after initial checks, the Portuguese, thanks to British assistance, managed to resist successfully.