Chris Bray has more disturbing details drawn from Tim Reiterman’s history/biography of Reverend Jim Jones and the Peoples Temple, Raven:

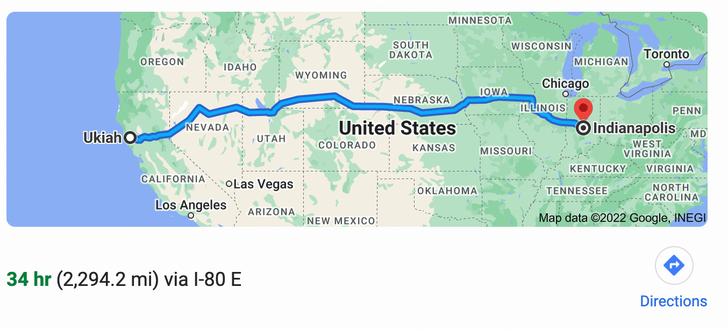

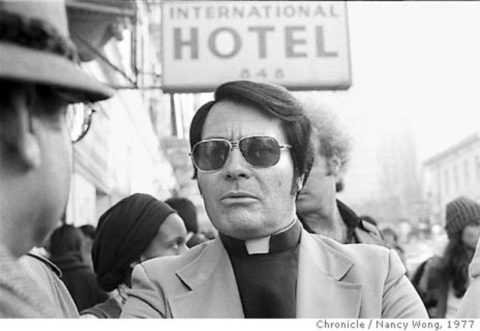

Reverend Jim Jones in front of the International Hotel in San Francisco’s Chinatown on Kearny & Jackson Streets during a rally to save the hotel.

San Francisco Chronicle photo by Nancy Wong, 1977 via Wikimedia Commons.

He broke families, he taught fear, he isolated people, he shamed and demeaned people to break their spirit, he made people dependent, he ran obedience tests with deliberate sadism to see who would take it. That’s it. Those are the tools. Again, all of this comes from Tim Reiterman’s book Raven, which I encourage you to read.

When Jonestown shows up in news stories, Peoples Temple is usually described as a 1970s-era Bay Area cult that moved to Guyana. But that’s not where Jim Jones started the church — he began in Indianapolis in the 1950s. In a moment when there were mostly black churches and white churches, Jones insisted on building a racially integrated congregation. Then he warned them, with increasing urgency, that the church would be attacked by white supremacists who were outraged by their social progress; a flood of menacing phone calls and threatening letters backed up the point. One night, as members of the church visited Jones at home, he stepped into his bedroom alone — just as a brick crashed through the window. The visitors rushed into the bedroom, where Jones told them that the white supremacists had just attacked his house. (Miraculously, the brick and the broken glass had landed outside the window.)

Over the years, the threats built to a crescendo — look, another terrifying letter! — and Jones warned his congregation that the white supremacist threat was moving toward its culmination. At the same time, he began to receive visions about the other great threat hanging over the world: nuclear war. It’s coming, he told them, over and over again, sometimes even naming likely dates for the attack.

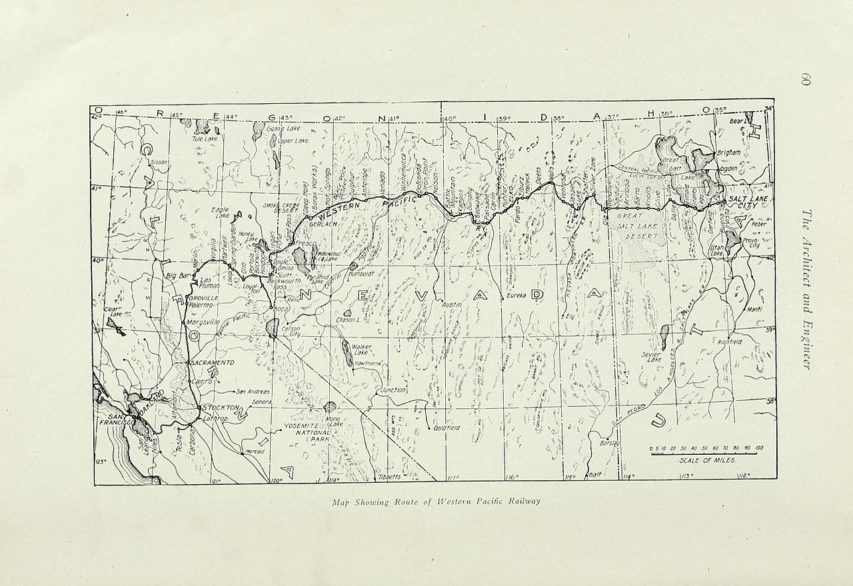

Finally, under the increasingly terrifying dual threat of death from local attack or death from Soviet missiles, either of which could happen at any moment, Jones sent an advance party across the country to find a place where his people could survive — and then, with a secure haven located, he led his congregation to safety in a remote area of Northern California. Good thing they made it out, right?

For a congregation of Midwesterners, the journey to California meant a departure from parents, siblings, and adult children; for many, it meant a departure from their birthplace and every social connection they had made outside the church. It put them in the woods a couple thousand miles from their families, in isolation together in a new place.

Then, with church members living in church-built homes on a church-owned property, Jones helped them to see that selfishness was cruel and atavistic. People who loved, who were spiritual, shared together. So what kind of self-involved monster kept a husband or a wife trapped in a limiting one-on-one relationship? Liberating the members of his church, he helped them to start having sex with other church members outside of their marriages. In some instances, particularly close couples with especially stable relationships — like the church attorney Tim Stoen and his wife, Grace — forced Jones to issue direct orders telling them who else they would be having sex with. And yes, it did liberate them from the confinement of their close marriage, quickly and decisively.

Jones also helped by having sex with everybody, teaching them how to become free. One night, Jones had a heart attack — another maneuver he used all the time — in the presence of a church member named Larry Layton; as Layton rushed to help, Jones explained that he needed to fuck Layton’s wife, and had already started, and had brought her to orgasm “no fewer than sixteen or seventeen times” during their first encounter. But no worries, because Jones also assigned another church member, Karen Tow, to have sex with Layton to assuage his pain. After the divorce, Layton and Tow got married — but Tow let Layton know that she still preferred to have sex with Jones. See how liberating this is?