Forgotten Weapons

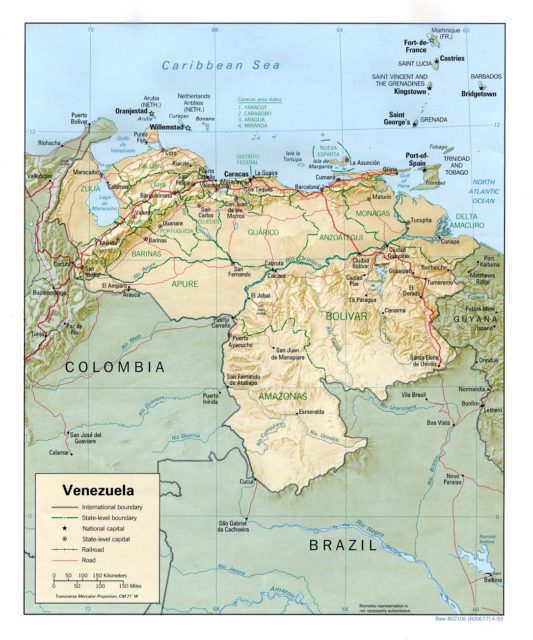

Published Dec 1, 2023Venezuela was the first nation to purchase the FN-49 rifle, before even the Belgian military. In fact, the Venezuelan contract was signed in 1948, before the “FN-49” designation was even in place. Venezuela bought a total of 8,012 rifles in two batches — 4,000 rifles plus 12 cutaway training examples delivered in 1949 and a further 4,000 more rifles delivered in June 1951. All of them included the integral muzzle brake and scope mounting cuts, although no scopes were ever procured. They were all semiautomatic models.

Some of the rifles were issued and used, but some appear to have remained in depots their entire life. Venezuela was also an early adopter of the FAL, and the FN-49 was only used for a short time. In 1966, all of them (or virtually all) were sold as surplus to InterArms, and brought onto the US collector market.

(more…)

March 6, 2024

Venezuelan FN49: The First FN49 Contract

December 9, 2023

November 5, 2023

September 21, 2022

Pierre Poilievre’s (very modern) modern family

In The Line, Rahim Mohamed discusses how the Poilievre family makes it difficult for Liberal propagandists to portray Poilievre as some sort of ultra-nationalist white supremacist (as they clearly would if they could):

Pierre and Ana Poilievre at a Conservative leadership rally, 21 April, 2022.

Photo by Wikipageedittor099 via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a critical moment for any new party leader. Poilievre need only look at his most immediate predecessor, Erin O’Toole, for an example of how quickly it can go wrong. After tacking to the right of rival Peter MacKay to win the party’s 2020 leadership race, O’Toole pivoted sharply to the centre once Conservative party leader, courting labour unions, calling himself a “progressive conservative” and backtracking on a promise to protect the conscience rights of pro-life doctors and nurses. O’Toole’s “authenticity problem” remained a storyline throughout his rocky tenure at the helm of the Conservative party.

Poilievre executed, successfully, an uncommonly combative and partisan frontrunner campaign, making any notion of a centrist pivot a total non-starter. He has tacked even further to the right than O’Toole did as a leadership candidate: branding moderate rival Jean Charest “a Liberal”, sparring with Leslyn Lewis over who supported this winter’s convoy protests first, leading “defund the CBC” chants at his rallies; and, perhaps most brazenly, promising to bar federal ministers from attending the World Economic Forum (a bête noire of far-right conspiracy theorists).

So how will Poilievre (re-)introduce himself to Canadian voters? If his first week as Conservative party leader is any indication, his telegenic, multicultural and decidedly “modern” family will be central to his efforts to cast himself in a softer, more prime ministerial light.

After the results of the leadership vote were announced, the first person to address Conservative party members was not the party’s new leader himself, but his Venezuelan-born wife Ana. Ana Poilievre (née Anaida Galindo) delivered a confident and well-received set of introductory remarks, cycling effortlessly between English, French and Spanish throughout the five-minute-long address.

The most effective moments of Ana Poilievre’s speech centred on her family’s hardscrabble journey from a comfortable middle-class existence in pre-Chavez Venezuela to precariously living paycheque-to-paycheque in the East End of Montreal. “My father went from wearing business suits and managing a bank to jumping on the back of a truck to collect fruits and vegetables,” she reminisced with her family in attendance; adding, “there is no greater dignity than to provide for your own family” to one of the loudest rounds of applause of the evening. These words captured the Galindo family’s distinct immigrant story, yet undoubtedly resonated with thousands of immigrants and first-generation Canadians across the country. (My own parents, for what it’s worth, were forced to start from scratch after being exiled from their birth country of Uganda as young adults.)

Pierre Poilievre returned to this theme in the victory speech that followed: “my wife’s family not only raised this incredible woman, but they came to this country … with almost nothing; and they have since started businesses, raised kids, served in the military, and like so many immigrant families, built our country.” He went on to thank members of his own family, including his (adoptive) father’s same-sex partner Ross and his biological mother Jackie (who gave Poilievre up for adoption after having him as a teenager). “We’re a complicated and mixed-up bunch … like our country,” he later joked.

All kidding aside, no major federal party leader has ever had a family that looks more like Canada. Members of Poilievre’s extended family span multiple nationalities and speak English, French and Spanish as first languages. He has a South American wife, an adoptive father who is in a relationship with another man, and a biological mother who’s young enough to be his sister — Pierre Poilievre is basically a character from the hit sitcom Modern Family. The governing Liberals, who have made identity politics central to their party brand and spent the past seven months trying to connect Poilievre to white supremacism, should be worried.

August 28, 2020

March 4, 2020

QotD: Tax cuts “for the rich”

I keep hearing about how tax cuts are “giveaways” for the rich. Never mind that some rich people will see their taxes go up. This is philosophically grotesque. The people saying it may be more civilized and restrained than the pro-government mobs in the streets of Caracas, but it’s still basically the same idea: “The People” or “the nation” own everything. The state is the expression of the peoples’ spirit or of the nation’s “will”, and therefore it effectively owns everything. Thus, taking less money from you is the same as giving you more money.

This is why populism and nationalism, taken to their natural conclusions, always lead to statism. The state is the only expression of the national or popular will that encompasses everybody. So, the more you talk about how the fundamental unit of society is a mythologized collective called “The People” or the nation, the more you are rhetorically empowering the state.

Sure, the Constitution begins with the words “We the People,” but that is not a populist sentiment — it’s a statement of precedence in terms of authority: The people come before the government (not the European notion of the state). The spirit of the Constitution is entirely about the fact that The People are not all one thing. It places the rights of a single person above those of the entire federal government! It assumes not only that the people will disagree among themselves, but that the country will be better off if there is such disagreement. No populist frets about the tyranny of the majority. American patriots do.

But if you recognize that humans create wealth with their brains and their industry and that it therefore belongs to them, you’ll be a little more humble about the state’s “right” to take as much as it wants to spend how it wants. Human ingenuity is the engine of wealth creation, and there is no other.

But that doesn’t mean government doesn’t play a role. Because, as I said, there will be no wealth creation if there is no rule of law. There will be no investment or ingenuity if there is no guarantee that you will be able to collect on that investment or reap the benefits of your innovation. Without such an environment, the biggest mob wins. And when the mob wins, children starve to death in what should be one of the richest countries in the world.

Jonah Goldberg, “America and the ‘Original Position'”, National Review, 2017-12-22.

January 22, 2020

QotD: National “wealth”

All the wealth we’ve accumulated is ultimately between our ears.

While working on my book, I read all these different accounts of where capitalism comes from. I was amazed by how many of them start from the assumption that wealth is … stuff. Depending on which Marxist you’re talking to, capitalism is the ill-gotten-booty of the Industrial Revolution, slavery, imperialism, and the rest. I don’t want to get into all of that here — there will be plenty of time when the book comes out.

But all of these assumptions are based on the idea that having stuff makes you rich. Now, in fairness, that’s true for individuals. But it doesn’t really work that way for societies. Writing about Venezuela earlier this week is what got this in my head. Venezuela is poor and getting poorer by the minute: Babies are dying from starvation.

Meanwhile, Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. According to lots of people, not just Marxists, this should make no sense. Oil is valuable. If you have more of it than anyone else, you should be able to make money. For a decade, the American Left loved Hugo Chávez and then Nicolás Maduro because they allegedly redistributed all of the country’s wealth from the rich to the poor. These dictators were using The Peoples’ resources for the common good. Blah blah blah.

It turns out that the greatest resource a country has is its institutions. In economics, an institution is just a rule, which is why the rule of law in general and property rights in particular are the most important institutions there are, with the exception of the family. Take away the rule of law in any country, anywhere and that country will get very poor, very fast. Stop protecting the fruits of someone’s labor, enforcing legal contracts, guarding against theft from the state or the mob (a distinction without a difference in Venezuela’s case) and wealth starts to evaporate.

But even that is too complicated. Oil is worthless on its own. If you went back in time to the Arabian Peninsula before oil became a valuable commodity, you wouldn’t look at the squabbling nomads and call them rich, even though they were playing polo with a goat’s head above billions of barrels of oil. Go get lost in the Amazon by yourself. What would you rather have, a map or big-ass diamond? The diamond only has value once you get out of the jungle, but you can’t get out without the map.

Jonah Goldberg, “America and the ‘Original Position'”, National Review, 2017-12-22.

September 30, 2019

QotD: Oil price volatility

Why is the price of oil so volatile? I thought I knew the answer — scarcity and OPEC — till I read Aguilera and Radetzki. They make the case that depletion has never been much of a factor in driving oil prices, despite the obvious drying up of certain fields (such as the North Sea today). Nor did OPEC’s interventions to fix prices make much difference over the long run. What caused the price of oil to rise much faster than other commodities, though erratically and with crashes, they argue, was the result of one factor in particular.

There was a wave of nationalisation in the oil industry beginning in the 1960s. Today some 90 per cent of oil reserves are held by nationalised companies. ExxonMobil and BP are minnows compared with the whales owned by the governments of Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Nigeria and Russia. Post-colonial nationalisation affected many resource-based industries, but whereas many mineral and metal companies were privatised in the 1990s as their grotesque inefficiencies became visible, the same has not happened to state oil companies.

The consequence is that most oil is produced by companies that are milked by politicians, and consequently starved of cash (or incentives) for innovation and productivity. Lamenting “politicians’ extraordinary ability to mess things up”, the two authors note “the severely destructive role that can be played by political fights over the oil rent and its use”.

If politicians don’t get in the way, and we have two decades of relatively cheap oil it will be bad news for petro-dictators, oil-igarchs, ISIS thugs, and the promoters of wind power, solar power, nuclear energy and electric cars. But it is good news for everybody else, especially those on modest incomes.

Matt Ridley, “Low oil prices are a good thing”, The Rational Optimist, 2016-02-14.

June 28, 2019

August 22, 2018

August 4, 2018

QotD: Supply and demand

… that terribly simplistic stuff about supply and demand in those econ 101 classes is actually true. Prices are not some arbitrary numbers thrown at something by the capitalist neoliberals in order to do down the proletariat. They’re vital and essential information about who wants what and who is willing to produce what. Where the supply and demand curves meet is where the market will clear and the market price will be the market clearing price. The meaning of this is that when you decide to arbitrarily throw a price at something you’re going to up set that balance. And if you tell producers that the price will be lower than the market one then they will produce less. And as demand curves slope downwards so will consumers desire more at that lower price. Thus price fixing below the market price produces a shortage, a dearth.

This is not some optional feature, it’s an essential fact about our universe. It is the explanation for those food shortages that Venezuela has been having. More than that it’s the only explanation we need or desire. Fix prices below the market price and you will have shortages. Stop fixing prices and you will stop having shortages.

So, well done to Venezuela for giving in to reality there. And this is something that we need to take on board too. Rent controls which fix the price of housing below the market price will lead to a shortage of housing. And the opposite applies too – fix the price of labour above that market price with a minimum wage and you’ll have an excess supply of labour. Or, as we usually call that, an excess of unemployment.

The price of something simply is the price of something and don’t ever forget it.

Tim Worstall, “Congratulations To Bolivarian Socialism – Finally A Sensible Economic Policy In Venezuela”, Forbes, 2016-10-15.

July 28, 2018

June 3, 2018

QotD: Price controls just make things more expensive in real terms

One of the perennial, and pernicious, political ideas is that if things are “too expensive” then we can fix that by just passing a law to make them less expensive. We see this just about everywhere and its sadly not limited to the more idiot sector of the left. Although of course it thrives there. Venezuela is a complete and total mess because Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro thought they would make life cheaper by limiting prices by law. Payday lending doesn’t exist in certain states because people like Elizabeth Warren insist that interest rates should not go “too high”. Those usury laws mean that interest rates are infinite – as the lending simply isn’t available at all. And yes, people over on the right have made the same sort of mistake – Nixon tried to fix gas prices after all.

Price fixing just always leads to things getting more expensive. As David Friedman explains:

The result – that price control results in a cost to the consumer, pecuniary plus nonpecuniary, higher than the uncontrolled price – does not depend on the details of the [supply and demand] diagram. Consumers cannot consume more gas than producers produce, so the nonpecuniary cost must be large enough to drive quantity demanded down to quantity supplied. Quantity supplied is lower than without price control, so cost to the consumer must be higher.

Tim Worstall, “Memo For Would Be Price Fixers – Price Controls Always Make Things More Expensive”, Forbes.com, 2016-08-16.

April 4, 2018

DicKtionary – I is for Investment – Gregor MacGregor

TimeGhost

Published on 3 Apr 2018I for investment, for financial success,

Or for a failure, cause it’s hard to guess,

But if there’s one man who could make you a beggar,

It’s today’s star, Gregor MacGregor.Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Written and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Based on a concept by Astrid Deinhard and Indy Neidell

Produced by: Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Camera by: Ryan Tebo

Edited by: Bastian BeißwengerA TimeGhost format produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH