Practical Engineering

Published 6 Aug 2020Exploring the complexities that go into the creation and application of asphalt concrete.

Use code80PRACTICALto get $80 off with purchase, including free shipping on your first box https://bit.ly/30sYo7c Go to HelloFresh.com for more details.Of all the ubiquitous things in our environment, roads are probably one of the least noticed. Our roads see tremendous volumes of traffic and withstand considerable variations in weather and climate, and they do it on a pretty tight budget. That’s really only possible because of all the scientists, engineers, contractors, and public works crews keeping up with this simple but incredible material called asphalt.

-Patreon: http://patreon.com/PracticalEngineering

-Website: http://practical.engineeringWriting/Editing/Production: Grady Hillhouse

Editing and Direction Help: Wesley CrumpThis video is sponsored by HelloFresh.

November 6, 2020

The World’s Most Recycled Material

September 17, 2020

Why Does Road Construction Take So Long?

Practical Engineering

Published 3 Jun 2020Explaining how earthwork works, and why road construction often takes so long.

Sign up for Brilliant for free at www.brilliant.org/PracticalEngineering and get 20% the annual premium subscription!

Like it or not, roads are part of the fabric of society. Travel is a fundamental part of life for nearly everyone. Unfortunately, that means road construction is too. But, I hope I can give you a little more appreciation for what’s going on behind the orange cones.

-Patreon: http://patreon.com/PracticalEngineering

-Website: http://practical.engineeringWriting/Editing/Production: Grady Hillhouse

Editing and Direction Help: Wesley CrumpThis video is sponsored by Brilliant.

September 14, 2020

QotD: Airportland

Most readers have spent time in Airportland. We know its particular wan light; the general flatness that makes the incline of jetways such a shock; its salty, sugary, and alcohol-infused cuisine; its detached social ambiance; its modes of travel (the long slog down the moving walkway, the hum of the people-moving carts, the standing-room-only shuttles, the escalators, the diddly-dup diddly-dup of roller bags, and — oh, yes — the airplanes); its fauna (emotional-support animals) and flora (plastic ficus); its mysterious system of governance; its language. Now and then, in Airportland, you spot a first-time visitor — confused by TSA rules, late for her flight, burdened by too many carry-ons. If you think the French are rude to those who don’t speak their language, you haven’t been paying attention in Airportland. We Airportlanders give these newbies no quarter. We sigh in exasperation as they’re sent back through security check for all the things they neglected to remove from their person. When they’re wandering Concourse E looking for their plane, because they thought they were in seat E68 (you know, like in a theater), when actually their flight leaves from B12 and their ticket class is E, we may take pity. But we hardly remember being that person, because once you’ve inhabited Airportland a handful of times, you’re a native.

And like native speakers, we don’t think much about the strange lingo we speak in Airportland. Take Gate. Some years ago, flying out of Peshawar, Pakistan, I passed through a dark set of catacombs inhabited by ruthless security guards and intelligence personnel with perhaps five checkpoints all lit by flickering overhead bulbs. Finally, like C.S. Lewis’s Lucy passing through the wardrobe into Narnia, I emerged into what I thought at first was a harshly lit bus station. It had the requisite faded plastic chairs and desultory counter offering stale packaged snacks and room-temperature soft drinks. Then I saw the sign over the doorway leading outside: GATE. I breathed a sigh of relief. Unlikely as it seemed, I had found my way to Airportland. But why Gate? Well, apparently there once was an actual gate, which stayed closed until the propellers of the plane were safely tied down and the passengers were free to pass through and board from the tarmac. (There were, of course, no “Jetways” — once a trademark, now generic — back in the day.)

Other terms of art abound in Airportland. Take concourse. It’s from the Latin, meaning “flowing together,” and outside Airportland it generally refers to an open area where passageways meet and people gather. In French, concours means “contest.” At the airport, the concourses are simply wide corridors, usually designated by letter, but if you like you can think of them as flowing, since they’re usually filled with a stream of humanity, and it often feels like a contest simply to reach the gate without incident.

Lucy Ferriss, “The Language of Airportland”, Lingua Franca, 2018-06-10.

July 10, 2020

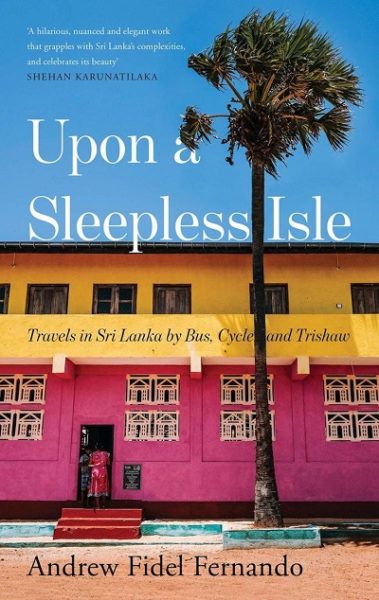

Upon a Sleepless Isle by Andrew Fidel Fernando

In The Critic, A.S.H. Smyth reviews this Gratiaen Prize-winning travel memoir of Sri Lanka:

Having returned to Sri Lanka from school and uni in New Zealand, and spent a few years consolidating a career in cricket journalism, AFF (as he is also known) decides to tour the country on a solo self-educational adventure – not least because big chunks of it were basically off-limits during his upbringing, thanks to the 26-year civil conflict with the LTTE/”Tamil Tigers”.

The book begins:

The smiles in Sri Lanka are as wide as the horizon, visitors say. The nation’s treasures are as boundless as the ocean, many report. But never let it be forgotten that the ineptitude of the government is as vast and as awesome as the heavens …

At this point, our intrepid would-be traveller just wants the ID card to which he, as a Sri Lankan citizen, is well entitled. But there follow six pages of brutal savaging of the bureaucracy (remember that bear scene in The Revenant …?), and then short treatises on social scandal, unsustainable development, the traffic, tourists, and the glossy travel magazines that bring them here. And we haven’t even left Colombo yet.

But he gets out and about soon enough, and in a punchy 240-page mildly-memoirish survey, utilising pretty much every form of transport barring the bullock cart, he sees the elephant herds at Minneriya, climbs the 1/8-Mile-High Club that was the rock fortress of Sigiriya, explores a highwayman’s hideout near Kandy, the surreal Lego-ish hill town of Nuwara Eliya, the tea estates, the ancient waterworks around Polonnaruwa, the temple-strewn Anuradhapura, the otherworldly Mannar island, the Southern beach towns, and on through the flattened LTTE heartlands up into Jaffna. (Cricket nerds, be advised: there is no cricket in this book.)

In all, his journey amounts to about seven or eight weeks on the road, and, Sri Lanka being a fairly small place, it’s worth noting that his is an entirely normal tourist itinerary – a visitor with even a mid-level budget and modest accommodation demands could cover all of it in a three-week holiday – just done more slowly and, crucially, with better local “access”, specifically linguistic.

Like all good “city-bred pansy” writer types, he gets into scrapes (a tuktuk crash), and makes a fool of himself (“helping” some fishermen), and the whole thing is narrated with much irreverent humour and ironic side-eye, topped off with a great line in exaggerated street-chat/aunty gossip and the occasional murderously-deft flick of the stiletto: “if you had the financial means to inspire a government worker out of apathy …” – all facets not exactly over-represented in Sri Lankan English letters (non-fiction, anyway. Novels are full of it).

Nor is his apparent economy dependent on foreknowledge on the reader’s part (aided certainly by the author’s more-or-less ingenuous exploratory conceit). Whatever learning AFF was already armed with here is lightly worn, he works in the historical and social context of each leg of the journey with a minimum of fuss (a certain journalistic pragmatism and efficiency paying off there, one assumes), and there’s really no time at which you feel he’s had to throw his bucket down the well of Wikipedia to get through to the end of a particular informative sub-section.

That said, considerable amounts of this material were new to me (which, in a whistlestop tour of the entire island, is not saying nothing). His trip to the abandoned rebel-descendant jungle village of Kumana is as intriguing as the details of the 1817 Uva rebellion are grim. And in particular, I’m grateful to him for introducing me to the life and works of the archaeologist John Still, and clueing me up as to the origin of the phrase “white elephant”: “after the Thai royal practice of presenting unpopular courtiers with tuskers that were ruinously expensive to maintain.”

Alas for AFF – the curse of writing first-draft history – Upon a Sleepless Isle also offers (or rather offered) two major hostages to fortune. Namely, his repeated and overt enthusiasm about the transition away from the family-oriented regime of Mahinda Rajapaksa (2005-15), and his vocal sympathy and support for Sri Lanka’s peaceful and tolerant Muslim minority. Only three months after the book was published, a series of domestic Muslim terrorist attacks took place around the country, killing hundreds, which in turn helped to usher in the present (Gotabaya) Rajapaksa government. These have aged almost so badly that it adds a certain piquancy to read his already-blasted hopes of just two years ago.

July 7, 2020

Taking stock after the worst of the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic

David Warren discusses an intractable “problem”:

I do not suppose it makes any practical difference what I have to say about a public health problem that invades the lives of billions; nor that readers will take me for a reliable epidemiologist when I say that the worst danger of that Batflu has now passed. (Infection rates spike, but the power of the virus to torture and kill has relented. The death rates continue downward.)

Nevertheless, I think there is some value in stating, even restating, the obvious — when what is obvious is in conflict with sensational reports, and the aggressive distortions of mass media, profiting from panic.

This Batflu became — more than any previous epidemic — a political issue, instantaneously. This is evident in the way it was spread, quite intentionally, by the Communist Party of China. (They shut down everything in Wuhan, except flights to Europe and America.) In all countries with democratic institutions, the disease became the centre of political attention, and unprecedented lockdowns were ordered. Likewise, unprecedented schemes of surveillance have significantly changed the relation between governments and governed, entirely for the worse. By means of current technology, the former will be able to perpetuate these changes, leaving those who wish to recover old liberties nowhere to hide.

Moreover, this is done by public demand. “The peeple” are easy to manipulate, once they have been frightened. The great majority of men, now and through the past, never cared about freedom. It has always been a minority concern, “for the intellectuals.” The “silent majority” will take their freedom, but only after their comfort and safety have been assured. The right to choose among consumer products is enough for them.

There are revolutions, such as the one that is now being attempted by the Left, but these never last. Either they are extinguished, under the wet blanket of public apathy, or the revolutionists succeed in installing a truly monstrous regime. Only thus, can they prolong their evil. Two generations of half-educated, indoctrinated, university grads favour a doctrinal dictatorship. Those still young are full of malign energy.

June 15, 2020

QotD: The very first “road trip”

Germany’s love for the automobile began with a road trip from nearby Mannheim to the town of Pforzheim, less than 30 miles from Stuttgart. In 1885, Karl Benz had invented his first Motorwagen, a three-wheeled vehicle with a gas-powered engine of his own design. One of the first times he managed to get it started, he drove it straight into his laboratory wall.

By 1888, he had a working prototype, which had successfully driven down a road. The now-patented Motorwagen had no gears and could not go up hills, but it worked. One morning, Benz’s wife Bertha decided to take the car on its first extended road trip. With her two sons, she pushed the car out of the garage, until it was far enough from the house that they could get it started without waking her husband.

Bertha Benz had a destination in mind — her parents’ house in Pforzheim, about 65 miles from her home. Following roads meant for wagons, she and her sons started the drive — the first recorded road trip in a car.

There were challenges. A pipe clogged; Benz cleaned it with her hat pin. A wire shorted; she insulated it with her garter. They needed more fuel; she convinced a pharmacist to sell her an unusually large amount of the gas the car used. When the brakes started wearing out, she had them shod with leather at a cobbler. When she reached a hill, she had the boys push (along with local help).

By the end of the day, the Benzes had reached Pforzheim, where Bertha telegraphed her husband that they were safe. After a few days’ visit, they drove back home to Mannheim.

Ten years ago, Germany created an official Bertha Benz Memorial Route, marking her historic road trip. Part of Bertha Benz’s motivation was to sell potential customers on the advantage of automobiles; although it took another decade or so, people eventually bought into this transportation revolution.

Sarah Laskow, “An 1888 Road Trip Sparked Germany’s Romance With Cars”, Atlas Obscura, 2018-02-28.

May 27, 2020

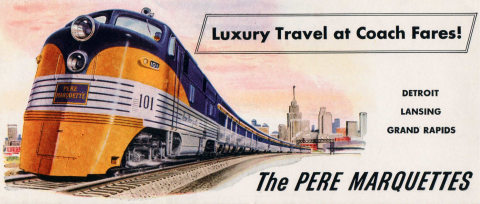

American passenger trains before Amtrak

George Hamlin reflects on the state of the US passenger rail system before the formation of Amtrak in 1971:

… non-commuter U.S. passenger trains can be said to have been under siege essentially for my entire lifetime, beginning not long after the end of World War II. Many railroads spent large sums to re-equip with streamlined lightweight equipment after the war, only to see what was originally couched as an investment turn into essentially a drain on their companies’ treasuries.

And the “rewards” for this? Passengers decamped to the rapidly-expanding airlines, and their personal automobiles. The decisive blow came in 1956, with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act, which led to the Interstate Highway System.

Quoting from Joe Welsh’s Pennsy Streamliners, The Blue Ribbon Fleet (page 138), “Referring to the challenge, [PRR President] Symes wrote ‘There is such a thing as planning an orderly retreat in the face of superior forces.’ Clearly, the bugle had been sounded.”

In 1958, an Interstate Commerce Commission Hearing Examiner predicted that there would be no intercity passenger trains by 1970; he only missed by four months, effectively (and didn’t count on the Southern Railway, Rio Grande and Rock Island shying away from the government’s largesse). In 1959, TRAINS magazine devoted an entire issue to what was now clearly a crisis; the cover bore the legend “Who Shot the Passenger Train?”, complete with simulated bullet hole.

The 1960s in the U.S. could well be described as the “train-off” decade from a transportation history perspective; get, and read, Fred Frailey’s Twilight of the Great Trains, for a blow-by-blow analysis. The 1970s quickly produced the Penn Central bankruptcy, which proved to be the catalyst for government intervention; less than a year later, Amtrak was on the scene.

And since, it has frequently found itself in a “Perils of Pauline” existence, ranging from lack of funding to buy equipment, in many cases, to several bouts of route eliminations, to micro-management by politicians that don’t seem to be willing to provide consistent operational funding so that the company can make reasonable plans.

May 15, 2020

Protecting the Innocent – Kids Evacuations – On the Homefront 003

World War Two

Published 14 May 2020The European powers may be at war but there’s now thing they can agree on: their young must be protected. So, before the first RAF or Luftwaffe bombs were even dropped on cities, countries are drawing up plans to save as many lives of their youth as they possibly can.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_t…

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Anna Deinhard

Written by: Isabel Wilson and Spartacus Olsson

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Isabel Wilson

Edited by: Mikołaj Cackowski

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Sources:

USHMM

Bundesarchiv

IWM LN 6194, HU 36871, D 2238, D 10457, D 2592, D 5081, D 24903, IWM D 15530, D 2045, HU 3323, Art.IWM PST 3095, Art.IWM PST 13854, Art.IWM PST 15100, D 9211, D 824, D 257, D 5665, D 2224, D 1939A, F 4422

Portrait of John Anderson, courtesy Yousuf Karsh, Dutch National Archives

from the Noun Project: students by Piotrek Chuchla, mother by Mr. Minuvi, Pregnant by Wojciech Zasina, bag by Nabilauzwa, Gas Mask by Nico Ilk from the Noun Project, Underwear by The Icon Z, baby clothes by Llisole, espadrilles shoes by Edwin PM, socks by Анна Пасечная, Toothbrush by amantaka, Comb by Randall Barriga, towel by Pixelz Studio, handkerchief by Vectors Market, soap by Jae Deasigner, coat by Ilham Juliandi, Food by Atif ArshadSoundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”

Johannes Bornlof – “The Inspector 4”

Johannes Bornlof – “Deviation In Time”

Farell Wooten – “Blunt Object”

Jo Wandrini – “Puzzle Of Complexity”

Gavin Luke – “Drifting Emotions 3”

Howard Harper-Barnes – “Prescient”

Fabien Tell – “Last Point of Safe Return”

Andreas Jamsheree – “Guilty Shadows 4”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

5 hours ago (edited)

Welcome back to another episode of On the Homefront! Researching this episode about evacuations was a fun one to dive to because in the UK, we learn about about children evacuees during the war but of course what we’re not taught is the mass scale of this operation. For each of the millions of children displaced during the war, they each came away with it with their own story and I hope I’ve captured that here. Looking forward to reading your comments! Be sure to follow us over on instagram at https://www.instagram.com/world_war_two_realtime/ and let us know what other aspects of life on the homefront you’d like to hear about!Cheers,

Izzy

May 11, 2020

“I’m so old, I don’t even buy green bananas anymore”

While I’m not quite at Kim du Toit‘s advanced age, I have had a few intimations of mortality over the last few years that do force a certain amount of introspection:

The other day I made reference to the fact that I would be unlikely to be flying anywhere in 2020, and might only do so in late 2021 — and for the first time in my life, I said to myself, “… should I live that long.”

I think the most depressing thing about getting old is that you get wary of making long-term plans — the old joke “I’m so old, I don’t even buy green bananas anymore” is a perfect example — and it can be depressing.

It doesn’t have to be, of course. A friend of my own vintage recently embarked on a business venture which involves a massive construction project, and when I asked him when the whole thing will be finished, he said airily, “About fifteen or twenty years’ time.” If that is true, he would be around eighty years old at completion date.

I’m not sure I would do anything like that. At the same time, I’m still buying green bananas, so to speak, so there’s that.

At some point in a person’s life, you become resigned to the fact that you’ll never climb Everest, or race at Monaco, or make a billion dollars, or sleep with some famous beauty (maybe because she just died). Those are the big dreams, of course, and mostly — realistically, even — just pipe dreams. Still, their disappearance is a little of a jolt; which is probably a preparation for a much bigger disappointment when you realize that your age precludes you from doing something that you did only little while ago. As an example, I’m most likely never going to be able to go deer-stalking in Scotland with Mr. Free Market, Doc Russia and Combat Controller again, because the trudging over the uneven ground of the Cairngorm Mountains is, to put it mildly, unthinkable. I made a joke about that with the guys during a telemeeting, the other day, and said that if I were to do it again, I would only ever shoot at a distance no further than 50 yards away from the Land Rover — i.e. close to the road — whereupon Mr. Free Market said bluntly, “Then you’re never going to take another shot” (because most of the stalks now involve a prospect of a mile or two’s scrambling before the deer even come within a respectable shooting distance, assuming they haven’t moved in the interim).

So goodbye to all that, then.

It’s even more poignant when you think of your approaching end with regards to family and friends, especially family. New Wife’s elder son has given her a grandson; my own kids’ prospect of doing the same is becoming more and more remote with each year. That, actually, doesn’t bother me too much as I’ve never been one of those parents who pushes their kids to provide grandchildren — in fact, I specifically told mine that I would never push them that way, and I’ve kept my promise. But it also means that I’ll never be able to do the grandfather things with grandsons that my own grandpa did with me, and that’s a little sad.

March 9, 2020

One of the economic effects of the Coronavirus outbreak might actually be bottom-line positive

Tim Worstall explains:

“Trade Show Portfolio – Guy Lewis Photography” by Guy Lewis is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

One notable thing about tech events is that they tend to be in interesting places like Amsterdam and Barcelona, and you don’t get many self-employed attending. Because someone self-employed loses days of paid hours, has to pay for the flights and the tickets. And they can get the same stuff from YouTube or various learning sites like Lynda.com. Tech events are mostly a jolly for employees in bloated companies. You get 3 days out of the office, have some fun and the boss picks up the tab. Losing this will probably improve the bottom line. And “business conferences” are mostly the same.

For people working more from home, that’s a good thing. Reduced travel costs (time and petrol), less tiredness. This is gradually happening anyway, but Coronavirus has given it a boost.

And maybe everyone realises that a system of education inherited from the time before Gutenberg, when books were a scarce resource, is perhaps in need of reform. OK, you probably need to be at a university for cutting up cadavers in medicine, but for history or computer science you can probably do most of it from your parent’s spare room.

One thing about the way people work is that they often fall into habits. Change often comes from startups and small businesses because they don’t have habits. Sometimes, they’re even anti-habit. Someone in a large company sees something as wasteful and scraps it in the new company. Microsoft let their people wear what they wanted for work, rather than suits. And gradually, those new businesses replace the old. But there’s also sometimes crises that break habits. Someone is forced to do something and gets their eyes opened. They perhaps realise that the alternative works fine, or maybe better.

February 27, 2020

QotD: Clichés of bad travel writing

The poor-but-oh-so-happy sentiment pops up without fail in any crappy travel magazine version of a visit to Myanmar, Laos, or Nepal (and probably any other desperately poor and badly governed country), in which “the people” are always gleeful, generous, and colorful. I’m not exactly sure what it is about being ruled by insane dictators that makes people so damn nice, but here’s an idea: If you’re a Western travel writer, or, say, German tourist, and you’re going to an impoverished country full of hungry people in which you clearly stand out as someone with money to spend, people might be extra nice to you.

Kerry Howley, “But the People Are So Friendly“, Hit and Run, 2005-08-18.

February 26, 2020

“… the First World’s most dysfunctional train: The Canadian, which in theory links Vancouver to Toronto”

Chris Selley fires all his guns at the pride of VIA Rail Canada’s passenger services, The Canadian:

With the Ontario Provincial Police somehow finally roused to action in Tyendinaga, Ont., it seems the CN railway blockade may not last its third week. This outstanding achievement in law enforcement will come as a relief in particular to the nation’s business community, people who enjoy staple foods, and the propane-dependent. The minority of travellers along the Windsor-to-Quebec City corridor who ride VIA Rail were not as imperilled: most essential, tight-budgeted VIA trips can also be made by bus, with only moderate time lost and with money saved as a consolation. But they too will be pleased. As maddening as VIA’s corridor services can be, with their ancient rolling stock, outrageously stale food, mostly theoretical wi-fi, schedules that get slower rather than faster and reliable delays regardless, trains are just genetically superior to buses.

Or at least, most are. The Windsor-to-Quebec City services are practically Japanese in comparison to what must be the First World’s most dysfunctional train: The Canadian, which in theory links Vancouver to Toronto. It has been shut down almost since the blockade began, and hardly anyone has noticed. It’s time we talk about this crazy thing.

What, you may ask, is the most ridiculous thing about The Canadian? Some might point to the astonishing level of subsidy: In 2018, the average corridor passenger enjoyed a subsidy of $32, or 17 cents per mile. The average passenger on The Canadian: $596, or 48 cents a mile, for a total of $49 million.

But never mind the price for a second; look what it’s buying. Fifty years ago, CN’s Super Continental was scheduled to take 67 hours. Today The Canadian, plying the same route and giving way to every freight train, is budgeted a mind-boggling 85 hours eastbound and 97 westbound.

[…]

For all the subsidies, The Canadian is eye-wateringly expensive. For the full one-way trip, a cabin for two will set you back $3,824, meals included. You can take a five-day mid-range Caribbean cruise for that, and that’s no coincidence: The Canadian is essentially a cruise ship on rails. It’s just that, well, Canadian taxpayers don’t subsidize cruise lines. Because that would be nuts.

I’ve always wanted to ride The Canadian, but I never could afford both the time and the money at the same time. (I have the time now, but I’m struggling to pay my bills, so even a GO Train trip into Toronto needs to be carefully budgeted … a trip on The Canadian would be a very significant percentage of my gross annual income!).

January 19, 2020

January 1, 2020

The Day The Gauge Changed

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 16 Jun 2018The History Guy remembers the 1886 Southern Railroad Gauge Change, an important moment in railroad history.

The photographs used in the episode are Public Domain images from the age of steam. As photos of actual events are sometimes not available, I will often use photographs of similar events and objects for illustration.

The economic analysis mentioned in the episode is available here: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/ite…

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: Five Minutes of History is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

https://teespring.com/stores/the-hist…The episode is intended for educational purposes. All events are presented in historical context.

#railroad #ushistory #thehistoryguy

December 28, 2019

American railways are simultaneously world-beating and terrible

That’s because, as Sean Smith and Peter Earle point out, there are two very different entities running on America’s rails:

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) locomotive 5399, Kansas City Southern (KCS) 4807, and 1890 westbound on the BNSF Emporia Sub near Timberland Blvd West of Northgate Street in Olathe, Kansas.

Photo by Tyler Silvest via Wikimedia Commons.

American railways are the envy of the world.

Many might shake a collective head at that statement. In the case of passenger rail that is an appropriate reaction. Since it was pieced together – a government-constructed Franken-rail system built of numerous bankrupt railways which were essentially nationalized – Amtrak has been a reliable money sink, losing tens of billions of dollars since 1970.

Any traveler that has used Amtrak to any significant extent has firsthand experience with the crumbling infrastructure, frequent delays, and general unpleasantness that accompanies U.S. passenger rail service. Even the oft-cited bright spot of Amtrak, the “high speed” Acela system (which shuttles between Boston and Washington D.C) pales in comparison when compared to high-end passenger rail systems in Western Europe, Japan, and China.

Bullet trains routinely travel at least 200 mph, whereas Acela trundles along at a pedestrian 84 mph, and there is no indication (and probably no intention) of that gap closing anytime soon.

U.S. passenger rail services in general are money-losing and antiquated versus their global counterparts, an inarguable (and to public transport proponents, embarrassing) fact. Passenger rail is just one part of the story, and serves as an excellent example of how not to manage a rail system. In fairness, efforts to turn Amtrak around (mainly through aggressive cost cutting) do seem to be having an impact, as current year losses total a shade under $30 million. It’s an admirable effort to be sure, but decades of losses, poor service, and general mismanagement cannot be ignored.

The U.S. freight railway system, conversely, is the envy of the world, and this is not hyperbole or chest thumping; the facts back it up. Since the Staggers Act of 1980, which deregulated freight rail, improvements have been substantial. U.S. freight railways carry 81% more ton-miles of freight, and costs have fallen 46%. (It isn’t common for an industry to increase its capacity by 81% while reducing costs by nearly half.) That level of success has even been noted by the Community of European Railway and Infrastructure Companies, which might be surprising, given the common assumption that Europe has a monopoly on rail excellence.

Compared side by side, it seems a conundrum: Amtrak limps along, still relying upon billions of dollars worth of taxpayer-financed subsidies, while U.S. freight railways evince growing profitability and capacity amid rapidly falling costs. Why are U.S. freight rails so profitable when U.S. passenger rail – sometimes traveling the same routes, on some of the same rails – remains a perennial money pit?