Bee Here Now

Published 23 Oct 2023The Stockton-Darlington Railway wasn’t the first time steam locomotives had been used to pull people, but it was the first time they had been used to pull passengers over any distance worth talking about. In 1825 that day came when a line running all the way from the coal pits in the hills around County Durham to the River Tees at Stockton was opened officially. This was an experiment, a practice, a great endeavour by local businessmen and engineers, such as the famous George Stephenson, who astounded crowds of onlookers with the introduction of Locomotion 1 halfway along the line, which began pulling people towards Darlington and then the docks at Stockton.

This was a day that would not only transform human transportation forever, but accelerate the industrial revolution to a blistering pace.

In this video I want to look at what remains of that line — not the bit still in use between the two towns, but the bit out in the coalfields. And I want to see how those early trailblazers tackled the rolling hills, with horses and stationary steam engines to create a true amalgamation of old-world and new-world technologies.

(more…)

February 16, 2024

What remains of the “first” steam powered passenger railway line?

December 19, 2023

Overthinking Thomas the Tank Engine: What Actually Is Thomas?

Jago Hazzard

Published 13 Aug 2023Peep peep!

(more…)

December 10, 2023

The history of the steam engine … but interactive

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes is pleased to announce the release of a new ongoing project to illustrate the steam engine in an interactive format:

I’m excited to announce something I’ve been quietly working on for a few months now behind the scenes. Some of you may be familiar with the explorable interactive articles of Bartosz Ciechanowski. They are so clearly written and so cleverly explorable, that they give an intuitive grasp of how many very complicated technologies work. My favourite is his article on mechanical watches. Be warned: if you’ve not seen these before, you’re about to lose a good few hours.

But his article on watches — which came out just as I was doing some research on the development of watches, and which proved an invaluable reference work — got me thinking about how great it would be to have something similar not just for how current technologies function, but to show how they changed over time. Wouldn’t it be great, I dreamed, to have a similarly intuitive way to explore and appreciate the process of improvement. And to correct lots of misapprehensions about the development of various technologies along the way.

As it turned out, my fellow inventions history fanatic Jason Crawford, who runs the non-profit The Roots of Progress, had been thinking along the same lines. (Drumroll starts softly.) So with the help of the Matt Brown we’ve been able to realise what is hopefully just the first small step of our vision. (Drumroll intensifies.) Based on my recent work re-writing the standard pre-history of the steam engine (drumroll crescendoes), allow me to present:

(Cue trumpets!)

The interactive, animated, **Origins of the Steam Engine**

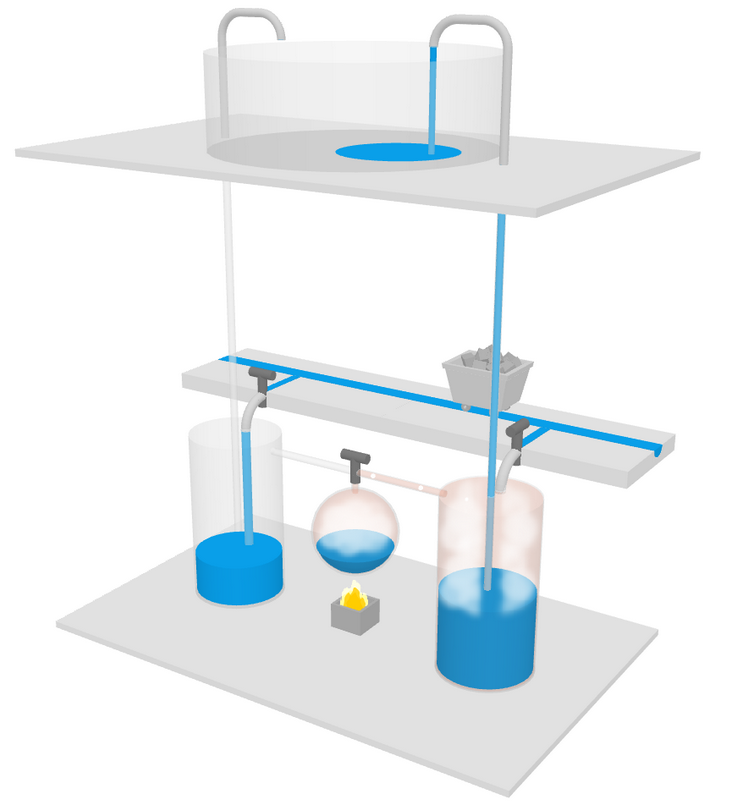

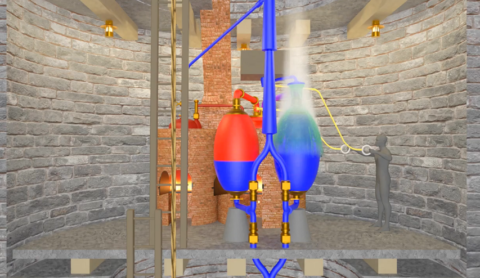

Alongside contemporary illustrations of the many devices, you can play around with the animated models, dragging them to see them from different angles. It introduces what are so far the only interactive and animated models yet made of a great many devices — from Philo of Byzantium’s 3rd Century BC experiments, to Salomon de Caus’s 1610s solar-activated and self-replenishing fountains and musical instruments, and the 1606 steam engine of the Spanish engineer Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont:

It also contains the first depictions of the 1630s and 40s devices of Kaspar Kalthoff and William Petty. These are the experiments I discovered about a year ago, which I hope will now be given a place in the canon of the history of the steam engine. (You can read my discussion of the evidence I’d stumbled across about them here.)

November 15, 2023

The Future of Railways (circa 1961)

Jago Hazzard

Published 26 Jul 2023The future is slightly dingy.

(more…)

October 26, 2023

Look at Life – Draw the Fires (1963)

PauliosVids

Published 21 Nov 2018The railways are changing, with coal-powered steam being phased out and replaced by diesel engines by 1972. Crowds pay their respects to the Flying Scotsman‘s last departure from Kings Cross as it is replaced by a 3,300-horsepower diesel. The network is being modernised by new signalling, longer continuous track on concrete sleepers and flyovers, and controversial closures of lines.

July 25, 2023

WWI Footage: Narrow Gauge Train Lines in France

Charlie Dean Archives

Published 14 Aug 2013American forces constructing railways throughout France to help move men and supplies during World War One. We see US Army personnel laying the sleepers and track for the extensive network of two foot (60cm) narrow gauge lines, ballasting work, loading and laying of pre-built trackwork. We also see scenes of the railway in action as the little trains trundle along country lanes and through the town streets. The film ends with scenes of the train taking soldiers towards the front lines.

After the war the lines were abandoned and most of the locomotives and rollingstock simply left where they were last used, with many being salvaged by the locals to help with logging activities.

CharlieDeanArchives – Archive footage from the 20th century making history come alive!

June 11, 2023

Rewriting the well-worn story of how the steam engine was invented

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes pushes back against the story we’ve been telling for over 200 years about how the steam engine came to be:

The standard pre-history of the steam engine goes a little like this:

- There were a few basic steam-using devices designed by the ancients, like Hero of Alexandria’s spinning aeolipile, which are often regarded as essentially toys.

- Fast forward to the 1640s and Evangelista Torricelli, one of Galileo’s disciples, demonstrates that vacuums are possible and the atmosphere has a weight.

- The city leader of Magdeburg, Otto von Guericke, c.1650 creates vacuums using a mechanical air pump, and is soon using atmospheric pressure to lift extraordinary weights. This sets off a spate of experimentation by the likes of Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens, and Denis Papin, to create vacuums under pistons.

- As a result of the new science of vacuums, by the 1690s and 1700s the mysterious Thomas Savery and especially the Devon-based ironmonger Thomas Newcomen are able to develop the first commercially practical engines using atmospheric pressure. Steam engine development continued from there.

This is the narrative that had become set in the 1820s, if not earlier, and has been repeated with many of the same names and dates by book after book after book ever since. It’s a narrative that I have even repeated myself.

But, as I only recently discovered, atmospheric pressure and vacuums were actually being exploited long before Torricelli was even born, by people who believed that vacuums were impossible and had no concept of atmospheric pressure. Devices very much like Savery’s, which exploited both the pushing force of expanding hot steam and the sucking effect of condensing it with cold — what we now know to be caused by atmospheric pressure — were being developed far earlier.

I began to give a more accurate account of the development of the atmospheric engine in a detailed three-part series on why the steam engine wasn’t invented earlier (see parts I, II, III, which give more detail and the references). But I haven’t put it all together in one easily digestible place, and since writing I’ve continued to discover even more. So here’s a rough sketch summarising what really happened, based on everything I’ve found so far […]

The development of the atmospheric engine was thus significantly longer and more complicated than the traditional narrative suggests. Far from being an invention that appeared from out of the blue, unlocked by the latest scientific advancements, it started to take shape from decades and centuries of experiments and marginal improvements from a whole host of inventors, active in many different countries. It’s a pattern that I’ve seen again and again and again: if an invention appears to be from out of the blue, chances are that you just haven’t seen the full story. Progress does not come in leaps. It is the product of dozens or even hundreds of accumulated, marginal steps.

May 6, 2023

Coronation Weekend

Jago Hazzard

Published 5 May 2023For us train nerds, “Coronation” means something very different.

April 22, 2023

The Big Four

Jago Hazzard

Published 1 Jan 2023It’s 100 years since the Grouping – what happened, why and how?

(more…)

April 12, 2023

Miniature Railway (1959)

British Pathé

Published 13 Apr 2014Romney, Kent.

L/S of a lovely looking train locomotive. A man stands next to it and one realises how small the train is. It is one third of an ordinary train size — says voiceover. However, this is not a toy but a regular public railway, smallest in the world. It is officially known as the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, it runs between Romney and Dungeness and its passengers are children. This tiny railway must conform to the same Ministry of Transport regulations as any other trains. M/S of a driver Mr Bill Hart, checking the train. C/U shot of a plaque reading “Winston Churchill”. This is the engine’s name. Several shots of Mr Hart checking the train. Mr Hart enters his cabin and starts shovelling coal into the boiler. C/U shot of the coal being thrown in and a little door closed. This train takes one third of the coal needed for a regular size train. The train starts moving.

L/S of the two men turning locomotive on turntable to place it on rails. M/S of a woman cleaning windows along the train. Children arrive and station master, Reg Marsh, directs them to their coaches. M/S of the group of girls entering the train. M/S of the station master Mr Marsh blowing a whistle as a sign that train leaves the station. M/S of an elderly man looking at a huge pocket watch on a chain, and afterwards, in direction of the train. He is Captain Howey, a man responsible for having the line built. C/U shot of the watch — Roman numerals. M/S of Mr Howey as he puts the watch in his pocket. C/U shot of Mr Howey’s face.

M/S of the little train moving. C/U shot of its little chimney with a smoke coming out. M/S of the Rose family from Sanderstead, Surrey with their dog Trixie enjoying the ride C/U shot of driver’s face with the smoke covering it up to the point it becomes invisible. Another little train passes it going in different direction. Several shots of the two little trains moving. A car stops to wait for the train to pass. L/S of the little train as it approaches the station.

Note: Another driver appearing in the film is Peter Catt. Combined print for this story is missing.

(more…)

April 4, 2023

When the steam engine itself was an “intangible”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the steam engine patent of James Watt didn’t immediately lead to Watt and his partner Matthew Boulton building a factory to create physical engines:

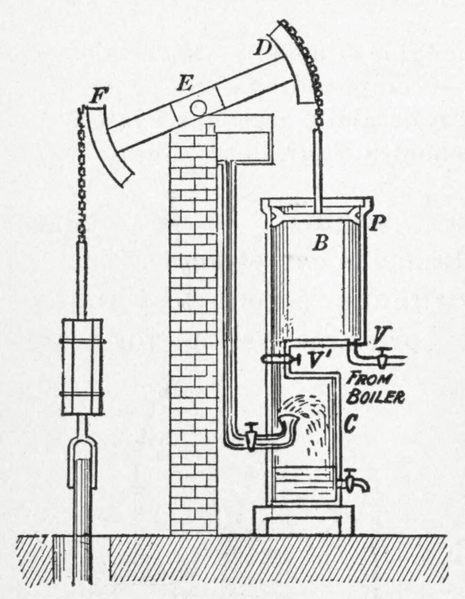

Diagram of a Watt steam engine from Practical physics for secondary schools (1913).

Wikimedia Commons.

… one of the most famous business partnerships of the British Industrial Revolution — that between Matthew Boulton and James Watt from 1775 — was originally almost entirely based on intangibles.

That probably sounds surprising. James Watt — a Scottish scientific instrument-maker, chemist and civil engineer — became most famous for his improvements to the steam engine, an almost archetypal example of physical capital. In the late 1760s he radically improved the fuel efficiency of the older Newcomen engine, and then developed ways to regulate the motions of its piston — traditionally applied only to pumping water — so that it could be suitable for directly driving machinery (I’ll write more on the invention itself soon). His partnership with Matthew Boulton, a Birmingham manufacturer of buttons, candlesticks, metal buckles and the like — then called “toys” — was also based from a large, physical site full of specialised machinery: the Soho Manufactory. On the face of it, these machines and factories all sound very traditionally tangible.

But the Soho Manufactory was largely devoted to Boulton’s other, older, and ongoing businesses, and it was only much later — over twenty years after Boulton and Watt formally became partners — that they established the Soho Foundry to manufacture the improved engines themselves. The establishment of the Soho Foundry heralded James Watt’s effective retirement, with the management of this more tangible concern largely passing to his and Boulton’s sons. And when Watt retired formally, in 1800, this coincided with the full depreciation of the intangible asset upon which he and Boulton had built their business: his patent.

Watt had first patented his improvements to the steam engine in 1769, giving him a 14-year window in which to exploit them without any legal competition. But his financial backer, John Roebuck, who had a two-thirds share in the patent, was bankrupted by his other business interests and struggled to support the engine’s development. Watt thus spent the first few years of his patent monopoly as a consultant on various civil engineering projects — canals, docks, harbours, and town water supplies — in order to make ends meet. The situation gave him little time, capital, or opportunity to exploit his steam engine patent until Roebuck was eventually persuaded to sell his two-thirds share to Matthew Boulton. With just eight years left on the patent, and having already wasted six, Boulton and Watt lobbied Parliament to grant them an extension that would allow them to bring their improvements into full use. In 1775 Watt’s patent was extended by Parliament for a further twenty-five years, to last until 1800. It was upon this unusually extended patent that they then built their unusually and explicitly intangible business.

How was it intangible? As Boulton and Watt put it themselves, “we only sell the licence for erecting our engines, and the purchaser of such licence erects his engine at his own expence”. This was their standard response to potential customers asking how much they would charge for an engine with a piston cylinder of particular dimensions. The answer was, essentially, that they didn’t actually sell physical steam engines at all, so there was no way of estimating a comparable figure. Instead, they sold licences to the improvements on a case-by-case basis — “we make an agreement for each engine distinctly” — by first working out how much fuel a standard, old-style Newcomen engine would require when put to use in that place and context, and then charging only a third of the saving in fuel that Watt’s improvements would provide. “The sum therefore to be paid during the working of any engine is not to be determined by the diameter of the cylinder, but by the quantity of coals saved and by the price of coals at the place where the engine is erected.” They fitted the licensed engines with meters to see how many times they had been used, sending agents to read the meters and collect their royalties every month or year, depending on the location.

This method of charging worked well for refitting existing Newcomen engines with Watt’s improvements — in those cases the savings would be obvious. It also meant that Boulton and Watt incentivised themselves to expand the total market for steam engines. The older Newcomen engines were mainly used for pumping water out of coal mines, where the coal to run them was at its cheapest. It was one of the few places where Newcomen engines were cost-effective. But for Watt and Boulton it was at the places where coals were most expensive, and where their improvements could thus make the largest fuel savings, that they could charge the highest royalties. As Boulton wrote to Watt in 1776, the licensing of an engine for the coal mine of one Sir Archibald Hope “will not be worth your attention as his coals are so very cheap”. It was instead at the copper and tin mines of Cornwall, where coal was often expensive, having to be transported from Wales, that the royalties would be the most profitable. As Watt put it to an old mentor of his in 1778, “our affairs in other parts of England go on very well but no part can or will pay us so well as Cornwall”.

February 28, 2023

The strange Steam Locomotive that was built like a Diesel – SR Leader Class

Train of Thought

Published 4 Nov 2022In today’s video, we take a look at the Southern Railway “Leader” locomotive that was built like a diesel, powered by steam and had a lot pros and cons.

(more…)

December 20, 2022

The forgotten Thomas Savery

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes remembers the work of inventor Thomas Savery:

Screenshot from “Savery’s Miners Friend – 1698”, a YouTube video by Guy Janssen (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dt5VvrEIj8w)

We know surprisingly little about Thomas Savery — the inventor of the first widely-used steam engine. Unfortunately, his achievements were almost immediately overshadowed by the engine of Thomas Newcomen, and so he’s often only mentioned as a sort of afterthought — a loose and rather odd-seeming pebble before the firmer stepping stones of Newcomen, Watt, Trevithick, and other steam engine pioneers in the standard and simple narratives of technological progress that people like to tell. I’ve often seen Savery’s name omitted entirely.

He is even neglected by the experts. The Newcomen Society, of which I am a new member, has an excellent journal — it is the best place to find scholarly detail about all steam pioneers, and about the history of engineering in general. Yet even it only mentions Savery in passing. In over a century, Savery has been named in the titles of just three of its articles, and the last was published in 1986.

I think Savery is extremely under-rated, and deserves to be studied more. Fortunately, we do know quite a bit about the engine he designed, which he intended primarily for raising the water out of mines. Steam was admitted into a chamber, and then sprayed with cold water to condense it. This caused mine water to be sucked up a pipe beneath it, by creating a partial vacuum within the chamber and thus exploiting the relative pressure of the atmosphere on the surface of the mine water. Then, hot steam was readmitted to the chamber, this time pushing the raised water further up through another pipe above. Two chambers, the one sucking while the other pushed, created a continuous flow. (Video here.) We have dozens of images and technical descriptions of Savery’s engine, as it continued to be used for decades, especially in continental Europe.

But we know essentially nothing about Savery’s background, training, inspiration, or profession, and most of the supposedly known biographical details we have for him are simply wrong. There is no evidence that he was a “military engineer” or a “trenchmaster”, for example — mere speculation that has been repeated so often as to take on the appearance of fact. Savery simply appears out of nowhere in the 1690s, with his inventions almost fully formed.

Yet in Savery’s own writings we can see a few tantalising hints of how he thought, including some flashes of brilliance. I kept coming across them by chance, when investigating various energy-related themes with Carbon Upcycling. Take the following aside, from Savery’s 1702 prospectus for his steam engine: “I have only this to urge, that water in its fall from any determinate height, has simply a force answerable and equal to the force that raises it”. Savery here seems to be hinting at some idea of the conservation of energy, and perhaps of a theoretical maximum efficiency — in a phrase that is remarkably similar to that used by the pioneers of water wheel theory half a century later, and to Sadi Carnot when he applied the same ideas to early thermodynamics.

Savery, frustratingly, doesn’t expand any further on the point, except to then casually mention the notions of both mechanical work and horsepower — over eighty years before James Watt. Savery noted that when an engine will raise as much water as two horses can in the same time, “then I say, such an engine will do the work or labour of ten or twelve horses” — ten horsepower, rather than two, because you’d need a much larger team of horses from which to rotate fresh ones while the others rested, to keep raising water as continuously as the force of a stream could turn a water-wheel, or his steam engine could pump. (Incidentally, Watt wasn’t even the second person to use horsepower — the same concept was also mentioned by John Theophilus Desaguliers in the 1720s and John Smeaton in the 1770s. Watt just managed to get all the credit later on. Perhaps watts should really be called saveries, even if he was less precise.)

September 13, 2022

Down the Line – A look into the legacy of the cuts made to the rail network by Doctor Beeching (2008)

Kevin Birch

Published 29 Jul 2013Joe Crowley meets the people who battled to save their local railway lines in the South of England in the 1960’s.

First aired on BBC One 26th October 2008

September 6, 2022

Scotland’s AMAZING Jacobite Steam Train

Dylan’s Travel Reports

Published 4 Dec 2020An amazing day out on West Coast Railways’ iconic Jacobite steam train from Fort William to Mallaig and back, part of the stunning West Highland Line!

Date of Travel: 21 October 2020

Class of Travel: First Class

Rolling Stock: LMS Stanier Class 5 4-6-0/Mk1

Cost of Ticket: £133.75 ($176.10, €150; price for 2 people)

Origin: Fort William, United Kingdom (Scotland)

Destination: Mallaig, United Kingdom (Scotland)

*Currency conversions correct as of 09/11/2020 to nearest $/€0.05

(more…)